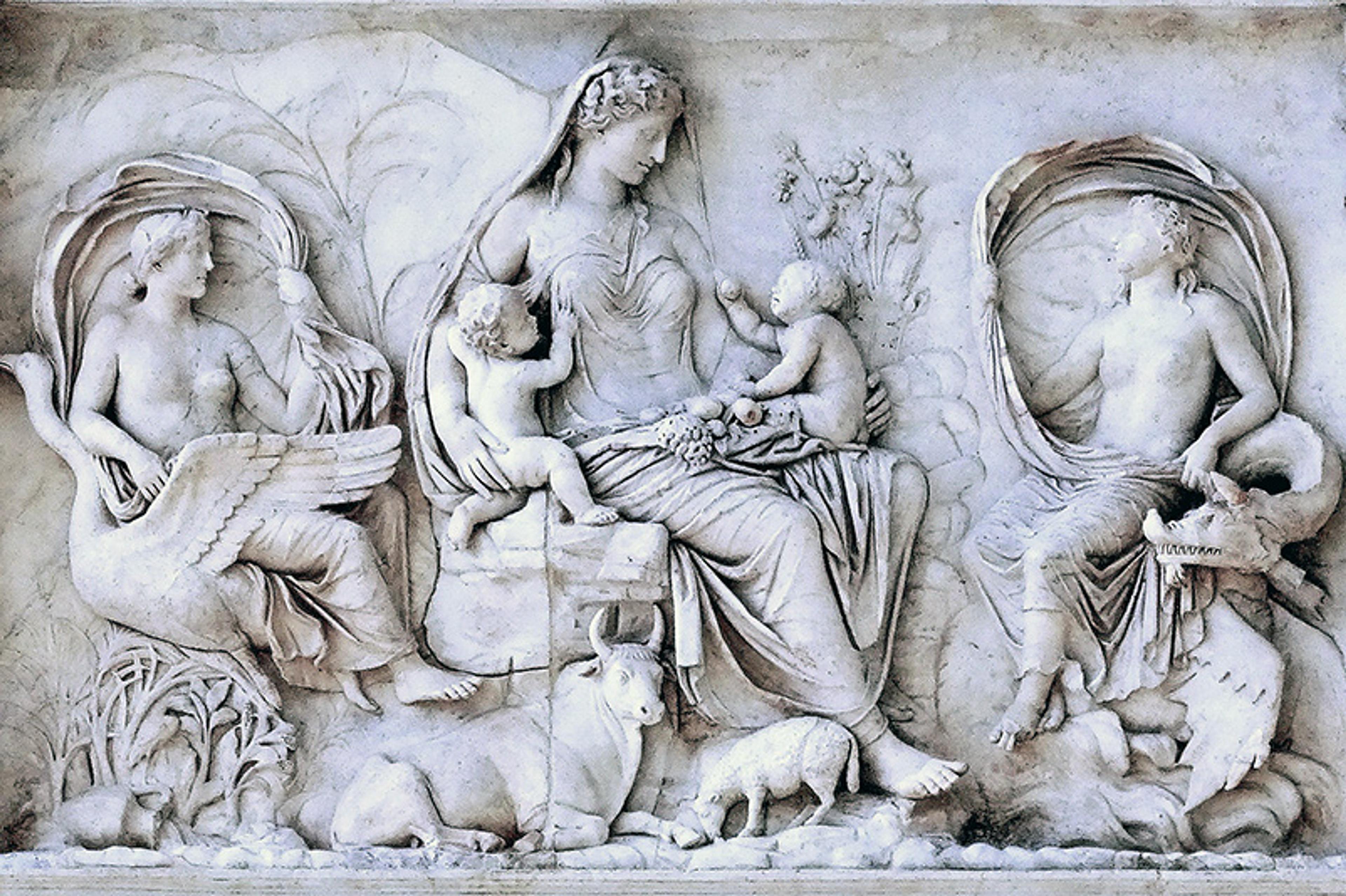

The Altar of Peace in Rome, built in the first half of the reign of Augustus, is a magnificent structure renowned for its architectural beauty and cultural power. Almost 33 feet high and fashioned out of pristine Carrara marble, the panels of the altar are carved into intricate friezes that herald the advent of Pax Romana. On it were depicted the birthplace of Romulus and Remus, Aeneas making a sacrifice to the gods, a grand imperial procession, and ‘vines [grown] from broad acanthus calyxes into treelike forms,’ in the words of the altar’s most influential interpreter, Paul Zanker. There are mysteries, too. Dominating a marble panel to the left of the rear entrance is a divine figure whose identity has been much debated. Clearly, she is a goddess, but which one? She is accompanied by two other female deities. Who are they? And what is the significance of the assemblage of numinous objects surrounding them? The answers, it turns out, lie in how the Romans understood the concepts of time and nature.

Zanker’s analysis of the altar captures the tension between such images of nature’s plenty and the sense of micromanaged design – a desire by the architect to convey a ‘model of perfect order’, as he puts it in The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (1988). Close to the altar was an obelisk, a trophy of Roman imperial expansion into Egypt. This seems to have acted as a monumental timepiece, or gnomon, which cast shadows over the sundial plate (solarium) where it was positioned. Archaeological finds by Edmund Buchner in the 1970s show that the Etesian winds (dry and northern, from the Aegean) and signs of the zodiac were labelled in Greek at points where the gnomon’s shadow would fall. Perfect order indeed.

The Altar of Peace is the centrepiece of an extensive building programme initiated by Emperor Augustus in the 1st millennium BCE. The historians Suetonius and Cassius Dio both report that, towards the end of his reign, Augustus said that he had found Rome built of brick and left it made of marble. In his own grand record of achievements, the Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Augustus claimed to have restored 82 temples in the process. Such structures and images were vital in cementing Augustus’ status as emperor when memories of the Republic were still fresh. Above all, the Altar of Peace emphasised his unique relationship with the Roman people and cosmic time, as the historian Paul Rehak observed in Imperium and Cosmos: Augustus and the Northern Campus Martius (2006).

The Altar of Peace was commissioned by the Roman senate in 13 BCE, coinciding with the return of Augustus from military campaigns in Gaul and Hispania, which drew to a close three years of war. After the commissioning of the Altar, Augustus was voted Pontifex Maximus, chief high priest, so it is not surprising that one of the processional scenes on the altar depicts him attended by Vestal Virgins and members of the ancient colleges of priests. These sculpted reliefs convey the message that Augustus now bestrode the spiritual and political domains of Roman power.

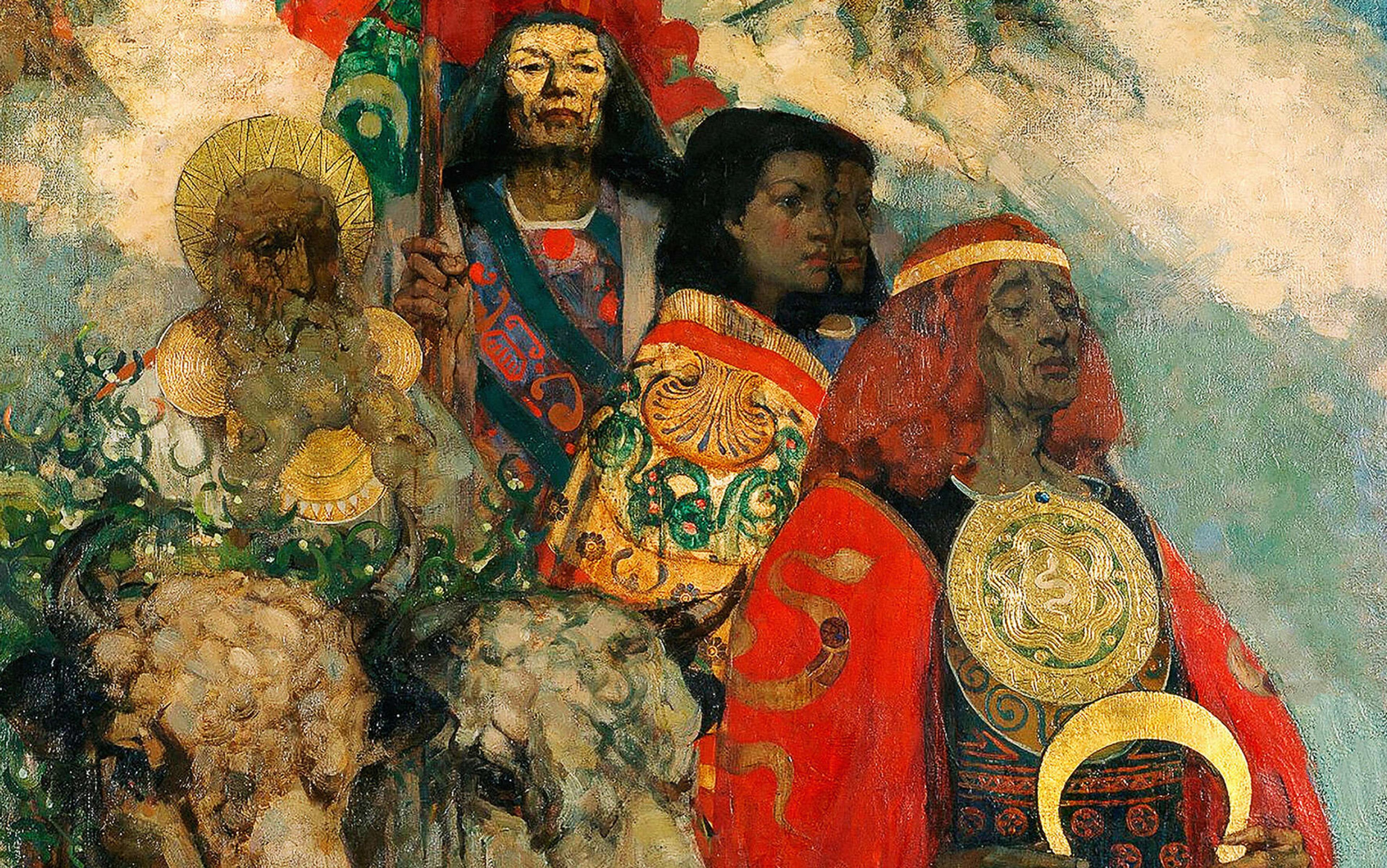

What might be the spiritual and political implications of our mysterious goddess, enthroned amid a landscape steeped in images of the natural world, an embodiment of beauty and fecundity? Some believe her to be Venus, mother of Rome’s founding hero, Aeneas, or perhaps Tellus, goddess of the Earth. But a probable answer is that she is Pax, the personification of the quality that Augustus sought to promote throughout his dominion: peace. In Greek myth, wellspring of Roman culture, Peace, or Eirēnē, was one of the threefold goddesses known as the Hōrai, or Hours. In their earliest incarnation, as recorded by the epic poet Hesiod in his Theogony, Eirēnē was the sister of Order (‘Eunomia’) and Justice (‘Dikē’). When the Hōrai later evolved into the classical Seasons – mythical personifications of our spring, summer, autumn and winter – the sisters became synonymous with growth, fertility and the cyclical passage of time.

It is a montage that speaks as much of Rome under Augustus’ leadership as of nature’s behaviour

If the sculpture of Peace and her entourage is indeed a depiction of the natural world governed by the seasons, then it is not typical of its time. Romans had become accustomed to seeing stereotyped images of the mythical seasons, especially in mosaics, as female deities, usually four in number and identified by conventional motifs. The Peace panel, however, presents a symphony of seasonal reference-points. Peace herself is portrayed here as a ‘goddess for all seasons’. Her setting within a firmament of heavenly and earthly elements enforces the notion of Augustus as ‘lord of the seasons’. Her sculpted attributes consist of a garland of flowers and leaves; a backdrop of poppies and grain; twin infants in her embrace, one seated on her knee, the other at her right hip, and both reaching for her breasts; a cow and a sheep at her feet, awaiting sacrifice; flowers and fruit, such as the apple, grape and pomegranate, also on her lap. A strong sense of fertility pervades the scene. The goddess’ bosom overhangs the infants and promises sustenance on demand. Elsewhere carved into the tableau are motifs of the winds, rain, stars, land and sea. One of the infants, on his mother’s left knee, offers her a piece of fruit, echoing the gesture of the infant Wealth (Ploutos) to his mother Peace (Eirēnē) in the free-standing 4th-century BCE sculpture by the Greek sculptor Kephisodotos. One is also reminded of the foundation myth of Rome and the wolf-suckled twins, Romulus and Remus.

Relief sculpture of Pax and attendant goddesses. SE panel, Altar of Peace (c9 BCE), Rome. Courtesy Wikipedia

Eirēnē (Peace) Bearing Plutus (Wealth). Roman copy after a Greek votive statue by Kephisodotos (c370 BCE) which stood on the agora in Athens. Courtesy Wikipedia

The Pax-Eirēnē scene on the Altar of Peace does not delineate the role and function of the seasons as autonomous beings, however. It is a montage that speaks as much of Rome under Augustus’ leadership as of nature’s behaviour. This was a message of infinite subtlety. Take the animal mounts upon which Peace’s sisters are seated. A swan appears to the left and a sea serpent to the right, the goddesses riding them with breasts bared and hair in wreaths. Tradition has it that they conveyed Augustan dominion by land and sea, terra marique. The battle of Actium in 31 BCE – in which Augustus, in his pre-imperial guise as Octavian, vanquished his last rival Mark Antony – had been a combined operation that harnessed land and sea forces. Peace juxtaposed with these two creatures captures the global nature of Roman hegemony under Augustus.

There may also be further, cosmic meanings. Combined with the image of the Maiden (‘Virgo’) and the twins (‘Gemini’), the swan and the sea-monster begin to look like symbols of constellations that have their domains in the four compass points of the night sky. Cycnus, the Swan, accounted for the northern hemisphere; Cetus, the Sea-monster, the southern; and Gemini and Virgo aligned with the ecliptic, shuttling east-west along the celestial axis as the year progressed. More significant still, their risings were seasonal, with Cycnus ascendant in the summer, Cetus in autumn, Gemini in the winter and Virgo in the spring. The closer we look, the more we find images redolent of nature in harmony and, by implication, a world now subject to the benign order of Augustus’ Rome.

The mission of Augustus to embed his position as emperor was firmly endorsed in the literary field, too. Contemporary writers conveyed the transition of Augustus from mere protégé of Julius Caesar, via successive settlements with the senate and renewals of his imperial mandate, to near-godlike status, a ‘mediator between men and gods’, as Zanker calls him. Virgil, in the dedicatory prologue to his poem the Georgics, begged the new Caesar to bestow approval on his masterpiece, certain that this ‘giver of increase’ would eventually take his place among the gods. Virgil’s poem dates to the beginning of the Augustan ascendancy following the turbulent period of civil war after 44 BCE, the year of Julius Caesar’s assassination.

Another of the greatest of the Augustan poets was Virgil’s contemporary Horace, born in 65 BCE, and a client, like Virgil, of the emperor’s senior political adviser, Maecenas. Most famous for his four books of Odes, Horace assigned Augustus the epithet divus (divine) and imagined him as an earthly ‘Jove the thunderer’, an example of the cultural shift away from the factional conflict of republican politics towards a golden age of common, imperial purpose. Horace’s later, laureate-style hymn in honour of the 10th anniversary of Augustus’ first constitutional settlement with the Senate expressed an Augustan ideal of convergence between the processes of nature and time. Growth was a fundamental aspiration of the Augustan state, as much as it is for governments today, but, for Horace and his milieu, this was more in the sense of natural abundance and ecological plenty. In one stanza, he expresses a prayer for the land, with an environmental flavour much in keeping with the sculptural depiction of Pax. Of the seasonal procession of birth, ripening and winter’s gift of rain, Horace wrote:

Let our land, teeming with crops and cattle,

Endow Ceres with a crown of ears of corn,

Let health-giving rain and the winds of Jove

Nourish all new life.

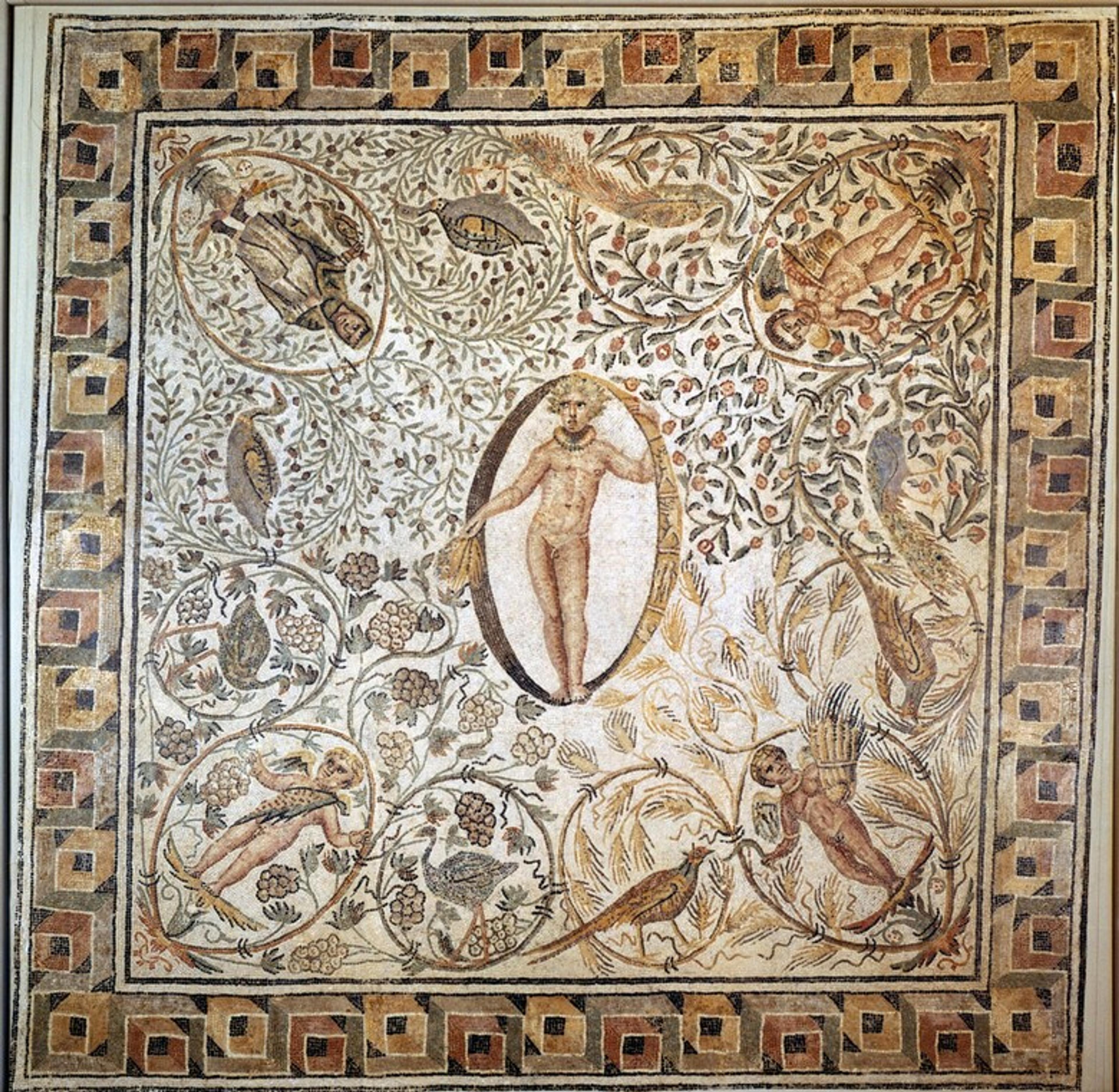

Even these life-giving processes, Horace explains, will benefit from stability after the chaos of civil war. Just as Horace had hymned the praises of the new regime in his Roman Odes, peppering his poetry with motifs from the natural and supernatural worlds denoting growth and prosperity, so the Altar of Peace seems to have had a similar function. The workings of nature and their cyclical character were understood and appreciated by the Romans. The numerous volumes written about farming and horticulture and the range of depictions on wall paintings and in mosaics of the natural world prove this. The frequent occurrence of birds, fish, nymphs and the seasons in visual arts primarily expressed the opulence of their owners. In the civic domain, however, nature and time appear to have been open to political manipulation by expert propagandists like Augustus and Maecenas.

It was the Hōrai, not Zeus the Cloud-gatherer, who cleared clouds away

Although the roots of the seasons in Roman art and literature are Greek, evocations of them by such early Greek poets as Homer, Hesiod and Pindar are quite different in tone and import. One can posit a notional identity of the Hōrai from their appearance in Greek mythology and in other authors. Their mother was Themis, goddess of order and propriety in human affairs, consort of Zeus. They were sisters of the Fates and half-sisters of the Graces, representing something of the qualities of each of these. In archaic and early classical vase painting they are shown attending important mythical events. They accompany their mother to the wedding of mythical Peleus and Thetis, parents-to-be of the greatest Greek hero, Achilles. Their physical appearance is often commented on, and other goddesses appreciate their taste and attention to finery.

Pindar refers to the Hōrai as ‘many-flowered’ and ‘purple-robed’, while one of the Homeric Hymns describes them as beautifying the goddess Aphrodite by deftly placing a golden coronet upon her head and decorating her with all manner of heavenly jewellery, including floral pendants and golden chains. According to Hesiod, they crown the head of Pandora with a floral garland shortly after her birth. Homer reports that the Hōrai are charged with dispelling the clouds shrouding the gates of Olympus when major deities are summoned or have an issue they want to take up with Zeus. But they prefer to be out of the torrid debating chamber of the palace itself and are heavy at heart when there is domestic discord – which there frequently was. So far, so superficial. Yet the notion of a relationship between the seasons with the elements and the wider firmament (their heavenly abode) was already visible. It was the Hōrai, not Zeus the Cloud-gatherer, who cleared clouds away.

Pindar, poet of the Olympic athletes and their victories, treated the Horai with the greatest respect. When it came to those competitors who had triumphed, and their communities, Pindar often attributed their best qualities to one of the three goddesses. On the victory of a certain Xenophon in the stadion and pentathlon events at the Isthmian games in Corinth in 464 BCE, he celebrated the virtues of the host city and Xenophon’s birthplace:

For there Order lives, and her sister Justice, cornerstone of cities,

And their sibling Peace, guardian of men’s riches

– the golden offspring of Themis the wise.

Corinth’s seeming ability to blend and embody the qualities of the Hōrai was considered a great virtue. Morally, Pindar goes on to say, the Hōrai were powerful deterrents to the overweening arrogance of mankind, for they kept ‘Hubris’ at bay, she who was the mother of ‘pushy-mouthed Excess’.

During the Hellenistic period, advances in mathematics and astronomy enabled a remarkable transition. From nebulous personifications as C-list celebrities at high-profile mythical events, the Hōrai metamorphosed into deities who actively presided over changes in nature at specific times of the year. The iconography of the Hōrai proceeded towards increasingly sophisticated representations in mosaics, sculptures and other artefacts throughout the Hellenised and later Roman world. Why did this transformation take place and how might this have shaped the seasons’ portrayal on the Altar of Peace?

Alexandrian scientists had defined the timings of the equinoxes and solstices so that the year’s seasonal phases could be calculated with greater precision. This in turn informed the practice of farmers who, since the time of Hesiod, had grappled with the correct timing of fundamental processes such as ploughing, sowing and harvesting. Poets such as Lucretius and Virgil versified this new science so that it shaped the elite’s perception of the countryside, and the workings of nature. Their work combined linguistic artistry with complex scientific and philosophical themes. Lucretius in particular integrated Epicurean science into his lyrical evocations of nature in a way that seems alien to the modern ear:

Why do we see the rose ripen in spring?

Why the corn in the summer and the vine too, when coaxed by autumn?

It has to be because, just then,

When, on cue, plant seeds have coalesced,

Nature’s creations reveal their true selves,

And, given the right season,

The teeming earth sends tender shoots up from dark to light.

For the Epicureans, nature, rather than the gods, drove the motion of the seasons and turned the years.

Olives too symbolised the season, as they were the last fruits of the year to be plucked

By now, the attributes of the Hōrai in the Roman visual arts had become codified. A representative sculpted image of Autumn has her luxuriating in the plentiful produce of her season. The goddess is clad in a tunic and mantle, displaying, in languid pose, a fulsome bunch of grapes. In her left hand she appears to caress a vine branch, full of the promise of yet more fruit in the future. Her headgear appears to be a conflation of vine leaf, grape and well-groomed tresses of hair.

Personification of Autumn (2nd century). From a Roman villa and courtesy Chiaramonti Museum, Vatican City

A mosaic from La Chebba in North Africa depicted Winter crowned with reeds and encircled by sprays of olive branch. Elsewhere, winter’s fauna were represented by ducks, often suspended from a pole carried along by a farmhand returning from the day’s hunt. Olives too symbolised the season, as they were the last fruits of the year to be plucked. The tree’s foliage might appear in garlands and its fruit in baskets brimful from the recent harvest. At Djebel Oust, also in North Africa, Spring is shown holding a basket of roses and wearing a chaplet of rose flowers. She is captured delicately weaving a further rose into her hair, while clothed in a richly bordered white tunic.

The Triumph of Neptune. Mosaic from La Chebba. Bardo Museum, Tunisia. Courtesy Wikipedia

An animal often associated with the Spring was the goat or kid. Mosaic depictions tended to focus on everyday items corresponding to the time of year, such as a shepherd’s crook, baskets of cheese, or pails of milk.

Mosaic of the Four Seasons (c238 BCE), Haidra, Tunisia. Now displayed as a wall hanging in the entrance to the Delegates’ North Lounge at the UN Headquarters in New York City. Photo by UN Photo/Lois Conner

To ancient visitors to the Altar of Peace, its hallowed imagery and sacred function must have inspired wonder and civic pride in equal measure. A stroll around the neighbouring dial plate of the solarium must have been equally exhilarating. It would have demonstrated that Augustus had achieved his mission to conquer Rome’s enemies and bring about peace, answering the poets’ prayers. More than that, he had done so in harmony with the domain of Peace, that is, the natural world. He had elevated Rome’s global standing to the level of time itself.

There is strong evidence, as we have seen, of an astronomical alignment between the solarium Augusti, the monumental timepiece, and the Altar of Peace, evident at the key milestones of the solstices and equinoxes. Even more symbolically, however, the gnomon cast its shadow on the Altar’s entrance precisely on the date of the autumn equinox, 23 September – by a quirk of fate, Augustus’ birthday. Even the emperor’s birth was now embedded into the chronology of nature, along with the seasons, the weather and the constellations. Crucially, the Altar of Peace, along with the solarium, suggested that their creator knew his grip on imperial power drew strength from even mightier forces – the seasons and Peace, nature and time.

Augustus’ conception of peace was far from our own. Augustan pax meant peace on his terms. No amount of propagandist imagery can disguise the underlying realpolitik of pax Augusta. But the agrarian society of ancient Rome was conscious of the difference between years of good sowings, good harvests, rich vintages. Lower strata lived on the margins of plenty and poverty, life and death. They would have been highly receptive to the Augustan promise of control over the forces on which so many of their lives depended. The mythological Hōrai offered people of the classical world certainty, a comforting predictability. Ever-vigilant, according to Pindar, for excess or hubris, the Hōrai on the altar panel embodied the quiet, fruitful orderliness to which the emperor aspired.

The Altar of Peace expressed a doctrine of harmony with nature, one that acknowledged the implacability of the seasons and the need for humility before the forces of nature and time. Seasons may change their identity, as they did in classical myth and iconography, or even their behaviour, as in the context of modern climate change, but no-one can stop their cyclical dance. The divine Augustus recognised this, willing to acknowledge his accountability to the (super)natural. There may be a lesson there.