In Plato’s dialogue Symposium, seven varied speeches are made on the meaning of love at an all-male drinking party set in ancient Athens in 416 BCE. One of the participants is the philosopher Socrates, and when it comes to his turn to speak, he is made to say something surprising: he proposes to ‘tell the truth’ about love. It’s surprising because in other Platonic dialogues, where Socrates addresses questions such as ‘What is knowledge?’, ‘What is excellence?’, and ‘What is courage?’, he has no positive answers to give about these central areas of human thought and experience: in fact, Socrates was well known for having laid no claim to knowledge, and for asserting that ‘the only thing I know is that I do not know’. How is it, then, that Socrates can claim to know the truth about something as fundamental and potentially all-encompassing as love?

The answer is that, in the Symposium, Socrates claims to know the truth only because he learned it from someone else. He describes his teacher of love as a ‘clever non-Athenian woman who had knowledge of this and many other things’ (my translations throughout). He gives her name as Diotima of Mantinea, and appears to endorse unquestioningly the account of love that he learned from her, which he now proposes to present to his audience.

It is generally supposed that this instructor is a Platonic fiction: the figure of Diotima is often called a ‘priestess’ thanks to the wisdom and authority with which she speaks (though no such designation is given by Plato). But what is at stake for our understanding of Socrates’ thought if we accept as true his claim that he learned about love from a woman? And what might we learn about the meaning of love?

Here I will first outline the ‘truth about love’ imparted by Diotima to Socrates. I will then explain why we might suppose that Diotima was based on a real person, Aspasia of Miletus, and suggest what this might mean for our understanding of Socrates’ thought and philosophical procedure. In accepting that Plato has sought to connect Diotima to an exceptional and well-known historical figure, we can gain new insights into a neglected biographical influence on Socrates, and into how his method of definitional enquiry developed. That method was to provide the crucial foundation for Plato’s approach not just to understanding love, but to creating his metaphysical theory about of the transcendent nature of truth and reality.

The doctrine Socrates attributes to Diotima in the Symposium is that love – or, more precisely, the divine spirit Eros – operates on various levels. At the lowest level, love engenders erotic feelings towards the body of someone to whom one is attracted. However, what attracts us about that body is, Diotima says, a quality that we call its ‘beauty’, which in turn leads to a recognition that many other bodies possess this quality and are equally capable of inspiring erotic feelings. By recognising the presence of beauty in many bodies, one comes to understand that what is attractive to us is not the bodies themselves, but the abstract quality of beauty of which the bodies partake.

This leads to the further insight that things other than bodies possess beauty: we are attracted to non-corporeal things such as, most importantly, ‘wisdom, laws and institutions’ – the features of a community or city that command a citizen’s love and loyalty. In this way, according to Diotima, the commonplace erotic desire that we feel towards a person we consider to be beautiful can lead us up the ‘ladder’ of love, rung by rung, ascending from the particular object of desire to a general appreciation of the abstract quality of beauty and, beyond that, to moral goodness. What begins as physical lust is ennobled by the way it encourages the lover to mount upwards to the highest goodness imaginable, the abstract ‘form of the good’.

Aristophanes spins a brilliant fantasy about love being the force that drives one to seek one’s ‘other half’

This notion of the transcendent aim of love seems strange and mysterious even to Socrates, we are told. Diotima explicitly characterises love as a ‘mystery’ into which listeners have to be initiated, just as initiands were initiated into the Mysteries (the arcane cult observances of Greek gods such as Dionysus). However, the rungs of the ladder that represent the stages of the lover’s ascent are prefigured in the dialogue by the five speakers who precede Socrates. Each of them describes a commonly acknowledged aspect of love (at least, commonly acknowledged in their time). But each of them offers only an incomplete understanding: as in the story of the blind men trying to describe an elephant – one feels the trunk, and says an elephant is like a snake; another touches the flank, and says it’s like a wall – each of the partygoers gives only a partial account of what will add up, by the end of the dialogue, to a more complete picture.

The first of the speakers, a young aristocrat called Phaedrus, takes physical relationships for granted in arguing that Eros gives lovers the urge to act nobly, to the point of even being prepared to die for those they love. The second speaker, Pausanias, makes explicit the distinction between sexual gratification and the more honourable form of love that involves lifelong commitment and spiritual interconnection. The physician Eryximachus then speaks of love as an abstract, harmonising force that operates in the body, in music, and in nature as a whole. The tragedian Agathon rounds off the speeches by praising with florid extravagance love’s artistic and creative power, which he claims gives rise to eloquence and literary inventiveness.

Just before Agathon speaks, the comic playwright Aristophanes spins a brilliant fantasy about love being the force that drives one to seek one’s ‘other half’ in order to make us feel complete and whole. He invents a myth about ‘original humans’ being duplicates of what we are today – roly-poly creatures with two faces, four arms, four legs (and so on). These beings were too powerful and self-satisfied, he says, to be allowed to continue as they were, so Zeus split them in half to create human beings as we know them. But the result of that split is that we are constantly seeking to return to our original wholeness by seeking to unite with our ‘other half’; and that desire, says Aristophanes, is love.

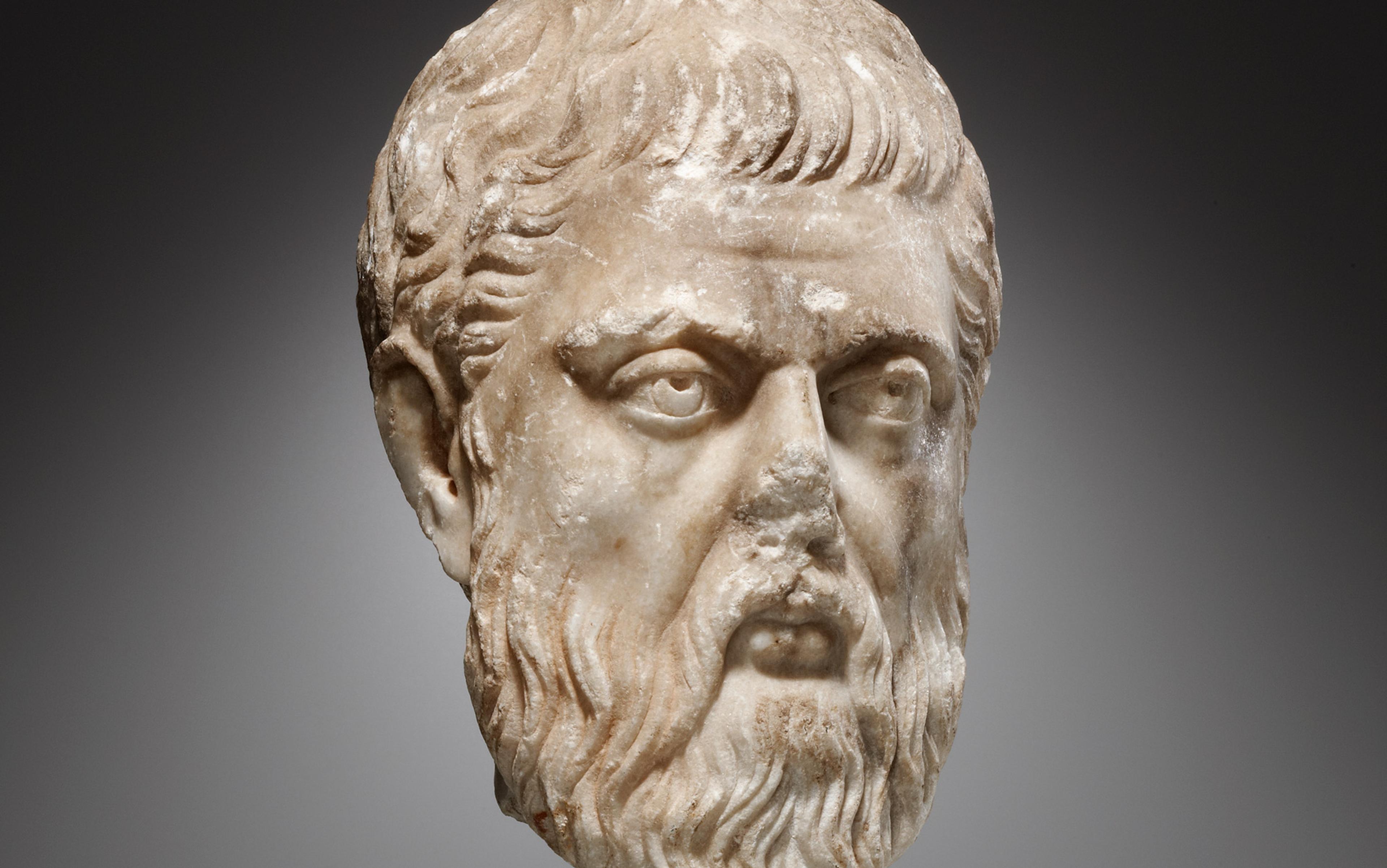

Socrates identifies the person who taught him this doctrine of ascent as Diotima. The woman who ‘taught me the ways of Eros’, he says, was a foreign woman (in Greek xenē, ie, non-Athenian), whom he heard speak about love on more than one occasion in the past. ‘Diotima’ is not independently attested in the historical record, but the curiously specific details with which Socrates introduces her make a compelling case that she is at least partly based on a real woman: Aspasia of Miletus. Aspasia was the wife of Pericles, the leading citizen of Athens, the general and statesman associated with the ‘Periclean Age’ of Athenian efflorescence, who wielded political leadership for 30 years until his death in the Great Plague in 429 BCE. The comic poets Eupolis, Cratinus and Aristophanes, the equivalent of the tabloid commentators of today, regularly lambasted Aspasia’s influence over Pericles and her alleged involvement in affairs of state.

In introducing the figure of Diotima, Socrates remarks that ‘she postponed the plague by 10 years, when Athenians were making sacrifices to avert it’. Scholars have been remarkably unconcerned to track down the implications of this very specific statement. Why should the Athenians have been sacrificing, evidently at a woman’s instruction, a decade before the plague struck in 430-429 BCE? The date points the alert reader to the infamous campaign waged 10 years earlier, against the island of Samos by Pericles, the Plague’s most prominent victim. Aspasia’s influence was popularly suspected in Pericles’ decision to attack the island, which was a commercial and military rival to her native city Miletus. The conquest of Samos was marked by notable callousness on the part of the Athenian aggressors. During the campaign, Samian prisoners were branded like cattle and, after Pericles eventually subdued the island by land and sea, he ordered that the enemy commanders be crucified in the main square of Miletus, their bodies thrown out without burial.

His actions will have been the cause of grave alarm to his fellow Athenians and supporters, and no less to Aspasia. To deny burial even to an enemy was sacrilege, and likely to incur the gods’ wrath. The tragedian Sophocles served as a general on the Samian campaign: in his play Antigone, produced the following year, the chorus speaks about the ritual pollution (miasma) of an unburied enemy’s body for which the city has been punished by a god-sent plague. In that play, the dead Polyneices has been condemned as an enemy of the state, and his burial has been expressly forbidden by the city’s leader Creon (meaning ‘ruler’). Polyneices’ sister Antigone (a name that in Greek has the same number and shape of syllables as ‘Aspasia’) contrives to bury him, arguing that it’s a religious duty, and stressing that Polyneices is her kinsman. The duty towards kin is echoed in an episode reported in Plutarch’s biography of Pericles, wherein the general was criticised on the grounds that his success on Samos had meant the deaths of ‘kindred Greeks’ rather than barbarians.

Pericles was known to accord Aspasia conspicuous respect, even embracing her in public

Divine retribution for Pericles’ sacrilegious conduct on Samos, likely in the form of a plague, will surely have been feared by Athenians in 439 BCE. One recourse was to appease the gods by prayers and sacrifices. Plato’s statement suggests that such actions did take place in 439 BCE; and the fact that no plague transpired may well have led Athenians to suppose that these expiatory measures had averted the expected divine punishment. Ten years later, however, when the plague struck Athens, killing Pericles among tens of thousands of others, it will have dawned on them that due punishment for his actions had not been averted, only postponed. If sacrifices were conducted in 439 BCE, as stated in the Symposium, at the behest of a ‘clever woman’, the instigator and overseer can have been none other than Aspasia, Pericles’ famously clever and protective wife.

The intended allusion to Aspasia is reinforced by Plato’s choice of the name Diotima, which means ‘honoured by Zeus’. Zeus was the chief of the Olympian gods, and the comic poets lampooned Pericles as ‘Zeus’ because of his dominant status and thundering oratory (they also referred to Aspasia as ‘Hera’, Zeus’s wife). Pericles was known to accord Aspasia conspicuous respect, even embracing her in public, an unusually honorific gesture in the strongly patriarchal Athenian society. His liaison with Aspasia dates to around 450 BCE, when he was in his mid-40s and she in her 20s. Having divorced his first wife some years earlier, Pericles had become infatuated with the exotic, clever ‘foreigner’ after she arrived in Athens from Miletus in Asia Minor, accompanying her sister, the wife of Alcibiades, grandfather of the notorious playboy-politician of that name.

The comic playwright Aristophanes’ mention of ‘Zeus’ will have evoked an image of Pericles in the minds of many readers. A further resonance may be heard when Aristophanes speaks of Zeus splitting the ‘original’ human beings. The biographer Plutarch tells the story of how a ram with a single horn in the centre of its forehead was once brought to Pericles from his country estate. This phenomenon was interpreted by a seer as a sign that Pericles would hold sole political power in Athens. However, after Pericles ordered the skull to be split in half, it was discovered that the ram’s brain had developed defectively, leading the horn to emerge at a single point. Aristophanes’ image of two halves seeking union after being split into two conjures up this detail of Pericles’ experience.

A lost contemporary account of Aspasia quoted by the Roman orator Cicero shows that she was recognised for her cleverness and eloquence. She established a salon in Athens (perhaps in the home of her brother-in-law Alcibiades, who would have been her required male sponsor) where she is said to have ‘instructed elite Athenians including Socrates on amatory matters’. In this respect, she could be compared to the respected itinerant teachers called ‘Sophists’ – the very term applied to Diotima in the Symposium. Diotima’s talks on matters of love, which Socrates says he heard on more than one occasion, chime with the description we are given by the Roman statesman Cicero, drawing on a source contemporary to Socrates, of Aspasia’s sessions: on one occasion, she advises a married couple that their relationship should rest on a mutual respect of the other’s moral qualities. This ethical approach resonates with the doctrine espoused by Diotima whereby true love, though starting in the physical realm, ultimately ascends to moral virtue.

That love of transcendent beauty is the culmination of what Diotima calls the ‘greater mysteries’. But prior to entering that realm, the elevation of the soul to ‘loving good order and the operation of justice’ is offered as the final stage of the lesser mysteries. ‘Up to this point, Socrates,’ Diotima says, ‘even you might be initiated. But the aim of these rites, correctly performed, is to reach the final vision of the mysteries. I’m not sure you could manage that, but I’ll explain them to you and you must do your best to follow.’ This is a distinguishing moment in Diotima’s speech. Why should Plato make Diotima suggest that Socrates might be inadequate to understand what follows?

The reason must be that this marks the point at which Diotima’s doctrine ceases to resemble the kind of thing either Aspasia or Socrates might have said or conceived. The doctrine thereafter moves into realms of metaphysics that neither could in their time have been aware of, for the simple reason that the ideas now introduced involve Plato’s own subsequently developed notion of the forms. It thus becomes clear why Plato could not name Aspasia directly as the author of the full doctrine that Socrates attributes to Diotima. In principle, such an attribution would have been possible: in another dialogue, Menexenus, Plato confidently presents Aspasia by name as a teacher of eloquence to both Pericles and Socrates. But, in this case, he would have been keenly aware that the latter half of the doctrine that he puts into the mouth of Diotima – the greater mysteries – was an exposition of nothing other than his own idiosyncratic conception of the forms. As Aristotle was later to insist, Socrates himself had no part or interest in formulating such a theory. The forms were Plato’s own solution to positing a stable, unchanging realm of reality, a metaphysical answer to the question of how such qualities as justice, beauty, courage and wisdom might exist without change or qualification.

Plato knew, however, that for an account of a symposium set in Socrates’ own time and supposedly representing Socrates’ thought, he could not simply foist such a mysterious, high-flown doctrine onto his beloved teacher, and leave the reader to suppose that is what Socrates actually believed. This must be why he makes the final, and longest, section of the Symposium a much less cerebral affair. Bringing us down to earth from metaphysical heights, the drunken Alcibiades bursts into the party and gives an elaborate speech in praise of Socrates, the man he has long loved and been loved by in return. Many of the themes raised by the previous speakers, including those in Diotima’s doctrine, are reprised in his highly personal portrait of Socrates as a man of unusual fortitude, principled desire, creative eloquence, educative vigour and true inner beauty.

Diotima recognises a place in love for both the physical and the ideal

What we learn from Alcibiades is that love as embodied by Socrates is mysterious, multifaceted and unpredictable. What matters is the unique individual who loves and is loved, not the abstractions of amatory theory. The consequences of participating in such a relationship are secondary: although it was well known to Plato’s readers that Alcibiades was to become a traitor to Athens, Plato has Alcibiades emphasise that his misconduct came about despite, not because of, his association with Socrates. It was a Greek literary convention that the last participant in any debate is the winner of the argument: the final speaker literally has the ‘last word’. Here the last word is exuberantly expressed by Alcibiades, in a speech that all but drives from our mind the high-sounding mysteries of Diotima. But does Plato mean wholly to disavow the ‘truth about love’ that he has made Socrates present in the doctrine of Diotima? Or is the central Socratic speech still the ‘truth’ that the reader is expected to acknowledge as the answer to the question ‘what is love’?

What is clear is that the popular understanding of ‘Platonic’ love derived from both these speeches – as a relationship that does not involve sex – is over-simple. Alcibiades tells how he, at the age of 20 the most handsome young man in Athens, shared a tent on campaign with the 37-year-old Socrates. He tried to seduce him physically, hugging him under the bedclothes, but Socrates was supremely uninterested in taking advantage of the physical gratification on offer, and keen only to assure the development of his young friend’s soul. But, as we have seen, Diotima recognises a place in love for both the physical and the ideal. No one can be a Socrates, a genius devoted to the quest for knowledge and spiritual enlightenment, nor can everyone be Plato, a man devoted to transcendent ideas and avid to find stability in a world of flux. So Plato cannot allow a doctrine of something as important as love to be left as something that is likely to appeal only to philosophers of his inclinations.

If the higher reaches of Diotima’s doctrine are considered barely comprehensible to Socrates, how much less will the common reader be able to embrace them? In the end, for people on earth, love is about who you love: that is why Alcibiades must have the last word. But the apparent tension between Diotima’s transcendent account of love and Alcibiades’ story of his earthly experience is best understood not as a contradiction but as complementary perspectives within Plato’s philosophical vision. Alcibiades’ speech serves not to undermine Diotima’s doctrine but to embody it, showing how even imperfect human relationships contain the seed of transcendence, while reminding us that abstract ideals must ultimately be grounded in and expressed through particular human relationships.

The ‘truth about love’ that emerges is neither purely abstract nor entirely concrete, but rather a recognition that love operates as a transformative force across multiple domains – physical, ethical and intellectual. Diotima’s ladder represents not a rejection of physical love in favour of abstract contemplation, but a developmental account of how erotic energy can be progressively refined and redirected toward increasingly comprehensive objects of desire, culminating in wisdom. Socrates’ methodological concerns and intellectual influences are shown as emerging from beyond the exclusively male Athenian coterie portrayed in the Symposium. By accepting Aspasia’s contribution to Socratic thought and method, we see how philosophical ideas might arise and develop in practice through dialogue across intellectual, gender and social boundaries. We should also recognise that Aspasia’s method of argument and ideas about love, if indeed they underlie those of Diotima, as argued, excitingly position her as a genuinely foundational figure of Western philosophy.