The Oscar Wilde Temple first opened in 2017, in the basement of the Church of the Village in Greenwich, New York. Wilde is glorified on a plinth: a creamy statue dressed as a dandy, his prison number from his time served in Reading Gaol, C.3.3, on a sign below him. Directly behind Wilde is a large neo-Gothic stained glass window of Jesus, drawing an association of martyrdom between the two men. On the walls there are also pictures of LGBTQ figures who were similarly persecuted: Alan Turing, Harvey Milk, Marsha P Johnson. The artwork was created by David McDermott and Peter McGough.

This is a depiction of Wilde that we are all familiar with: as a flamboyant aesthete and gifted writer, a witty provocateur who is supposed to have told customs officials in New York, ‘I have nothing to declare but my genius’, who wrote sparkling plays and splendid children’s books. He might have married the writer Constance Lloyd, but this was clearly a smokescreen to conceal his true sexuality, for he had numerous affairs with men, from Robbie Ross to Lord Alfred Douglas. Wilde’s blossoming talent was destroyed by a cruel Victorian public who vilified him for his homosexuality and flung him into prison, causing him to die in poverty and misery in a Parisian bedsit a few years after his release. Subsequently, over the past 50 years, Wilde has been adopted by the LGBTQ movement as a secular saint, the ultimate symbol of a persecuted gay man.

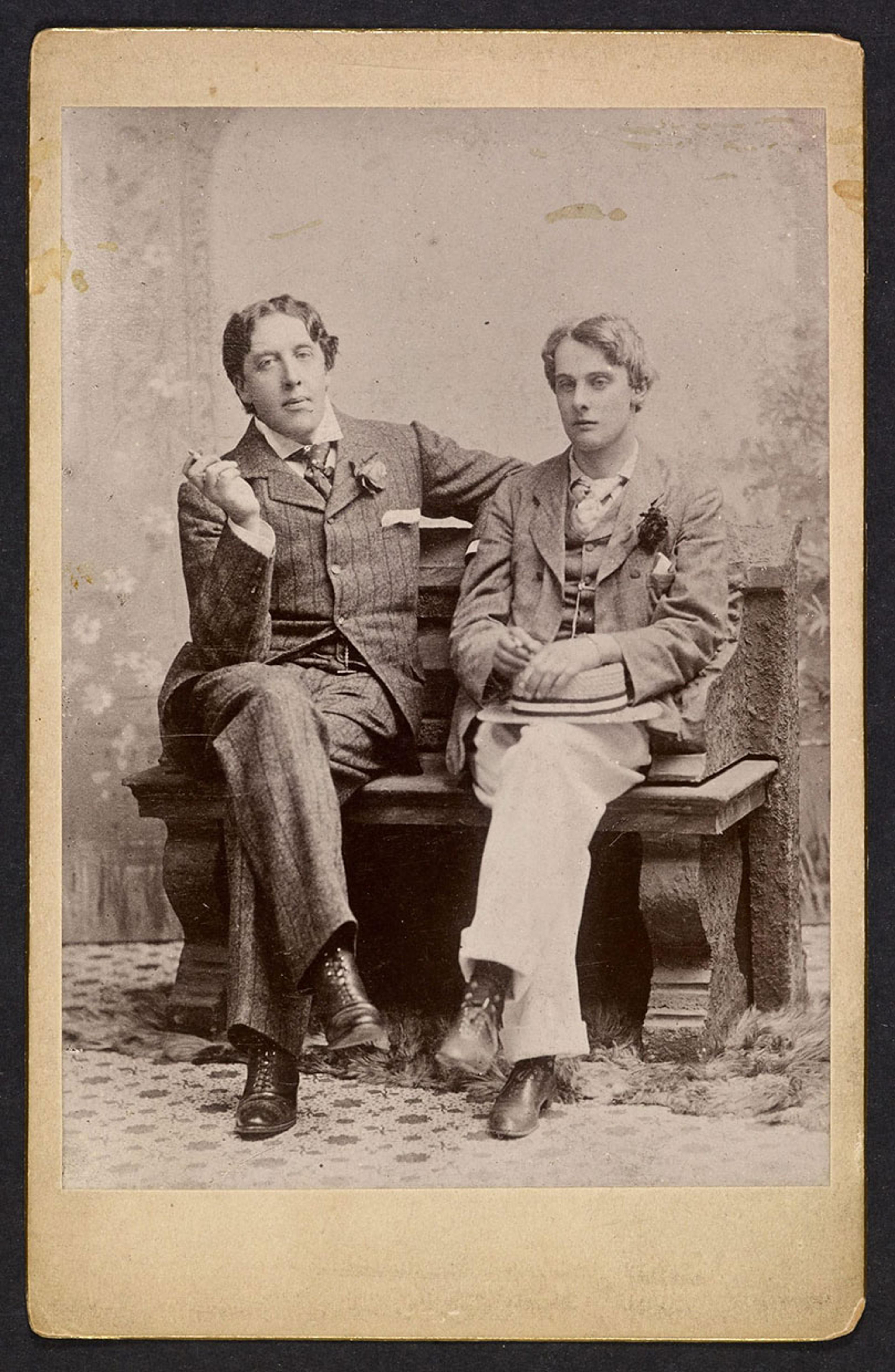

Oscar Wilde with Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas, c1893 Courtesy the British Library

But is Wilde’s story as simple as this? Is this a fair representation of his life and sexuality? Wilde was, after all, a man of contradictions. Shortly before he died, he confided in Jean Dupoirier, the proprietor of the Hôtel d’Alsace, that: ‘Some said my life was a lie but I always knew it to be the truth; for like the truth it was rarely pure and never simple.’ In ‘Biography and the Art of Lying’ (1997), Merlin Holland, Wilde’s grandson, points out that Wilde’s life is not one that ‘can tolerate an either/or approach with logical conclusions, but demands the flexibility of a both/and treatment, often raising questions for which there are no answers.’ Those who have attempted to mould Wilde to their own agenda, simplifying his complexities, have soon found that ‘he turns to quicksilver in their fingers’.

Wilde’s reputation as a gay martyr stems from his prosecution in 1895 for ‘acts of gross indecency’. It was one of the first ‘celebrity’ trials of the century. Wilde was at the peak of his career. He had plays running in the West End that were roaring successes, including The Importance of Being Earnest. He had been married to Lloyd for 11 years and they had two children, Cyril and Vyvyan. It was an open secret that Wilde was having a love affair with Lord Alfred Douglas, the son of the Marquess of Queensberry. Lord Alfred had introduced Wilde to the sexual underground, where they would rent young men for sex. Several confrontations took place between Wilde and the Marquess, who was a volatile and angry man; Wilde denied any sexual relations with his son. Then, in February 1895, Wilde entered the Albemarle Club to find a card had been left for him by Queensberry, with the scrawled accusation: ‘To Oscar Wilde posing Somdomite’ [sic].

The spelling mistake may have been deliberate, as well as the use of ambiguous language, which would make it easier to win a case if Wilde sued. Nevertheless, it was a trap that played on the Victorian need for masks of heterosexual respectability. To simply look like a sodomite, in a society that had rigid ideas about gender, was a risky situation to be in. Wilde decided to take Queensberry to court, not to defend himself as a homosexual passionately fighting a cause – but to clear his reputation. He assured his barrister, Sir Edward Clarke, that the charges were ‘absolutely false and groundless’.

The trial was a key moment in the evolution of the shaping of sexuality – whether hetero or homo – as an identity. Prior to the Victorian era, sex was a practice, not an identity. The Victorians introduced the Offences Against the Person Act in 1861, which removed the death penalty for sodomy, but created a new punishment: 10 years to life penal servitude. In 1885, the Labouchere Amendment, which introduced the vaguely worded crime ‘acts of gross indecency’, meant that two men could be taken to court for simply exchanging a few love letters, with no witnesses needed. It is no wonder that it became known as the Blackmailer’s Charter.

The libel case collapsed and suddenly Wilde found that he was now the one on trial

The criminalisation of homosexuality went hand in hand with attempts to classify it. Victorian sexologists such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing perceived homosexuality as a pathology, a deviation that stemmed from arrested development. Others argued that those suffering from the ‘illness’ were ‘inverts’: ie, men committing homosexual acts were female souls born into male bodies, and vice versa. A growing public hostility to inversion was accompanied by a collective curiosity: what were the characteristics of a man who loved men? How did he dress? How did he behave? In the UK in 1870, two men, Ernest Boulton and Frederick William Park, were arrested for dressing as women, and a doctor was asked to examine them for physical ‘signs’ of homosexuality – but he admitted that he was not sure what he was looking for. As the journalist Eric Berkowitz notes in Sex and Punishment (2012), it was ‘a critical early effort’ at defining what characteristics a gay man might have.

The Liberal MP Lord Arthur Pelham-Clinton with Frederick William Park (aka Fanny, standing) and Ernest Boulton (aka Stella, who called herself Clinton’s wife). Courtesy Frederick Spalding/Essex Record Office

In later decades, inverts came to be seen as predators. In 1889, the Cleveland Street Scandal erupted, where a number of teenagers working as telegraph boys at the General Post Office were revealed to be moonlighting as rent boys at Cleveland Street, a brothel frequented by wealthy individuals such as Lord Somerset and the Earl of Euston. The scandal filled the tabloids week after week. The boys were seen as innocents; public ire was aimed at the older men who procured them. A year later, when Wilde published The Picture of Dorian Gray, a novel ripe in homoerotic undercurrents, it was slated in The Scots Observer as a story that would be of interest mainly to ‘outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph-boys’ – a jibe that referenced Cleveland Street.

When Wilde took the libel case against Queensberry to court, he underestimated the danger he was in. In part, it was a matter of class: he didn’t believe that the reports of the lower-middle-class witnesses Queensberry had called would be taken seriously. On the first day of the trial, he turned up in a horse-drawn carriage, sporting an overcoat trimmed with velvet, and answered the prosecution’s questions with flippant wit. When asked if he had kissed Walter Grainger, aged 16 at the time, Wilde replied: ‘Oh, dear no. He was a peculiarly plain boy.’ As more young men were brought to the stand, describing lavish gifts that Wilde had given them to entice them into sex, the libel case collapsed and suddenly Wilde found that he was now the one on trial, unfairly portrayed as the dark corruptor of golden boy Lord Alfred.

As the prosecution closed in on him, Wilde gave a speech that many applaud as the first by a homosexual publicly defending his sexuality (in fact, that honour ought to go to the German sexology pioneer Karl Heinrich Ulrichs in 1867). Nevertheless, Wilde’s speech was beautiful and heartfelt:

‘The Love that dare not speak its name’ in this century is such a great affection of an elder for a younger man as there was between David and Jonathan, such as Plato made the very basis of his philosophy, and such as you find in the sonnets of Michelangelo and Shakespeare. It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect.

For Wilde never described himself as a homosexual, nor an ‘invert’. Having studied Classics at Oxford, he saw his sexuality in the tradition of pederasty, a practice dating back to ancient Greece and Rome where an older man would play sexual guide and intellectual mentor to a younger boy. He favoured the term ‘Uranian’, coined by Ulrichs in the 1860s, derived from Plato’s Symposium. Some critics, however, feel that Wilde’s speech was a way of romanticising an exploitative situation: some of the boys he slept with were half his age, and they also suffered the trauma of exposure and humiliation during his trial.

Once imprisoned, Wilde wrote a letter to the Home Secretary pleading for pardon, declaring that he was suffering from ‘erotomania’ and ‘a monstrous sexual perversion’. Writing online for The Imaginative Conservative in 2018, Joseph Pearce went as far as to cite the above examples as proof that Wilde was a ‘homophobe’. But consider the horrors that Wilde faced once he entered prison. He was made to pace a treadmill for hours each day, pick oakum, sleep on a plank, his latrine a metal bucket. He developed an ear infection and became terrified of losing his hearing. Meanwhile, his name had been stripped from theatre playbills, his family home ransacked due to the debts he owed. Therefore, I think Wilde’s retractions were symptomatic of despair, of him being ground down by a system that had wrecked his health, happiness and marriage.

Out of prison, Wilde’s attitude changed entirely. The Daily Chronicle printed a letter by Wilde arguing fiercely for improving conditions in prisons and the need to ‘humanise the governors’. He wrote to the prison reform campaigner George Ives that: ‘I have no doubt we shall win, but the road is long, and red with monstrous martyrdoms. Nothing but the repeal of the Criminal Law Amendment Act would do any good.’ In fact, if Wilde is to be celebrated as a defender of gay rights, then this, I believe, is his greatest moment of bravery: after fleeing to France, he soon reunited with Lord Alfred and they lived in Naples together. Wilde was denied seeing his children, his wife threatened to cut off his funds, and he and Lord Alfred suffered constant social rejection: in a hotel in Capri, English guests walked out in disgust at the sight of them the dining-room and they were both asked to leave the hotel.

Wilde’s trial was so legendary that it shaped our modern ideas of how a gay man should be. In the 1906 edition of Sexual Inversion – one of the first English medical textbooks – the sexologist Havelock Ellis argued that the Wilde trials ‘generally contributed to give definiteness and self-consciousness to the manifestations of homosexuality’. Writing in The Guardian in 2024, the novelist Tom Crewe reflected that Wilde’s ‘scandalous exposure created a set of public assumptions and prejudices that persisted for well over half a century, often twisting how gay people saw themselves’ – such as ‘the belief that gay men, like Wilde, imposed themselves on the world by their difference: that they dressed differently, talked differently, were “theatrical”. That their relationships were … crudely sexual, exploitative, mired in inequalities of age and class.’

Crewe also argued that Wilde’s trial obscured the birth of a potential gay rights movement that was taking place in the 1890s, spearheaded by the abovementioned Ellis, as well as the writer Edward Carpenter and the poet John Addington Symonds. Carpenter, for example, was working on a pamphlet, Homogenic Love and its Place in a Free Society, that was subsequently rejected by his publisher. In 1897, Ellis published Sexual Inversion, which sought to demonstrate that homosexuality was a customary, recurrent element of human sexuality. The book was deemed ‘lewd, wicked’ and ‘scandalous’ and Ellis’s editor, George Bedborough, was prosecuted for selling ‘obscene libel’. Meanwhile, following Wilde’s trial, 600 men, fearing they might suffer similar prosecutions, fled across the English Channel.

Plays such as The Importance of Being Earnest were reinterpreted as gorged with homosexual subtext

For decades to come, Wilde’s name would be associated with disgrace and furtive homosexual longings. In E M Forster’s novel Maurice, written in 1913, the titular character sees himself as ‘an unspeakable of the Oscar Wilde sort’. In the 1960s, Wilde began to be adopted by gay rights campaigners. In 1967, Craig Rodwell, a member the Mattachine Society, an early gay rights organisation in the US, opened the Oscar Wilde Memorial bookstore in Greenwich Village. Rodwell saw Wilde as ‘the first homosexual in modern times to defend publicly the homosexual way of life, [he] is a martyr to … the “homophile movement”.’ After the Stonewall Riots of 1969, the bookshop became instrumental in helping to set up the Pride marches that became a yearly tradition. In 1964, Susan Sontag dedicated her essay ‘Notes on “Camp”’ to Oscar Wilde.

As the LGBTQ rights movement gathered pace, Wilde’s reputation as a gay icon and martyr was cemented. Previously, academics had been encouraged to ignore any gay undercurrents in Wilde’s work; now an entire industry sprang up examining coded references to homosexuality in his writing. There are certainly homoerotic undertones in The Picture of Dorian Gray – which Wilde had to tone down from the serialised magazine version to its book publication. However, plays such as The Importance of Being Earnest were soon reinterpreted as being gorged with homosexual subtext: for example, ‘bunburying’ – after the fictitious ‘invalid’ Bunbury whom Algernon uses to get out of unwanted social engagements – was seen as code for living a double existence, or a marriage concealing a secret gay life. ‘Earnest’ has also been interpreted as a code word for gay, a twist on ‘Uraniste’, based on the term used by Ulrichs, but Holland has refuted this, pointing out that if it had been the case then it would have been used against Wilde in his trial.

Writing in The Wilde Century (1994), Alan Sinfield says that many of these interpretations are simply superimposed onto the text:

Many commentators assume that queerness, like murder, will out, so there must be a gay scenario lurking somewhere in the depths of The Importance of Being Earnest. But it doesn’t really work … Wilde and his writings look queer because our stereotypical notion of male homosexuality derives from Wilde, and our ideas about him.

But does Wilde really stand up as a gay icon? A common misconception about him is that he was homosexual from a young age and his marriage was a mask. However, in an interview with The Advocate magazine in 2008, Holland asserted that his grandfather married for love, and that his sexuality was complex: ‘If it was a black-and-white story of Oscar just being homosexual from the year one and concealing it and finally coming to terms with it, it would make a much less interesting story,’ concluding that, as a gay icon, Wilde is ‘flawed’.

In fact, it is hard to label Wilde as a gay man at all when you consider his history of passionate crushes on, and relationships with, women. When studying at Oxford, Wilde was reprimanded by the mother of a student, Fidelia, after he was caught kissing her. In 1878, he dedicated his award-winning poem ‘Ravenna’ to the writer Julia Constance Fletcher, declaring that ‘she writes as cleverly as she talks’ and he was ‘much attracted by her in every way.’ The first woman he hoped to marry, Florence Balcombe, he lost; on meeting her in 1876, Wilde wrote to a friend enthusing: ‘She is just seventeen with the most perfectly beautiful face I ever saw and not a sixpence of money.’ Six months into their relationship, he gave her a beautiful gold cross with his name engraved on it. When a rival, Bram Stoker (who would later write Dracula), married her two years later, Wilde was heartbroken.

Oscar, Constance and Cyril Wilde, photographed at the end of their holiday in Felbrigg in Norfolk, UK, summer 1892. Courtesy Wikipedia

Wilde married Constance Lloyd in 1884, a year before ‘acts of gross indecency’ were criminalised in the UK. It is hard, therefore, to argue that he felt forced to marry to conceal his gay leanings. When Oscar and Constance first met during the summer of 1881, there was an immediate frisson between them. Constance’s mother, Ada, saw that they were a good match, writing to Lady Wilde that ‘both are … charming, gifted and what is to my mind even more essential to the beginning of married life, immensely attracted to each other.’ During their six-month engagement, they exchanged numerous telegrams and letters. ‘We are of course desperately in love,’ Wilde wrote to his friend Thomas Waldo Story. ‘[W]e telegraph to each other twice a day, and the telegraph clerks have become quite romantic in consequence.’ When their first son, Cyril, was born in 1885, Wilde wrote to the actor Norman Forbes-Robertson that his son was ‘wonderful’ and enthused about the joys of matrimony, encouraging him to marry ‘at once!’

He enjoyed affairs with men in part because they were a delicious rebellion against a society he loved and loathed

But, after a few years of marriage, Wilde began to grow restless. He lost his desire for Constance when she became pregnant with their second child, preferring her ‘white and slim as a lily’. In 1886, the 17-year-old Robbie Ross came to stay with the Wilde family as a house guest, and Wilde enjoyed his first gay love affair when Ross ‘seduced’ (Wilde’s words) his host.

That his marriage turned sour is too often held up as proof that Wilde really was gay – for example, in The Secret Life of Oscar Wilde (2005), Neil McKenna asserts that their marriage was ‘passionless’. But many marriages fail, often for complex and numerous reasons, and while Wilde’s attraction to his wife did fade, this is not particularly unusual or shocking. In Constance (2012), Franny Moyle argues that they married (as many Victorians did) without knowing each other well, and that marriage, the process of discovering each other, brought both intimacy and disillusionment. Furthermore, Moyle speculates that ‘there may have been post-natal medical issues on Constance’s side’ causing sex to wane between them. It is a mistake to assume that Wilde’s marriage was a sham and that the second act of his sexuality defines him absolutely, so that his past is rewritten to fit this narrative.

Because one aspect of Wilde’s desire was forbidden, it cleaved his sexuality into two distinct halves with opposing characteristics: one half respectable, one rebellious; ‘one Apollonian, one Dionysian’, in the words of the biographer Richard Ellmann. Wilde enjoyed love affairs with men in part because they were forbidden, a delicious rebellion against a society he loved and loathed. ‘[T]he danger was half the excitement,’ he reflected later, in prison. ‘I used to feel as a snake-charmer must feel when he lures the cobra to stir from the painted cloth …’ Male lovers became associated with decadence, marriage with duty, men with the underground, his wife with the acceptable surface.

Ellmann saw Wilde’s shift from female to male lovers as a ‘reorientation’. I would argue that a more accurate term to describe Wilde’s sexuality was that he was bisexual. Interviewed in Marjorie Garber’s Vice Versa (1995), the academic Jonathan Dollimore reflected similarly: ‘My feeling about Oscar Wilde is that he was certainly bisexual, and there is a sense in which I do deplore that representation of Wilde as living entirely in bad faith in relation to his wife.’ However, gay theorists have resisted this more complex and nuanced examination of Wilde’s sexuality. Take these words from the queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, interviewed in Outweek magazine in 1991: ‘I’m not sure that because there are people who identify as bisexual there is a bisexual identity …’ The interviewer goes on to summarise that: ‘In questioning whether bisexuality is a potent identity, Sedgwick points to historical figures the gay and lesbian community claims as lesbian and gay (Cole Porter, Eleanor Roosevelt, Virginia Woolf, Walt Whitman, Oscar Wilde) – who would actually be classified as bisexual,’ to which Sedgwick concludes: ‘But the gay and lesbian movement isn’t interested in drawing that line.’

The trouble with Sedgwick’s argument is that it reinforces a simplistic homo/hetero binary. The result is that – as Steven Angelides points out in A History of Bisexuality (2001) – ‘bisexuality… is unthinkable outside of binary logic’ and hence becomes erased. However, this diminishment of bisexuality was characteristic of the era. From the 1970s onwards, bisexuals have historically found their sexuality ignored or dismissed, and had to fight for decades for the ‘B’ to be included in LGBTQ. Bisexuality has frequently been seen as a phase or situated ‘on the fence’, where the sitter will inevitably come down on one side or the other, or deemed as a dilution of a cause; lesbian feminists in the 1980s were suspicious of bi women who were seen as ‘sleeping with the enemy’ and, in 1985, the London Lesbian and Gay Community Centre banned bis because their lesbian members felt threatened by bisexual men. During the AIDs crisis, bis were frequently scapegoated, depicted as the bridgeway between two sexual populations, passing the disease from gay to heterosexual and back again.

Because bisexuality has been mischaracterised as a sort of ‘no man’s land’, where it has always been harder to fight a cause, Wilde’s sexuality was inevitably simplified. The binary story of Wilde as an innocent persecuted gay man versus a cruel heterosexual public is a more potent one, particularly given the alarming rise in LGBTQ hate crimes this century. In 2016, the arts organisation Artangel organised a public reading in Reading Prison of De Profundis – the letter Wilde wrote while incarcerated – with luminaries such as Ralph Fiennes, Lemn Sissay and Maxine Peake reading sections aloud. When interviewed, one of the directors, Michael Morris, noted that, in some countries, being gay is still illegal: ‘We want people to be mindful of that oppression and persecution.’

This is certainly a good reason to remember the horrors of Wilde’s fate. However, to accept that Wilde was bisexual does not mean that his gay inclinations are halved or half-hearted, or that his tragedy is diluted. It does not diminish the cruelty of Victorian society in condemning him to spend two years in a dark, freezing cell, his mind suffering a slow shattering, his genius going to waste simply because he did not conform to their narrow idea of what sexuality should be. But it does acknowledge that he was a much more complex figure than the misleading caricature that theorists’ agendas and social causes have slowly shaped him into.