It has been seven years now since I moved from Russia to Germany, and not a month goes by without me landing in the same predicament. A party is in full swing. The plates and bottles are half-empty, the hurdle of small talk has just been overcome, and everybody is in pursuit of one, imperative theme to seal the evening. Then somebody turns to me and asks: ‘How do you, a Russian — a Russian Jew, to be precise — feel in Germany?’

My friends, my relatives and total strangers — all seem to assume that I should feel uneasy in the country that initiated the Holocaust and, in 1941, invaded the USSR. ‘How is it possible,’ Germans want to know, ‘that you do not hate us?’ And my Israeli and Russian friends ask: ‘How is it possible that you do not hate them?’

For a long time, I didn’t have an adequate response to this question. I could urge forgiveness for Germany’s past, pointing to the admirable features of its present, but this sounded like an apology at best, and evasiveness at worst. Love makes all justifications sound unconvincing, and what keeps me in Berlin is certainly love — an inexplicable attachment to its bleak architecture, its sour humour, its dialect, flat and broad like the Prussian landscape. For years, something crucial, something pivotal that would free me from having to defend my choice, was forcing itself through the wire of small talk. But it never managed to get out.

Then, one day not long ago, I found the answer, and it came from a most unexpected source. My grandfather, it transpired, had kept a diary during the Nazi Siege of Leningrad (now St Petersburg), in which at least 750,000 people died from starvation and bombings between 8 September 1941 and 27 January 1944.

His diary had been shut away in a black wooden box for almost 70 years. Immediately after the war, it would have been simply dangerous to expose its contents. The ideologues of the Soviet state were busy constructing their own heroic narrative of the Blokada, depicting Leningraders as a single integrated organism, withstanding the atrocities of a German invasion with their heads held high. Great effort went into suppressing all accounts that might challenge the official story. Oral histories and private documents were only tolerated to the extent that they confirmed it.

Joseph Bassin, my mother’s father — 27 years old, plump, Jewish and bespectacled — found himself trapped in the Siege by pure chance

None of this is to deny that heroism and self-sacrifice were plentiful. The stamina of Leningraders is not to be gainsaid. However, details about the ruthlessness, cruelty and neglect that inevitably accompanied the fight for survival were buried for years. Thousands of Soviet people grew up with a sterilised notion of the Siege. Even in families of survivors, children often learnt nothing but the publicly acceptable narrative: either their parents wanted to protect them from the horrors of what they witnessed, or they had been taught to keep their mouths shut. It was only with the onset of glasnost in the late 1980s that shocking stories from the Siege began to emerge. Marauding, looting and even cannibalism were all revealed, as well as treason and venality on the part of the Party authorities.

By that time, my grandfather was already dead. Another Siege survivor in my family — Frida, my grandmother on my father’s side — refused to discuss the months she spent in surrounded Leningrad, even though she had an extremely ready tongue for all other occasions. I grew up with the understanding that the Siege was not to be mentioned at home. Like my parents, I learnt about it from books.

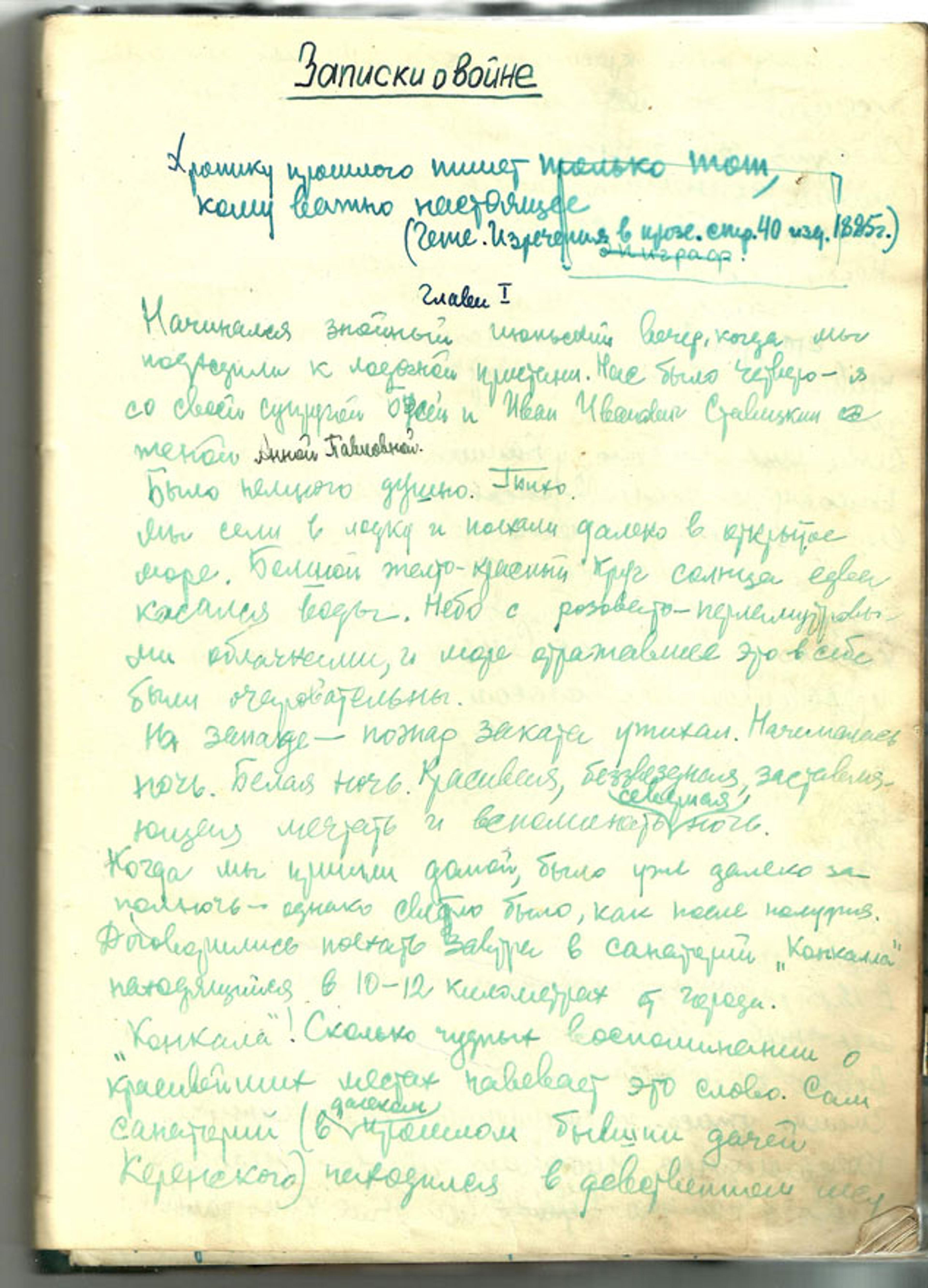

And then, last year, Frida died. The vow of silence that was meant to protect her from her memories could now be broken. My mother and I decided to climb the ladder in the home we had inherited from Joseph and remove that black wooden box from its place on the top of a bookshelf. Inside was a thick notebook with an oilcloth cover, filled with neat handwriting. It was absolutely undamaged. The title on the first page read ‘Notes on the War’. An aphorism from Goethe was scribbled below: ‘The one who writes the chronicles of the past, is the one who is willing to comprehend the present.’ An apt quotation, as it turned out.

On a bright September evening in 1941, huge puffs of something white floated in the Leningrad sky: ‘For simple clouds they were too gorgeous,’ my grandfather observed, watching as they turned scarlet in the setting sun — ‘a stunning, but menacing sight’. He was right to worry: hanging over the city was a cloud of dust from Leningrad’s grocery warehouses, which were burning in shell fire. A mix of flour and sugar hovered over the city all night. In the morning, the Baltic wind blew it away. Nothing but several square miles of burnt soil, permeated with grain shreds and oily syrup, was left to feed a city of three million for the coming months.

My grandfather watched the blaze from the window of a crowded evacuation train, squeezed between hundreds of people:

The air was muggy, stinky and oppressive; it reeked of flatulent refugees engorged with bread and beans. It was terribly filthy, and worst of all, there were lice everywhere. An old man in my compartment was infested with at least a million fat, shiny parasites, but it didn’t matter how much we begged him to move away into the corner, he only grunted and did nothing at all.

Worse than the dirt and stench was the overwhelming uncertainty. The news on the radio was vague. Nobody seemed to know exactly where the Nazi troops were, not even the railway administration. The train changed its destination every day, sometimes spending hours in the middle of a field waiting for the Luftwaffe’s attacks to pass over. The whole situation was extremely vexing to my grandfather: he never meant to be on that train. He knew that his place as a Communist and as a family man was elsewhere.

Indeed, Joseph Bassin, my mother’s father — 27 years old, plump, Jewish and bespectacled — found himself trapped in the Siege by pure chance. He wasn’t even from Leningrad.

He had been born in one of those Jewish settlements in the west of Russia of the kind that Marc Chagall painted in the 1920s, before they were destroyed by collectivisation. In his youth, Joseph broke with the religious traditions of his family, joining the Communist movement and enrolling in a technical university in Moscow. There he discovered a new family — a generation of revolutionary young Jews like himself, ambitious students and believers in social progress. One of them, a doctor named Bella, he married. By his mid-twenties, Joseph was a director of a small printing plant in Vyborg, 90 miles north of Leningrad. And that’s where he was when the war began.

In early autumn 1941, he evacuated his plant and sent his pregnant wife away from the fighting. She got out in the nick of time. Local party bosses were too busy taking care of themselves. ‘They panicked first and were the first ones to send their property away,’ Joseph observed. Everyone else had to wait. The transport for Joseph’s workers and their families was assigned at the last minute: a 60-ton half-wagon meant for the transportation of dry goods, with no roof.

Loaded with printing presses and 50 people — the pregnant Bella among them — the train finally left for the east one September night, heading towards Kuibyshev, on the shore of the Volga. Joseph stayed behind to file evacuation papers with the Party Committee. He thought it would only take a few hours, but the next morning, trying to catch up with his convoy by car, he discovered that there was no longer any way out. Only one road remained open and it led to Leningrad. Having no alternative, he turned the car around. Little did he know that the Nazi Ring was closing behind him.

Joseph wrote: ‘One can stay human only under human conditions — or one turns into an animal’

In Leningrad, he found himself drifting aimlessly from one refugee camp to another, boarding dozens of trains that went nowhere. He was losing time. It wasn’t only the fate of his wife and their unborn child that worried him; the plant was weighing on his mind, too. There were important papers in his briefcase — the kind of papers without which no printing press could be assembled, no worker paid a salary. Joseph cursed the Party bosses for procrastinating, but no matter how many times he told the authorities that he was a director, it didn’t help. After trying for six weeks to break through the front line, he resigned himself to staying in Leningrad. It might have been worse: his wife’s relatives lived in the city, and his younger sister had just started to study there. Thus the Siege clasped him in its arms for the months to come.

During those first October weeks, Joseph was bored. No letters came: not from his parents, neither from his wife, and not from his friends at the front. He longed for news so badly that he started hallucinating: ‘A neighbour has just passed by and announced: “Mail for you! Five letters!” I have jumped to the ceiling, but she only brought a newspaper. False alarm. My heart is still beating like mad.’

The hunger was already setting in but my grandfather didn’t feel affected by it yet. His primary concern was to make himself useful. He hovered around the city, frustrated and impatient to contribute to ‘the Victory’. He applied to the army several times but was turned down because of his high qualifications. A Communist in his heart, he felt he was involuntarily betraying the Motherland. On 24 October 1941, Joseph wrote:

Among many other street posters I see every day, there is the one with a Red Army soldier holding a gun in one hand and pointing to you with the other. ‘What have you done for the front?’ he is asking. And indeed, what have I done for the front, particularly in the last few days? In the first two or three months of the war I was still in charge of a plant that published weapon manuals, propaganda leaflets and other useful print material, but now I am realising my worthlessness.

A few days later, local authorities assigned Joseph the job of political instructor in the Leningrad Red Cross. The role did provide him with food stamps, but it didn’t make him feel much better about himself.

As the Siege progressed, Joseph’s sense of normality kept stretching like a piece of grey rubber, accommodating ever more forms of privation. ‘The shells are exploding somewhere very close, perhaps in our street, but I don’t care any longer,’ he wrote. ‘I got used to it and am so fed up that I think death itself would be better than this permanent lingering.’

This dull, rubbery reality kept expanding for weeks. Then, one day, it snapped. He read it first in the local paper, and the diary records his shock: ‘52,000 Jews — children, women, men — were murdered by Germans in Kiev. Not 52 Jews, not 520; 52,000!!!!’ He went on:

I want to avenge my mother’s tears, Bella’s sufferings, everything I have seen. The shells exploding outside, they are calling me into battle… In the future someone may ask me what I have done for the victory. And I will answer that I was a Red Cross instructor. It is an important job, of course, but any other educated person could do it equally well. A woman, for example. No, no, as for myself, I am going to the army recruitment bureau tomorrow.

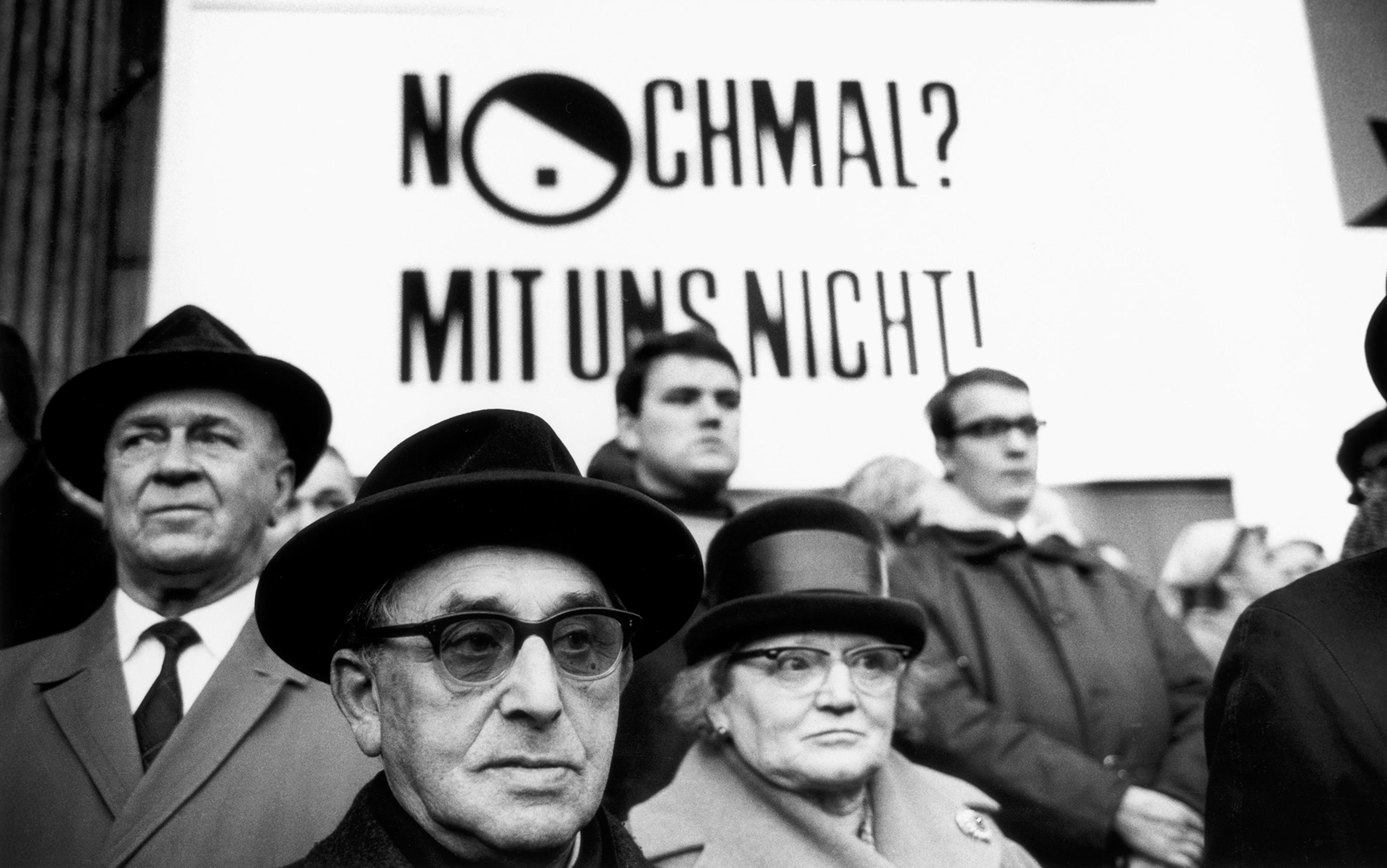

Did Joseph hate the Germans while he was writing these words? And shouldn’t this excerpt from his diary instruct me that I too should hate them, 70 years later? Such conclusions are tempting in their logic — but they are wrong. Joseph’s language alone suggests it. Everywhere in his diary and particularly at this spot he makes a great effort to distinguish between ‘Germans’ and ‘Nazis’. After referring to the enemy as ‘Germans’, he actually corrects himself:

They are not even cannibals, not even animals. They are simply Hitler’s Nazis. Nothing else — just Hitler’s people, a special breed.

Joseph, a Communist Jew, grew up during an era that aspired to global revolution, and German socialists were in its avant-garde. It appears to me that his consistent attempt to avoid the word ‘Germans’ meant that he remained true to the pre-war ideals of international solidarity, in spite of everything. For Joseph, watching his language was a matter of honour: a matter of differentiating between a German such as the communist Karl Liebknecht and one such as the Nazi Heinrich Himmler, between the Germany he loved and the ‘special breed’ of creatures that took charge of it.

True to his word, Joseph applied to the army again and was refused again. ‘We’ve got more need for you here,’ they told him. Having no alternatives, he remained in Leningrad. That year’s winter was extremely cold, sometimes reaching below -40C. The city started to fall apart. There was no food, electricity or fuel. The trams stopped. Then, so did the plumbing:

Whereas earlier one could get water in the laundry, in a house next door or, in the worst case, in the next street, now all of this has become impossible: there is no water anywhere. Somewhere in deep cellars — unfortunately, very far from us — it still continues to drip, and there are queues of 200 or 300 people waiting. All of it taking place in -30C frost. [We] queued from 9am till 2pm and had to return home without water: the dripping ceased before we got to the tap.

Getting water from ice-holes in the city’s frozen rivers and canals became one of the most dangerous winter ordeals: dragging heavy buckets, emaciated Leningraders often slipped, fell and died, freezing, too weak to get up. The streets were littered with corpses, too. Joseph wondered how many he saw each day: ‘Perhaps 30 per day, but it could just as easily be 60.’

It wasn’t just the city but human dignity itself that crumbled under the pressure of unprecedented suffering: a particularly shocking discovery for Joseph, who honestly believed that Socialism was capable of creating a new man — one who remained decent under all circumstances. Referring to a famous statement by the illustrious Soviet writer and ideologist Maxim Gorky, he observed:

You said, ‘A Human — that sounds dignified.’… You probably did not mean that young man, well-groomed and wearing a pin-striped suit whom I saw licking — yes, licking! — his plate in the cafeteria today? And, perhaps, not that old woman who hovered around and picked up bread crumbs from the floor, like a chicken. Not pieces, not bits — crumbs!

Worse was to come. By mid-January 1942, there were no more plates to lick and no more crumbs to pick up. Death itself turned into a subject of trade. Some were taking advantage of the corpses: a colleague told Joseph she saw a female body with buttocks carved out with a knife. The others engaged in a different economy — saving their own fading energy:

A man stood on the staircase and watched the policeman complete a death protocol. The policeman said: ‘With this paper you must go to the City Health Department and get a death certificate. With it, you will go to the registrar’s office and get a burial permission, and then you can bring the corpse to the cemetery.’ The man watched him and contemplated for a minute. I could read his thoughts: ‘How can I possibly run all these errands alone? Where will I get a coffin? Who will dig a grave in this frost? Who will help me?’ After a pause, he turned to the policeman and said: ‘Look, the other one is about to bite the dust, too. She’ll be dead by the evening. I’ll wait till tomorrow and have the papers for them both done.’ This is dignity, this is decency! One can stay human only under human conditions — or one turns into an animal.

Family remained the only place where Joseph encountered kindness, compassion and the ability to reason. He found these especially in his sister, an emaciated student. He loaned her his pass to his workplace cafeteria, because the food was slightly better than at her college. She insisted on sharing her portion with him, and wept that he wouldn’t come to eat with her. ‘She does not listen when I try explaining to her that I am doing much better than herself,’ he wrote.

He learned to treasure spontaneous mercy more than any kind of doctrinaire heroism

Indeed, compared to other Leningraders, Joseph led a ‘luxurious’ existence by his own admission, getting 350 grams (12 oz) of bread per day, a few spoonfuls of watery porridge and something called ‘intestine mince’ — a substance ‘looking like chopped herring and smelling of rotten fish’. ‘I feel ashamed to say it, but I am only a human being, nothing more, and this is why I still keep my job at the Red Cross,’ he wrote in mid-January 1942. ‘To drop this job would be morally correct, but it means starvation.’

By February 1942 it had become apparent to Joseph that everyone in the city would die soon, including him. If hunger didn’t finish them off, then they could count on the epidemic fumes rising from corpses in the streets and from human waste frozen into the ice. Leningraders, it had become clear, were left to their own devices. There was no longer anywhere from which to expect help. Radio broadcasts stopped. Even those last bits of rationed bread — ‘400 grams for manual workers, 350 for clerks, 250 for the unemployed and children,’ as Joseph’s entry on 25 January 1941 noted — had vanished.

And yet, at the bottom of this descent, a choice was waiting for him. After many months of dismissing his every effort to ‘contribute to the Victory’, the authorities had finally heard his plea. They offered him the directorship of a large printing-shop, an offer that an engineer of his rank could only dream of, not to mention a task worthy of a Communist. By accepting it, Joseph would become responsible for printing Leningradskaya Pravda, the one remaining newspaper in the city; the very newspaper, in fact, that had brought him news of the Holocaust three months earlier. Yet at the same moment, a long-awaited evacuation permit arrived. This would be Joseph’s last chance to break out to his wife, to his newborn child, and to his own plant.

My grandfather spent several days contemplating. He experienced the ultimate, abysmal loneliness of a person about to determine his fate for the rest of his life. His sister, he knew, would be taken care of by relatives. But what about him? ‘I feel terrible pain,’ he wrote. ‘It is very difficult. And there is no one around I can share this feeling with. I am a lonely man.’ The next day, he reached his decision. He would leave.

Joseph Bassin departed Leningrad on 3 February 1942. Climbing on to the evacuation train towards the ice road on Lake Ladoga, the only route out of the city, he had even fewer chances of getting to his destination than in the previous September. A German shell might strike them; a crack in the ice was enough to sink a lorry full of refugees: such disasters happened all the time. When it came to it, though, Joseph found himself concentrating on a different kind of horror — that of human ruthlessness:

The train stopped at some passing loop where dozens of railways met. Here we were meant to get into the lorries… Corpses drawn into a pile, undressed and barefoot, looked particularly terrible here, in that place where hunger sufferings were meant to end. But the scariest thing was that everyone, including myself, tried not to notice them and did not really care any longer. We just passed by these wax figures, trying not to look. Then I saw a girl of about 17 years old. She was leaning on the wall, howling. Apparently she was about to die of hunger. A short, sly-looking fellow walked up to her and shook her on the shoulder. ‘Verka!’ he shouted, but she did not reply. She was still breathing. The boy leaned over her and said impatiently, ‘Come, get done already!’ I stood and wondered what he meant. Then the boy shrugged his shoulders, grumbled something and started pulling the girl’s warm boots off. He himself was wearing ankle shoes. I tried interfering and told him he was a bloody son of a bitch, that she was still alive! ‘So what, uncle,’ he replied, ‘She will die in half an hour anyway, and my feet are cold.’ I was so lost that, when I got back to my senses, the girl was already dead.

My grandfather’s diary ends here. But we know that he made it safely across the lake and joined his family a few weeks later. Closing the notebook, I felt that its value was not in revealing some unknown details about the Siege: in that respect, Joseph’s diary added only little to what I, a child of the glasnost era, had already known. Instead, its power lay in how it revealed universal truths about kindness, heroism and the capacity to forgive. My grandfather’s story started with one evacuation train and ended with another. Between those two journeys, the traveller himself had changed. The man who entered the lice-infested wagon at the beginning of the journey was irritated, but confident: he knew right from wrong and never doubted that he had his own role to play in the ultimate victory of Communism over Nazism. Yet his convoy went nowhere. Tortured by famine and uncertainty, somewhere around the middle of the way, he watched himself and his fellow passengers turning from exemplary Soviet people into, as he put it, ‘human beings and nothing more’.

After months of neglect from the system he believed in so fervently, suffering absolute forlornness and alienation, my grandfather realised at last that he was not a cog in an omnipotent mechanism. He was a sliver in the flood. Kindness and compassion, as well as cruelty and selfishness, were not characteristics of social strata, nations or parties; they were integral parts of human nature. Climbing the last train was a man who no longer believed in dogmas — he wasn’t even sure of himself. But he had learned to treasure spontaneous mercy more than any kind of doctrinaire heroism.

After joining the front in the autumn of 1942 and meeting the Victory in Czechoslovakia, Joseph went for professional training to Leipzig — a city in East Germany that was one of the world’s centres of the printing industry. Firing up the presses in shelled-out plants, he must have had frequent cause to ponder that damned question that I have heard so many times: ‘How do you, a Russian Jew, feel in this country?’

I do not know his response. But having read his diary, I am quite sure it did not involve any lust for revenge. After everything he had been through, the sheer possibility of peace, of walking on German soil as an equal, of toiling alongside Germans instead of pointing a gun at them, was a breakthrough. He had survived through the era of violence into the era of reason and compassion, and circumstances had taught him to appreciate these qualities above all others. My grandfather’s transformation from a man of ideology to a ‘simple human being’, and his liberation from the dogma of totalitarian thinking, is the greatest inheritance he could possibly leave for me; an inheritance that lay hidden for 70 years in a black wooden box. Dismissing it, turning down the privilege of loving Germany and choosing to hate it instead, as I am often expected to do, would be an insult. Not an insult to my German contemporaries, but to the memory of Joseph Bassin, survivor of the Leningrad Siege.