Does biology determine destiny, or is society the dominant cause of masculine and feminine traits? In this spirited exchange, the psychologist Cordelia Fine and the evolutionary biologist Carole Hooven unpack the complex relationship between testosterone and human behaviour.

Fine emphasises variability, flexibility and context – seeing gender as shaped by social forces as much as it is by hormones. By contrast, Hooven stresses consistent patterns; while acknowledging the influence of culture and the differences between individuals, she maintains that biology explains why certain sex-linked behaviours persist across cultures.

At stake in this debate is how we understand ourselves and organise our communities. Can we achieve equality by changing cultural norms, or must we accommodate biological realities that evolution has inscribed in our brains? As you read, notice how these scholars interpret the same evidence through fundamentally different frameworks – revealing why discussions about sex differences remain both scientifically complex and politically charged.

Cordelia Fine:

Risk-taking, dominance, aggressive jostling for status – many of us are familiar with the idea that these masculine traits can be largely chalked-up to testosterone. Take this description of the dangerous, male-dominated environment of an oil platform in the 1980s, where one worker compared his colleagues to ‘a pack of lions’:

The guy that was in charge was the one who could basically out-perform and out-shout and out-intimidate all the others. That’s just how it worked out here on drilling rigs and in production. So those people went to the top, over other people’s bodies in some cases.

But then something changed. In the early 1990s, the company overhauled their policies and practices on the rig to enhance safety and effectiveness – and, in doing so, inadvertently created an environment that ‘released’ these men from displays of masculinity.

This unexpected effect was documented by the organisational scholars Robin Ely and Debra Meyerson, who observed the pattern play out on two offshore oil platforms. For the first time, workers started to acknowledge their own physical limits, admit their mistakes, and discuss their own and others’ emotions. A deck mechanic sent a classical music tape home for a coworker’s baby, saying that ‘it’s real important for them babies to listen to music like that. Real soothing.’ When a researcher tipped his chair back in a meeting, he was politely told: ‘That’s not safe.’ Men openly displayed fear when evacuated after 9/11. ‘We are a very different group now than we were when we first got together – kinder, gentler people,’ one production operator said.

No part of the company’s strategy involved dispensing androgen blockers to change levels of testosterone in men’s bodies. But it did involve a change of organisational culture. The focus was on collective goals, admitting and learning from errors, and disentangling notions of competence from displays of machismo. Asked to reflect on what being a man meant to them, the workers ended up describing manliness in non-stereotyped ways, often drawing on ideas of approachability, compassion and humility.

This case study belongs to a robust body of evidence that makes me sceptical of the significance of testosterone. Sceptical, that is, that this hormone is the root cause of the many gendered differences in behaviour that we see in humans.

Let me take a step back, and describe what I call ‘Testosterone Rex’. This is my tongue-in-cheek phrase for the seductive, seemingly undefeatable notion that men and women have distinct natures, in large part due to the basic, powerful, pervasive and direct effect of testosterone. In this account, ‘T’ becomes the potent, hormonal essence of competitive, risk-taking masculinity.

Testosterone Rex appears in many forms. Its starting point is what the anthropologist Sarah Blaffer Hrdy has called the ‘coy female’ paradigm – the idea that asymmetries in what it costs females versus males to have babies make males more motivated by mating success. Males potentially invest as little as a sperm, while females contribute a nice plump egg and, in mammals, full bed-and-board in utero and lactation. Over evolutionary time, this means males will develop traits that help them fight for access to females, and appear more appealing to females browsing for their next mate. Testosterone furnishes both the physical and behavioural traits.

This popular Testosterone Rex story is too simple. Both evolution and testosterone allow for a much greater diversity and flexibility of sex roles than previously (and popularly) appreciated – especially in humans.

The concept of the ‘developmental system’ can help us grasp this flexibility. The idea here is that creatures don’t just inherit genes, but also ecological, social and (in our own case) cultural legacies. These are all inherited resources. Evolution can ‘use’ stable, non-genetic legacies, in addition to genetic ones, to make sure that behavioural adaptations develop and get passed on across generations.

Along with our genes, we inherit our rich, cumulative cultures

Take the California mouse, where, unusually for mammals, both parents care for their offspring. Fathers’ tendency to ‘huddle and groom’ their babies is influenced by testosterone in an interesting way: castration reduces paternal care, while testosterone replacement restores it. Moreover, sons raised in a family unit with castrated, less involved fathers went on to show less pup huddling and grooming themselves when they became fathers (despite being ‘intact’). This all suggests that an organism’s environment and experiences can be a stable, inherited resource, contributing to the lifelong development of adaptive traits.

A unique aspect of human developmental systems are our rich, cumulative cultures, which we inherit along with our genes. Thousands of years of gendered cultures, together with our evolved and unparalleled capacity for social learning, might have reduced the need for genes to be the ‘carriers’ of sex-linked behavioural features. Instead, as John Dupré, Daphna Joel and I have suggested, these traits could stabilise through norms that tell us what it means to be a woman or a man, and that are transferred across generations. If a male California mouse reliably inherits a father who will huddle and groom him, that’s a developmental resource that doesn’t have to be redundantly locked into genetically inherited biology. And if a male human reliably inherits a rich gendered culture that provides ample information and instruction about how to be man, along with minds tuned to acquire, enforce and internalise those norms, there’s much less need for genetic mechanisms to enforce the development of gendered traits, beyond a neural capacity for learning.

Such cultures come about in response to the pressures of particular times and places in our evolutionary history – which means we can and should modify them when circumstances require, as we’ve always done. On the developmental systems view, changing the environment (something at which humans obviously excel) can change the expression of masculine and feminine behaviour, without the need for millennia of slow genetic change.

This all points to the fact that testosterone isn’t the ‘essence’ of masculinity. My target here isn’t the crude and patently false idea that all men are like this, and all women are like that. It’s the notion that, amid all the noise of individual differences, we can extract a male ‘nature’ that is somehow natural, immutable, and driven by testosterone.

Does this mean that I think humans are completely unaffected by hormones, including testosterone? Of course not. But even in nonhuman animals, testosterone is just one variable in a complex system, one of many factors that feeds into an animal’s decision-making. Social context and experience can override T’s influence on behaviour, or even stand in for T’s absence. Moreover, T responds to contexts and situations, helping us adapt to them. This means that how much T a body has, and how it reacts to it, are inextricably intertwined with the individual’s history and experience – including, in our own case, the influence of gender norms.

I could go on, but I know you take quite a different line, Carole. Thank you for being open to unravelling our disagreements together. These points of divergence about sex differences are often attributed to politics but, in my view, they have far more to do with the conceptual frameworks people bring to the evidence.

Carole Hooven:

Cordelia, you represent the idea that testosterone explains a lot about human sex differences as ‘T-Rex’: a dinosaur that gets it wrong, and should die, never to rear its head again. I agree that T-Rex is a complicated beast; but he has many moments of clarity where he gets the science basically right. And I will do what I can to keep that more sensible T-Rex alive.

We do agree on some things – such as the value of reproductive autonomy, a world free of the threat of male violence, and flexibility of gender expression. I also agree that one’s environment profoundly affects behaviour. I (like every other biologist) don’t think sex differences in behaviour are immutable or invariant, or that testosterone can create sexed ‘essences’ or ‘natures’ that separate the behaviour of the sexes into two discrete categories.

Our substantive disagreements are about the origins of sex differences. You see testosterone as one variable in the complex system of human behaviour. I see unambiguous evidence that it can account for some of the large and extremely impactful differences between men and women, particularly when it comes to sexual psychology and aggression.

Let’s go back to the case study of men on an oil rig. The authors described the change in stereotypically masculine behaviour, catalysed by workplace policies, as ‘undoing gender’. If such behaviour is the result of evolutionary forces, with high testosterone carrying out their orders, then ‘gender’ should be resistant to undoing. That is, how could the men soften so dramatically without hormone blockers? This seems like very strong evidence against my claims. Shouldn’t I just throw in the towel right here?

Well, no. Workplace changes on the oil rigs reduced stereotypically masculine behaviour in men; but this doesn’t undermine the view that differences between the sexes in traits like aggression (or anything else) originate in differences in inherited biology. Let me explain with an example. Imagine you’re trying to enjoy a meal at a fancy restaurant, but are distracted by a toddler at the next table screaming and banging silverware. Such disruptive behaviour is common among young children. However, if you go out to dinner in Japan or France, you’re likely to notice that the little diners are more restrained than their counterparts in the US. That’s not due to differences in innate biology; instead, it’s due to the fact that kids, like the rest of us, can modify their behaviour in response to incentives. This is despite having what we might think of as a distinct ‘nature’ – that is, different behavioural predispositions on average – from adults.

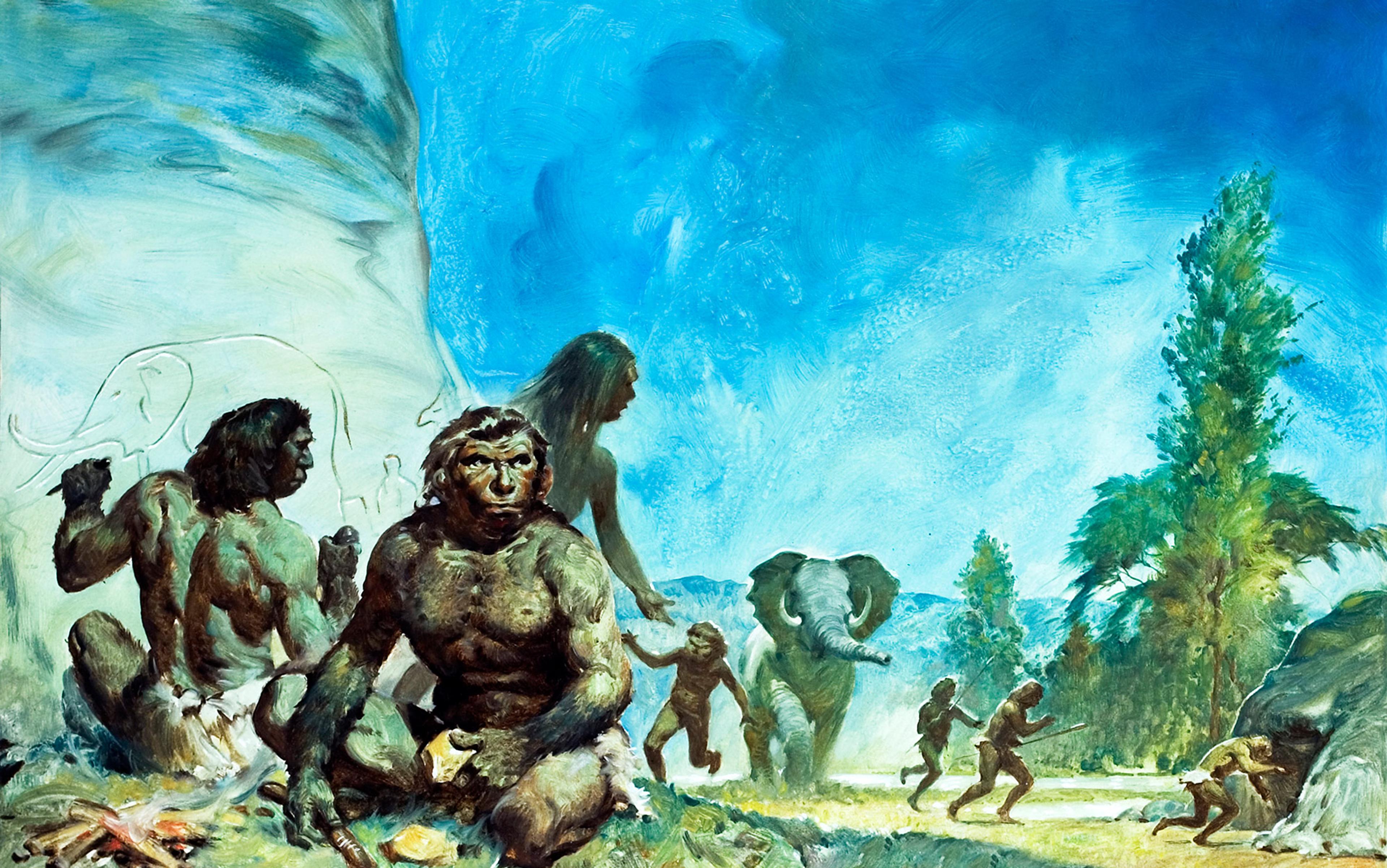

To establish dominance, male elephant seals will bite and ram each other with their huge bodies

What I’m trying to explain is not whether culture influences aggression in men, but why, across cultures, men are more aggressive than women in the first place. This is a pattern that varies in form and extent, but rarely reverses.

To flesh out my view, I should say a few words about sexual selection – a form of natural selection in which traits that help animals attract mates and reproduce are passed on at relatively high frequency to future generations. Males tend to reap higher reproductive rewards from successfully competing for mates. That means sexual selection tends to be stronger in males, though it acts on females too. This leads to the evolution of more pronounced traits in males that promote mating competition, such as brighter colours, stronger bodies, or a higher propensity for aggression.

Sexual selection in male elephant seals is notoriously strong. They compete intensely for control of beaches where females come to give birth and mate. To establish dominance, they will bite and ram each other with their huge bodies, which can weigh up to 4 tonnes (around four times the average weight of females). The battles can go on for hours, but successful dominant bulls, identifiable by the cuts and scars on their chests, will mate with dozens of females who will bear their pups. Higher testosterone in males is a major tool, the proximate mechanism, for developing and regulating many of these traits, including making sperm, which all support reproduction. So, when it comes to behavioural sex differences, testosterone is not simply a variable in a complex system; on the contrary, its actions, shaped by sexual selection, are often the key drivers.

This doesn’t mean that men spend their lives trying to tear each other apart. We are not a highly polygynous species like the elephant seal, in which lots of fierce aggression is a sensible reproductive strategy. All animals use aggression judiciously, but it depends on the costs versus the rewards for particular animals in a given environment. And the same is true for us. In humans – who are arguably mildly polygynous – individual proclivities for aggression vary widely, but males still have a heightened propensity for it. Given enough alcohol, an honour-based culture, the right kind of threat or the ready availability of guns, it will show itself.

Cordelia, your work emphasises the indirect effects of testosterone on behaviour via bodily changes and gender socialisation. For example, male-typical levels produce a big, strong, bepenised body, which then influences how others treat you – expecting ‘masculine’ behaviour, being granted social status, or access to food or mates. These experiences in turn shape psychology and brain development, reciprocally interacting with testosterone.

That’s all true; but it is completely consistent with the robust scientific evidence that testosterone has a direct and tremendously meaningful effect on behaviour via the brain too – an idea that you criticise strongly. But sexual selection would not sculpt males with bigger, stronger bodies if it hadn’t also selected for psychological traits that leveraged this strength to bring sperm to egg.

Testosterone is what coordinates sperm production with the vastly complex physical and psychological traits that are necessary to get sperm to egg, and when advantageous, to invest in one’s mate and offspring after that. In men, testosterone directs the development of primary reproductive traits such as the genitalia, and secondary sexual features such as muscularity and a deep voice. The hormone is in an excellent position to tell the brain what the body is up to – such as whether sperm is currently being made or fertile females are available, such that males are motivated to do what’s necessary to mate when that effort will pay genetic rewards.

There are many complexities in how sexual selection and testosterone shape human sex differences. But they don’t merit killing off the more sensible versions of T-Rex entirely.

Cordelia Fine:

Let me recap what I understand your position, and the ‘sensible’ T-Rex approach, to be. Stronger sexual selection on males gave rise to masculine physical and psychological traits that facilitate male competition for mates, status and resources. Testosterone ties all this together, making it ‘the hormone that dominates and divides us’, as you’ve written in your 2021 book.

On this view of things, the imbalance in how much males and females must invest to reproduce – which becomes particularly marked when you throw in gestation and lactation in mammals – is the key to understanding sex roles across the animal kingdom. Maleness, here, becomes a sort of ‘essence’ that determines specific behavioural predispositions of the male sex role. You’ve mentioned bull seals, and in your book you wrote about male red deer, male mountain spiny lizards, male Syrian hamsters and male chimpanzees. As you frame it, they all seem to possess this kind of ‘essence’, and so will develop to have those ‘masculine’ predispositions.

So how could humans, with our nine-month pregnancies and long periods of breastfeeding on one side of the ledger, versus one measly sperm on the other, be any different? The answer is: because there are many exceptions to this pattern across the animal kingdom, both across species and within them.

Our divergent perspectives likely stem from the different lenses we’re using: you prioritise cross-species tendencies, while I focus on documenting variability, and am interested in what that could mean for humans.

Sex is indeed important for explaining the evolution of mating systems. But it’s part of a diverse picture

Let’s go back to the ‘coy female’ idea, which is more politely described as the Darwin-Bateman paradigm. It dates back to foundational empirical research with fruit flies by the biologist Angus Bateman in the mid-20th century. But the paradigm has come under significant criticism in the scientific community. Statistical reanalysis and critique have contested Bateman’s conclusions. Meanwhile, evolutionary biologists have learned more about phenomena such as the reproductive benefits to some species’ females of promiscuity and status, and the non-trivial costs to males of sperm production and distribution. Even among primates, purported universals like the link between male dominance and reproductive success are better understood as general patterns rather than immutable laws. There is good evidence that sexual selection varies not only between but also within species, as a function of demography and environment. Some biologists even advocate for radical ‘sex-neutral’ models of sex roles – proposing that mating behaviour is determined by probabilistic, random processes, as well as ecological, social and demographic conditions, and that sex plays no role.

To be clear, I disagree with those radical sex-neutral models. I don’t view the Darwin-Bateman paradigm as obsolete. The evidence suggests that sex is indeed an important concept for explaining the evolution of mating systems. But it’s part of a remarkably diverse picture, pointing to multiple ‘counter-forces’ that can push against the evolution of conventional sex roles, as my colleague John Dupré has argued.

An important takeaway of this diversity of sex roles across species is that we need to be cautious when generalising findings to humans. Every species has its own evolutionary history when it comes to solving the problem of reproduction, and our own evolutionary pathway is a unique one – not least the cumulative culture and social learning I mentioned before. On my account, cultural norms don’t just ‘dial up or dial down’ evolved traits. They can help to construct them in the first place.

So whither testosterone? On my account, gender and other social constructions are not an alternative explanation to internal mechanisms of sexual selection such as hormones; they are additional mechanisms, and often work together. If our culture tells us that a man’s honour is everything, a man’s testosterone will rise when he is insulted by a stranger. But if he was raised with different masculine norms, his testosterone levels will remain unchanged. If hands-on fathering is a norm, more men will be active carers for their young children – an activity associated with declines in testosterone levels.

Our social worlds intersect with our biology. Testosterone’s impacts are not pre-programmed by evolution but guided by the meanings humans attach to behaviours, dynamically tuning behaviour within a cultural framework. This is profoundly different to the T-Rex idea that gender norms can either ramp up or ramp down an evolutionarily ‘intended’ behavioural outcome.

Carole Hooven:

Cordelia, your response opened with your take on my view, beginning with the ‘sensible’ T-Rex version: that ‘the imbalance in how much males and females must invest to reproduce … is the key to understanding sex roles across the animal kingdom.’ So far, so good. This is a claim that I enthusiastically endorse, and which you think is one that should be killed off; so here we have a strikingly clear point of disagreement. We’re getting somewhere!

You acknowledge that sex is an important variable for understanding mating, and you don’t endorse radical sex-neutral theories. But then you take T-Rex (and me along with him) head-first into straw-man territory. This is where maleness is described as ‘a sort of “essence” that determines … predispositions of the male sex role.’ What serious biologist thinks this? My view is that the sexes are born (on average, as always) with different predispositions, leading to what are called ‘traditional sex roles’, which T-Rex gets right. This pattern, of females being more nurturing and males being more competitive, applies to our own species.

For instance, men’s strength and relative reproductive freedom makes it easier for them to take physically demanding jobs that require long stays away from home, while women might take more work inside the home in order to be closer to, and nurse, young children. So, while a gendered culture influences how these traditional roles play out, I don’t see the evidence that it imposes them.

Of course, science also tells us the many fascinating stories of ‘non-traditional’ sex roles! Some men aren’t interested in mating with women, and some transition to living in a female social role. Others are peace-loving devoted fathers and husbands. I wouldn’t presume that these men are repressing a predisposition to be bellicose womanisers.

Sex roles are influenced by the most basic division of labour: making eggs or making sperm

And then there are what we might call the ‘sex-reversed’ species, which Charles Darwin discussed in The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871). One example that comes to mind is the shorebird known as the red-necked phalarope, in which the males do nearly all of the parenting, while females are larger and brighter, and compete aggressively for mates.

Red-necked phalarope hatchlings, Alaska. Photo by Emily Weiser/USGS/public domain

It’s exceptions like the phalarope that prove the rule: for the sex that invests the least in parenting, competition for access to mates is often more fierce than the other way around. That results in greater sexual selection pressure operating on the less investing parent, producing physical and behavioural strategies for out-competing each other for access to mates.

Other than having a body plan to produce small gametes, there is no ‘male (or female) essence’. There are no ‘intended’ sexed-natures. There are, however, sex roles that are influenced by the most basic division of labour: making eggs (investing more in parenting) or sperm (investing more in competing for mates). That initial division has resulted in the evolution of traditional sex roles. Bateman’s theory was correct (although his research was flawed): promiscuous mating does, on average, yield greater reproductive benefits for males than females. The fact that there are many exceptions to and variation in those roles – especially in our own species – is not a reason to believe that we are exceptions to the general rule. What makes us exceptional is that, regardless of our biological impulses, we can reflect on, and even discuss, what we believe and how we want to behave.

Perhaps we could zoom in to look at the case of aggression in more depth. I’d love to know if you agree with the consensus view of evolutionary biologists: that testosterone, given its evolutionary instructions by sexual selection, drives higher rates of aggressive competition in male mammals. If we agree on this, then we can focus on whether the same principles and processes apply to humans.

Cordelia Fine:

Your question illustrates the differences between our approaches. You work from the frame that there is a general ‘principle’ that testosterone drives sex differences in aggression in mammals. You expect humans to conform to that principle, and interpret the weak and ambiguous evidence from humans on the relationship between hormones and aggression through this lens.

In contrast, I am interested in the diversity we see across species, and the reasons to expect humans’ capacities for social learning and culture to play a key role in development and evolution. From this frame, the absence of clear evidence (despite decades of attempts to find it) for associations between physical aggression and testosterone exposure – prenatally, at puberty, or any changes post-puberty – is telling us something important.

We should always be cautious not to treat sex-correlated patterns as a ‘general rule’, including the related assumption that sex always gets its ‘work’ done in the same way across species. (The California mouse, mentioned earlier, is a nice example of a surprising evolved role for testosterone.) We know that the mechanisms that bring about an adaptive behaviour in species A may be quite different to the causes that bring about the same behaviour in species B.

For example, research on mice clearly shows testosterone’s causal role in male aggression – it increases at puberty, castration reduces it, and injections restore it. However, as the aggression researchers John Archer and Justin Carré note, ‘the neuroendocrine control of aggression is different in a number of the species that have been studied.’ Different species do things differently. In humans, some scientists have shifted towards models in which changes in testosterone adaptively tune competitive or nurturing responses to relevant contexts. Moreover, human social structures and cultural norms both construct and give meaning to these contexts. Recall the offshore oil platform – does status and respect come from dominance, or from being open, honest and willing to listen to coworkers? The general point is that we need to be very careful about generalising across species, and we need to account for the specificity of their developmental systems – beyond genes and hormones. Our own developmental systems are rich in social constructions of gender that interact with ‘self-socialising’ tendencies.

My argument is not with evolutionary biology but with essentialist thinking creeping in via the back door

I agree that there are strong sex-correlated patterns across species. One influential meta-analysis of 66 animal species, for example, found that sexual selection was stronger on males than females as a whole – but also noted many exceptions, and acknowledged the role of ecological and demographic factors. In some human populations, these conditions meant sexual selection was similarly strong on both sexes. Whichever way sexual selection leans, it surely operates via a range of mechanisms that respond to social, material and physical conditions – and, in the case of humans, economic and cultural ones. And since the development and transfer of adaptive traits relies on the entire developmental system, not just the genes, relevant changes in non-genetic features of the system can bring about significant shifts in gendered behaviour.

That’s why the question of whether male promiscuity, risk-taking and competitiveness were sexually selected adaptations for reproductive success simply doesn’t have the implications for now and the future that we usually assume they do. Nor does it necessarily mean that a hormonal endowment prefigures the male brain for these traits (although that’s not to deny the likelihood of sex-differentiated initial ‘tilts’).

A final important note about this idea of ‘essences’. I appreciate that contemporary evolutionary biologists recognise the diversity of mating systems, and don’t think of sex as an essence that underpins a ‘natural law’ across the animal kingdom of coy females and competitive males. But my argument is not with contemporary evolutionary biology. My objection is with the T-Rex view, in which essentialist thinking creeps in via the back door.

For example, it’s clear in your response to the oil platform case study that you regard the men’s earlier stereotypically masculine behaviour as somehow more ‘natural’ than their behaviour post-intervention. Such sex differences, you say, ‘originate’ in inherited biology, which culture can only influence. To explain the expression of more feminine traits in these men, you offer the analogy of the ‘distinct “nature”’ of children being tempered with incentives.

You and I both agree that there’s variation in behaviour among the sexes and overlap between them. The disagreement concerns how to explain these patterns. The famously essentialist philosopher Aristotle accounted for variation in nature as the combined product of underlying natural tendencies and interfering forces of various degrees and kinds. In other words, distinct natural tendencies can nonetheless give rise to plenty of overlap in phenotype. Translated to sex differences in behaviour, this doesn’t seem so different from the views you expressed on Joe Rogan’s podcast:

My book T is not trying to explain why males are one way and females are another way, but why we’re different on average, why we have somewhat different natures, and testosterone is to me the most powerful way to understand those differences in our natures.

So, while you might think I’m taking aim at a straw man, I am targeting a view held by you and others that, under the veil of variation within and overlap between the sexes, testosterone is an essence that underpins male nature – making men what they are, while cultural forces can only attempt to interfere with or derail it.

Carole Hooven:

I closed my last response by asking whether you agree ‘that testosterone, given its evolutionary instructions by sexual selection, drives higher rates of aggressive competition in male mammals.’ I then suggested that, if we agree on this, we can focus on whether those ideas apply to humans. If we disagreed, then we could have examined why.

Instead of answering my question, you chose to engage with an ‘essentialist’ version of T-Rex, rather than my own views. Ideally, I would reply to your comments and cautions about the science, as well as correct the record, but I have space only for the latter.

You said my question revealed a ‘general principle’ that I supposedly endorse, and to which I expect humans to conform: that testosterone drives sex differences in aggression in mammals. But I worded my question to you carefully, so that we could pinpoint our areas of disagreement. I do endorse the idea that testosterone drives the sexes apart in many ways in many species, but that’s quite different from holding a blunt ‘general principle’ that I apply across the board to all sex differences in all mammals. It’s true that mammals provide clear examples of how and why sexual selection tends to act more strongly on males, and that, in those cases, testosterone drives the expression of those sexually selected adaptations for male mating competition. However, as for the existence of a general principle that testosterone drives sex differences in mammalian aggression (rather than driving higher rates of aggressive competition in male mammals, as I wrote), that is not what I argue. For example, in my book T, I describe species such as naked mole rats, hyenas and meerkats, in which females are often more aggressive than males. In these cases, sex differences in testosterone don’t clearly predict sex differences in aggressive behaviour.

What is ‘stereotypical’ in one environment may not be in another: men might express more vulnerability in Canada than in Russia

If I did operate from the general principle you describe, and if I expected that principle to apply to humans, your repeated cautions about overgeneralising and failing to appreciate diversity would be warranted. But, again, this isn’t how I think, nor have written or taught (for more than 20 years) about hormones and behaviour. As I described in T:

Unlike rats, our genes are expressed within the context of a complex cultural environment, interwoven with diverse norms and practices that significantly affect the behaviour of interest. We live in a culture that often requires us, explicitly or implicitly, to conform to gender norms in one way or another. So of course we still need to test our hypotheses on humans to draw any firm conclusions about how we work.

I do, however, generate evidence-based hypotheses, and make predictions about outcomes.

Next, you’ve created a narrative based on my opening comments – about the oil rig case study and my analogy about young diners – that appears to provide evidence for my ostensible belief in ‘distinct’ male and female ‘natures’, sexed ‘essences’ and some masculine behaviours being more ‘natural’ than others. These simply are not my positions. If you read back over my replies, you’ll see I wrote that kids may have a ‘distinct “nature” – that is, different behavioural predispositions on average – from adults’ (italics added). I hope I was clear that cultural norms can modify how behavioural predispositions are expressed. This means not just that kids can learn to behave in restaurants, despite being different from adults. It also means that what is ‘stereotypical’ in one environment may not be in another; for example, women fleeing violence might be more stoic than when safe in the suburbs with their families, and men might express more vulnerability in Canada than Russia. It’s not clear which behaviour should be considered more ‘natural’. What’s interesting and deserving of explanation is why, when it comes to behaviours such as risk-taking, violence or emotional expression, the sex difference is almost always in the same direction.

You then go on to draw links between my views and those of the ‘famously essentialist’ philosopher Aristotle, quoting something I said to Joe Rogan. Here I say that I’m trying to explain why we’re different on average, and why we have somewhat different natures.

What all this adds up to is that I don’t hold the essentialist views about sex that you ascribe to me. In order to understand why that’s the case, we should be on the same page about how you define such views. Here’s one example, from your book Testosterone Rex (2017):

Amid all the ‘noise’ of individual differences, a male or female ‘essence’ can be extracted: characteristics of maleness and femaleness that are natural, immutable, discrete, historically and cross-culturally invariant, and grounded in deep-seated, biological factors.

To be clear about my actual view of how biology and culture interact to produce sex differences, consider parental care. Men tend to do less overall, but the magnitude of the sex difference varies widely across cultures and historical periods. The existence and direction of the behavioural differences may be due to ‘deep-seated, biological factors’, but culture heavily influences how those differences play out.

You say you’re not aiming at a straw man but rather the position you ascribe to me: that testosterone is an essence, that it underpins male nature, and that it makes men what they are. This would require accepting that every testosterone-typical man has the ‘male essence’, and so also the ‘male nature’, which presumably involves an aggressive predisposition. And that is simply not my view.

Cordelia Fine’s conclusion:

Not all species have evolved ‘traditional’ sex roles; environment and culture shape human behaviour; and not all men behave in stereotypically masculine ways. The fact that Carole and I agree on these things isn’t surprising. Understanding our disagreements requires digging deeper.

In this dialogue, Carole has denied that she thinks that testosterone ‘makes men what they are’. Yet in her recent TED talk, she stated that prenatal testosterone ‘made my son who he is today’.

Carole says that no ‘serious biologist’ thinks that maleness determines the predispositions of the male sex role. Yet in an opinion piece for The Boston Globe this February she wrote that: ‘Despite the vast natural variation among individuals, one constant stands out: sperm producers compete – often fiercely – for access to egg producers, while egg producers invest more in parenting …’ In this dialogue, what she calls ‘“sex-reversed” species’ are exceptions that prove the rule.

Carole says that testosterone ‘drives higher rates of aggressive competition in male mammals’ – including humans. As she puts it, sex differences ‘in traits like aggression (or anything else), originate in our differences in inherited biology’. Yet, according to her, this causally potent and ubiquitous hormonal force leaves only some men with a predisposition to aggression (setting aside whether or not it is expressed).

Unlike any other mammal, we have evolved to socially construct gender roles

It seems clear that T-Rex essentialism is no straw man, even if he is sometimes shy about showing himself.

Sex does indeed help us understand why, across species, some sex differences are more common than others. But the diversity of sex roles is an equally salient fact. This diversity reflects the many innovations evolution has found to help species reproduce – innovations that, in humans, include our capacities for cooperation, social learning and cultural transmission across generations.

Testosterone and other hormones do help us adapt to conditions and contexts. But human exceptionalism goes well beyond ‘cultural norms [that] can modify how behavioural predispositions are expressed’, or self-reflectiveness about ‘our biological impulses’. Any scientific explanation of sex differences in behaviour must take seriously the idea that, unlike any other mammal, we have evolved to socially construct gender roles, as my most recent book [Patriarchy Inc.: What We Get Wrong About Gender Equality and Why Men Still Win at Work (2025)] explores.

Consider: why is male violence against women rare among Aka Pygmies? Why is same-sex adolescent fighting more than eight times more common in boys in some lower-income countries (such as Tunisia and Suriname) but equally common among boys and girls in others (such as Tonga and Ghana)? Why do only 4 per cent of Swedish males follow a developmental trajectory leading to violent crime, while the remaining 96 per cent do not?

These are the kinds of questions we should be asking if we are serious about addressing male violence. T-Rex will not help us find the answers.

Carole Hooven’s conclusion:

What explains differences in male and female behaviour? The answer involves a complex mix of environmental and biological factors, including gender socialisation, genes and hormones. On this, Cordelia and I largely agree, and I’ve been grateful for the opportunity to discuss it all with her.

Cordelia opened this dialogue with a case study about men on an oil rig, illustrating the kind of evidence that’s made her ‘sceptical that [testosterone] is the root cause of the many gendered differences in behaviour that we see in humans.’ Such evidence, she claims, reveals that testosterone is ‘just … one of many factors that feeds into an animal’s decision-making,’ rather than being ‘the essence … of masculinity’. She says that I ‘take quite a different line’.

Boys tend to play more roughly than girls, even though young children’s testosterone levels don’t differ much

But I don’t take a different line. Of course testosterone isn’t the male essence. And of course the hormone isn’t the only factor guiding behavioural decisions in humans or any other animals. Countless interacting factors – like health, marital status, local laws – affect our decisions, like whether to throw a punch in response to an insult. Yet across the diverse influences – physical, social and psychological – men are more likely to behave violently. Culture certainly plays a role here; but there is no denying that humans are far from the only animals in which males are more aggressive than females, and that testosterone is, at a minimum, strongly associated with those patterns. All of this, especially couched within the framework of sexual selection, implicates testosterone as a key player in human sex differences. Cordelia has offered no strong hypothesis that explains the fact that, across time and place, men are more likely than women to decide to throw that punch.

What role does testosterone play, then? It acts on the male body and brain during critical developmental periods – in utero, around birth, and during puberty – with effects on behaviour that often show up down the road. Boys tend to play more roughly than girls, even though young children’s testosterone levels don’t differ very much. Scientists believe that higher testosterone in fetal males drives this preference, as it does in other mammals. Violent crime, which is overwhelmingly committed by men, doesn’t peak when testosterone peaks in the late teens; instead, it peaks in men’s 20s, the phase of life when size, strength and competition for mates are at their highest. The existence of the paternal California mouse, as well as emotionally sensitive, high-testosterone human roughnecks, is entirely compatible with the hormone driving sex differences in aggression. An evolutionary perspective can help to make sense of these patterns.

If, as I believe, testosterone drives some important sex differences, this shouldn’t deter us from pursuing a safer, more just society. The solution lies in harnessing the power of culture, rather than altering our genes and hormones. An openness to the strongest evidence, and to learning all we can about how genes and environment interact to produce behaviour, can only help.

Killing off T-Rex entirely serves only to shoot ourselves in the foot. Behavioural endocrinology and evolutionary theory provide powerful, time-tested frameworks for understanding sex differences in humans and other animals. Keep a sane T-Rex alive!