Listen to this essay

24 minute listen

Ernest Hemingway once declared that ‘All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn … it’s the best book we’ve had.’ One of the features that makes the 1884 novel so good is its eponymous protagonist, Huck. Raised in the antebellum South, he goes, knowingly and willingly, against the moral grain when he commits to protecting his aunt’s runaway slave, Jim. The story’s climax coincides with Huck’s crisis of conscience:

I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things [protecting Jim and turning him in], and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’ …

In believing he’s committing a sin, Huck is clearly a product of his time and place. In doing the right thing anyway, he is clearly more than that. But what is it to go against the grain and how is Huck able to do it?

Philosophers use the term ‘moral agency’ to describe our ability to make right or wrong decisions. We are agents in the sense that we are capable of responsibly choosing actions that can be morally good or morally bad. Animals and babies and people suffering from certain mental problems don’t seem to be moral agents because they’re not responsible for their actions in the same way. But this leads to hotly contested questions: where does moral agency come from? How are we able to make moral decisions? The answer to these questions lies at the heart of the nature of morality.

On a first pass, we might think of morality as being either primarily individual or primarily social in nature. The first aligns with what is referred to as the Kantian conception of morality, which emphasises rules and principles over virtues and practices; rationality and duty over desire and character. Its ultimate concern is the autonomy of the individual will. An alternative view, which cannot be linked to a single author, emphasises the communal roots of our moral concepts and values, and the role of the moral community in shaping them and our responsiveness to them. Moral agency cannot be prized apart, in this light, from the nature of morality.

Despite this dichotomy, there is wide agreement that morality and sociality are interlinked. A plausible view of moral agency will find a way to account for this linkage. On my favoured ‘ecological’ approach, the social ecology is fundamental: our moral capacities are largely, if not entirely, products of it. The challenge for ecological proponents is to explain how individuals like Huck can do things that conflict with or are absent from this ecology. This challenge is worth taking on because the alternative – prioritising the individual in the story of moral agency – fails to account for the social nature of morality and, by extension, moral agency.

We cannot be good moral agents without the critical scaffolding (praise and blame) of a moral audience

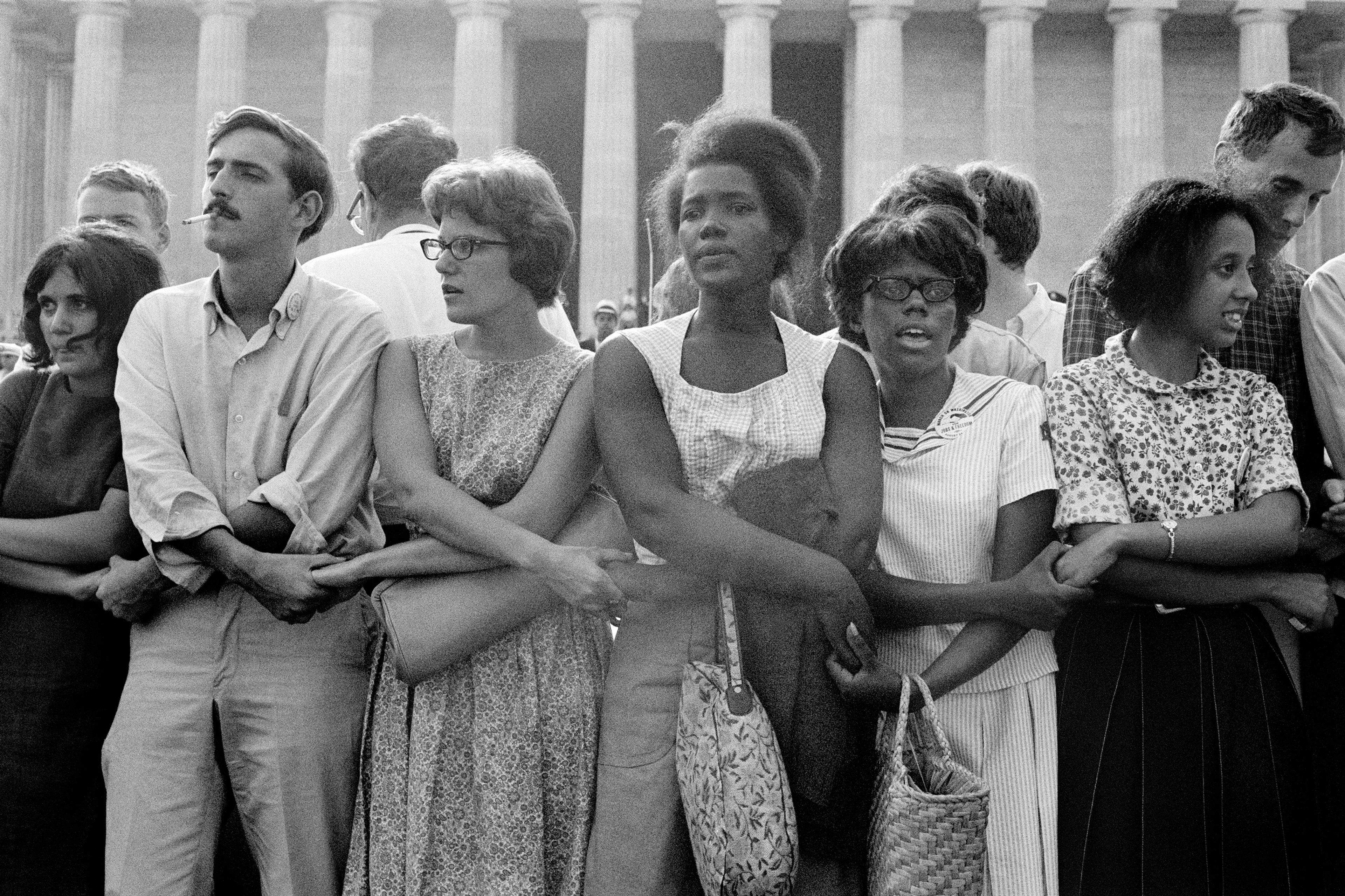

According to the philosopher Manuel Vargas, who is a proponent of the ecological approach, different forms of acculturation result in differing moral capacities. Someone who has grown up in a society that values racial equality is much more likely to be anti-racist than someone brought up in a racist society. Individual and structural oppression, Vargas argues in Building Better Beings (2013), can affect the ability of both oppressed individuals and their oppressors to discern right from wrong, and undermine their responsibility for wrongdoing. Cheshire Calhoun similarly suggests that oppressors might sometimes lack blameworthiness. This is because oppressive wrongdoing happens at the level of the social practices themselves, and social acceptance of these practices impedes an oppressor’s awareness of wrongdoing.

Vargas is especially interested in blame and praise practices because of their role in shaping our responsiveness to moral considerations. While his interest is primarily in vindicating these practices, other ecological proponents (Victoria McGeer, Philip Pettit, and Anneli Jefferson) define moral agency in terms of this role. Moral agents, they say, need only possess a sensitivity to the blame and praise of their moral audience. People are motivated to fulfil the moral expectations of those they take to be a part of this audience (their fellow moral community members). Since these expectations are communicated via praise and blame, in being appropriately sensitive to blame and praise, we stand to gain an appreciation of the relevant moral considerations. Responsible individuals care about how a potential audience might evaluate them when deciding the best course of action.

According to this ‘scaffolding’ version of the ecological view, we cannot be good moral agents without the critical scaffolding (praise and blame) of a moral audience. Scaffolding proponents give the example of a police officer, Jane, who, over the course of many years loses her sense of appropriate use of force. By imagining how an audience would react to her handling of a heated arrest, or attuning to her actual audience (and their phone cameras), Officer Jane is able to view herself critically. This prompts her to reflect on the reasons behind appropriate use of force, and her appreciation of these reasons is renewed.

This example, scaffolding proponents suggest, makes clear that our ability to act morally depends on our environment. This dependence, they say, owes first to the highly interpersonal, complex and dynamic nature of morality, and, second, to the fragility of our moral capacities. Provided that at least some moral considerations are interpersonal, whether or not morality is strictly a matter of what we owe to each other, as T M Scanlon has argued, we naturally depend on social interactions for full moral knowledge. The exhortative power of praise and blame scaffold our responsiveness to these considerations.

The complexity of the normative landscape can also be explained by ever-changing epistemic and material circumstances. When new technologies emerge, whether or not they necessitate new moral obligations, we may have to negotiate the means of fulfilling existing ones. As mobile phones became increasingly prevalent, appropriate standards of use, such as not texting while driving or when dining with a friend, had to be negotiated. This negotiation happens, McGeer suggests, through exchanges with a critical moral audience.

As to the fragility of our moral capacities, the predominant view, expressed by contemporary philosophers like John Doris and with roots going at least as far back as Plato’s ‘ring of Gyges’ in the Republic, is that we are easily affected by external pressures and psychological factors. Empirical studies show that we are more likely to do the right thing when we’ve had a bit of good luck or when we know we’re being observed. With the ring of Gyges, Plato suggests that even an ordinary person would act viciously if granted the power of invisibility and impunity. It is with this picture in mind that scaffolding proponents argue for our perpetual dependence on the scaffolding of a critical moral audience. Even the virtuous, they say, require such scaffolding to stay on the right track.

It would be easy to explain right action that conforms to an audience’s expectations as a product of this scaffolding. It would be easy to explain wrong action that goes against these expectations as the result of insufficient scaffolding (or insufficient sensitivity to it). However, this is not the case for the going-against-the-grain cases I have in mind, where individuals act for genuine moral considerations, against their audience’s false moral expectations. Insofar as our moral agency truly is a product of our ecology, how do we explain something that appears to involve acting on moral values from beyond that ecology?

Huck is sensitive to the expectation of his pro-slavery moral audience. What needs explaining is his repudiation of this expectation

There are, at first blush, three responses available to scaffolding proponents. The first is to deny that there is such a thing as going-against-the-grain; it only appears that there is. Huck goes against the grain of a moral audience, but not his true moral audience. His true moral audience, the audience to whose expectations he is in fact sensitive, is composed of abolitionists or, perhaps, just Jim. We can imagine that, during their trials and tribulations together, Jim’s moral feedback begins to matter more to Huck than the condemnation of his original moral audience. He grows to feel answerable primarily to Jim. Under this description, it is still possible to attribute Huck’s right action to the relevant ecological capacity, his sensitivity to audience. Accordingly, we could say that he goes with the grain of his true moral audience, not against it.

The problem with this response is that it would require accepting the following two mutually exclusive claims: we wholly depend on a moral audience and we have the ability to choose that audience. Such an ability would require a degree of audience-independence precluded by the first claim. Huck is sensitive to his pro-slavery moral audience – to their condemnation and its implicit expectation (to turn Jim in). Huck’s crisis of conscience reflects that sensitivity. What needs explaining is his repudiation of this expectation.

The second response (proposed by Jules Holroyd), is that going-against-the-grainers are responsive to the feedback of an ideal moral audience rather than their actual, flawed moral audience. An ideal audience is going to endorse the right values and influence behaviour accordingly. Huck’s ideal audience would, naturally, have been abolitionist. According to this response strategy, his decision to help Jim is the result of having been moved by the praise he imagined being bestowed upon him (for this good deed) by one of its members, a grandfatherly figure, perhaps.

A similar objection as to the first response can be raised against this one. As Anneli Jefferson and Katrina Sifferd point out, the ability to pick out an ideal moral audience and to recognise its expectations as the right ones requires a degree of ecology-independence precluded by the scaffolding view. Insofar as our knowledge of moral expectations is acquired via this audience, it is limited to its expectations. It also isn’t clear that imaginary, idealised feedback would hold any sway over us. Would one person’s imaginary resentment, assuming it could be conjured up, dissuade another person in the grip of intense emotion?

The third and most promising response is conciliatory. It concedes that the scaffolding view gets something wrong about the relationship between moral agency and ecology, even while seeking to preserve it in some form. Either we don’t wholly depend on our ecology or, if we do, we depend on multiple features of it, not just the moral audience. For the first, we should weaken the link between moral agency and ecology. Some moral capacities (for at least some individuals) are sufficiently robust by nature. The innate moral compass of going-against-the-grainers, we could say, is simply stronger than that of their fellows.

For the second, which maintains a strong link between moral agency and ecology, we should expand our view of moral ecology beyond the moral audience. Going-against-the-grainers have been cultivated by features in their ecology that support their responsiveness to genuine moral considerations. In Huck’s case, one such feature might be the opportunity to collaborate with Jim. In other cases, the relevant features might be the presence of certain role models, or caregiver guidance on understanding and anticipating the consequences of one’s actions on others, or conversations about moral matters, etc.

It is a version of this answer – that going-against-the-grainers are products of a complex and sufficiently fortunate moral ecology – that I find most promising. They have learned from their moral audience but, thanks to additional social scaffolding, they are able to transcend it. According to this view, moral agency is simultaneously dependent on and independent of the moral ecology. The way to make sense of this prima facie contradiction is to view our dependence as largely a developmental state and our independence as the ultimate aim.

Going-against-the-grainers have attained some degree of moral autonomy – an autonomous, direct responsiveness to the relevant moral considerations. Sensitivity to audience is crucial for responsiveness to the full range of moral considerations, but it is not sufficient. The first reason is that some genuine moral considerations are absent from or in conflict with the expectations of an actual moral audience. The second reason is that responding to audience feedback – acting to avoid blame or garner praise – does not equate (or necessarily lead) to being moved by the moral consideration.

Moral autonomy (like moral worth) is a matter of acting for moral considerations because they are genuine moral considerations (such as acting for the features that make them right), not because doing so is praise- or blameworthy. An abolitionist acts morally autonomously only when she acts out of a concern for the inherent dignity of the enslaved people she is trying to emancipate rather than because abolitionism is admirable. The morally autonomous are thus sensitive to the expectations of their moral audience, but, thanks to other features of their moral ecology, they have acquired a stronger sensitivity to the moral considerations themselves.

Blame and praise can undermine intrinsic moral motivation and moral autonomy

Just what are these other ecological features? In Huck’s case, the opportunity to collaborate with Jim appears to have been crucial, enabling Huck to see Jim as a human being, as an end in himself, with intrinsic worth and dignity. As Nomy Arpaly has suggested, Huck responds directly to these considerations despite not understanding that they are the relevant, genuine moral considerations. There is also the matter of Huck’s unique lifestyle and upbringing. He was inconsistently parented and lived outside of town. He often skipped school and church, and generally lived in a rather carefree and, in the eyes of his community, uncivilised way. Huck therefore avoided the acculturation and indoctrination to which other members of his moral community were subjected. This degree of freedom, in turn, allowed his innate moral compass – in conjunction with opportunities to exercise it – to develop properly.

Current social science suggests that we have an innate moral compass or ‘premoral disposition’. Morality starts from within, not from without. We are naturally sympathetic and cooperative. As young as aged three, children are able to distinguish social conventions from genuine moral considerations. This premoral disposition, however, must still be enlisted into a framework of values. But this process should, presumably, support and strengthen our natural tendencies rather than impose or constrict them. An earlier view of moral development, originally proposed by Jean Piaget in 1932, suggests the opposite. We enter the world as empty vessels into which moral considerations must be injected by our caregivers and educators, and then internalised. Through the internalisation process, these considerations become our own and, upon fully internalising them, we become morally autonomous.

According to contemporary research by the psychologists Richard Ryan and Edward Deci, blame and praise can undermine intrinsic moral motivation and moral autonomy. It might be, they say, that the right kinds of praise (more than blame) can support autonomy, but saying which ones and why is far from straightforward. Consider the effects of repeatedly praising a budding child pianist. She might become dependent on the extrinsic rewards of positive feedback and lose interest in performing in the absence of a supportive audience. Praising a child’s virtuous behaviour (eg, sharing toys) could have similar results. Moreover, we thereby risk externalising the child’s sense of moral authority and undermining her moral autonomy. Praise, but especially blame, can draw attention away from what really matters, namely those who are affected by our actions.

In this light, our current practices of blaming and praising children appear to conform better to Piaget’s model of moral development, according to which we are actively trying to impose morality rather than foster what is there by nature. One way to do this is to help children to anticipate and understand the ways their actions affect others, drawing their attention to their victims and beneficiaries rather than to us and our judgments. We should be especially cautious with praise and blame to avoid their undermining effects.

Most philosophers interested in blame and praise are concerned with what makes them fair or fitting rather than with their effects. They therefore tend to overlook the relationship between being responsible and holding responsible (praising and blaming). Scaffolding views are notable exceptions to this tendency. In being held responsible, scaffolding proponents argue, we become responsible. This is not just the case for children. Because scaffolding proponents view moral agency as inherently fragile and interpersonal, and the normative landscape as complex and dynamic, they regard the dependence of moral agency on being held responsible as perpetual.

The problem with the scaffolding view is that it ignores the troubled relationship between praise and blame and autonomy. We might fulfil our moral audience’s expectations strictly by way of avoiding blame or seeking praise, which makes for a shallow and unappealing picture of moral agency. Or, by way of a sensitivity to the praise and blame of a corrupt audience, we might come to embrace false moral values. By defining moral agency in terms of this sensitivity, the scaffolding view overlooks genuine moral action and thus the ability to go against the grain.

What the scaffolding view gets right is that a sensitivity to blame and praise is necessary for moral autonomy; we cannot become good moral agents on our own. However, we should reject the idea that blame and praise are sufficient (and unproblematic) for moral autonomy and that we depend perpetually on them (or on external factors more generally). By viewing the fledgling moral compass as innate – but also as in need of multifaceted social scaffolding for full realisation, at which point moral autonomy is acquired – we can explain going-against-the-grain cases from within an ecological view.

There are at least three possible objections to this approach. The first concerns luck. It may be disconcerting to some to think of moral autonomy as in any way the result of lucky circumstances. Naturally, some individuals are more sensitive to critical feedback than others. Some audiences are more critical than others. Some individuals get more caregiver guidance than others. Not everyone gets an opportunity to collaborate with people from outside their moral community. Some appear to become morally autonomous with less help than others. In short, it would seem that becoming morally autonomous isn’t really up to us.

Modern individuals will appear to go against the grain of one set of values but, in reality, go with the grain of another

This picture should inspire more than dishearten, however, prompting enquiry into the conditions of moral autonomy and encouraging efforts aimed at furnishing them. Going-against-the-grain cases are a helpful starting point for that project, as are empirical studies on moral motivation and autonomy. Importantly, if the proposed view is right, promoting moral autonomy is not going to be a matter of increasing our blame and praise practices or of inserting more moral authority more generally. It will involve supporting our innate moral tendencies in the ways described earlier and in ways yet to be identified.

A second concern is the following. Scaffolding proponents, one might think, do leave room for an innate, fledgling moral compass, and it is the difference-maker between those who just go with the flow and those who act for genuine moral considerations against the grain. However, as discussed, the moral compass involved in going-against-the-grain cases must be stronger than sensitivity to audience feedback. There isn’t room, on the scaffolding view, for this to be the case since the defining feature of moral agency is sensitivity to audience.

The third and final worry is that modern-day going-against-the-grain cases can be explained away easily. Unlike in Huck Finn’s era, the modern moral audience is value heterogeneous. This is true of Western, liberal societies, though likely many others too, especially thanks to our digital interconnectedness. Continually exposed to a vast array of contrasting views and values, modern individuals will inevitably appear to go against the grain of one segment of society or one set of values while, in reality, they’re going with the grain of another.

There are two ways to account for value heterogeneity – either in terms of multiple, contiguous moral communities or in terms of internally value-diverse moral communities. Under the first, putative going-against-the-grainers shift their membership from one community to the next, according to their newly prioritised values, and so go with the grain of their current community. Alternatively, it could be that they belong to multiple moral communities simultaneously and so, while disappointing one community’s expectations, they fulfil another’s. They are thus always going with the grain of one of their communities. Putative going-against-the-grainers within an internally value-diverse moral community are simply more responsive to fellow community members with genuine moral considerations than those with false expectations.

I’m not convinced that there is true value heterogeneity within moral communities, or that one can really choose their moral community, for reasons I explore in my paper ‘Rising above Reactive Scaffolding’ (2025). The problem for the scaffolding view runs deeper than this, though. Individuals who do the right thing do so only coincidentally. This is because they’re responding to audience feedback rather than to genuine moral considerations directly. What is more, we can point to cases where individuals respond to moral considerations that their audience has never addressed, or which are not present even within a highly diverse audience. To account for these kinds of cases, we must appeal to an independent capacity. For reasons that ecological proponents make clear, however, we must acknowledge that this capacity does not arise on its own.

The genius of Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is to be found in the union of seemingly incompatible things – the traditional and the novel, the colloquial and the eloquent, the local and the universal, the backwards and the enlightened. The genius of the character, Huck, likewise lies in the coexistence of seemingly incompatible things. Huck is both a product of his time and place, and ahead of it. He is part of a moral community, and goes against it. He is both backwards and enlightened. His moral achievement – overcoming his own, audience-imported, distorted values – is not diminished, in my view, by the fact that his moral ecology played a vital role in it. It’s rather part of the appeal. At the heart of the going-against-the-moral-grain capacity, moral autonomy, a similar juxtaposition – between the individual and the social, the innate and the ecological, independence and dependence – can be found and, I hope, appreciated.