Hannah Arendt died 40 years ago. Her legacy remains uncertain. Born in 1906 to a secular, assimilated German-Jewish family in what is today Hanover, she rejected the designation ‘political philosopher’, preferring instead to be called a ‘political theorist’. Theory, as she saw it, allowed her to expand from philosophy’s singular man to the experiences of plural men, and to say something enduring about the collective struggle of humanity as it confronted the unprecedented violence of the 20th century.

Of course, what that something was remains elusive, perhaps even muddled. Mirroring the course of her life, her work defied a single programme, embracing instead a host of scattered projects with conclusions that were often as contradictory as they were controversial.

The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), her attempt to understand the Nazism that had uprooted her life and the postwar Communism that she observed from exile in the United States, is vaguely historical in its analysis. The Human Condition (1958), her delineation of the ‘active life’ as the essence of the political sphere, is generally theoretical. On Revolution (1963), her study of the French and American revolutions, reads almost like a love letter to her adopted country, where, in her view, the vitality and diversity of the ancient Greek polis was reborn and reclaimed in the modern age. With Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), the book that emerged from her articles in The New Yorker on the 1961 trial of the Nazi Adolf Eichmann, she ventured into reportage, coining a phrase – ‘the banality of evil’ – and inciting in the process a ‘civil war’ among New York intellectuals.

Arendt was not just a spectator to the Holocaust. Driven into exile after 1933, she went first to Czechoslovakia, then to Geneva, Paris, the French internment camp of Gurs and, finally, to the US, where she settled in New York City. There, she became one of the most prominent figures in postwar American intellectual life. She knew tout le monde: as a student at Marburg in Germany, she’d had a brief affair with her tutor, the philosopher (and future Nazi sympathiser) Martin Heidegger. Later, at Gurs, she was interned with the philosopher Walter Benjamin (a cousin of her first husband Günther Anders); Benjamin committed suicide in September 1940 to avoid Nazi capture.

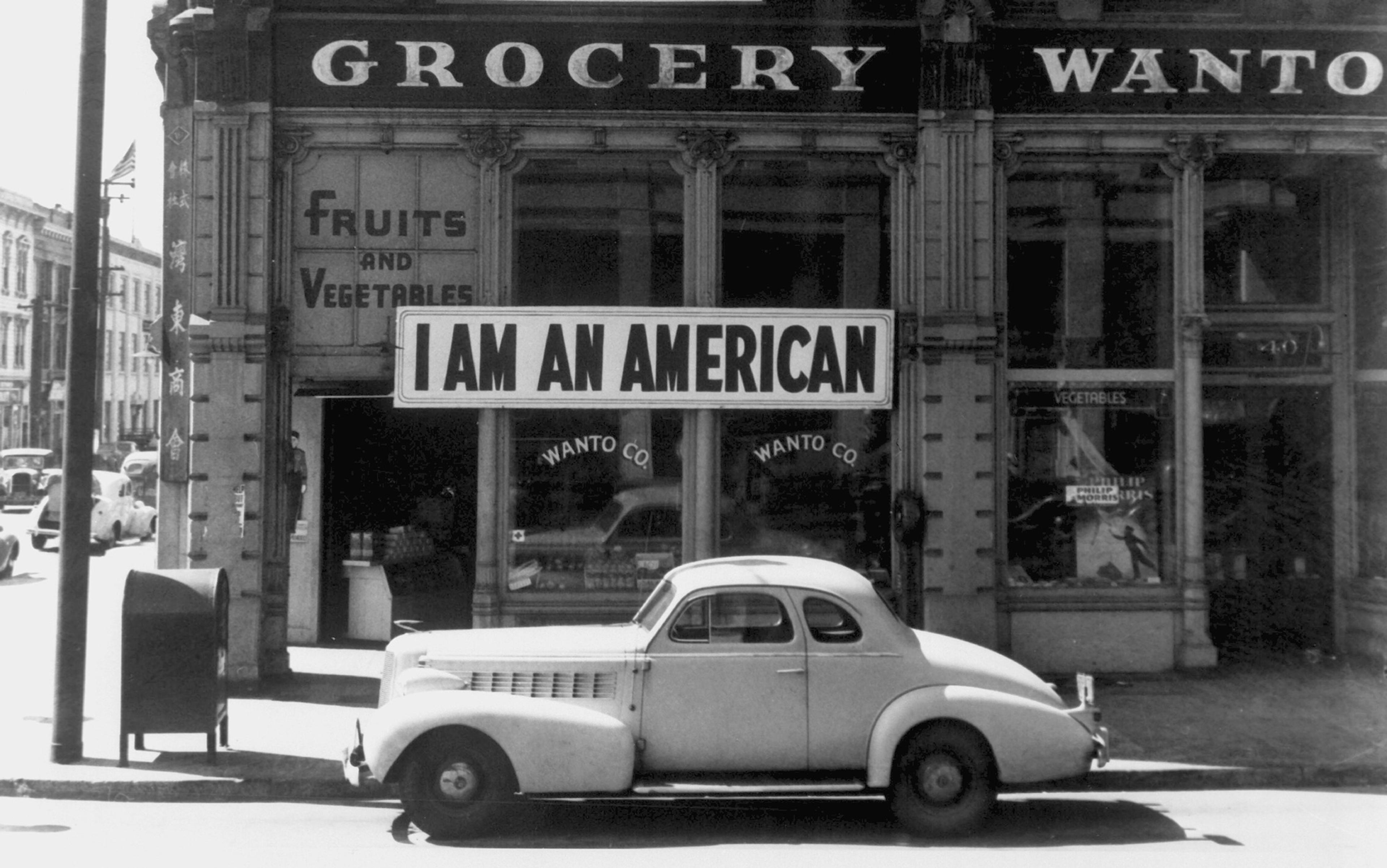

Arendt survived, and she was among the millions of deracinated Europeans forced to remake themselves on foreign shores, in foreign languages. As she wrote in her poignant essay ‘We Refugees’ (1943): ‘A nice little fairy tale has been invented to describe our behaviour; a forlorn émigré dachshund, in his grief, begins to speak: “Once, when I was a St Bernard…”’

This particular émigré dachshund fared well in the US, even if she didn’t always understand its social dynamics. Writing in 1957 about the forced integration of black students in public schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, she said: ‘If as a Jew I wish to spend my vacations only in the company of Jews, I cannot see how anyone can reasonably prevent my doing so; just as I see no reason why other resorts should not cater to a clientele that wishes not to see Jews while on a holiday.’ One winces somewhat at that.

In the US, Arendt was rewarded handsomely for her intellect and tenacity, becoming a bestselling author published by the most prestigious trade presses as well as the first woman appointed to a professorship at Princeton. She also enjoyed a celebrity presence at the University of Chicago and the New School in New York, the stages on which she fashioned herself an eminence in the republic of letters. This is how she appears in Margarethe von Trotta’s 2012 biopic: a dowager queen of Riverside Drive, sparring with pundits such as Norman Podhoretz and Kurt Blumenfeld by day and entertaining authors such as Mary McCarthy and Philip Rahv by night. Add wine, cigarettes and scandal, and this Arendt becomes a kind of monument, the avatar for a bygone era when the literary feud was still a line in the sand, and the personal was not merely political, but ideological.

But there is more to Arendt’s unsettled legacy than glamour, controversy and a provocative set of historical and philosophical interpretations. Forty years after her death, perhaps the most enduring contribution of this decidedly 20th-century thinker is her thinking about a cosmopolitanism suited to the challenges of the 21st century she’d never see.

These days, the term ‘cosmopolitan’ mostly refers to a cocktail, a magazine or anything sophisticatedly international – a restaurant with an extensive wine list, perhaps. London, for instance, is ‘cosmopolitan’ because of its global population and amenities, as are its well-heeled denizens, equally eloquent in French or English, at home both in Paris’ Marais and on Manhattan’s East Side. But when the term is used as a synonym for what used to be called the “jet-set” crowd, a deeper meaning is lost.

Since the release of Wes Anderson’s film The Grand Budapest Hotel last year – the centenary of the outbreak of the First World War – there has been considerable nostalgia for the film’s inspiration, the world of Europe before the wars. Stefan Zweig, the Austrian writer whose work helped inspire Anderson’s film, characterised this bourgeois European ideal as a place where ‘every citizen became a supernational, a cosmopolitan, a citizen of the world’.

Even before 1938, when the German Anschluss moved to make Zweig’s beloved Vienna into what Hitler described as the ‘newest bastion of the German Reich’, Zweig’s cosmopolitan ‘world of yesterday’ was an ideal. Arendt alleged it could be an illusion too, for instance in her 1943 review of Zweig’s sentimental memoir: ‘Had the Jews of Western and Central Europe displayed even a modicum of concern for the political realities of their times, they would have had reason enough not to feel secure.’

what, on a continent of mass graves, do we call the fetishising of an entirely mythic ‘cosmopolitan’ past?

Even ancient Greece, where Diogenes Laërtius first introduced the term kosmou politês, was a deeply patriarchal slave society. Despite the flaws and horrors of ancient Greece, and the modern West, the idea and ideal of cosmopolitanism has fascinated thinkers for centuries. In the Boston Review in 1994, the philosopher Martha Nussbaum advocated what she called a ‘cosmopolitan education,’ one that would create a generation of Americans ‘whose primary allegiance is to the community of human beings in the entire world’. In 2004, the political scientist Seyla Benhabib argued for a cosmopolitan politics that could serve as a model for the legal frameworks of nation states.

As romantic and appealing as these ideas often seem, to some, perhaps a recast 21st‑century cosmopolitanism might better focus on the quantum unit of the single person, the 21st-century individual, who inhabits a complicated, multifaceted identity with any number of (often contradictory) associations and affiliations. With this in mind, a 21st-century cosmopolitanism must take into account cosmopolitan individuals rather than merely an abstract cosmopolitan ethic.

Cosmopolitan individuals are those self-conscious of that fact that there is never a single criterion of identity. While the traditional identity categories of nationality, religion, gender, class and race survive, there are also new vocabularies of identities at the intersections and exteriors of those age-old categories. Many people now have real autonomy in deciding for themselves what each of those identifications means to them, and how much value they wish to assign them. Identity is always a composite in a unified whole. Recognizing the individual as a quantum unit, however, risks ceaseless self-riddling at the expense of external commitments, projects of justice and humanity. A cosmopolitanism for the 21st-century must therefore also not surrender universalism, but acknowledge too that there are also multiple universalisms. People can be rooted in the particular selves of their own design, and they can choose different universal frameworks with which to construct those selves. In other words: everyone is different but no one ‘fits in’, largely because there is very little to ‘fit in’ to.

That, in essence, is the potential for cosmopolitan individuals: people with multifaceted identities who neither sacrifice nor efface their particular affiliations but who can find within those particularities the vestiges of a shared humanity. In his 2007 work on cosmopolitanism, the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah put it this way: the challenge ‘is to take minds and hearts formed over the long millennia of living in local troops and equip them with ideas and institutions that will allow us to live together as the global tribe we become’.

In an increasingly globalised world, those ‘ideas and institutions’ will undoubtedly vary. The best place to start is by recognising that the humanity of those ‘minds and hearts’ is a function of their particularity, and that a meaningful cosmopolitan revival would rely on the fundamental difference of individual identities, not their alleged uniformity.

Hannah Arendt never wrote explicitly on cosmopolitanism, or indeed even used the term, but she was a model cosmopolitan. She loved her adopted US, but never effaced her past to fabricate a new present. Her understanding of Jewish history and her experience of her own Jewishness remained central to her life and to her work, helping to illuminate a disparate, difficult whole. Arendt was fascinated by the concept of ‘the pariah’, the outcast, which in her mind conveyed the Jewish experience in Europe. As she wrote in Origins of Totalitarianism, Jews ‘always had to pay with political misery for social glory and with social insult for political success’.

This was the crux of her cosmopolitanism: uprooted, deracinated, but always resilient

For Arendt, being a pariah was not an inherently negative position; it could also bring a certain value. In a series of essays written in the 1940s, she referred to the poets and writers Heinrich Heine, Rahel Varnhagen, Bernard Lazare, and Franz Kafka as conscious pariahs. By this, she meant they never escaped their Jewishness but also used their difference ‘to transcend the bounds of nationality and to weave the strands of their Jewish genius into the general texture of European life’, who administered ‘the admission of Jews as Jews into the ranks of humanity’. In other words, who did not efface their particularity but celebrated it, finding within it a world of substance on a universal scale.

This was the crux of her cosmopolitanism. Uprooted, deracinated, but always resilient, Arendt was marked by her own dark times, but it was precisely because of them that, throughout her long and audacious career, she could articulate the contours of a cosmopolitan vision more attuned to the world she entered than the world she left behind. Arendt’s life and work is the story of a person seeking the abstraction of a universal humanity from the perspective of a particular community – in her case, the Jewish community (though she was at odds with it nearly constantly).

By recognising what was universal within her own ‘pariah’ status, she was a true cosmopolitan. Among her innumerable legacies is that her memory is a testament to plurality – the notion that people are not all the same, but, in respectful recognition of their differences, can transcend boundaries that have kept them apart. Arendt’s cosmopolitanism was thus devoted not to the supremacy of human life but to the specificity of particular human lives, informed and inspired by difference.

But Arendt’s name is still a synonym for controversy. The reason for this is Eichmann in Jerusalem, which has sold more than 300,000 copies to date. And yet it is this book that best illustrates the nature of Arendt’s cosmopolitanism.

In 1960, the Mossad captured Adolf Eichmann – one of the principal organisers of the Holocaust, charged with coordinating the mass transports of hundreds of thousands of Jews to their deaths – in Buenos Aires. They smuggled him out of Argentina in an El Al flight attendant’s uniform. His ‘show trial’, as Arendt described it, was the first televised event where the world was made to confront the atrocity later called ‘the Holocaust’. Reporting on the first event to give voice to hundreds of victims – some of whom, overwhelmed, collapsed in the courtroom – Arendt displayed no particular sympathy to their experience.

Herself a victim of men such as Eichmann, she had come to Jerusalem to lay eyes on the devil himself, only to find instead a mediocre bureaucrat animated not by murderous rapture but by careerist ambition. Eichmann represented, for Arendt, the ‘banality of evil’, an interpretation that led many readers to wonder whether she had exonerated her villain. But it was the way she treated Jewish victims and survivors – in terms of both the caustic tone she took and the conclusions she drew – that caused the heat of the firestorm.

From the snobbish prejudice of her elite background, Arendt described Gideon Hausner, the chief prosecutor, as ‘a typical Galician Jew, very unsympathetic, boring, constantly making mistakes. Probably one of those people who don’t know any language.’ Meanwhile, the Palestinian Jews outside the courthouse were an ‘oriental mob’. She dubbed Leo Baeck, the erudite Berlin rabbi and wartime leader of the city’s Jewish community, who himself had scarcely survived the concentration camp at Theresienstadt (Terezin), the ‘Jewish Führer’.

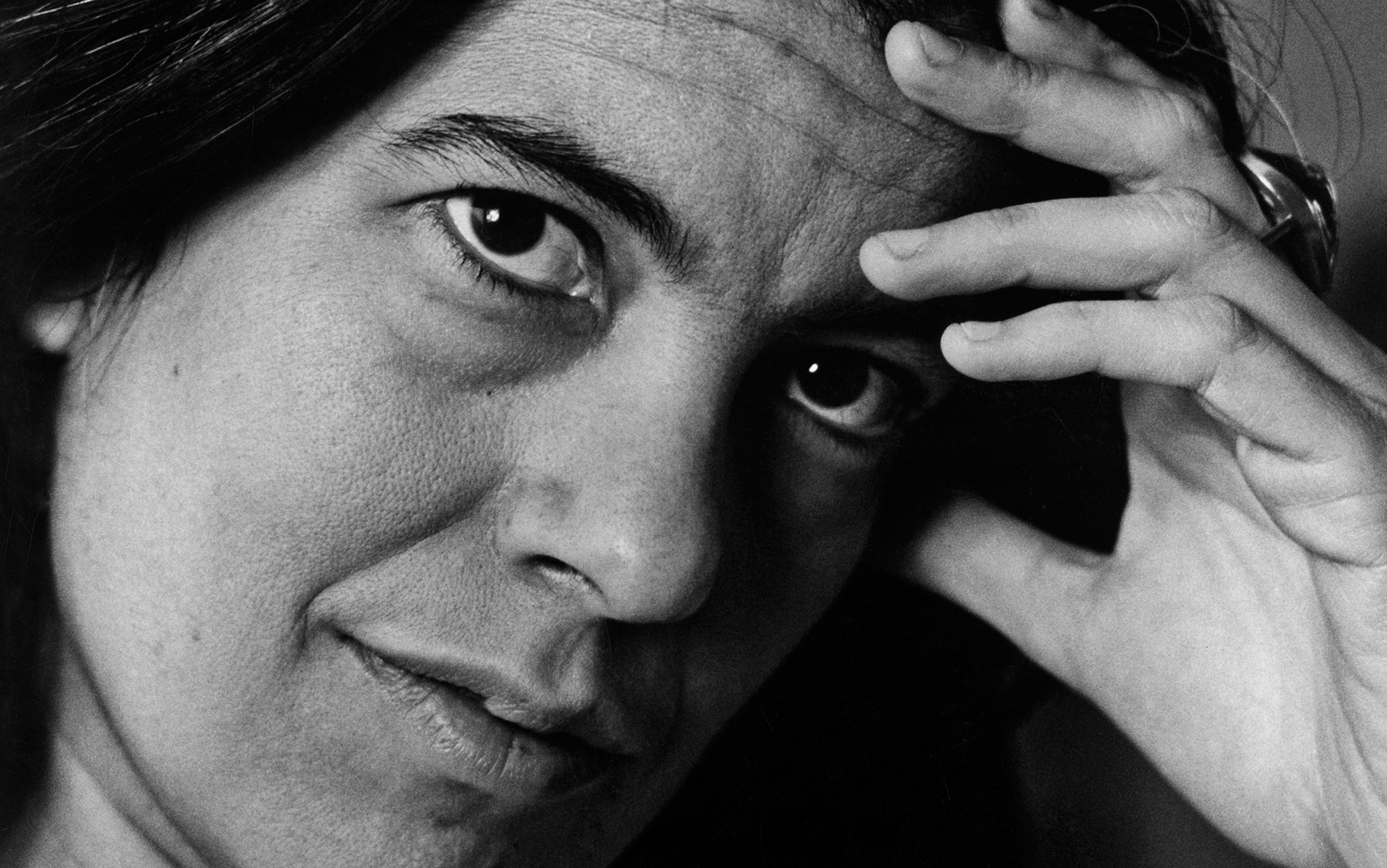

There was a significant gender dimension to Arendt’s pariah status: she was a woman who had invaded the intellectual realm of men

What she wrote on the Judenräte – the Jewish leadership in the Nazi ghettos – would place her at the frontline of a bitter battle between history and memory:

Wherever Jews lived, there were recognised Jewish leaders, and this leadership, almost without exception, cooperated with the Nazis. The whole truth was that if the Jewish people really had been unorganised and leaderless, there would have been chaos and plenty of misery but the total number of victims would hardly have been between 4.5 and 6 million people.

Arendt’s project in Eichmann in Jerusalem was to describe the totality of the moral collapse under Nazi rule, a theme she had already explored in her Origins of Totalitarianism more than a decade before. For Arendt, that the Jundenräte were made complicit in the liquidation of their own people was simply an illustration of that totality, a haunting landscape in which the perpetrator transforms the victim into a perpetrator himself. Unfortunately, her tone obscured her point. The book incited what one prominent critic called a ‘civil war’ among New York intellectuals. As the historian Anthony Grafton wrote in 2009, recalling his childhood in the secular Jewish literary circles of 1960s New York, it seemed that ‘in the world’s largest Jewish city – in the nation’s most serious, best-edited magazine – Jew had apparently betrayed Jew’. With one short book, Arendt, an eminent political theorist, had herself become a pariah.

There was a gender dimension to Arendt’s pariah status (as there was for Varnhagen, the 18th-century assimilated German-Jewish salonnière whose biography Arendt had begun in the 1930s). Arendt’s friends and critics regarded her as a woman who had invaded the intellectual realm of men. In 1964, for instance, she appeared on Zur Person for a TV interview with Günter Gaus, a German equivalent of Charlie Rose or David Dimbleby. ‘Hannah Arendt, you’re the first lady to be portrayed in this series,’ Gaus began. ‘A lady with a profession some might regard as a masculine one. You are a philosopher.’

Similarly, in his review of Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s biography of Arendt, the US literary critic Alfred Kazin introduced his subject not as a thinker but as a woman, confined to the domestic space of the ‘shabby rooming house on West 95th Street’ she shared with ‘her strenuous husband’, the German poet and philosopher Heinrich Blücher. ‘She was a handsome, vivacious 40-year-old woman,’ Kazin wrote in The New York Review of Books in 1982, ‘who was to charm me and others, by no means unerotically.’

As constraining as these prejudices were, they did not imprison Arendt. They were the reasons for her pariah status, to be sure, but they were also the foundations of her particularity, and the essence of her cosmopolitanism.

In the aftermath of the Eichmann controversy, Arendt had a heated exchange of letters with her friend, the German-born Israeli philosopher Gershom Scholem, who’d questioned her right to judge events at which she’d not been present. ‘Nor do I presume to judge,’ he wrote in 1963. ‘I was not there.’

More central to his objection, however, was what he considered to be Arendt’s lack of Ahavat Israel – love of the Jewish people. Arendt’s response says something about her particular view of cosmopolitanism:

I am not moved by any ‘love’ of this sort, and for two reasons: I have never in my life ‘loved’ any people or collective – neither the German people, nor the French, nor the American, nor the working class or anything of that sort. I indeed love ‘only’ my friends and the only kind of love I know of and believe in is the love of persons.

Regarding his questioning of her Jewish identity, she wrote:

To be a Jew belongs for me to the indisputable facts of my life, and I have never had the wish to change or disclaim facts of this kind. There is such a thing as a basic gratitude for everything that is as it is.

Her response is ultimately an emphatic defence of her own pariah status. What she conveys to Scholem is that her Jewishness, an ‘indisputable fact’ of her life, is ultimately a particular association she refuses to denounce because of the potential it affords her as an element in her identity.

The letter recalls the final scene of her 1957 biography of Varnhagen, who, in many ways, is Arendt’s alter ego. In an embellished quotation – Arendt omitted pieces of Varnhagen’s correspondence where she confirms her conversion to Christianity – the author allows her subject to die a peaceful death, having reconciled, at long last, the tension that has governed her life: ‘The thing which all my life seemed to me the greatest shame, which was the misery and misfortune of my life – having been born a Jewess – this I should on no account now wish to have missed.’ The narrator’s voice then returns to give Arendt’s final verdict on Varnhagen: ‘[She] had remained a Jew and a pariah. Only because she clung to both conditions did she find a place in the history of European humanity.’ The judgment applies as well to Arendt.

In certain respects, as a Jew in Nazi Europe, a refugee on a checkerboard of nation-states, and a woman in an intellectual world of men, Arendt was a pariah figure. But this isolation also made her an iconic cosmopolitan, not so much a ‘citizen of the world’ as a citizen of several worlds among many others, fully at home in none but adept in them all. If she considered herself a political theorist, she was also herself a living theory, a poet of plurality.