Love, in the world of Walt Disney films, has changed. Between Tangled (2010) and Moana (2016), the ideal of heterosexual romance has been dethroned by a new ideal: family love. The happy ending of our most-watched childhood stories is no longer a kiss. Today, Disney films end with two siblings reconciled despite their differences, as in Frozen (2013); or a mother and a daughter making amends, as in Brave (2012) and Inside Out (2015); or a child reunited with long-lost parents, as in Tangled, Finding Dory (2016) and Coco (2011). Love remains the all-important linchpin of these stories: love is supposed to bring us joy, solve our problems, and get us to our happy ending. We are told to love love, for love will always save us in the end. But over the past 10 years, we have been told to love a new kind of love.

The stories of love we find on the silver screen are not just representations of the emotions within us. They also shape our expectations of what love will be like – expectations by which we will want to abide, leading us to shoehorn our feelings into that idealised form. Just a few centuries ago, romance held a much less central position in the cultural imaginary than it does today: love was primarily a question of family allegiances and controlled reproduction. This changed with the advent of modernity, where romantic love acquired the cultural acclaim that it commands today. And if the nature of love has changed before, it can change again. Disney’s depiction of love over the past decade might be a sign of what’s to come. Love is central to the fabric of society, so any change in its ideal will ripple through all sorts of human relations: between workers and bosses, between states and their citizens, between the ideals of modernity and those who are branded as ‘ethnic others’, to name but a few.

Today, Disney no longer expects us to expect a knight in shining armour, but rather to forgive our siblings and make peace with our parents. Consider the gulf that separates Sleeping Beauty (1959) from its remake Maleficent (2014). Both are based on Charles Perrault’s La Belle au bois dormant (1829), but in Maleficent the story has been updated for the times. The princess is still told that only a ‘true love’s kiss’ will end her magic sleep. The prince’s lips, however, have now lost their power. We see him kiss the princess and the music swells – and nothing happens. But when the fairy godmother then realises her mistake in cursing the princess and bends down to kiss her forehead in remorse, she wakes. The story arc is still the same as of old, but the words ‘true love’ now mean something new.

The tipping point was Tangled. There were intimations to be found already in Finding Nemo (2003), but it was Tangled that first showed us how dramatic the shift away from romance would end up being. The plot pits the two forms of love against each other. One thread of the story is about Rapunzel’s ambiguous relation with her adoptive parent, Mother Gothel, while the other is about her romance with the swashbuckling bandit Flynn Rider. At first, it seems as if romance wins the day. Rapunzel and Rider abscond, and Gothel falls to her death, leaving Rapunzel free to find her way home to her biological parents. But in the end, the romantic relationship that is supposed to be the centre of the story falls curiously flat. Rider is just too perfect. His romance with Rapunzel is simple and light-hearted – sweet, but hardly the stuff of great passion. Rapunzel’s bond with Gothel, on the other hand, is far more complex and far more interesting. The relationship is by turns abusive and nurturing, exploitative and caring, terrifying and funny, and all the more entertaining for the way it takes well-worn clichés about overprotective mothers and their teenage daughters, and turns them into the psychotic manipulations of an evil witch. With Tangled, romance might have won the battle, but it lost the war. Even if Gothel had to die in the end, she showed just how much narrative gold could be mined from family love.

It’s not just the word ‘love’ that has changed meaning over the past 10 years of Disney. The word ‘family’ has done the same. Neither Mother Gothel nor the fairy godmother of Maleficent are the biological parents of the films’ main characters, but they still end up taking emotional centre-stage because the actual biological parents are either cruel and psychotic, as in Maleficent, or distant and idealised, as in Tangled. Parenthood is determined by one’s emotional bonds. As a result, the very question of what counts as a ‘family’ in Disney has become more ambiguous and more modern. In Finding Dory, an overjoyed Dory finally gets what she always wanted: a family. But that family is a rather patchwork affair, a mixture of biological, adoptive and indeterminate relations. The happily-ever-after scene includes Dory and her parents, but also Marlin, Dory’s friend, surrogate brother and not-quite romantic partner, as well as Marlin’s son Nemo and a coterie of various friends and their relatives. Dory hasn’t only found a nuclear family. She has crafted an extended family out of bits and pieces of emotional attachment.

It is not that older Disney films lacked adoptive families – on the contrary, the majority of the classics are populated by orphans and stepmothers. But crucially, films such as Cinderella (1950) hardwired our collective conception of step-parents as Bad News. For the main characters, living with a parent to whom they are not biologically related seems just a step short of a prison sentence. Biological parenthood was the golden ideal against which our orphaned heroine’s fate could be held up as an unbearable misery. By contrast, in Maleficent and Finding Dory, living with adoptive parents or self-crafted families is not a misfortune for our heroines to overcome, but a happy ending for them to achieve. The shift towards family love has also made ‘family’ a far more capacious concept. That is both the main advantage of this new development and, as it turns out, its most insidious threat.

A frenzied orgy of Lego bricks whirls across the screen, flashing the words: FRIENDS. ARE. FAMILY

It was only when watching The Lego Batman Movie (2017) that I realised the political implications of all this. The hero of the original Lego Movie (2014) was a seemingly unremarkable construction worker called Emmet, and its villain a billionaire CEO named Lord Business bent on world domination, a brilliant Lego-size embodiment of ruthless capitalism. For a moment, this seemed like the kind of narrative I could get behind, with class struggle reconfigured as a plastic-toy action movie, to the tune of a theme song that got stuck on our collective head for months: ‘Everything is AWESOME! Everything is cool when you’re part of a team!’ There’s a romantic side plot in the film, but it’s just a side plot. The movie’s most important affective community isn’t the romantic couple but something much more like a labour union: workers teaming up to combat the interests of their capitalist employers. But even then, the new ideal of love was creeping in. Towards the end, it’s revealed that the entire plot has been the fantasy of a child playing with his Lego bricks, and that Lord Business is actually a playtime projection of his insensitive father. And just like that, the intimations of a Disneyfied critique of capitalism collapsed into family drama. Power relations were mapped onto family relations, and lost all bite.

While the villain of The Lego Movie is a billionaire CEO, in The Lego Batman Movie a billionaire CEO is the hero. Forget workers teaming up. The drama in the new film is all about friendship and father figures and Batman’s attachment issues. Of course, it all works out in the end, as Batman learns the value of community and patches together his own version of a family, with Alfred as a surrogate father and Robin as an adopted son. In the closing credits, a frenzied orgy of Lego bricks whirls across the screen, and in the eye of this neon storm flash the words: FRIENDS. ARE. FAMILY. The lyrics repeat the new dogma of love what feels like a thousand times, so as to really drive the message home: your affections belong to the family now, whatever their form. Meanwhile, Alfred, Batman and Robin scuttle across the screen holding signs that identify them as Older Father, Father and Son, respectively. Of course, none of them are biologically related, but that doesn’t matter, because – remember – FRIENDS. ARE. FAMILY.

As in Finding Dory, families are what we make of them. Alfred and Batman might not actually be father and son, but that doesn’t matter if all forms of positive attachment can be construed as familial. What they are, however, is employer and employee. Alfred is Batman’s butler, but that hierarchy is entirely obscured by the ideal of family love. No more being ‘part of a team’, no more anti-capitalist Lego bricks, now it’s all one big happy family, where exploitation of labour can be cast as the love that is owed by one family member to another. The concept of the family that has taken centre-stage in Disney might be more capacious than its predecessor, it might allow for much-needed alternatives to the old ideal of biological nuclear families as the only ‘true’ kind of family. But the new concept is also so very capacious that it can end up enfolding and eventually concealing other forms of social relations, including relations of labour and differences in power.

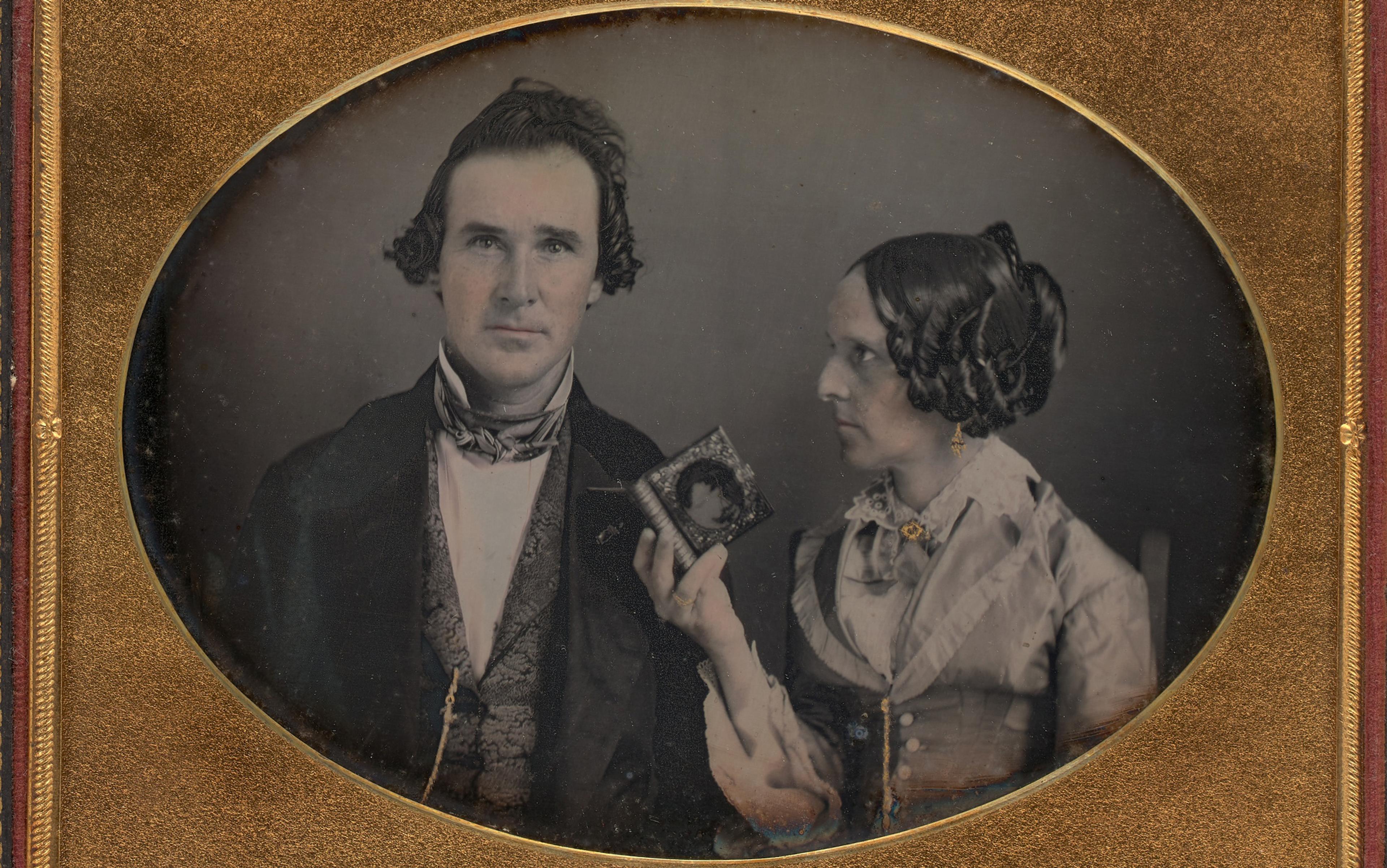

Why should all of this matter? Why should we care what children’s films have to say about love? Disney has an answer, and it’s a good one. In Frozen, princess Anna is overjoyed at the prospect of her sister’s coronation. After having been confined to her castle for a decade, she finally has a chance to meet new people, and so she walks through the castle’s art galleries fantasising about romance. She jumps up in front of a series of paintings that display the kind of love she yearns for, arranging her own body to match the women they portray, twisting herself into art. Unsurprisingly, in the next scene she falls in love with the first stranger she meets.

Anna’s bodily mimicry tells you all you need to know about the cultural politics of emotion. Our emotional expectations are shaped by the cultural products that surround us, like the paintings in Anna’s castle. They arrange our bodies and mould our attachments. Love is pure fantasy, thoroughly shaped by cultural representation and then repeated in our own behaviour. Indeed, Anna’s monologue in this scene is a miniature lesson in the paradox of Western romance. She fantasises about the encounter with the dashing stranger whom she expects to meet at the gala, rehearsing it step by step in her mind: ‘Then we laugh and talk all evening, which is totally bizarre – nothing like the life I’ve led so far!’ This is romance in a nutshell. Bizarre, exceptional, unpredictable, unique every time – and also predictable from start to finish, a pattern that can always be rehearsed in advance, and that is fully shaped by the discourse of our culture. It’s basically Judith Butler’s theory of the heterosexual matrix delivered as fairy-tale musical montage. What’s not to love?

What is really striking about the sequence is that Anna’s preparations for the party are cross-cut with her sister’s. Elsa is about to be crowned queen, but fears that she will accidentally reveal her hidden magical powers during the ceremony. She rehearses it by standing in front of a painting of her father’s coronation, arranging her own body to match her father’s, just like Anna. But unlike Anna, Elsa seems to be clearly aware of the performative nature of what lies ahead, singing to herself: ‘Put on a show, make one wrong move and everyone will know.’ This, then, is the nature of power in Frozen, and it turns out to be a lot like love: it’s a show that has to be put on according to the dictates of cultural precedence. Love and power are flip sides of the same coin, because they are both ways in which bodies are arranged into shape by the cultural products that surround us. Like paintings. Or Disney films.

It’s strange to get a lesson in the politics of emotion from Frozen, of all places, but here we are. (Teacher’s tip: Frozen is a great way to tell your students about Michel Foucault.) But the film’s analysis of romance and royalty is made possible only by the fact that we don’t really believe in those things anymore, in this post-feudal, post-romantic, family-loving age. Having exposed romantic love as a kind of cultural mimicry rather than as an innate emotion, Frozen then goes on to extol the love that links the two sisters as magical and natural. Anna is told that the curse that afflicts her can be lifted only by an act of true love, but she is unsure: is her true love the stranger she met at the party, Hans, or another man she met later, Kristoff? In the end, it turns out to be Elsa. As in Maleficent, the true love that lifts curses is the love between family members: romance might be something we learn, but families are the stuff of magic. Just as Anna and Elsa copy and repeat the scenes of their paintings, so will millions of children copy and repeat whatever emotional ideal they find glorified in Disney. Family bliss is no less rehearsable than romance.

The family, as a space of fantasy, is better than romance at accommodating ambivalence

Only 10 years ago, the hegemony of Disney romance seemed unshakable. Looking through the list of classics – Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), Cinderella (1950), The Little Mermaid (1989), Beauty and the Beast (1991), Aladdin (1992) – one got the feeling that we were in for a neverending barrage of shining armour and white wedding gowns, climactic kisses and happily-ever-after heterosexuality. As much as The Lego Batman Movie fills me with apprehension about the new ideal, at least it’s a change. So what did change?

I think the answer lies in the relation between love and complexity. Lauren Berlant, professor of English at the University of Chicago, argues in Desire/Love (2012) that our idea of ‘love’ denotes a kind of self-defeating desire for simplicity. When we love someone, we want to love only them and feel nothing but love for them. But our muddled desire keeps frustrating the simplicity of our attachments, throwing us back into emotional ambiguity. Love, then, is our attempt to murder that ambiguity over and over again, and regain simplicity: I love only you, and all I feel for you is love.

For Berlant, that is why love relies so heavily on fantasy. Fantasy gives us a space of imaginative freedom, where we can organise our tricky emotions however we want. We can arrange complexity to make it look simple. Love stories typically involve the same narrative sequence: an initial love interest is followed by a series of setbacks and complications, which are then overcome to yield a happy ending where all is well and good. In this space of pure fantasy, all the pain, ambivalence and complications that come from love can be placed in the middle of the story, bracketed by an exciting beginning and a happy ending that supposedly reveal the true nature of love. The ambiguity is just the stuff in the middle. In the end, love will always show its true and simple colours. Love stories tell us to hang in there: romance is fundamentally a good thing, if only you wait long enough. Anytime now.

Maybe we got tired of waiting. Maybe romantic love could no longer sustain the faith that we need in order to endure the ambivalence of everyday attachments. Family love seems to be a much better container for complexity. With the ideal of the family comes a sense of natural obligation to one’s siblings and parents, an obligation that can survive whatever spats and mixed feelings life throws our way. We are perfectly used to the idea of siblings fighting or teenagers yelling at their parents while being also, deep down, extremely fond of each other. We naturally see these expressions of annoyance as surface ripples on a sea of love.

Of course, this sense of ‘deep down’ is an illusion. The idea that family members will always love one another is no more natural than the idea that romantic love will always save us in the end. But the family, as a space of fantasy, is better than romance at accommodating ambivalence. Complexity fits far better into its frame, so we can more easily believe that the pain that comes with family love will eventually be followed by a happy ending. Anytime now.

In Frozen, Kristoff brings Anna to his adoptive family, a tribe of stone trolls living in the forest. Anna believes that it’s Hans whom she truly loves, not Kristoff, but the trolls insist otherwise. They stage an elaborate ceremony where they literally tie the knot between Kristoff and Anna, binding them in full-body bondage while singing in unison that romantic love can ‘fix [you] up’ and solve your problems. The trolls, it seems, haven’t got the memo. Like Friedrich Nietzsche’s hermit, they haven’t heard in their forest that Romance is dead.

The scene is a neat solution to a practical problem that comes with the new ideal of love. Frozen was stuck right in the middle of the transition between romance and family bliss. In Moana, for example, there is no romantic love to speak of, the old ideal has been completely usurped by the new. But in the earlier films, the two ideals exist side by side. In Tangled, romantic love still holds the upper hand, while in Frozen the roles have been flipped – here, it’s family love that ultimately wins the day. But both films still contain a tension between two forms of love that cannot both be ‘the one true love’.

In Frozen, the solution is to ship the old ideal elsewhere, outside the borders of civilised culture and over to the trolls, who become the unlikely spokespeople for an outdated faith in marriage. The directors of Frozen attracted a measure of controversy by suggesting that the trolls were inspired by the Sami people, an ethnic group living in northern Scandinavia. The trolls are mainly shown in a positive if somewhat stereotypical light – as noble savages magically in touch with nature – and, of course, there is nothing intrinsically wrong about being made to advocate marriage. But it is telling that it is this ‘ethnic other’ who must bear the brunt of obsolete ideals. In celebrating a romantic kind of love that the film has earlier exposed as somehow ‘fake’, the trolls easily fit into the stereotype of non-white ethnicities as naturally backwards: less modern, less woke to the nature of love in our time.

In the end, the question of what we see as true love is related to the question of who can be part of that ‘we’. As Frozen’s cross-clipping between Elsa’s and Anna’s monologues reminds us, love and the state are flip sides of the same coin. Those who live in the same nation are expected to love that nation. In fact, according to the feminist writer and scholar Sara Ahmed in The Cultural Politics of Emotion (2004), nations are a product of such love: the nation comes about because, through a shared investment in its ideal, we turn our bodies in certain ways, abide by a certain set of rules, thereby creating boundaries and communities, cultures and customs. The love for the nation creates the nation; the things we are expected to like about the nation determine what the nation will be like. Or, to put it another way, without a shared emotional investment in the community, there is no community at all.

As a result, when the ideal of love changes, so does the relation between the state and its borders. It is not only that everyone in a community is expected to love that community, everyone is also expected to share a basic understanding of what it means to love – and if you don’t, you can go live with the trolls. In Frozen, love draws the boundary between the nation that Elsa rules and the backward denizens of the forest outside it. Love separates those who are in the know from those who are left in the cold.

I am thoroughly indebted to Mons Bissenbakker, without whom this essay would never have been written.