The public has, rightly, lost faith in politicians, experts and the media. Progress seems impossible in politics or culture. Massive impersonal bureaucracies, the beguilements of the capitalist market, and ideologies propounded by parties, intellectuals and institutions fill us with disorienting clichés and false identities. We are unable to discern the truth, communicate it effectively to each other, or find an authentic role through which to connect with others and escape the forces that divert our potential for genuine action into unthinking conformity or delusional grandstanding.

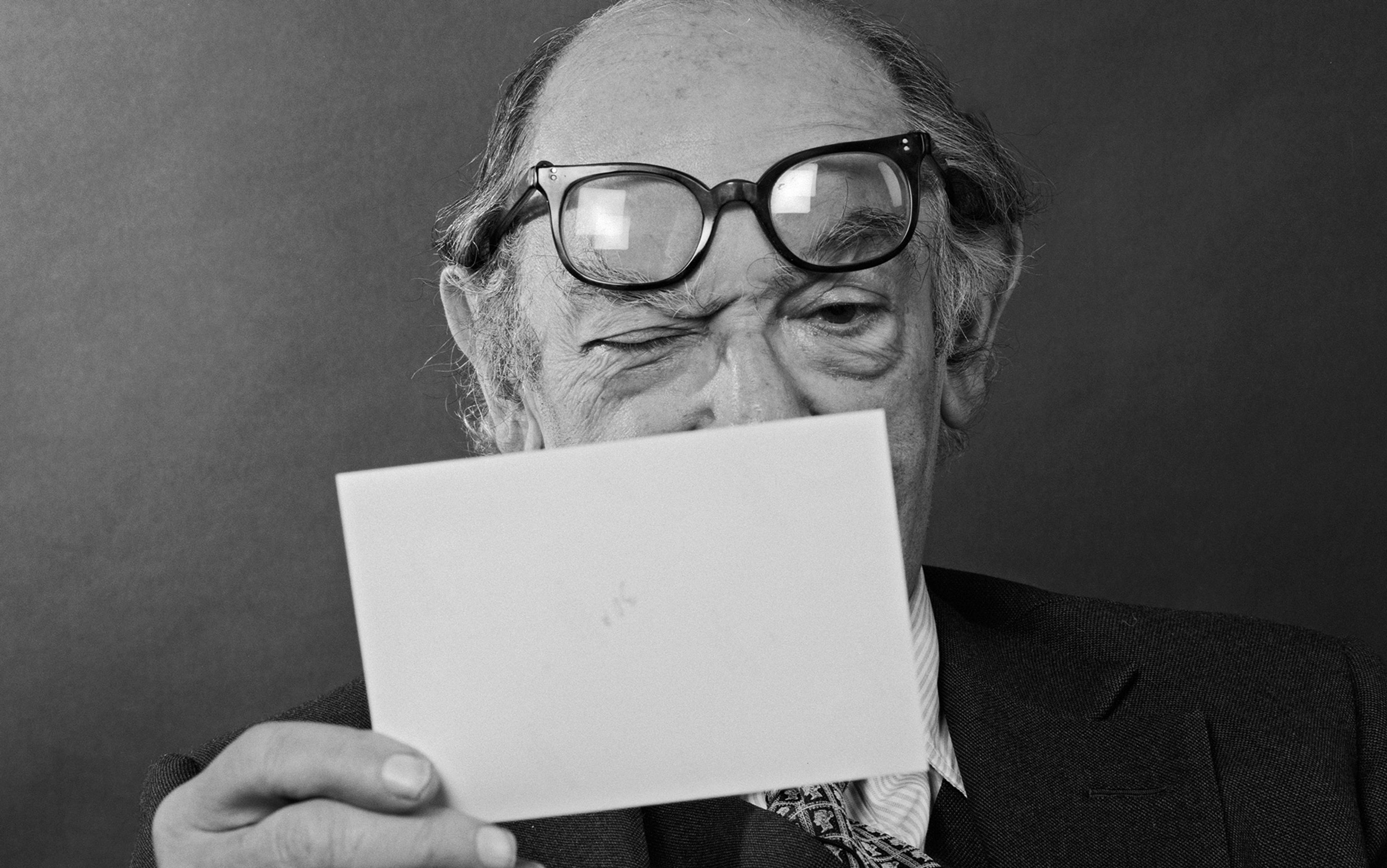

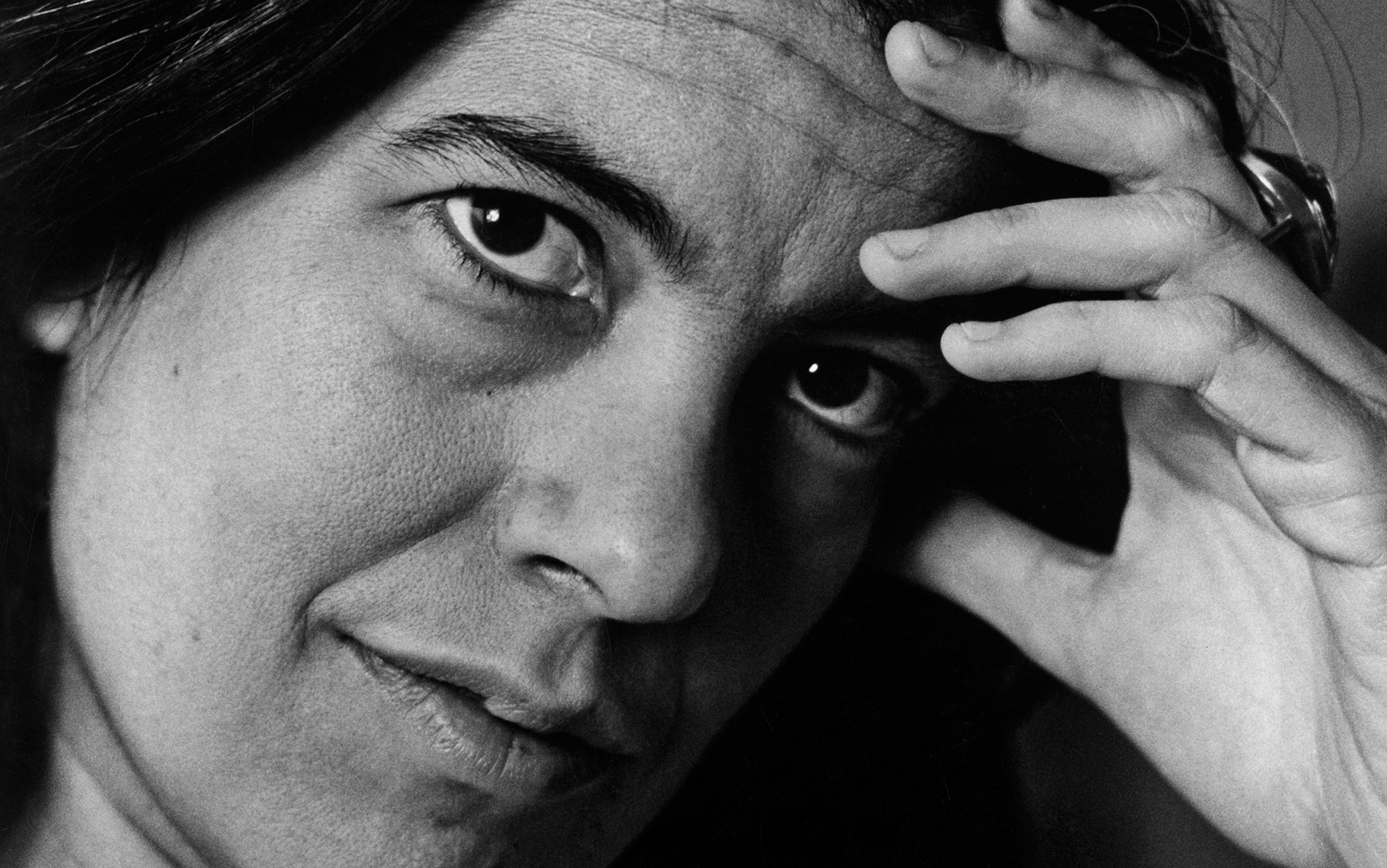

So argued, from the crisis of the Second World War until their deaths in the 1970s, two of the most important intellectuals of the midcentury United States: Harold Rosenberg and Hannah Arendt. Close friends for nearly three decades, their relationship inspired their intertwined theories of action and judgment, and their shared turn towards the role of cultural critic for a mass public. However, while Arendt is now seen as a central figure in the modern philosophical canon, Rosenberg has been all but forgotten, as has the critical dialogue between them.

Rosenberg was one of the leading American thinkers about art in the years after the Second World War, when the US replaced Europe as the centre of the art world. Thanks in part to his critical essays, artists like Barnett Newman, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock entered art history, and made modern art seem synonymous with US culture. He also influenced, and was influenced by, Arendt, with whom he became friends in the late 1940s. The two developed a set of ideas about how what they called ‘action’ connected aesthetics and politics. Over the following two decades, they continued rethinking the meaning of action as they both taught on the Committee on Social Thought programme at the University of Chicago.

In the four decades after his death, Rosenberg has faded into poorly remembered caricature. His distinctive ideas of action – non-systematic, always evolving, and elaborated in essays gathered in collections out of print since the 1980s – have been dismissed by art historians like Michael Fried, Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster as ‘half-romantic, half-petty-bourgeois’ and ‘a psychologising whine’, as Christa Noel Robbins puts it in Artist as Author (2021). While these scholars are wrong to write off Rosenberg, they are right to find in him an enemy of the kind of criticism they practise. His essays bristle with provocative critiques of how academics, museum professionals, gallerists and art critics reduce works of art into instruments of pedagogy or profit-making, diverting attention away from the real stakes of making art.

The artists about whom Rosenberg wrote were people he understood to be struggling to create a human life for themselves amid capitalism’s oppressions and illusions. In doing so, he argued, they broke with the conventions of art history. The production of beautiful objects, membership in a self-conscious avant-garde, the representation of politically useful subject matter and even the pursuit of originality fell away as they strove no longer to make art, but to act, whether on canvas, in sculpture or through the responses their deeds provoked. Art criticism, Rosenberg insisted in his most important and widely misread essay, ‘The American Action Painters’ (1952), was the least appropriate of all possible responses to such action. ‘The new painting,’ he declared, ‘has broken down every distinction between art and life,’ and required not criticism in the sense of a specialist’s evaluative search for quality, but rather an existential exercise of judgment. Instead of delineating an artwork’s place in the unfolding of historical tendencies, or revealing its interest as a lens onto social problems, the critic must judge the artist’s action for how it reveals a life.

Rosenberg’s own life, which is better known thanks to the 2021 biography by Debra Bricker Balken, began in a lower-middle-class Jewish family in New York in 1906. Ambitious but unfocused, Rosenberg wandered after law school (he never practised as a lawyer) amid the bohemians of Greenwich Village. Through his friendships with young would-be artists and intellectuals, he acquired a familiarity with the main currents of his era: Marxism, psychoanalysis and surrealism. Rosenberg’s creative activity was as eclectic as his intellectual milieu. For much of the 1930s, he shifted his energies restlessly among painting, poetry, fiction and nonfiction. All these efforts were informed by his Leftist politics. For example, his poem ‘The Front’ (1935) finds Rosenberg struggling to master a multi-perspectival modernist style, in which he celebrates violence committed by sailors, union members and farmers against forces of reaction symbolised by ‘some bastard of a business man’.

The WPA’s murals of heroic farmers and workers resemble nothing so much as the art promoted by Stalin and Hitler

As the Great Depression, starting in 1929, became an era-defining disaster, Rosenberg, like many young thinkers, found inspiration for a new model of society in the Soviet Union. During the mid-1930s, the Soviet government encouraged communist groups throughout the world to collaborate with the non-communist democratic Left as part of the so-called Popular Front. Rosenberg joined a number of these, working as an editor at Art Front, a Popular Front-inspired periodical created by two Communist Party-affiliated artists’ unions. He also joined a series of New Deal-era public works projects aimed at providing employment to writers and artists. He wrote catalogues and other texts about murals funded by the Works Progress Administration (WPA), and put together an anthology of new US writing, American Stuff, organised by the Federal Writers’ Project. It seemed in those years possible to imagine a series of partnerships linking artists, writers, the American Left, the Roosevelt administration, and international communism.

By the end of the 1930s, Rosenberg had abandoned this synthesis. Like many on the Left, he was bitterly discouraged by the Soviet Union’s show trials and purges, its pact with Nazi Germany and its invasion of Finland. He was disappointed, too, by the narrow, doctrinaire attitudes of Stalinist-inspired activists on the US art scene, and the bland, backward-looking art subsidised by the WPA. Its murals of heroic farmers and workers resemble nothing so much as the art promoted by Stalin and Hitler in their own regimes. The Popular Front, in politics and aesthetics, seemed to have reached a dead end.

Poster for the Works Progress Administration. Courtesy Wikipedia

The artists in Rosenberg’s circles shared his sense of disillusion. One of his closest friends in the 1930s was Barnett Newman (1905-70), a substitute public-school teacher who painted in his free time. Like Rosenberg, Newman was a Marxist of an increasingly freethinking bent. He ran for independent mayor of New York City in 1933, promising that ‘men of culture’ like himself would deliver ‘action’, the term that would later become Rosenberg’s watchword. Those capable of ‘aesthetic experience’, Newman argued, should rally together in defence of the common man against the moneyed interests. His platform offered free art schools, ‘a civic non-commercial art movie studio’ and similar programmes. By the end of the decade, Newman lost faith in the Left and in politically engaged art. In a conversion that would inspire Rosenberg, Newman destroyed his paintings and began to search for a new style that would lead to his breakthrough work of austere abstraction Onement I in 1948.

Onement I (1948) by Barnett Newman. Courtesy MOMA. Gift of Annalee Newman © The Barnett Newman Foundation. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Copyright Agency, 2025

Yet, as Newman would later recall, Rosenberg pressed him throughout this crisis to ‘explain’ what his new style, devoid of any figures or symbols, ‘could possibly mean to the world.’ Appearances notwithstanding, abstract painting, as a response to political impasse and the apparent collapse of hope for a progressive Left, was still political – indeed, Newman told Rosenberg that, if properly interpreted, his work would mean the end of ‘all state capitalism and totalitarianism’. However much its message now required deciphering with help from a sympathetic intellectual like Rosenberg, Newman’s painting could still be a political act. As the two friends navigated their mutual loss of ideological certainty, Rosenberg was helping Newman find a new artistic method – while inventing for himself a new persona as an art critic.

They were more susceptible to bamboozlement as they imagined themselves to be intellectually independent

Throughout the 1940s, as he encouraged Newman in his self-transformation into an abstract artist, Rosenberg doubted whether fruitful political action really was still possible. He worried, indeed, that political progress was thwarted precisely by the appeal of apparently novel personas. Writing chiefly for the small-circulation but highly influential Trotskyist journal Partisan Review, he argued that ‘ex-Communist’ intellectuals like himself, as they drifted from the Left, were so ‘baffled in the face of the present world situation’ that they might pick up any ‘religious or mythological device’ for the illusion of understanding what part they should play and who they should be. Bewildered people, feeling that something was desperately wrong with modern society but unable to explain their situation, much less discover a way out, took on fantastical identities – as Aryans, as the New Soviet Man, as defenders of Western civilisation – in dramas set in the distant past or utopian futures. Although false, these new identities and dramas were at least comprehensible. They provided a script, telling disoriented individuals who they were and what they should do, giving them the feeling of being able to act.

This analysis, which Rosenberg would articulate in a series of essays re-interpreting Karl Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852), echoed the ideas Arendt was developing in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951). Both thinkers argued that extremist ideologies of the Right and Left responded to the real problems of modern society by offering illusory collective identities and narratives that substituted for genuine action and an authentic self. Liberals who opposed these ideologies, they warned, were no less susceptible to such illusions. Indeed, Rosenberg came to suspect that ‘little magazines’ like Partisan Review and the post-Stalinist New York intellectual scene were actually purveyors of this kind of mistaken thinking, and that intellectuals who took themselves to be freethinkers were as deluded as the masses entranced by Stalin and Hitler’s propaganda.

In his essay ‘The Herd of Independent Minds’ (1948), Rosenberg attacked Partisan Review, among others, for their pretension to constitute a world of culture and intellect set apart from the debased mass culture of US capitalism. Partisan Review writers like Clement Greenberg and Dwight Macdonald bemoaned the rise of a consumerist, hedonist, schlock-mongering entertainment industry as much for lowering intellectual standards as for its power to distract the working class from substantive politics. While he shared their concerns, Rosenberg insisted that such publications fostered the false sense of being outside of and superior to the standardised production of public opinion through the media. In fact, they were only a particular demographic within that vast process of manipulation, perhaps all the more susceptible to bamboozlement since they imagined themselves to be intellectually independent. In promoting a smug conformism disguised as free thinking, the little magazines, he warned, were drifting into dithering liberalism that substituted a cozy in-group identity for real possibilities of intellectual and political action.

Such frustration was a dominant theme of the essay that launched Rosenberg’s career as an art critic, ‘The American Action Painters’. Published in 1952 in ArtNews, a publication that was becoming the key venue for writing about the emerging group of New York-based abstract painters like Newman, de Kooning and Pollock, the essay asserted that these artists were emblematic of the difficulties facing everyone living after what Rosenberg called the ‘grand crisis’ of the 1930s and ’40s. Belief in progress of any kind, whether through political revolution led by the organised Left or an avant-garde of modernist artists building on the innovations of the past half-century, had become untenable. It was no longer clear what art was for. Proponents of the ‘new painting’ responded to this situation by abandoning both politics and aesthetics – the goal of either changing society or of creating beautiful, interesting or otherwise significant objects. They sought instead, with ‘a desperate recognition of moral and intellectual exhaustion’, to ‘act’ through the creation of artworks ‘in the form of personal revolts’.

They were, in the field of the visual arts, akin to the existentialists of French literature and philosophy, with whom Rosenberg was intimately familiar as a regular contributor to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir’s journal Les Temps modernes (for which he’d written an earlier version of ‘The American Action Painters’). Critically, Rosenberg differed from his French existentialist interlocutors in stressing that such efforts are not to be judged in terms of their authenticity; they are not a matter of ‘being true to oneself’ or remaining ‘committed’ to arbitrary choices. In referring to them as action, he stressed that these experiments should be judged for their effectiveness in changing the situation and character of those performing them.

Rosenberg argued that the abstract artists could not be understood as art in the traditional sense

Rosenberg was not celebrating the American artists whose efforts he described. Notably, he didn’t name any of them nor describe any specific work of art. Contemporaries recognised, however, that he was referring to the leading abstract painters of New York – Rosenberg, after all, was known to be friends with Newman and de Kooning. Nor was he unique in taking them to be significant artists, or in bringing intellectual attention to the rise of American abstraction after the social realism of the New Deal era. These painters were being heralded by Rosenberg’s colleagues and rivals from the little magazines, most notably Greenberg, who saw them as achieving the next advance in art history, moving ahead in the long evolution away from canvases focused on images towards the liberation of pure form and colour. Soon the abstract painters, particularly Pollock, would become celebrities, lionised as cool rebels whose tough-guy postures matched their aggressive brushstrokes and techniques of splatter. The sputtering hostility of conservative critics in The New York Times only increased their aura of rebelliousness.

Rosenberg took a stance towards American abstraction distinct from Greenberg’s formalist appreciation, the media’s mythmaking or the incomprehension of conservatives. Against Greenberg – and almost sounding like a reactionary nostalgic for the good old days of the academic Beaux Arts – he argued that the work of the abstract artists could not be understood as art in the traditional sense. It was not the latest phase of art history; its very existence showed that art history was as dead as the ideologies of Marxism, nationalism and liberalism. Some people might still be beguiled by beliefs and identities that belonged in the 19th century, but they no longer disclosed paths forward for individual and collective action. ‘Modern Art,’ he declared, was a mere ‘comedy of a revolution’. He thus linked it to the pseudo-revolutions by which the working classes of Europe had been bamboozled by the extreme Left and Right, or the farce of Napoleon III trying to repeat the career of his uncle.

If he could no longer believe in the Popular Front’s promise that art and the Left could combine forces against oppression, Rosenberg was not going to fall back on the pre-Marxist illusion that art had a history separate from that of politics. He likewise questioned the mystique of the artist as a brave, singular individual still resolutely capable of self-expression in a steadily more oppressive and opaque world. This vision held out hope that, amid the collapse of political prospects for a more just future, there might be a way to keep alive techniques of self-creation by which individuals could escape routine, cliché and illusion, and with which they might someday revive political life. Forging a new ‘identity’ through ‘action’, exemplary artists might call attention to our shared capacities for ‘personal revolts’ and draw around themselves a ‘genuine audience’ alert to the ‘new creative principle’. There was an awful risk, Rosenberg warned, that this emphasis on small-scale acts of symbolic dissent might degenerate into a ‘religious movement’, a cult in which famous personalities and objects were venerated by a priestly ‘caste’ of experts, forming a new in-group as deluded as the readers and writers of the little ex-socialist magazines. His most urgent concern was, in fact, to warn against the danger of a growing art market and institutional ‘taste bureaucracies’ subsuming abstract art. He was sceptical whether the ‘personality-myth’ of the ‘lone artist’ was a true resource for resistance or a lure by which artists would let themselves be co-opted.

Over the following decades, until his death in 1978, Rosenberg tried to protect what he saw as the fragile potential of American abstraction for authentic personal and political resistance from its opponents, misguided enthusiasts, as well as the media and a growing art-world establishment. Some of his most cogent writings concern the legacy of his old friend Barnett Newman. While the first wave of postwar American abstract artists to achieve critical and commercial success, like Pollock and de Kooning, were noted for dramatic brushstrokes that seemed to express strong, eccentric personalities, Newman’s paintings were almost impersonal in their austerity. Their only nod to the gesture-heavy painting of his contemporaries was a single line down the centre, which he playfully called a ‘zip’. Newman died in 1970, shortly before his work became popular among a new generation of artists and critics associated with minimalism and colour field painting, like Kenneth Noland. Themselves exhausted by the heroic posturing and ‘expressive’ painting of Pollock and de Kooning, they hailed him as a forerunner of their own style.

Newman’s ambitions more resembled those of the biblical prophets than of Picasso

In essays and a posthumously published monograph, Rosenberg fought to establish Newman’s independence both from his more celebrated contemporaries and from those who claimed him as an ancestor. Partisans of the first group, he lamented, had ignored Newman’s ‘originality’, while those of the second ignored his ‘philosophy’, which sought to create ‘sublime’ experiences for an age in which traditional religion had disappeared. Many of Newman’s titles for his works, like The Stations of the Cross (1958-66), referred to religion, while the works themselves were empty of any visible religious content.

Newman’s approach, Rosenberg argued, was deliberate ‘naivete’. Newman had been committed to his ‘own sense of things regardless of prevailing opinion’, staking the meaning of his work – and his whole life – on the apparently absurd prospect that ‘the repeated image of a rectangle with stripes’ could awaken for viewers the ‘lofty themes’ that had inspired the sacred art of the past. The only way to reconnect with the experience of the latter, Newman posited, was to use techniques of abstraction as a kind of ascetic purification bypassing art history, moving the spectator ‘beyond the aesthetic into an act of belief’, in a sublime without theology, ideology, ritual or creed. Rosenberg admitted that this was heady stuff. It made art critics uncomfortable, implying as it did that art criticism, even the category of ‘art’ itself, was irrelevant to Newman’s ambitions, which more resembled those of the biblical prophets than of Picasso, Pollock or Noland. But this was what action entailed – breaking with conventions, turning art against itself, refusing to support either stale traditions or trendy labels, and taking the risk that one’s acts, indeed one’s life, might have been in vain.

While Newman appears in Rosenberg’s writing as a secular saint, Andy Warhol appears as a Judas or devil. In the 1960s, as the New York art scene turned to Pop Art, Rosenberg attacked what he considered the grotesque and growing complicity of artists with elites, celebrity culture and capitalism. Warhol had fulfilled the grim prophecies of ‘The American Action Painters’ by showing ‘that art-world evaluation of the objects presented to it could be programmed by mustering attention around the artist.’ Rather than the construction of a persona being a difficult, heroic work through which the artist managed to preserve a degree of freedom from an oppressive society and dehumanising economy, it had become only another technique of media savvy and ‘capital accumulation’. Rosenberg’s hostility to Warhol has earned him no favours among subsequent generations of critics and art historians, for whom Warhol’s portraits of Jacqueline Kennedy or dollar signs appear as fascinating immersion in capitalist culture or even as subtly subversive. But just as Rosenberg was never an uncritical admirer of abstract expressionism, neither was he a committed foe of art that anticipated postmodernism or played with popular culture.

In the mid-1970s, for example, he praised Saul Steinberg, an artist who often contributed drawings to The New Yorker (such as ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’). Steinberg’s success in a mainstream publication, and in the medium of ‘cartooning’, Rosenberg argued, had blinded his contemporaries to the fact that he was seeking, on his own terms, new avenues for what Rosenberg called action. His ‘ultimate subject matter’, Rosenberg claimed, was not jokes but ‘style’ itself, and the ways that different styles can be subsumed into a ‘pictorial autobiography’ that both reveals and conceals the artist’s self. Working within mainstream cultural institutions, immersing himself in historical references and cultural trends, Steinberg tried to innovate them from within to open up avenues for experimentation. This was almost the reverse of the strategy pursued by the ‘lone artist’ Rosenberg analysed in ‘The American Action Painters’ and akin, in many ways, to the one pursued by Warhol. If both the pose of the isolated, marginal creator defying social conventions and that of the freethinking intellectual rejecting mass society had become deceptive guises for a failing liberal order, then perhaps the solution, after all, was to work out paths for action from within, and not outside of, the structures that seemed to thwart it.

Original drawing of ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’ by Saul Steinberg for The New Yorker front cover, 29 March 1976. Private collection. © The Saul Steinberg Foundation. Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Copyright Agency, 2025

Americans, grown understandably cynical, might stop believing in any kind of political identity or action

The Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal added fresh urgency to Rosenberg’s longstanding search for a persona that could permit resistance to what he saw as the systematic deceptions of US politics and culture. The Johnson and Nixon administrations had lied to the public for years about the nature and extent of what he saw as a monstrous, doomed war in southeast Asia. They had done so with the complicity of the media and the academic experts who filled the Department of Defense and think-tanks. Rosenberg was in no way comforted by the fact that professional journalists had exposed the fabricated Gulf of Tonkin incident or Nixon’s cover-ups. He argued that lies were so widespread, and so often mixed with true or plausible information, that it was becoming impossible for members of the US public to form ‘any objective conception of what is taking place’.

The public, he suggested, was right to lose confidence not just in individual politicians, journalists and scholars, but in all who filled those roles. But it was wrong to withdraw into what was becoming its ‘typical response’ of ‘acedia’ and ‘indifference’. While, a generation before, Rosenberg had worried that the public and intellectuals alike were easy prey to the deceptions of Stalinism, fascism, nationalism, Christian conservatism or liberalism, he now feared that Americans, grown understandably cynical, might stop believing in any kind of political identity or action. In such an atmosphere, he insisted, it becomes more critical still for writers, like artists, to show that ‘in action there is always the chance that something unforeseen will present itself.’ One of the few forms of action is for intellectuals, putting aside any claims to expert knowledge, to express in a compelling, personal ‘style’ their own reactions to what they see – with honest disgust and outrage, rather than cool, dispassionate investigation or critique. Instead of reaching for the mask of ‘the expert’ posing as a master of impersonal facts (a role for which the public now had only well-earned contempt), the intellectual who wants to reach the public should become a ‘participant in the family table talk’, speaking straightforwardly (albeit in an ‘unusually brilliant’ way) about things we all see and feel. In an era that no longer believes in truth, Rosenberg warned half a century ago, the intellectual must become a kind of populist, just as the artist might become a comedian.

Whether Rosenberg was ‘right’ about Steinberg, Warhol or Newman and the abstract artists of the postwar years – that is, whether what he said about them helps us better appreciate real features of their work and its significance – must be for the reader to judge against the visual evidence. What’s most significant about Rosenberg’s criticism is that, as he shifted attention from one artist to another, he consistently sought to evaluate what a given artist’s work revealed about how an individual in our society can use the cultural and institutional resources available to pry themselves out of their old personae and craft a new, more expansive and enfranchising identity. Throughout decades of writing about art, he always held that artists were to be judged for their success or failure at acting – that is, in finding ways to resist routine, cliché and conformity on the one hand, and self-deluded escapism and fantasy on the other. These twin evils, he never stopped arguing, arise from the very nature of our capitalist society.

Few art critics or scholars of art history appreciated Rosenberg’s emphasis on action, or understood its connection to a thoroughgoing critique of the contemporary world. But his friend Hannah Arendt took up many of his ideas in her opus The Human Condition (1958), which argues that political life, like aesthetics, is characterised by an innate, albeit now widely ignored, human need for self-display through performances that are not labour, or routine, or ritual, but what she, following Rosenberg, called ‘action’. Like her friend, Arendt was concerned that possibilities for action in our society were being eroded by mechanisation and bureaucratisation on the one hand, and, on the other, illusory forms of pseudo-action, ranging from the benumbing pleasures of the entertainment industry to the chimeras of mass politics. In an essay that marked a turning point in her thinking, ‘The Crisis in Culture’ (1960), she cited Rosenberg as she began to argue that the task for intellectuals today is not to critique mass culture in isolation from it, but to exercise what she called ‘taste’ and ‘judgment’ within it. In other words, to become a public intellectual following Rosenberg’s example.

In 1979, a year after Rosenberg’s death, his literary executor Michael Denneny gave an interview to the University of Chicago student newspaper reflecting on his time with Rosenberg and Arendt in the late 1960s and early ’70s. In that interview, and in an essay published the same year, he argued that Arendt and Rosenberg were ‘the most important contemporary thinkers on the nature of action.’ They had come, in the course of their friendship, to a ‘unique convergence’ of ideas. Perhaps it is in the nature of action and judgment that they cannot be explained theoretically but can only be practised in concrete cases. In that case, the greatest contributions of Rosenberg and Arendt are the examples they made, in their public writing and in their relationships with students and friends, of their persistent struggle to judge thoughtfully and candidly, even when the criteria for judgment, all the old standards of tradition and certainties of political faith, seemed in doubt.