It’s around 200 CE, in Ephesus, an Aegean city of Greek roots, now a major hub of the Roman Empire. Meandering down marble-paved Curetes Street, a dweller is lost in the bustle of the town, procuring produce and wares in shops tucked beneath the colonnades, attending the public baths – even a conveniently placed brothel. It all plays out alongside merchants from across the Mediterranean, who disembark their ships to transport cargos and conduct business in the great depot between West and East. They make their way past the shrine to the emperor Hadrian and the nymphaeum of the emperor Trajan, bold reminders that the Ephesians, in their prosperity, are now part of the realm in faraway Rome. And there, culminating at the end of this lively thoroughfare at a slight angle, as though gradually revealing itself, lies a theatrical marble-clad façade of elegant Corinthian columns, exquisite reliefs and wordy inscriptions. Up a short flight of stairs, flanked by statues, three large doors offer a glimpse into a single large room, colonnaded and high-ceilinged. Thousands of scrolls are carefully stacked into rectangular recesses in the walls. The doors to the towering Library of Celsus are flung wide open: anyone can enter this shrine to the written word.

The scene is millennia old, but hardly alien to modern times. Libraries have, through history, represented the ultimate repository of information and knowledge, and produced some of the most spectacular architecture in the Western world and beyond. Today’s libraries are a direct legacy of the Roman impulse to transcend practicality and invest arenas of knowledge with a sense of scale akin to that of churches – temples to a different creed – with their imposing porticoes and columns, their elaborate ornaments and staircases, their rows of desks and lofty shelves.

Yet a library cannot be reduced to the mere embodiment of universal education. The philosopher Michel Foucault once asserted that ‘power and knowledge directly imply one another’ – one cannot exist without the other. Where libraries have been designated as public, free and accessible to all, there has always existed the risk of echo chambers with curated contents and truths.

The institution of the public library goes further back than imperial Rome, of course. During the earlier Roman Republic (509-27 BCE), libraries were a private affair, concealed in the properties of the educated elite and off-limits to the masses. They were overseen by a vir magnus (great man), the owner of the house, who would open his collection to his amici (friends), providing an intimate atmosphere for intellectual exchange and cultural influence and posturing.

In its later years, the Roman Republic was beset by a series of cataclysmic civil wars and political showdowns that sent it hurtling towards one-man rule. The Republic, with its imperfect checks and balances on political power, had failed; but to the Roman people, defined by their aversion to monarchism and the conviction of liberty, it was inviolable. The first emperor, Octavian, found himself navigating a careful balancing act of titles and epithets without ever assuming himself as Rex (king): from Princeps Civitatis (first citizen) to primus inter pares (first among equals), all with connotations of authority but not monarchical supremacy. He would settle on Augustus (the venerable one) as his official title. The end of the Roman Republic was never announced – despotism prevailed in the superficial likeness of the Republic.

Amid this upheaval, the masses were manipulated with imperial cults and vanity projects and placated with bread and circuses. But still there remained a class of educated Republican aristocracy whose raw memories and ambitions had to be reined in. Hoping to resonate with the disaffected Roman public, Julius Caesar had already intended ‘to make as large a collection as possible of works in the Greek and Latin languages, for the public use,’ as the Roman historian Suetonius wrote. Caesar was ultimately beaten to the task by a soldier and politician named Gaius Asinius Pollio, who, by 28 BCE – just a year before Octavian became the Emperor Augustus – used his war plunder to fund Rome’s very first ‘public’ library in the Atrium Libertatis, Rome’s census record building.

Augustus understood his gesture was laden with symbolic, even revolutionary, significance

We can be sure that Pollio was watching then-Octavian closely as his power intensified; indeed, right after becoming Augustus, the first emperor opened his own public library within the Temple of Apollo on Palatine Hill in Rome. This cannot be a coincidence. Pollio, a member of the Republican senatorial order, had snatched credit for gifting the Roman public the first public collection of books.

From then on, Augustus had no reason to be diplomatic. He probably populated his growing collections with the books confiscated from the heirs of the generals he defeated in the late Republican wars. If the emperor sought submission, he had to subjugate minds and ideas.

An imperial tradition had begun. When Augustus opened his first library, he was, in effect, usurping the role of a Republican patronus (patron) of culture and knowledge, except on a much larger scale. Opening his large libraries to an ever-wider public, he was a vir magnus writ large.

The perception of the imperial libraries as ‘public’ resources stood in glaring contrast to the closed collections that continued to operate in private properties. The Latin verb publicare (to make public/release) and its cognates appear throughout Roman literature in reference to these new libraries. The poet Ovid, banished in 8 CE by Augustus to distant Tomis on the Black Sea, marvelled at his visit to the Palatine library, where ‘all that men of old and new times thought, with learned minds, is open to inspection by the reader’.

Augustus understood his gesture was laden with symbolic, even revolutionary, significance. He was offering the Roman people access to knowledge that had once been confined by the Republican elite behind closed doors. And as though to accentuate this sense that the library was the emperor’s private space – and its contents his personal property – in which all others were welcome guests, Augustus’ private Palatine residence was connected to the Temple of Apollo and its library by special access. The library itself was an ode to imperial achievement – the atmosphere of the temple seems to have leaked inside. Colonnades resembled those of Latin and Greek libraries that came before; statues alternated with exotic pillars; and its walls were adorned by portraits of famous authors.

The earliest known reference to Rome’s public libraries was made by the poet Horace in 20 BCE. And in contrast to Ovid’s sensation of cultural apogee, Horace’s words are fraught with warning:

What, pray, is Celsus doing? He was warned, and must often be warned to search for home treasures, and to shrink from touching the writings which Apollo on the Palatine has admitted: lest, if some day perchance the flock of birds come to reclaim their plumage, the poor crow, stripped of his stolen colours, awake laughter.

Glance through the poetic diction, and the implication is clear. The books of the Palatine library are compromised, ‘stripped’ of their substance. We sense a suspicion that must have been widely held in elite circles – better to stick to the ‘home treasures’ of the old-school private collections; they were not yet tainted by the venom of despotism.

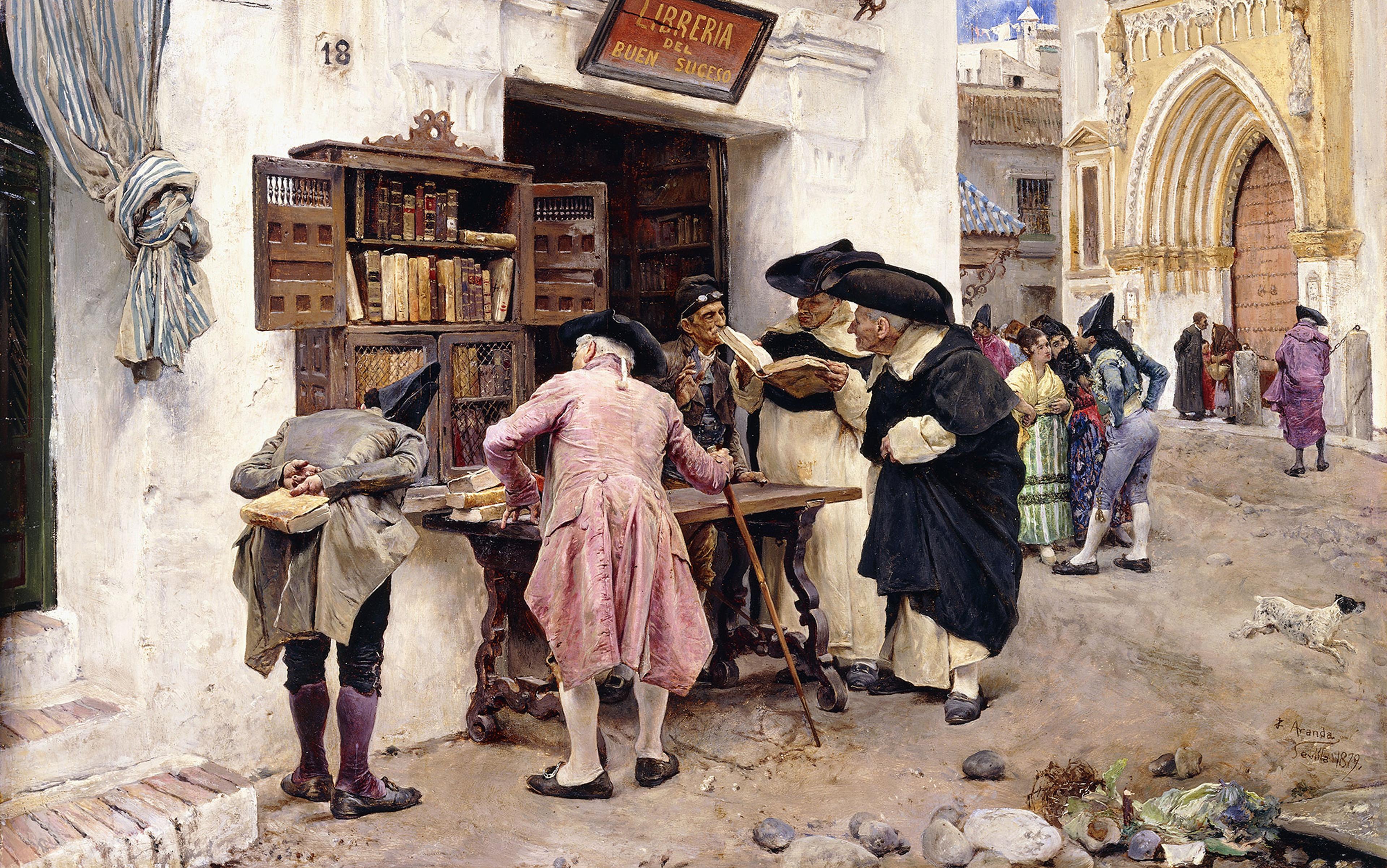

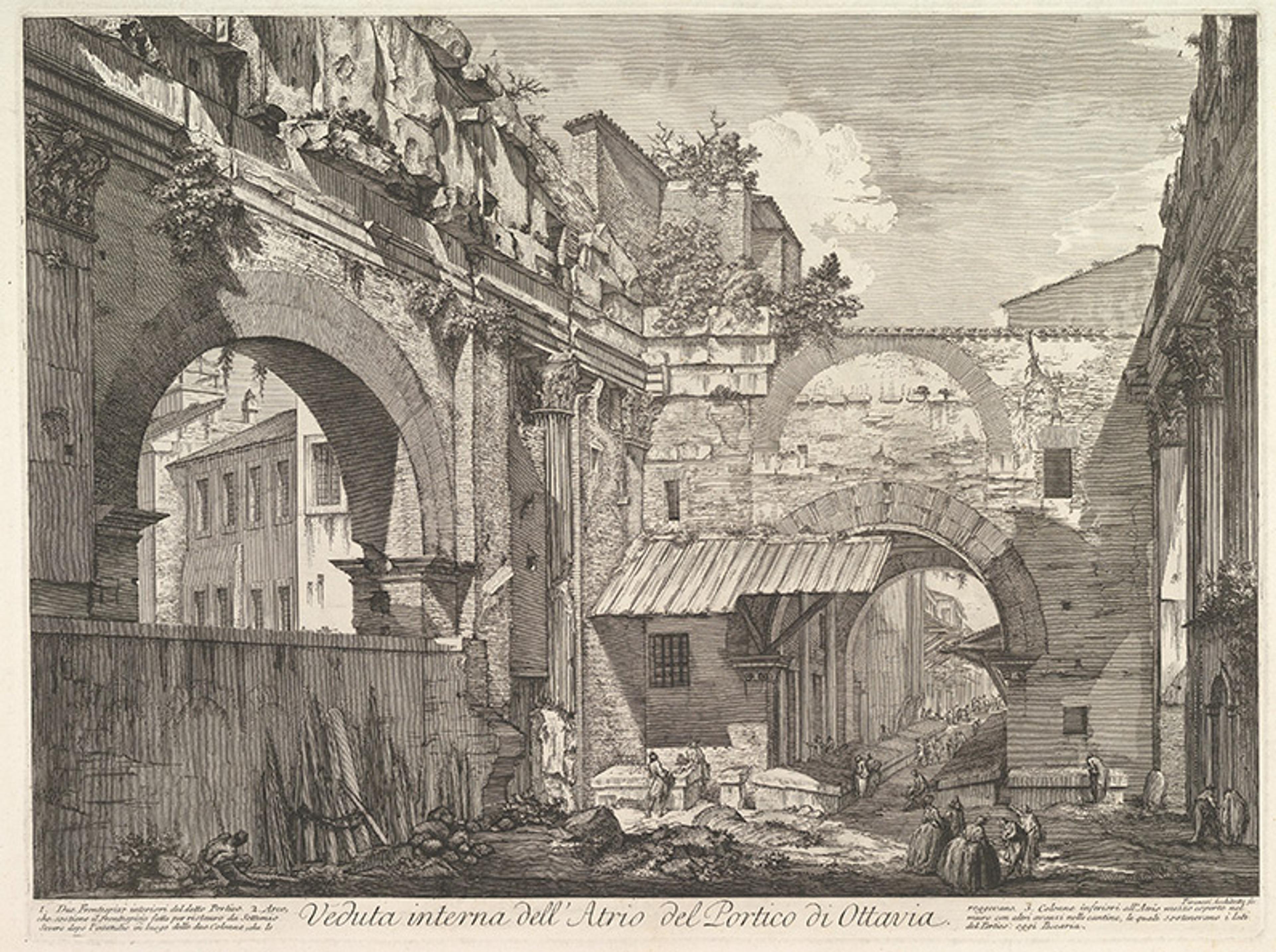

Internal View of the Atrium of the Portico of Octavia (1760) by Giovanni Piranesi. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

This wasn’t paranoid. In wrangling control of the elite’s intellectual world, Augustus was intrusive and possessive. To keep the growing number of collections, he appointed his own educated freedmen (manumitted slaves who remained legally and socially distinguished from freeborn Romans): Gaius Julius Hyginus, a polymath scholar and grammarian, took charge of the Palatine, while the library in the Porticus of Octavia was entrusted to the grammarian Gaius Maecenas Melissus. Forever beholden to their liberator and presumably unambitious, these were men Augustus could trust. Meanwhile, in a nod to their new inferior status, he seems to have cast most of the elite from their traditional domain. Only freeborn Pompeius Macer was left to ‘the arrangement of his libraries’, as far as we know.

‘Strict examination’ of library volumes was a euphemism for state censorship

Like any good autocrat, Augustus didn’t refrain from violent intimidation, and when it came to ensuring that the contents of his libraries aligned with imperial opinion, he need not have looked beyond his own playbook for inspiration. When the works of the orator/historian Titus Labienus and the rhetor Cassius Severus provoked his contempt, they were condemned to the eternal misfortune of damnatio memoriae, and their books were burned by order of the state. Not even potential sacrilege could thwart Augustus’ ire when he ‘committed to the flames’ more than 2,000 Greek and Latin prophetic volumes, preserving only the Sibylline oracles, though even those were subject to ‘strict examination’ before they could be placed within the Temple of Apollo. And he limited and suppressed publication of senatorial proceedings in the acta diurna, set up by Julius Caesar in public spaces throughout the city as a sort of ‘daily report’; though of course, it was prudent to maintain the acta themselves as an excellent means of propaganda.

We can sense the typical behaviour of an absolutist ruler soothing his anxieties amid the fragility of his new regime – but this was also a calculated attack, a forewarning to anyone who could write, and anyone who, even if indirectly, might cause offence. ‘Strict examination’, the imperial biographer Suetonius surely perceived when he wrote it, was a euphemism for state censorship.

Horace suggested the insidious encroachment of imperial truth into the public libraries, but Ovid paid the price. Betrayed by ‘a poem and a mistake’ – with his Ars Amatoria allegedly considered too salacious for the prudish emperor and, more decisively, having found himself entangled at the wrong end of a succession conspiracy – the pitiful poet deplores in his Tristia that, at the Palatine, ‘the guard, from that house that commands the holy place, ordered me to go. I tried another temple, joined to a nearby theatre: that too couldn’t be entered by these feet. Nor did Liberty [ie, Atrium Libertatis] allow me in her temple…’ Ultimately, just ‘a short and plain letter to Pompeius Macer’ was enough for Augustus to forbid the publication in his collections of any specific writings – even those composed by the revered Julius Caesar in his youth, including such trivialities as his take on the Oedipus tragedy.

And just as examination of the works implied censorship, with the libraries open for gatherings, participation implied supervision – and the chance to sway the crowd. Augustus presented himself to attendees not as a dreaded force but as a generous and genuinely involved patron of the intellectual community. Indeed, writes Suetonius, he gave ‘every encouragement to the men of talent of his own age, listening with courtesy and patience to their readings’ – yet even then, the easily affronted autocrat could not help but take ‘offence at being made the subject of any composition except in serious earnest and by the most eminent writers.’

As the imperial order consolidated itself, the early emperors became more secure in their authority. The logic of appointing freedmen almost exclusively to keep the collections appears to have persisted with Augustus’ successor Tiberius (reign 14-37 CE), though this became less absolute, and acts of censorship, like book burning, declined in frequency. Still, Tiberius was spooked by the Sibyl foretelling ‘civil strife upon Rome’. In the words of the Roman historian Cassius Dio, Tiberius denounced the verses as ‘spurious and made an investigation of all the books containing prophecies, rejecting some as worthless and retaining others as genuine.’

For the astute observer at the time, it would have made for a sombre realisation that imperial policy could be inconsistent and viciously irrational – Virgil’s Aeneid, a foundational epic claiming the destiny of Augustus’ reign, had once served to extol and immortalise the legacy of the first emperor, and his work and image were once received with great approval into the imperial collections. Yet Caligula (reign 37-41 CE) removed the writings and the busts of Virgil, who he said was talentless, and Titus Livius, who was dismissed as careless and verbose. These libraries were not just handy repositories for all literate citizens to enjoy – they presented to the emperors an opportunity to contrive a formative instrument of state opinion and policy, curated to reflect what they wanted public knowledge and truth to be.

Eventually, maintenance of public collections became a matter of procedure. When he was roaming about the Palatine one day, Claudius (reign 41-54 CE) is said to have caught the historian Nonianus and his audience off-guard as he recited his work (presumably in the library) when ‘he suddenly joined the company to every one’s surprise’ – a surprise that was, no doubt, laced with honour as much as some trepidation. Intellectual interest and expertise were not even prerequisite for such imperial obligations. The attempt by Domitian (reign 81-96 CE) to restore the burnt-down library built by Tiberius in the Temple of Augustus ‘at a vast expense’ – hurriedly sending his agents to collect manuscripts from all parts, and even sending scribes to Alexandria – is impressive. But this is the same Domitian who also allegedly never bothered himself with ‘the trouble of reading history or poetry, or of employing his pen even for private purposes’. So what if the emperor, as patron of the intellectual community, was not intellectually inclined himself? His job was one of maintenance.

The rooms themselves were a luxuriant, polychrome feast of Egyptian granite and Anatolian marble

That maintenance could not escape the imperial Roman tendency to brazen ostentation and excess. A number of libraries sprung up in the capital – Augustus’ collections in the Palatine and the Porticus of Octavia (perhaps built by Augustus’ sister Octavia herself), Tiberius’ libraries in the Temple of Augustus and in the imperial palace on the Palatine, and Vespasian’s (reign 69-79 CE) collection located within or attached to the Temple of Peace. There is even one associated, if tenuously, with the Baths of Agrippa complex near the Pantheon. Even beyond Rome, where in the absence of emperors provincial politicians were handed the prerogative of building institutions, the emphatic Hellenophile Hadrian (reign 117-138 CE) wished to imprint his legacy on the cradle of philosophy (and, almost sardonically, democracy) itself, and constructed his own library in Athens. It was later eulogised by the Greek geographer Pausanias for its ‘hundred pillars of Phrygian marble’ and its rooms ‘adorned with a gilded roof and alabaster stone, as well as with statues and paintings.’ Only later, as though an afterthought, does he mention that ‘in them there are books’.

Perhaps at the pinnacle of the imperial project was the Ulpian Library, inserted prominently into the Forum of Trajan in the centre of Rome by the emperor himself in 114 CE. It was distinguished by its twin Latin and Greek book collections, located directly opposite one another, with the colossal 38-metre-high Column of Trajan slipped between them. The separate collections were dominated by their single, high-ceilinged rooms, and flooded with desks and Corinthian columns that adorned their front porticoes and flanked the statues and cabinet niches. The rooms themselves were a luxuriant, polychrome feast of Egyptian granite, Numidian golden/purple giallo antico and Anatolian marble, all hauled on ships from across the Mediterranean and up the River Tiber at what must have been considerable expense.

This overwhelming sensory experience was a reflection of the metropolis itself – as magisterial as it was chaotic. And with space at a premium in this dense, unplanned urban fabric, the collections were incorporated as smaller components of other larger complexes of temples, porticoes and forums, concentrated in the ‘historic centre’ of the city rather than dispersed, creating a sort of clustering effect. Rather than drown out the libraries, the association with contexts of religious and civic importance only enhanced their importance in Rome’s sea of monuments – just like that legendary epitome of libraries across the Mediterranean, the Great Library of Alexandria, itself a branch of the Musaeum complex.

Reviewing the elaborate masterplan, we cannot ignore one glaring fact: the overwhelming majority of people in the Roman world were illiterate. It’s hard to picture masses of urban dwellers frequenting and availing themselves of these collections. Should we therefore dismiss the level of architectural effort and investment that supported the establishment of these grand ‘public’ libraries as a bizarre waste?

They seem even more gratuitous when we unravel some of the architectural impracticalities. The esteemed architect Vitruvius had long ago posited that a library should acquire an eastward orientation to provide morning light and good natural protection against damp – however, in the small town of Timgad (in modern Algeria), the architect of the Library of Rogatianus instead opted to position the public entrance to its single book room facing west onto the settlement’s principal thoroughfare rather than eastward onto an unimpressive backstreet. And though housing the scrolls in a single, large book room would have heightened the sense of accessibility, this choice also exposed them to potential ill-doers and thieves, as well as damp, that could have much more easily been avoided by smaller upper-floor accommodation.

Yet futility was not a flaw: if the focus was on appearances and exhibition, the rules of preservation would not be worth much.

It did not matter if the masses could not read any of it

In a world of mass, normalised illiteracy, the notion of a ‘public’ library would have carried different connotations – and, as today, we can imagine that libraries must have been public in the most literal sense to varying extents. If collections such as the Ulpian Library or those of Ephesus and Timgad, with their book rooms opening right onto the public space in a direct embrace of passersby, suggest an emphasis on walk-in accessibility, those located within temples and palace precincts, even if supposedly public, would surely have been restricted for random passersby. Perhaps these operated as ‘public’ repositories, accessible to those of interest on an appointment basis, not too dissimilar from many contemporary collections.

Ultimately, Rome’s ‘public’ libraries were monuments parading as civic institutions, a conspicuous display of imperial benevolence to the Roman people and the victory of the new order – one in which the emperors ostensibly endorsed free enquiry, and where knowledge was liberated from the shackles of the Republican aristocracy. If Asinius Pollio was the one who ‘first by founding a library made works of genius the property of the public [rem publicam]’, it was Augustus and his successors who instilled an ideology of the public ownership of knowledge.

And it did not matter if the masses could not read any of it – they could satisfy themselves with the illusion that masked yet another mechanism of autocratic control. Democratic access to the written word was never the intention.

The integrity of the library, even in mature, modern democracies, cannot be taken for granted. Just consider the revelation of the American Library Association that, in 2022, in the United States, there were 1,269 documented demands for the censorship of 2,571 titles in school and public libraries, the vast majority of which were works by or concerning the LGBTQIA+ community and people of colour. According to a report from PEN America, in the school year 2021-22, book bans ‘occurred in 138 school districts in 32 states. These districts represent 5,049 schools with a combined enrolment of nearly 4 million students.’ In the UK too, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals has voiced increasing concerns following a survey in 2022 that revealed a rising incidence of censorship requests. Libraries are easily malleable and inherently vulnerable to conflicts of power, ideological chasms and thought control – the Romans themselves taught us this, and sometimes it seems like not much has changed.

In a distant echo from the past, as though appealing to our apprehensions, the imperial historian Tacitus, introducing his Histories, betrays an envy of his past Republican counterparts – once power was ‘concentrated in the hands of one man’, he observes, ‘historical truth was impaired in many ways.’ Wistfully, he longs for the past ‘rare good fortune of an age in which we may feel what we wish and may say what we feel.’