The young man was having sex with his dog. In fact, he’d lost his virginity to it. Their relationship was still very good; the dog didn’t seem to mind at all. But the man’s conscience was eating at him. Was he acting immorally?

In search of sage counsel, he sent an email to David Pizarro, who teaches a class on moral psychology at Cornell University in New York. ‘I thought he was just pulling my leg,’ said Pizarro. He sent the man a link to an article about bestiality, and thought that would be the end of it. But the man responded with more questions. ‘I realised this kid was pretty serious.’

Although Pizarro is a leader in his field, he struggled to craft an answer. ‘What I ended up responding was: “I might not say this is a moral violation. But in our society you’re going to have to deal with all manner of people believing that your behaviour is odd, because it is odd. It’s not something anybody likes to hear about.” And I said: “Would you want your daughter to date someone who has been having sex with their dog? And the answer is no. And this is critical: you don’t have animals writing essays about how they’ve been mistreated because of their love of human beings. I would get help for this.”’

In essence, Pizarro was saying that the man’s behaviour was weird, concerning and distressing, but he wasn’t willing to condemn it. If that doesn’t sit well with you, you’re probably sickened by the very image of someone having sex with a dog. But was the man acting immorally? At least by the man’s own account, the dog wasn’t being harmed.

If you’re struggling to put your finger on why exactly the man’s behaviour seems wrong, psychologists have a term for your confused state of mind. You’re morally dumbfounded.

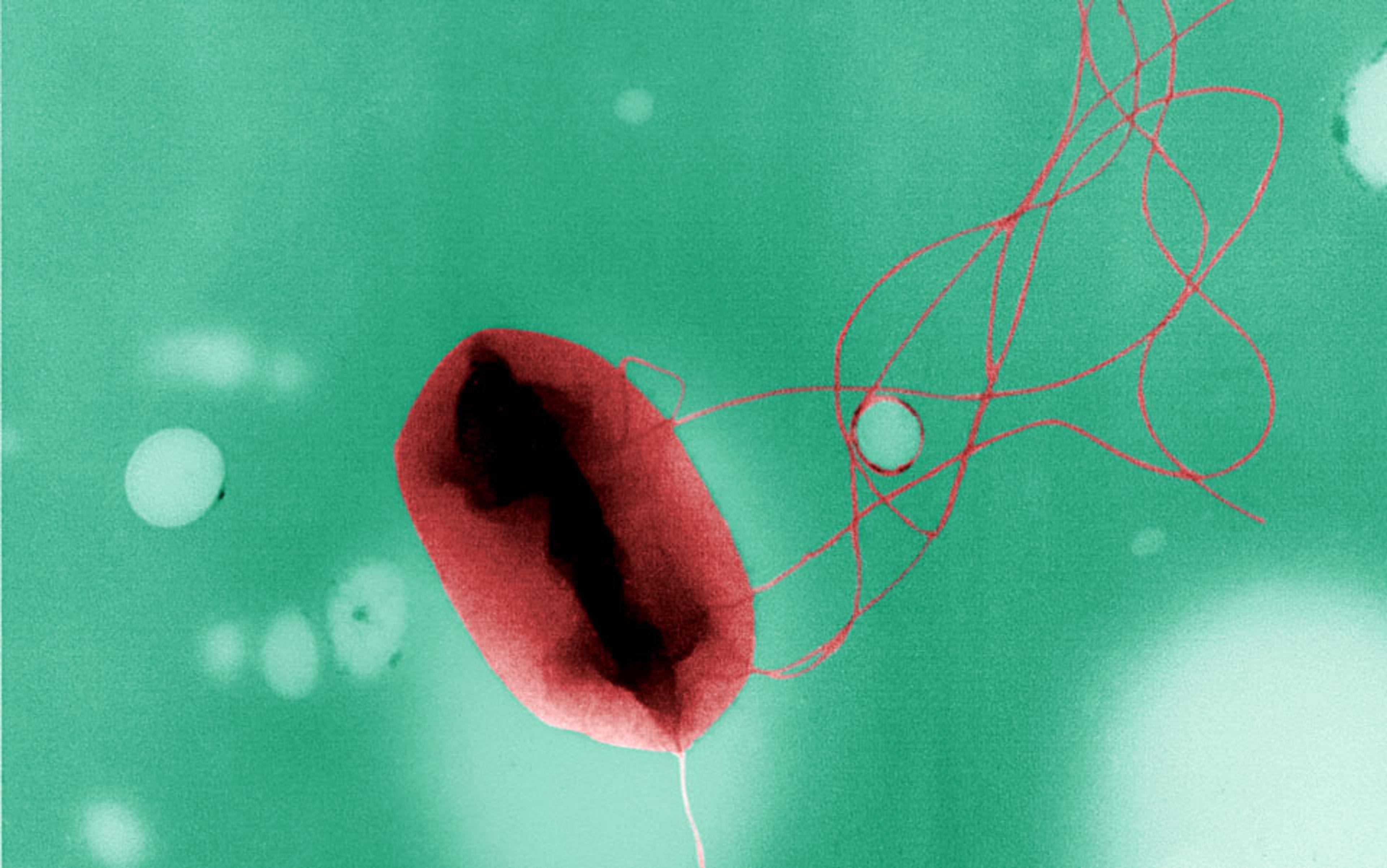

A ballooning body of research by Pizarro and others shows that moral judgments are not always the product of careful deliberation. Sometimes we feel an action is wrong even if we can’t point to an injured party. We make snap decisions and then – in the words of Jonathan Haidt, a social psychologist at New York University – ‘construct post-hoc justifications for those feelings’. This intuition, converging lines of research reveal, is informed by disgust, an emotion that most scientists believe evolved to keep us safe from parasites. Marked by cries of ‘Yuck!’ and ‘Ew!’, disgust makes us recoil in horror from faeces, bed bugs, leeches and anything else that might sicken us. Yet sometime deep in our past the same feeling that makes us cringe at touching a dead animal or gag at a rancid odour became embroiled in our most deeply held convictions – from ethics and religious values to political views.

Disgust’s key role in our moral intuitions is echoed in language: dirty deeds; slimy behaviour; a rotten scoundrel. Conversely, cleanliness is next to godliness. We seek spiritual purity. Corruption can contaminate us, so we shun the evil.

Pizarro has a deep distrust of using disgust as a moral compass. If people rely on it, he warns, it can lead them astray. Denouncing homosexuality on the grounds that it’s repugnant is a prime example of that danger, he argues. ‘I tell my class: as a heterosexual male, it’s not as if I won’t be disgusted if you show me pictures of certain sexual acts between two males. The task for me is to say: what the hell does this have to do with my ethical beliefs? I tell them, the thought of two very ugly people having sex also revolts me, but that does not lead me to consider legislating against ugly people having sex.’

The homeless are another group that people frequently speak ill of, probably because they, too, can trigger disgust alarms, making it easier for society to dehumanise them and find them guilty of crimes they didn’t commit. ‘My ethical duty is to make sure that this emotion doesn’t influence me in a way it might actually tread on someone’s humanity,’ Pizarro said.

He knows better than most the travails of not letting disgust seep into ethical judgments. He is so squeamish that he has to rely on his students to programme all the pictures of repulsive imagery used in his studies on moral reasoning. ‘It took just brute reasoning to shake myself of some of my attitudes,’ he said. ‘I consider it an intellectual achievement that I became liberalised about a lot of issues.’

The curse of being exceedingly easy to disgust has nonetheless been a benefit in his work: it has given him keen insights into how the emotion can guide moral thought.

If you’re skeptical that parasites have any bearing on your principles, consider this: our values actually change when there are infectious agents in our vicinity. In an experiment by Simone Schnall, a social psychologist at the University of Cambridge, students were asked to ponder morally questionable behaviour such as lying on a résumé, not returning a stolen wallet or, far more fraught, turning to cannibalism to survive a plane crash. Subjects seated at desks with food stains and chewed-up pens typically judged these transgressions as more egregious than students at spotless desks. Numerous other studies – using, unbeknown to the participants, imaginative disgust elicitors such as fart spray or the scent of vomit – have reported similar findings. Premarital sex, bribery, pornography, unethical journalism, marriage between first cousins: all become more reprehensible when subjects were disgusted.

participants exposed to a noxious odour were subsequently more likely to endorse biblical truth than those not subjected to the polluted air

The repulsed are also more likely to read evil intent into innocuous acts. In a trial conducted by Haidt and his graduate student Thalia Wheatley, hypnotic suggestion was employed to cue subjects to feel a wave of disgust when they came across the words take and often. Then the volunteers read a story about Dan, a student council president who was trying to line up topics for students and professors to discuss. It had no moral content. Yet subjects who got the version that contained the disgust-trigger words were more suspicious of Dan’s motives than controls who read a virtually identical story without the hypnotic cues. Explaining their distrust of Dan, participants offered rationalisations such as: ‘It just seems like he’s up to something’ and ‘Dan is a popularity-seeking snob.’

Harmless sex acts can similarly acquire immoral overtones if germs are foremost on your mind. When subjects in one of Pizarro’s studies were shown a sign recommending the use of hand wipes, they were harsher in their judgment of a girl who masturbated while clutching a teddy bear and a man who had sex in his grandmother’s bed while housesitting for her.

There’s a clear pattern to these findings, as an investigation by Mark Schaller and Damian Murray, psychologists at the University of British Columbia, reveals. People who are reminded of the threat of infectious disease are more inclined to espouse conventional values and express greater disdain for anyone who violates societal norms. Disease cues might even make us more favourably disposed toward religion. In one study, participants exposed to a noxious odour were subsequently more likely to endorse biblical truth than those not subjected to the polluted air.

When we’re worried about disease, it appears, we’re drawn not just to Mama’s cooking but also to her beliefs about the proper way to conduct ourselves – especially in the social arena. We place our faith in time-honoured practices probably because they seem like a safer bet when our survival is in jeopardy. Now’s not the time to be embracing a new, untested philosophy of life, whispers a voice in the back of your mind.

In light of these findings, Pizarro wondered if our political attitudes might shift when we’re feeling susceptible to disease. In collaboration with Erik Helzer at the Johns Hopkins Carey Business School in Baltimore, he came up with a clever strategy to test the idea. They positioned subjects either next to a hand-sanitiser station or where none was in sight, and asked about subjects’ views on various moral, fiscal and social issues. Those reminded of the dangers of infection expressed more conservative opinions.

Intriguing as these results are, they should be interpreted with caution. When we’re called upon to render moral judgments in real life, we have more information to go by than in laboratory settings – among other things, people’s demeanour, how they generally comport themselves, mitigating circumstances, and so forth. ‘There are a lot of influences on moral judgment and disgust is only one of them,’ emphasised Pizarro. In the more complicated world of everyday life, snap decisions based on visceral disgust are no doubt often later tempered by logic and reason, leading us to modify our initial assessment of an infraction or even conclude it constitutes no breach of ethics. What’s more, disgust acts on a person’s already well-developed system of values. A filthy desk or a whiff of a foul scent does not turn sexual libertines into prudes, atheists into religious zealots, or renegades into conformists. ‘The shift in attitudes is temporary and modest in size,’ stressed Pizarro. ‘If you want to influence people’s attitudes, there are probably much more powerful ways to do it.’

Those caveats might have bearing on the outcome of a recent study he did to test whether a particularly robust laboratory finding – the fomenting of anti-gay sentiment in response to disease cues – held up in the real world. Working in collaboration with Yoel Inbar at the University of Toronto and colleagues, his team conducted an online survey of Americans’ attitudes toward homosexuality as concerns about the Ebola outbreak reached a fever pitch during the autumn of 2014.

Implicit views toward the group did indeed shift in a negative direction, the scientists found, but the effect was much smaller than they’d anticipated.

the readily revolted are more likely to hold stable political views at the conservative end of the spectrum

Maybe it was so weak, Pizarro theorised, because participants might not have been worrying about Ebola recently enough to when their opinions were actually tapped. In the lab, surveys are filled out within a few minutes of exposure to a noxious odour. But Pizarro does not discount an alternative possibility – namely, that disgust elicitors amplify only existing prejudices. Societal attitudes toward gays have radically changed in the past few years, and this once-reviled group is now viewed more favourably. If that’s why the outbreak had such a puny effect on anti-gay sentiment, Pizarro said: ‘it would be really encouraging’.

However, being squeamish by temperament might have significant, long-lasting effects on your attitudes and beliefs. Pizarro and others have found that the readily revolted are more likely to hold stable political views at the conservative end of the spectrum. They tend to be hard on crime; against casual sex, abortion and gay rights; and authoritarian in orientation. They’re more inclined to think children should obey their elders without question, and they place greater emphasis on social cohesion and following convention. Though the evidence is not as strong, there are even hints that those prone to disgust are more likely to be fiscally conservative (against taxation and government spending programmes).

There’s a physiological angle to this story as well. When shown pictures of people eating worms and other revolting imagery, conservatives sweat more profusely than liberals (as measured by galvanic skin response). Their heightened reactivity, however, is not limited to disease-related dangers. Compared with liberals, they also react to loud noises with a more pronounced startle response. These twin observations might have direct bearing on a well-documented finding in political science: conservatives typically view the world to be a more threatening place than liberals. That, in turn, could influence their position on issues relevant to foreign policy. In addition to being more distrustful of foreigners, they might be more willing to use force. Next to liberals, conservatives certainly are more outspoken in their support of patriotism, a strong military, and the virtue of serving in the armed forces.

Looking at this evidence in total, you’d expect disgust sensitivity to predict voting behaviour. Indeed, it does – not perfectly, of course. Your upbringing, religious affiliation, income bracket and numerous other factors shape your ideology, too. But if we look at a large group of people, there’s a consistent trend in the data.

In a study of 237 Dutch citizens published in 2014, those who scored highest on an online test of disgust sensitivity were more likely than their less squeamish countrymen to vote for the socially conservative Freedom Party, which takes a strong position against immigration, is hostile toward Islam, emphasises the value of Dutch traditions over a multicultural ethos, and is skeptical towards the European Union. The Netherlands has 10 political parties whose positions on many issues cannot be neatly characterised as either liberal or conservative, so the researchers could not predict voting across the board, but they did find that subjects’ disgust sensitivity correlated with their political ideology in keeping with the pattern previously outlined.

A still larger online study yielded similar findings. Conducted by a team that included Pizarro, Haidt and Inbar, it involved 25,000 Americans who were surveyed at the time of the 2008 presidential election. Respondents who scored high on a measure of contagion anxiety were more likely to report that they intended to vote for John McCain (the more conservative candidate) than Barack Obama. What’s more, a state’s average level of contamination concern – calculated from the disgust-sensitivity scores of respondents from each state – predicted the share of the votes actually cast for McCain.

The researchers found the same correlation between disgust sensitivity and political ideology across 122 nations scattered around the globe – basically, all countries for which there was a sufficient number of respondents to permit statistical analysis. As the investigators wrote in the Journal of Social Psychological and Personality Science: ‘this strongly suggests’ that the ‘relationship is not a product of the unique characteristics of US (or, more broadly, Western democratic) political systems. Rather, it appears that disgust sensitivity is related to a conservatism across a wide variety of cultures, geographic regions and political systems.’

Not surprisingly, politicians have sought to harness the science of disgust to their own advantage. A noteworthy example is a novel ad campaign by Carl Paladino, a Tea Party activist, during the 2010 Republican gubernatorial primary race in New York. Days before the election, registered voters in his party opened their mailboxes to find brochures saturated with the scent of garbage bearing the message ‘Something Stinks in Albany’. The leaflet displayed photos of Democrats in the state who’d recently been dogged with scandal and characterised Paladino’s opponent, the former Representative Rick Lazio, as being ‘liberal’ and part of a government that allowed corruption to flourish. Whether the stinky mailers boosted votes for Paladino even slightly we’ll never know. But they don’t seem to have hurt him: he trounced Lazio by a whopping margin of 24 per cent.

More recently, Donald Trump bizarrely characterised Hillary Clinton’s extended bathroom break during a Democratic primary debate as ‘too disgusting’ to talk about, causing the crowd to erupt in laughter and applause.

A fear of germs does more than slant people’s religious and political views. It literally leads them to think of morality in black-and-white terms – a finding with disturbing ramifications for the criminal justice system. You’ve likely noted that fairy godmothers wear white and wicked witches black, and that the gun-toting heroes and villains in TV Westerns follow the same dress code. To the psychologists Gary D Sherman of Harvard and Gerald L Clore of the University of Virginia, who showed that we associate dark colours with filth and contagion, this seemingly trite observation raised an intriguing question: as a byproduct of being honed to spot contaminants, does the human mind actually encode black as sinful and white as virtuous?

To explore this possibility, they took advantage of a favourite brain-training game: the Stroop test. A typical challenge is to press a key the moment you see a word that spells out the name of a specific colour – say, yellow. If the letters of the word are coloured yellow, people perform the task faster than if the letters are coloured blue or another mismatching hue, indicating that the mind takes extra time to process information that conflicts with expectations.

In the researchers’ modified version of the test, volunteers were shown morally charged words such as crime, honesty, greed and saint in randomly alternating black or white type. The words flashed before them at a quick clip, and the challenge was to press a key only if the word had a negative moral connotation. Subjects were much faster at the task if a word associated with sin was in black, suggesting that connection was rapid and automatic. The opposite pairings evidently triggered confusion, slowing their speed.

In search of better evidence that participants’ bias might be a mental adaptation to reduce exposure to infection, the researchers took the experiment a step further. They primed subjects to think of unethical deeds by having them write about a sleazy lawyer, and then they ran them through the Stroop test again. This time participants were even quicker at linking black words to evil and white words to virtue – despite the fact that some of the words used during the trial (among them, gossip, duty and helping) were much more loosely related to morality. Since our minds tend to make snap decisions about germ threats to ensure our safety – indeed, some scientists liken it to a reflex – the researchers grew increasingly confident that the subjects were relying on moral intuition rather than the slower process of conscious reasoning.

If so, Sherman and Clore theorised, people who were the fastest to link white to morality and black to immorality would be more concerned about germs and cleanliness. To explore this hunch, all the participants were asked to evaluate the desirability of cleaning products and other consumer goods at the end of the trial. Just as they anticipated, those whose test results suggested that they might be germaphobic gave the most favourable ratings to cleaning products – especially items that were hygiene-related, such as soap and toothpaste.

Since the tendency to see black as bad is heightened when moral issues are foremost on our minds, a courtroom is exactly the place where one would expect the cognitive bias to be most pronounced – unsettling news for people of colour hoping for a fair trial. ‘The darkness-contamination-evil link probably doesn’t contribute as strongly to prejudice as the linking of ethnicity, poverty and crime,’ said Clore, ‘but it’s concerning because all these negative biases might have an additive effect, raising the odds that a person of colour will be found guilty or receive a harsher sentence.’

These and related studies raise an obvious question: how have parasites managed to insinuate themselves into our moral code? The wiring scheme of the brain, some scientists believe, holds the key to this mystery. Visceral disgust – that part of you that wants to scream ‘Yuck!’ when you see an overflowing toilet or think about eating cockroaches – typically engages the anterior insula, an ancient part of the brain that governs the vomiting response. Yet the very same part of the brain also fires up in revulsion when subjects are outraged by the cruel or unjust treatment of others. That’s not to say that visceral and moral disgust perfectly overlap in the brain, but they use enough of the same circuitry that the feelings they evoke may sometimes bleed together, warping judgment.

While there are shortcomings in the design of the neural hardware that supports our moral sentiments, there’s still much to admire about it. In one notable study by a group of psychiatrists and political scientists led by Christopher T Dawes of New York University, subjects had their brains imaged as they played games that required them to divide monetary gains among the group. The anterior insula was activated when a participant decided to forfeit his own earnings so as to reallocate money from players with the highest income to those with the lowest (dubbed the Robin Hood impulse). The anterior insula, other research has shown, also glows bright when a player feels that he has been made an unfair offer during an ultimatum game. In addition, it’s activated when a person chooses to punish selfish or greedy players.

These kinds of studies have led neuroscientists to characterise the anterior insula as a fountainhead of prosocial emotions. It is credited for giving rise to compassion, generosity and reciprocity or – if an individual harms others – remorse, shame and atonement. By no means, however, is the insula the only neural area involved in processing both visceral and moral disgust. Some scientists think that the greatest overlap in the two types of revulsion can occur in the amygdala, another ancient part of the brain.

Psychopaths are notorious for their lack of empathy, and typically have smaller than normal amygdalae and insulae, along with other areas involved in the processing of emotion. They are also less bothered than most by foul odours, faeces and bodily fluids, tolerating them – as one scientific article put it –‘with equanimity.’

People with Huntington’s disease – a hereditary disorder that causes neurological degeneration – are similar to psychopaths in having shrunken insulae. They, too, lack empathy, though they don’t exhibit the same predatory behaviour. Possibly owing to damage to additional circuits involved in disgust, however, the afflicted show no aversion to contaminants – for example, they think nothing of picking up faeces with their bare hands.

Our ancestors might have been more concerned about hygiene and sanitation than commonly assumed. Early humans would have taken a dim view of peers who were slobs

Interestingly, women rarely become psychopaths – the disorder affects 10 males for every one female – and they have larger insulae than men, relative to total brain size. This anatomical distinction might explain why women are most sensitive to disgust, and might also have bearing on yet another traditionally feminine characteristic: women score higher than men on tests of empathy – a useful trait for gauging when a cranky baby has a fever or needs a nap.

Why moral and visceral disgust became entangled in our brains in the first place is harder to explain, but the ‘disgustologist’ Valerie Curtis of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine puts forward a scenario that, while impossible to verify, certainly sounds plausible. Evidence from prehistoric campsites suggests that our ancient ancestors might have been more concerned about hygiene and sanitation than commonly assumed. Some of the earliest artefacts from these sites include combs and middens (dumpsites for animal bones, shells, plant remnants, human excrement and other waste that might attract vermin or predators). Early humans, she strongly suspects, would have taken a dim view of peers who were slobs about disposing of their garbage, who spat or defecated wherever they pleased, or made no effort to comb the lice out of their hair. These inconsiderate acts, which exposed the group to bad odours, bodily waste and infection, triggered revulsion and so, by association, the offenders themselves became disgusting. To bring their behaviour into line, Curtis thinks, they were shamed and ostracised; and, if that failed, they were shunned – which is exactly how we react to contaminants. We want nothing to do with them.

Since similar responses were required to counter both types of threat, the neural circuitry that evolved to limit exposure to parasites could easily be adapted to serve the broader function of avoiding people whose behaviour endangered health. Complementing this view, Curtis’s team found that people who are the most repulsed by unhygienic behaviour are the most likely to endorse throwing criminals into jail and imposing stiff penalties on those who break society’s rules.

From this point in human social development, it took a bit more rejiggering of the same circuitry to bring our species to a momentous place: we became disgusted by people who behaved immorally. This development, Curtis argues, is central to understanding how we became an extraordinarily social and cooperative species, capable of putting our minds together to solve problems, create new inventions, exploit natural resources with unprecedented efficiency and, ultimately, lay the foundations for civilisation.

‘Look around you,’ she said. ‘There’s not one single thing in your life that you could have made on your own. The massive division of labour [in modern societies] has incredibly increased productivity. The energy throughput of humans nowadays is a hundred times what it was in hunter-gatherer times.’ The big question is: ‘How have we done this clever trick? How are we able to work together?’

Explaining why we might be induced to cooperate is not an easy task. Indeed, it has stymied many an evolutionary theorist. The gist of the problem is this: by nature, we are not altruists. When you bring people into a lab and have them play games with different rules to earn money, there are always the greedy who don’t mind if other people go away empty-handed. There are always those who will cheat if they think that they can get away with it. From endless iterations of these experiments, this much is clear: people cooperate only if it is more expensive for them not to cooperate.

Today, we have laws and police officers to enforce the rules. But they are modern inventions, and they build on something far more fundamental, the glue that has always held society together. Indeed, society would not exist were it not for this cohesive force – namely, disgust.

‘If you’re greedy, if you cheat me or steal my things, I could beat you up,’ Curtis said. ‘But you might hit me back. And you might get your big, strong brothers who will beat me up as well. So it’s probably not a great thing to do. It would be much better if I say: “She’s disgusting, she’s behaving like a social parasite, she’s taking more than her fair share of the cake,” and shun you. So I’m using my mental equipment that I’ve got from disgust to punish you. I’m punishing you by exclusion, not by a violent act. It doesn’t cost me anything. It’s hard for you to get back at me. And I can also get my big brother and talk to him and say: “Do you know what she did? She is so disgusting.” And he’ll go: “Oh yeah, she’s disgusting,” and spread the word.’

Charles Darwin thought our species’ social values might be driven by an obsession with ‘the praise and blame of our fellow man’. Indeed, we care more about our reputations than whether we’re really in the right or not. The face of contempt, which, Darwin noted, is identical to that of disgust, is a powerful deterrent. In prehistoric times, being excluded from the group for antisocial behaviour would have been tantamount to a death sentence. It is very hard to survive in the wild by your skills, fortitude and wit alone. Natural selection would have favoured cooperators, people who played by the rules and reciprocated in kind.

The use of disgust to curb the behaviour of the selfish – including those whose poor hygiene threatened the group’s welfare – was essential for our ancestors’ technological advancement in another way as well. While being sociable offers extraordinary benefits – we can trade goods, exchange labour, forge new alliances, and combine ideas – it also comes at a steep price. We are walking bags of germs. Working in proximity to others exposes everyone to infection. To gain the benefits of cooperation without this huge risk, we must ‘do this dance’, said Curtis: we must get close enough to collaborate but not so close as to jeopardise our health. We humans needed rules for achieving this delicate balancing act, and so we acquired manners.

‘From a very early age, we learn to be continent with our bodily fluids, not making nasty smells, not eating with an open mouth or spitting. It’s highly adaptive because that means you can sustain a social life at a lower [health] cost. People who break these rules are very rapidly socially excluded,’ Curtis said.

To her, manners are what separated us from animals and allowed us to take ‘the first baby steps’ en route to becoming civilised super-cooperators. Indeed, she thinks manners might have paved the way for ‘the great leap forward’, an explosion of creativity 50,000 years ago manifested by specialised hunting tools, jewellery, cave paintings and other innovations – the first signs that humans were sharing knowledge and skills, and working together productively.

Manners set our species on the track toward progress; but, to become truly civilised, humans needed a more elaborate code of conduct, one that would bind communities together: they needed religion. Fortunately for humanity, it emerged just when it was most needed – when our ancestors decided to put down literal roots.

About 10,000 years ago, some hunter-gatherers began experimenting with a radical new lifestyle: farming. Only a few of them did so at first, but the movement picked up steam; gradually, more people began to settle down, trading the wandering life for a patch of land, typically by a river delta.

Infectious diseases spread with alarming efficiency when there are a large number of hosts living near one another, especially under unsanitary circumstances. The advance of agriculture created those very conditions.

We are the heirs of exceptionally hardy people who were unusual in having immune systems that could repel these virulent germs

The first farmers could barely eke out an existence, being one crop failure away from disaster. Their grain-heavy diet was deficient in many nutrients and overabundant in others (the bacteria that cause cavities thrived on all those carbohydrates, triggering dental woes unknown to hunter-gatherers). Hunger and malnourishment combined to weaken their immune systems, making them more vulnerable to infection.

Ironically, as they became more successful at farming, their health problems only worsened. Their grain stores attracted insects and vermin that spread disease. With human settlement came piles of human waste and a greater danger that the water people drank was polluted with faecal contaminants. And the chickens, pigs and other animals that they domesticated brought them in contact with new pathogens for which they had no natural resistance.

As these risks mounted, early farmers fell prey to wave upon wave of diseases, including mumps, influenza, smallpox, whooping cough, measles and dysentery.

This didn’t happen overnight. It took thousands of years for agriculture to take off. Few cities in the Middle East, where the movement began, had more than 50,000 inhabitants prior to biblical times. So the perfect storm was slow to gather but, when it hit, a health crisis of unimaginable disruption and trauma ensued. These new diseases were far more lethal and terrifying than the versions manifested in the untreated and unvaccinated today. We are the heirs of exceptionally hardy people who were unusual in having immune systems that could repel these virulent germs. Those at the forefront of these epidemics likely fared far worse on average than our more recent ancestors. Consider the fate that awaited some of the first people to get syphilis: pustules popped up on their skin from their heads to their knees, then their flesh began to fall off their bodies, and within three months they were dead. Those lucky enough to survive the ravages of never-before-encountered germs rarely came away unscathed. Many were crippled, paralysed, disfigured, blinded or otherwise maimed.

It was exactly at this critical juncture that our forefathers went from being not particularly spiritual to embracing religion – and not just passing fads, but some of the most widely followed faiths in the world today, whose gods promised to reward the good and punish the evil. One of the oldest of these belief systems is Judaism, whose most hallowed prophet, Moses, is equally revered in Christianity and in Islam (in the Quran, he goes by the name Musa and is referred to more times than Muhammad). Half the world’s population follows religions derived from Mosaic Law – that is, God’s commandments as communicated to Moses.

Not surprisingly, given its vintage, Mosaic Law is obsessed with matters related to cleanliness and lifestyle factors that we now know play a key role in the spread of disease. Just as villages in the Fertile Crescent were giving rise to filthy, crowded cities, and outbreaks of illness were becoming an everyday horror, Mosaic Law decreed that Jewish priests should wash their hands – to this day, one of the most effective public-health measures known to science.

The Torah contains much more medical wisdom – not merely its famous admonishments to avoid eating pork (a source of trichinosis, a parasitic disease caused by a roundworm) and shellfish (filter feeders that concentrate contaminants), and to circumcise sons (bacteria can collect under the foreskin flap). Jews were instructed to bathe on the Sabbath (every Saturday); cover their wells (which kept out vermin and insects); engage in cleansing rituals if exposed to bodily fluids; quarantine people with leprosy and other skin diseases and, if infection persisted, burn that person’s clothes; bury the dead quickly before corpses decomposed; submerge dishes and eating utensils in boiling water after use; never consume the flesh of an animal that had died of natural causes (as it might have been felled by illness) or eat meat more than two days old (likely on the verge of turning rancid).

When it came time for divvying up the spoils of war, Jewish doctrine required any metal booty that could withstand intense heat – objects made of gold, silver, bronze or tin – to ‘be put through fire’ (sterilised by high temperatures). What could not endure fire was to be washed with ‘purifying water’: a mixture of water, ash and animal fat: an early soap recipe.

Equally prescient from the standpoint of modern disease control, Mosaic Law has numerous injunctions specifically related to sex. Parents were admonished not to allow their daughters to become prostitutes, and premarital sex, adultery, male homosexuality and bestiality were all discouraged, if not banned outright.

the use of disgust to punish people whose practices endangered the group could be leveraged to drum up moral outrage to condemn the cruel, the greedy and the malevolent

Religion is an ideal enforcer of good public health, for many of the behaviours most relevant to disease-propagation occur behind closed doors. There’s simply no way of getting around an omnipresent God ever on the lookout for those who defy His will. Lest His flock be tempted to stray from the fold, the Torah makes clear that there will be a steep health cost: the Lord will punish the disobedient with ‘severe burning fever’, ‘the boils of Egypt’, ‘with the scab, and with the itch’, ‘with madness and blindness’ – and, if all that fails, the sword.

The axiom ‘Cleanliness is next to godliness’ originated in Mosaic Law, and was subsequently embraced by Christianity and Islam. Hinduism evolved more independently, but is equally obsessed with bathing before prayer and concerned about contamination of the body and what parts should be allowed to touch other objects or people (the left hand, for example, is used strictly for bathroom functions, so it is a grave offence for a Hindu to offer food to someone with that hand).

Of course, the world’s great religions are about much more than hygiene. Indeed, they tend to be most preoccupied by matters related to spiritual purity, sacred duty and the preservation of the soul. But the use of disgust to punish people whose health practices endangered the group could easily be leveraged for the purpose of drumming up moral outrage to condemn the cruel, the greedy and the malevolent. This repurposing of the emotion gave society two benefits for the price of one as antisocial behaviour, like hygiene infractions, would be hard to police without the deterrent of an all-knowing God with a vengeful streak.

We might owe disgust a great debt for our manners, morals and religion – and ultimately our laws, politics and government, as the latter three can be built only on the former. Evolution got the ball rolling by making our ancestors revolted by parasites and any behaviour that exposed them to infection; then culture took over and transformed people into super-cooperators willing to abide by shared codes of conduct. At least, that’s one version of how, over the aeons, scattered tribes of nomads united to become global citizens whose minds are now wired together by the internet.

This perspective on human history is compelling in broad strokes, save for one caveat: it might shortchange biology’s role in our species’ recent moral development. Contrary to common assumption, human brains didn’t stop changing once people submitted to divine authority and became civilised. They kept on changing – especially, perhaps, in the very regions involved in processing disgust.

Admittedly, that’s conjecture. But discoveries from the forefront of genetics support my thinking. One of the most surprising findings to emerge from human gene-sequencing data in the past decade is that human evolution has been speeding up in recent times. In fact, adaptive mutations in our species’ genome have accumulated a hundred times more quickly since farming got underway than at any other period in human history and, the closer we move to the present, the quicker the adaptive mutations pile up.

Scientists were initially puzzled by this unexpected finding until it dawned on them that the catalyst behind this change was ourselves. Humans were radically transforming their environment by taking up the plow, and their bodies and behaviour had to adjust to the rapidly shifting landscape. In an evolutionary eyeblink, they had to adapt to new diets and very different lifestyles. Our species’ cooperative spirit – our ingenuity and ability to work together – forced us into evolution’s fast lane.

The quickest-changing sections of the human genome regulate the functioning of the immune system and the brain. Given disgust’s role in coordinating our physical and behavioural defences against infection, it stands to reason that the parts of the brain that the emotion engages could have undergone significant remodelling with the rise of civilisation.

That argument is even more convincing when you consider that large segments of populations were decimated by plague and pestilence over that very period. Natural selection would have strongly favoured people who believed in God or who, at the very least, were conscientious in obeying religious doctrine that served to protect their health. Most important, it would have favoured the survival of people with a punitive streak – that is, those prone to stiffly penalise anyone who broke society’s rules. And as agriculture gave way to industry, causing a massive migration from farms to factories, and concentrating more people than ever before into sprawling, squalid slums, these pressures surely would have only intensified.

While there is uncertainty as to when and how disgust became embedded in our system of ethics, there can be no doubt that its influence on society has been transformative. Without this powerful emotion to keep us all in line, we could not have achieved so much as a species. Miraculously, disgust has got us to cooperate without raising a fist – indeed, often without so much as a slap on the wrist. It has elicited so much good merely by the shaming and shunning of those whose actions harm the group.

For that reason, some thinkers have come to view disgust as a sacred gift. Leon Kass, chairman of the President’s Council on Bioethics under the administration of George W Bush, counselled that we should heed ‘the wisdom of repugnance’. This voice that wells up inside us warns when a moral boundary has been crossed, he argued. In an article for the New Republic in 2001, he called for people to listen to its outrage at acts such as human cloning, abortion, incest and bestiality. Repugnance, he wrote, ‘speaks up to defend the central core of our humanity. Shallow are the souls who have forgotten how to shudder.’

Needless to say, Pizarro has a less rosy view of disgust – and not without cause. As we’ve seen, it can make prejudice feel right, justifying the stigmatisation of immigrants, homosexuals, the homeless, the obese and other vulnerable groups. Moreover, our natural revulsion to disease has fed into the notion that sickness is God’s punishment for sin – a view that still persists around the world even as modern medicine has dramatically advanced.

Our brains are also prone to viewing primary disgust elicitors such as blood and semen as agents of evil. In many cultures, a woman who has been raped is treated like a sinner. She is tarnished, no longer virtuous or to be valued. No man will be with her because she has been corrupted by another man’s crime. The fact that women menstruate has further stoked the flames of misogyny, for this ‘bad blood’ is often seen as God’s curse, proof of their inferior moral status. In many cultures, menstruating women are confined to separate quarters so as not to contaminate others. Orthodox Jews are prohibited from sitting on a chair that a menstruating woman has occupied. Hindus must bathe and change their clothes if they come in contact with women in this ‘impure’ state. Even in more secular pockets of the world, many men and women believe it is wrong to have sex when a woman has her period. Owing to how disgust affects our thinking, it’s all too easy for women to be viewed as both polluting and morally offensive, and thus deserving of fewer rights than men.

a study of mock jurors found that those prone to disgust were more inclined to judge ambiguous evidence as proof of criminal wrongdoing, impose stiffer sentences, and see the suspect as wicked

From a legal standpoint, disgust is also problematic – and not just because of the racist implications of having minds that equate dark skin with contamination and sin. Disgust leads us to view gory crimes as the most egregious of offences and therefore worthy of the severest punishment. Consequently, the murderer who cuts a person’s throat is likely to get a stiffer sentence than the one who kills more tastefully – say, by adding a dash of arsenic to the victim’s tea or pressing a pillow over his face. Admittedly, a dead body is still not pretty, but an intact corpse tends to go over better with juries than one smeared with blood and chopped into pieces.

Pizarro is disturbed by the logic of putting someone away longer for a crime that is grisly versus one that’s cleanly executed. ‘It’s a tricky question. Do you show the gory pictures of the murder during sentencing?’ As he points out, those images have nothing to do with whether or not the defendant committed the crime. ‘The judge can’t just say: “Don’t let this emotion influence you.” It would be great if that’s how human beings work, but you can’t undo that.’

Even more troublesome, a study of people serving as mock jurors found that those highly prone to disgust were more inclined to judge ambiguous evidence as proof of criminal wrongdoing, to impose stiffer sentences, and to see the suspect as wicked. Compared with their less easily revolted counterparts, they were also more prone to harbouring an exaggerated sense of the prevalence of crime in their own neighbourhoods. A related study whose participants included law students, police cadets and forensic experts similarly showed that disgust sensitivity correlated with a tendency to judge crime more severely and punish the perpetrators with longer sentences – and this association held up even for veteran forensic experts who were accustomed to seeing gruesome evidence. To put it plainly, prosecutors benefit from having jurors with acute sensitivity to disgust, while defence attorneys (and the defendants) gain from having jurors with the reverse disposition.

‘I’ve been approached by people who do work for jury selection,’ said Pizarro, ‘and they wanted to know what to tell lawyers about this. It creeped me out because you really could use this emotion to your advantage, and I don’t want to be a part of that.’

If disgust makes us less tolerant of people who break the law, then perhaps we should welcome it into our lives? Pizarro is not persuaded by that line of logic. ‘I do a podcast with a philosopher friend of mine and his take on this is: “To the extent that disgust can fuel your belief that, say, molesting children is wrong, then bring on disgust.” My response is: “I hope that you’d be opposed to child molestation on plenty of other grounds that don’t require being grossed out at the thought of it.” ’ Still, he conceded: ‘Maybe this is harder to do in real life.’

While people might not be able to suppress their moral intuitions, Pizarro would like them to challenge these sentiments with reason and logic. It might take long and arduous intellectual work to reach an ethical decision – for example, that slavery should be abolished or it’s cruel to eat animals – but with the passage of time, he said, our new values can become automatic and intuitive.

If more people favoured reason over emotion in making moral decisions, would politics be less polarised?

‘We think of ethical views as wildly different across individuals and across cultures, but the truth is that there’s a ton of agreement,’ said Pizarro. ‘Most people think that murder, rape, stealing, lying and cheating are wrong. What’s interesting is where they diverge. Those differences have become a hotbed of political rhetoric and abuse.’ And as he notes, where people clash predominantly relates to sexual mores and other social values highly pertinent to the transmission of disease. Which potentially implies something radical: it’s parasites that have divided us. So if we could eradicate the worst of them and tamp down our disgust, perhaps people’s attitudes would change and political debates would not be so rancorous.

Of course, that’s absurdly simplistic. Abortion could become more heinous if you’re easily disgusted, but fundamentally this lightning-rod issue is about whether or not you think it’s murder. Opposition to gay rights might stem from the belief that children will be better off in a traditional family, one headed by husband and wife, rather than revulsion at the thought of anal sex. Hostility toward immigrants is largely based on concerns that they’re taking jobs away from a nation’s citizens or might pose a security threat – not fears that they’re going to make people sick. Not everything is about parasites.

With that caveat in mind, entertain an even wilder idea: maybe we’ve underestimated parasites’ political clout. Maybe they permeate our entire worldview. Maybe geopolitics should be taught from a parasite’s point of view.

This is an excerpt of the chapter, ’Parasites and Piety’, from THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON PARASITES: How Tiny Creatures Manipulate Our Behavior and Shape Society by Kathleen McAuliffe, Copyright © 2016 by Kathleen McAuliffe. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.