In 1996 I left Russia for the first time to spend a school year in the United States. It was a prestigious scholarship; I was 16 and my parents were very excited about the possibility of my somehow slipping into Yale or Harvard afterwards. I, however, could think of only one thing: getting an American boyfriend.

In my desk, I kept a precious document of American life, sent to me by a friend who had moved to New York a year earlier: an article about the Pill, ripped from the US girls’ magazine Seventeen. I read it lying in bed, feeling my throat getting dry. Staring into its glossy pages, I dreamed that there, in a different country, I would turn into someone beautiful, someone boys turned their heads for. I dreamed that I would need this kind of pill, too.

Two months later, on my first day at Walnut Hills High School in Cincinnati, Ohio, I went to the library and borrowed a stack of Seventeens that stood taller than me. I was determined to find out precisely what happened between American boys and girls when they started liking each other, and what I was supposed to say and do in order to reach the stage when ‘the Pill’ would prove necessary. Armed with a highlighter and a pen, I looked for words and expressions that had to do with American conduct in courtship and wrote them out on separate cards, just like my English teacher in St Petersburg had taught me.

I soon gathered that the lifecycle of a Seventeen-approved relationship went through several clear stages. First, you developed a ‘crush’, normally on a boy a year or two older than yourself. Then, you asked around a bit to establish whether he was a ‘cutie’ or a ‘moron’. If he was the former, Seventeen gave you thumbs up to ‘hook up’ with him once or twice after ‘asking him out’. Throughout the process, several boxes needed to be ticked: did you feel like the young man ‘respected your needs’? Were you comfortable ‘asserting your rights’ – in particular, refusing or initiating ‘body contact’? How was the ‘communication’? If any of the boxes remained unticked, you would ‘dump’ him and start looking for a replacement, until someone who was ‘good boyfriend material’ came along. Then you would start ‘making out on the couch’ and graduate into a Pill‑user.

Sitting in the American school library, I stared at my dozens of handwritten notes and saw an abyss opening up: a gulf between the ideals of love that I had grown up with and the exotic stuff I was now encountering. Where I came from, boys and girls were ‘falling in love’ and ‘seeing each other’; the rest was a mystery. The teen film drama that my generation of Russians grew up with – a socialist replica of Romeo and Juliet set in a Moscow commuter neighbourhood – was deliciously unspecific when it came to declarations of love. To express his feelings for the heroine, the protagonist recited the multiplication tables: ‘Two times two is four. It is as certain as my love. Three times three is nine. That means you are mine. And two times nine is 18, and that’s my favourite number because at 18 we will get married.’

What else was there to say? Not even our 1,000-page Russian novels could match the complexity of Seventeen’s romantic system. When engaging in love affairs, the countesses and officers were not exactly eloquent; they acted before they spoke, and afterwards, if they weren’t dead as a result of their hasty undertakings, they gazed around speechless and scratched their heads in search of explanations.

Although I did not yet have a PhD in sociology, it turned out that what I had been doing with the copies of Seventeen was exactly the kind of work that sociologists of emotion perform in order to understand how we conceptualise love. By analysing the language of popular magazines, TV shows and self-help books and by conducting interviews with men and women in different countries, scholars including Eva Illouz, Laura Kipnis and Frank Furedi have demonstrated clearly that our ideas about love are dominated by powerful political, economic and social forces. Together, these forces lead to the establishment of what we can call romantic regimes: systems of emotional conduct that affect how we speak about how we feel, determine ‘normal’ behaviours, and establish who is eligible for love – and who is not.

The clash of romantic regimes was precisely what I was experiencing on that day in the school library. The Seventeen girl was trained for making decisions about whom to get intimate with. She rationalised her emotions in terms of ‘needs’ and ‘rights’, and rejected commitments that did not seem compatible with them. She was raised in the Regime of Choice. By contrast, classic Russian literature (which, when I was coming of age, remained the main source of romantic norms in my country), described succumbing to love as if it were a supernatural power, even when it was detrimental to comfort, sanity or life itself. In other words, I grew up in the Regime of Fate.

These two regimes are based on opposing principles. Both of them turn love into an ordeal in their own ways. Nevertheless, in most middle-class, Westernised cultures (including contemporary Russia), the Regime of Choice is asserting itself over all other forms of romance. The reasons for this appear to lie in the ethical principles of neo-liberal, democratic societies, which regard freedom as the ultimate good. However, there is strong evidence that we need to re-consider our convictions, in order to see how they might, in fact, be hurting us in invisible ways.

To understand the triumph of choice in the romantic realm, we need to see it in the context of the Enlightenment’s broader appeal to the individual. In economics, the consumer has taken charge of the manufacturer. In faith, the believer has taken charge of the Church. And in romance, the object of love has gradually become less important than its subject. In the 14th century, gazing at Laura’s golden tresses, Petrarch had called the recipient of his affections ‘divine’ and believed her to be the most sublime proof of God‘s existence. Some 600 years later, another man bedazzled by a different heap of golden tresses – Thomas Mann’s Gustav von Aschenbach – concluded that it was he, not the handsome Tadzio, who was the touchstone of love:

[T]he lover was nearer the divine than the beloved; for the god was in the one but not in the other – perhaps the tenderest, most mocking thought that ever was thought, and source of all the guile and secret bliss the lover knows.

This observation from Mann’s novella Death in Venice (1912) encapsulates a great cultural leap that occurred somewhere close to the beginning of the 20th century. Somehow, the Lover pushed the Beloved from the centre of attention. The divine, unknowable and unreachable Other is no longer the subject of our love stories. Instead, we are interested in the Self, with all its childhood traumas, erotic dreams and idiosyncrasies. Examining and protecting this fragile Self by teaching it to pick its affections properly is the main project of the Regime of Choice – a project brought to fruition using a popularised version of psychotherapeutic knowledge.

The most important requirement for choice is not the availability of multiple options. It is the existence of a savvy, sovereign chooser who is well aware of his needs and who acts on the basis of self-interest. Unlike all previous lovers who ran amok and acted like lost children, the new romantic hero approaches his emotions in a methodical, rational way. He sees an analyst, reads self-help literature and participates in couples counselling. Moreover, he might learn ‘love languages’, read into neuro-linguistic programming, or quantify his feelings by marking them on a scale from 1 to 10. The American philosopher Philip Rieff called this type ‘the psychological man’. In Freud: The Mind of a Moralist (1959), Rieff describes him as ‘anti-heroic, shrewd, carefully counting his satisfactions and dissatisfactions, studying unprofitable commitments as the sins most to be avoided’. The psychological man is a romantic technocrat who believes that the application of the right tools at the right time can straighten out the tangled nature of our emotions.

This, of course, applies to both genders: the psychological woman also follows the rules, or, rather The Rules: Time-tested Secrets for Capturing the Heart of Mr Right (1995). Here are just some of the time-tested secrets assembled by its authors Ellen Fein and Sherrie Schneider:

Rule 2. Don’t Talk to a Man First (and Don’t Ask Him to Dance)

Rule 3. Don’t Stare at Men or Talk Too Much

Rule 4. Don’t Meet Him Halfway or Go Dutch on a Date

Rule 5. Don’t Call Him and Rarely Return His Calls

Rule 6. Always End Phone Calls First

The premise of The Rules is simple: because men are genetically wired to chase women, if women show them even the tiniest degree of empathy or interest, this has the effect of upsetting the biological equilibrium, ‘emasculating’ the man and reducing the woman to the status of a miserable abandoned she-animal.

That minefield of unreturned calls and ambiguous emails must be minimised. No more tears. No more sweaty palms. No more poetry, sonatas, paintings

The Rules has been criticised for an almost idiotic degree of biological determinism. Nevertheless, new editions continue to appear, and the ‘hard-to-get’ femininity that it advocates has become a commonplace of modern dating advice. Why does it remain so popular? The reason surely lies in its underlying message:

One of the greatest payoffs of doing The Rules is that you grow to love only those who love you. If you have been following the suggestions in this book, you have learned to take care of yourself. […] You are busy with interests and hobbies and dating, and you are not calling or chasing men. […] You love with your head, not just your heart.

In the Regime of Choice, the no-man’s land of love – that minefield of unreturned calls, ambiguous emails, erased dating profiles and awkward silences – must be minimised. No more pondering ‘what if’ and ‘why’. No more tears. No more sweaty palms. No more suicides. No more poetry, novels, sonatas, symphonies, paintings, letters, myths, sculptures. The psychological man or woman needs only one thing: steady progress towards a healthy relationship between two autonomous individuals who satisfy each other’s emotional needs – until a new choice sets them apart.

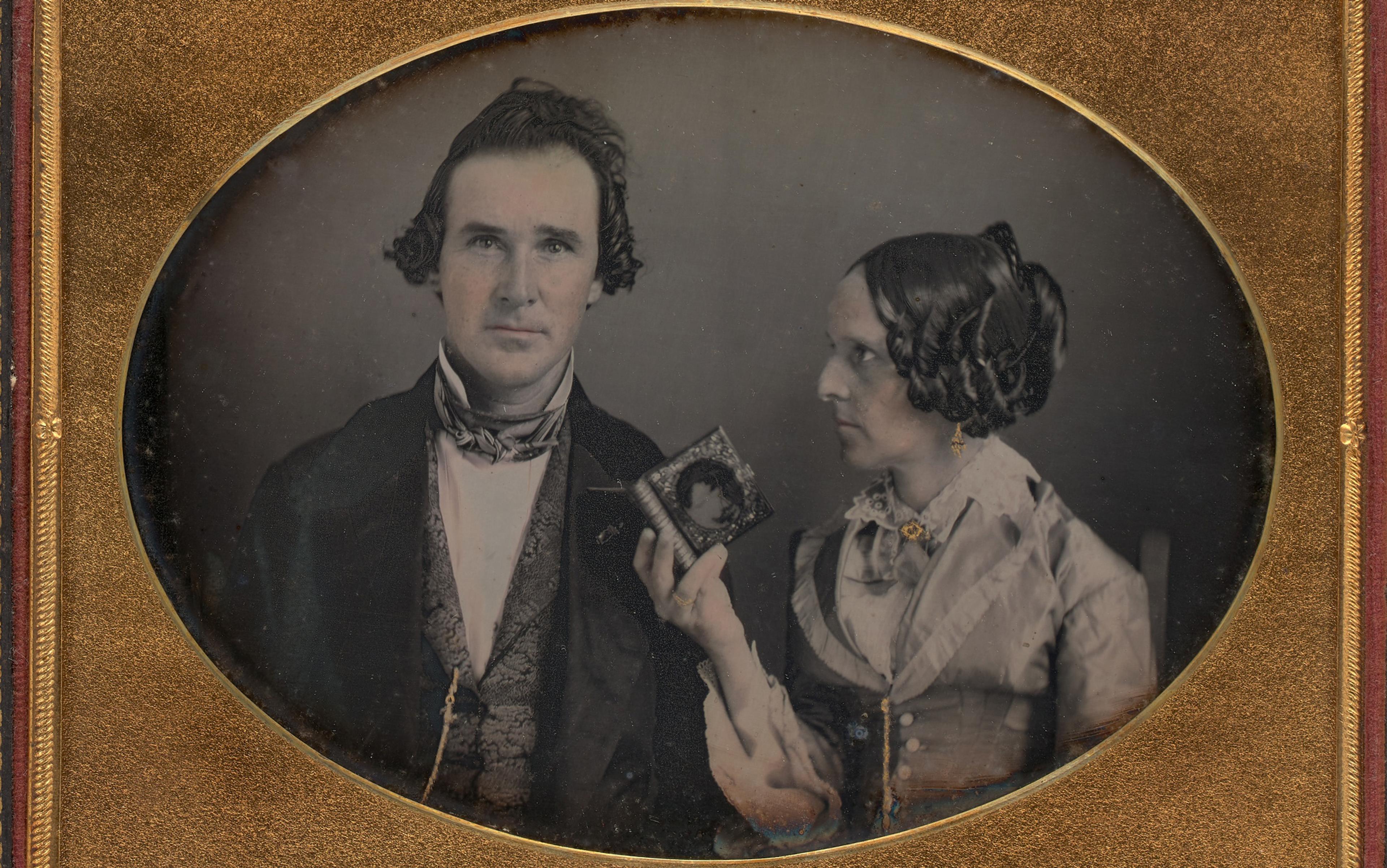

This triumph of choice is also bolstered by socio-biological arguments. Lifelong captivity in a bad relationship, we are told, is for Neanderthals. Helen Fisher, a professor of anthropology at Rutgers University and the world’s most famous love researcher, suggests that we have outgrown our millennia-long agricultural heritage, and no longer need monogamous relationships. We are now evolutionarily impelled to seek different partners for different needs – if not simultaneously, then at different stages of our lives. Fisher celebrates the modern lack of pressure to commit: we should all, ideally, spend at least 18 months with someone to decide whether they are good for us and whether we make a good match. With the absolute availability of contraceptives, unwanted pregnancies and disease can be fully eradicated; childbearing is fully disengaged from courtship, and so we can take the time to give our potential partner a test-drive without fear of the consequences.

Compared with other historical conventions about romance, the Regime of Choice might seem like a Gore-Tex jacket next to a hair shirt. Its greatest promise is that love needn’t cause pain. According to the polemics that Kipnis develops in Against Love (2003), the only suffering the Regime of Choice recognises is the supposedly productive strain of ‘working on a relationship’: tears shed in the couples therapist’s room, wretched attempts at conjugal sex, daily inspection of mutual needs, the disappointment of a break-up with someone who is ‘not good for you’. You are allowed to have sore muscles but you cannot have accidents. By making heartbroken lovers into the authors of their own trouble, popular advice produces a new form of social hierarchy: an emotional stratification based on the misidentification of maturity with self-sufficiency.

And this, argues Illouz, is precisely why 21st-century love still hurts. First, we lack the legitimacy of those love-torn duelists and suicides of the previous centuries. They at least enjoyed social recognition based on the general understanding of love as a mad, inexplicable force that not even the strongest minds can resist. Nowadays, yearning for a specific pair of eyes (or legs, for that matter) is no longer a valid occupation, and so one’s love pangs are exacerbated by the consciousness of one’s social and psychological inadequacy. From the perspective of the Regime of Choice, the heart-broken Emmas, Werthers and Annas of the 19th century are not simply inept lovers – they are psychologically illiterate, if not evolutionarily passé. Mark Manson, a relationship coach with more than 2 million readers online, writes:

Romantic sacrifice is idealised in our culture. Show me almost any romantic movie and I’ll show you a desperate and needy character who treats themselves like dog shit for the sake of being in love with someone.

In the Regime of Choice, committing oneself too strongly, too early, too eagerly is a sign of an infantile psyche. It shows a worrying readiness to abandon the self-interest so central to our culture.

Second, and even more importantly, the Regime of Choice is blind to structural limitations that make some people less willing – or less able – to choose than others. This occurs not only because we have unequal endowments of what the British sociologist Catherine Hakim calls ‘erotic capital’ (that is, some of us are prettier than others). In fact, the biggest problem about choice is that whole groups of individuals might, actually, be disadvantaged by it.

a bubble bath cannot substitute for a loving gaze or a long-awaited phone call, let alone make you pregnant – whatever Cosmo might suggest

Illouz, a professor of sociology at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, has argued persuasively that the individualistic appeal of the Regime of Choice tends to cast the desire for commitment as ‘loving too much’ – that is, loving against one’s own self-interest. Although enough broken-hearted men are pathologised for their ‘neediness’ and ‘inability to let go’, it is mostly women who fall into categories of ‘co-dependent’ and ‘immature’. Across class and race, they are trained to make themselves self-sufficient – to ‘not love too much’, to just ‘celebrate themselves’ (per the The Rules, above).

The trouble is, a bubble bath cannot substitute for a loving gaze or a long-awaited phone call, let alone make you pregnant – whatever Cosmo might suggest. Sure enough, you can have IVF and grow into an inspiringly mature, wonderfully independent single mother of thriving triplets. But the greatest gift of love – the recognition of one’s worth as an individual – is an essentially social matter. For that, you need a significant Other. You’ve got to drink a lot of Chardonnay to circumvent this plain fact.

But perhaps the greatest problem with the Regime of Choice stems from its misconception of maturity as absolute self-sufficiency. Attachment is infantilised. The desire for recognition is rendered as ‘neediness’. Intimacy must never challenge ‘personal boundaries’. While incessantly scolded to take responsibility for our own selves, we are strongly discouraged from taking any for our loved ones: after all, our interference in their lives, in the form of unsolicited advice or suggestions for change, might prevent their growth and self-discovery. Caught between too many optimisation scenarios and failure options, we are faced with the worst affliction of the Regime of Choice: self-absorption without self-sacrifice.

Where I come from, however, we have the opposite problem: self-sacrifice often comes without much self-examination at all. Julia Lerner, an Israeli sociologist of emotions at Ben Gurion University of the Negev, recently conducted a study into the ways that Russians talk about love. The purpose of her research was to find out whether, as a result of the post-communist, neo-liberal turn, the gap between Seventeen magazine and the Tolstoy novel had finally started to close. The answer is: not really.

Having analysed discussions in various TV talk shows, conducted interviews and done content analysis of the Russian press, she established that, to Russians, love remains ‘a destiny, a moral act and a value; it is irresistible, it requires sacrifice and implies suffering and pain.’ Indeed, whereas the concept of maturity that lies at the heart of the Regime of Choice regards romantic pain as an aberration and a sign of poor decision-making, the Russians consider maturity to be the capacity to bear that very pain, sometimes to an absurd degree.

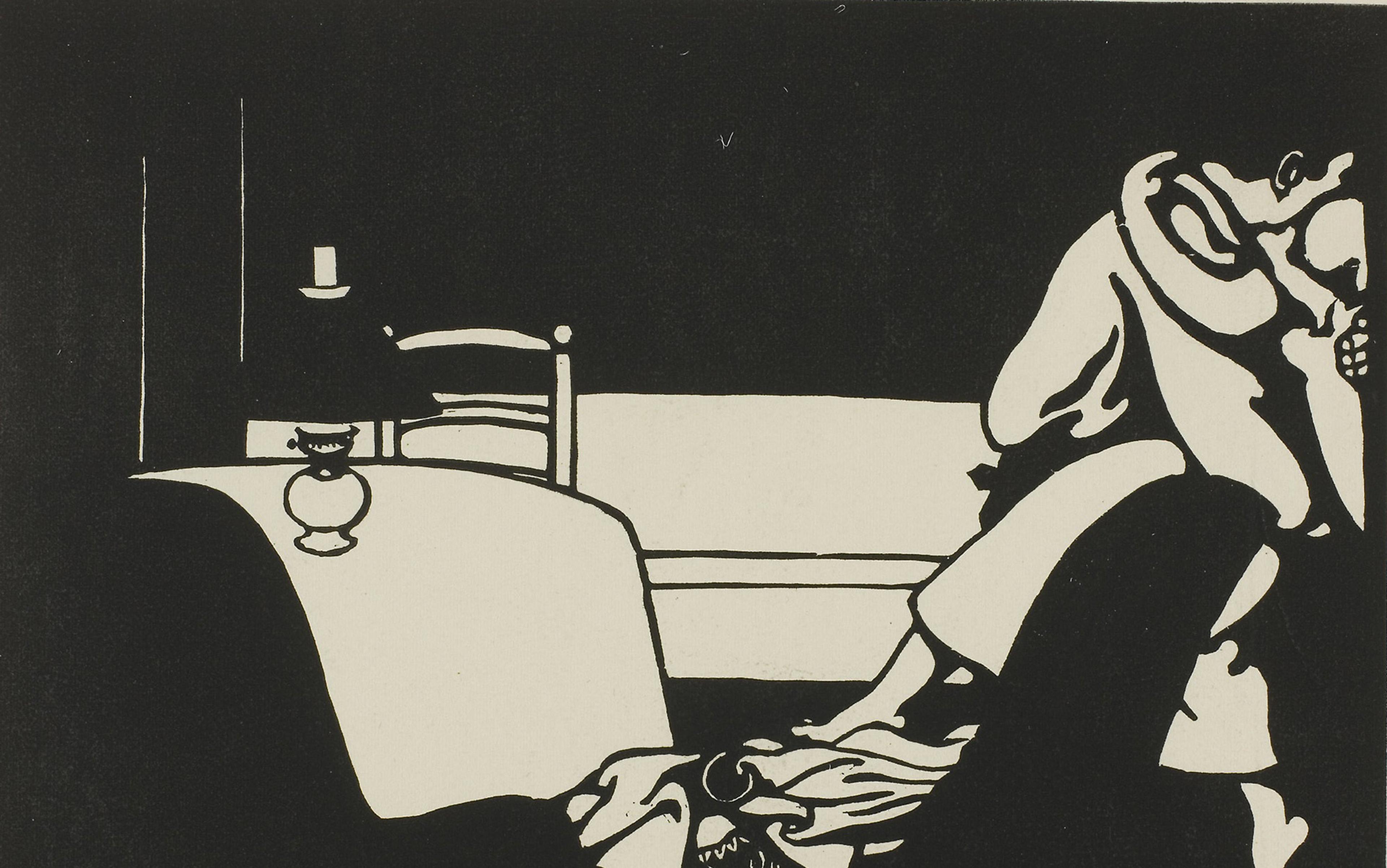

A middle-class American who falls in love with a married woman is advised to break up with the lady and to schedule 50 hours of therapy. A Russian in a similar situation, however, storms the woman’s house and pulls her out by the hand, straight from the hob with stewing borsch, past crying children and a husband frozen with game controller in hand. Sometimes, it goes well: I know a couple who have been together happily for 15 years since the day he had kidnapped her from a conjugal New Year’s feast. But in most cases, the Regime of Fate produces mess.

In terms of bulk numbers, Russians have a greater number of marriages, divorces and abortions per capita than any other developed country. These statistics document an impetus to do whatever it takes to act upon emotions, and often at the cost of one’s own comfort. Russian romance is closely accompanied by substance abuse, domestic violence and abandoned children: the by-products of lives that were never really thought‑through very clearly. Apparently, believing in fate each time you fall in love is not such a great alternative to excessive choice.

But to solve the afflictions of our culture, we do not need to give up on the principle of choice altogether. Instead, we must dare to choose the unknown, to take uncalculated risks and be vulnerable. By ‘vulnerability’ I do not mean the coquettish exposure of weaknesses meant to test the compatibility between you and your date. My plea is for existential vulnerability, for the re-mystification of love into what it essentially is: an unpredictable force that usually catches you unawares.

So. Make loud love proposals. Move in with someone before feeling completely ready for it. Have a child when the timing seems bad

If the understanding of maturity as self-sufficiency is so detrimental to the way we love under the Regime of Choice, then it is precisely this understanding that needs to be reconsidered. To become truly adult, we need to embrace the unpredictability that loving someone other than ourselves entails. We should dare to cross those personal boundaries and run one step ahead of ourselves; not at a Russian pace, maybe, but just slightly quicker than we are used to.

So. Make loud love proposals. Move in with someone before feeling completely ready for it. Grumble at a partner for no reason and have that person grumble back, just like that, because we are human. Have a child when the timing seems bad. And finally, we need to re-claim our right to pain. Let us dare to agonise about love. As Brené Brown, a sociologist studying vulnerability and shame at the University of Houston, suggests, perhaps ‘our capacity for whole-heartedness can never be greater than our willingness to be broken-hearted’. Rather than obsessing over the integrity of our selves, we need to learn to give parts of that self to others – and acknowledge, finally, that we are dependent on each other, even if a Seventeen columnist might call it co-dependent.