I bought my copy of Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space at the Architectural Association’s Triangle Bookshop, at a time when inner London telephone codes still began with ‘071’ and while I was the architectural correspondent of the Sunday newspaper The Observer. That copy has been on the bookshelf above my desk ever since, kept for a lull and quieter times. Now, refreshing my memories of the book, at a moment when the prevailing blandness of planning and design rarely allows for a subjective, even poetic, response, I’ve plunged back into grappling with its enduring, infuriating attractions.

La Poétique de l’Espace (1958) was first published in English in 1964, two years after Bachelard’s death, then in paperback in 1969, and reissued in 1994. An allusive little book, its author was a highly-respected philosopher who late in his career had turned from science to poetry. Nothing about his intellectual journey had been orthodox, particularly as measured against the rigid norms of French academic life and advancement. He was from a provincial background in Champagne, a post-office employee, who rose largely through intellectual tenacity to hold a chair in philosophy at the Sorbonne. Bachelard was, by all accounts, an inimitable lecturer, and on the page he wanders around, as amiable and gentle a cicerone as you could hope to find, introducing himself as ‘an addict of felicitous reading’ whose aim is to extend perceptions, deepen resonances and reinforce connections. The Poetics of Space, his final book, soon appeared on academic reading lists, and in schools of architecture and art, squeezed in alongside the works of better-known cultural theorists and practitioners. Surprisingly enough, it is still there.

‘Bachelardian’ has become cultural shorthand for the lyrical possibilities of conjuring memory from buildings, and it is this book that brought it, and him, to prominence outside France. The first chapter, dealing with ‘the house from cellar to garret’ might well be all that the student will read, since, unlike the direct and determinist link between ideas of surveillance in Michel Foucault’s writings and their roots in Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, Bachelard’s dependence on poetry, with digressions into botany, Carl Jung and much else, is intriguing but always elliptical. It remains, according to my limited international straw poll across the generations, a book still more often cited than read.

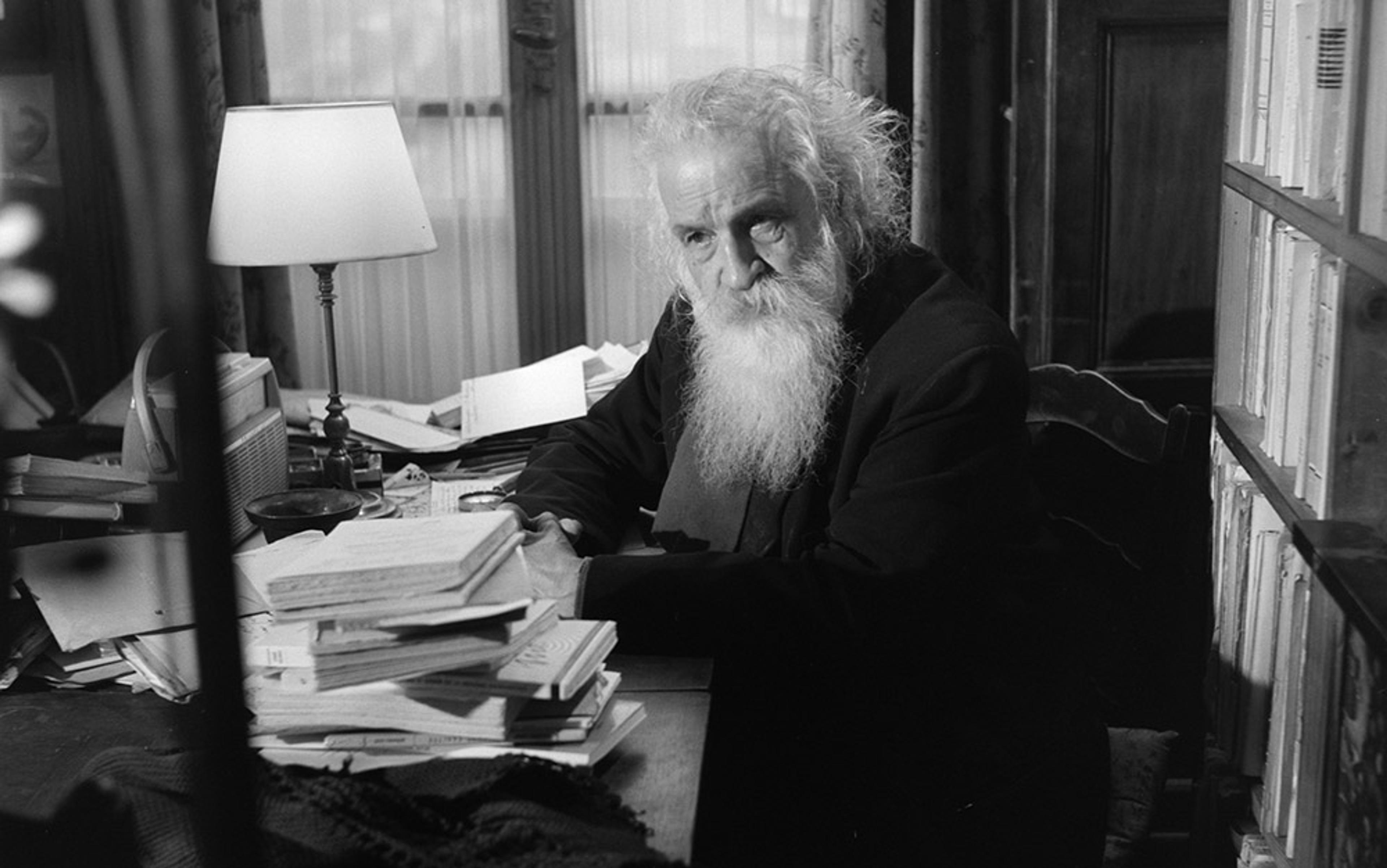

Gaston Bachelard in his study in 1961. Photo by Bernard Pascucci/INA/Getty

In 1961, Bachelard was interviewed, aged almost 80, at home in his tiny claustrophobic study in Paris. He sits snugly, seemingly shoe-horned into the only available space, between teetering heaps of books piled floor to ceiling, folios to slim pamphlets, the philosopher incarnate, down to his effulgent Socratic beard and unruly white hair. Life, he tells his awed interviewer lightly, is about thinking and then getting on with living. He admits to listening to the radio news every day.

As Foucault said of Bachelard a few years later, his characteristic approach was to avoid all defined hierarchies, any universal judgments: ‘He plays against his own culture with his own culture.’ He stood apart, separating himself from the mainstream, finding cracks, dissonances, minor phenomena that he could make his own. Poetry of every description was his raw material.

Bachelard’s previous work had advanced the theory of epistemological rupture, widely accepted by Foucault and others, in which scientific thought is freed from what had previously constrained or encumbered it. In subtle ways, left to the interpretation of the reader, Bachelard now signalled an equally clean break with the weary sterility of post-war modernism in architecture by giving weight to the unforgettable in the context of the ordinary. He considered that ‘inhabited space transcends geometric space’ but, characteristically, his words did no more than imply the considerable value of imprinted memory or the trace of meaning.

In the book, he guides us through an actual or imagined home (your choice), its comforts and mysteries, assembled and brought into focus, in a place and at a time undefined except by the limits of our own daydreams, longings and memories – those inner landscapes from which, he said, new worlds can be made. The philosopher evokes an idealised past, places the miniature against the immense, and guides us back into childhood. Once there, at home, he reminds us how we tend to look down the cellar stairs, apprehensively, while gazing upwards, towards the attic, always eager. Uncertainty is set against promise, dark against light. This house is a key to an inner self, ‘for childhood is certainly greater than reality’.

Thematically, Bachelard divided the schematic house into a vertical entity and a concentrated one, too: ‘a body of images that give mankind proof or illusions of stability’. His use of architectural phenomenology lets the mind loose to make its way, always ready for what might emerge in the process. The house is ‘the topography of our intimate being’, both the repository of memory and the lodging of the soul – in many ways simply the space in our own heads. He offered no shortcuts or routes of avoidance, since ‘the phenomenologist has to pursue every image to the very end’.

After a journey through ‘undergrounds of legendary fortified castles … a cluster of cellars for roots’, he thrusts upon his readers, in a quite shocking change of tone and imagery, a complete antithesis, in which his prejudice against urbanity and the apparent expedience of mass-produced housing is laid bare: ‘In Paris there are no houses, and the inhabitants of the big city live in superimposed boxes.’ These buildings have no ‘roots’ as he would recognise them, for there are no cellars in skyscrapers:

Elevators do away with the heroism of stair climbing so that there is no longer any virtue in living up near the sky. Home has become mere horizontality. The different rooms that compose living quarters jammed into one floor all lack one of the fundamental principles for distinguishing and classifying the values of intimacy.

Further, there is no mediating space; everything becomes mechanistic and ‘on every side, intimate living flees’.

In this astonishing and singular outburst, spine-chilling to read after the Grenfell Tower fire in London this June, Bachelard seems to be invoking an extreme vision in which individuals must fend for themselves, society having turned a blind eye to them in their dystopia. There is no other passage in the book that is as graphic, or particular. But he had been struggling, he admits, both with Paris and with insomnia, regaining his equilibrium only by returning to the poet Rainer Maria Rilke’s treasured evocation of a lamp burning in the window of a hermit’s hut, conjured up by the last (or first?) light switched on in the street as we walk home. Now the house can again assume ‘powers of protection against the forces that besiege it’ before turning into a world of its own.

The journey into intimacy is neatly evoked by drawers, cupboards, wardrobes and above all locks

An elderly man with his heart still in rural France, and a marked provincial accent to prove it, what did the increasingly unfamiliar modern city, its economics and politics, have to offer him? Warning against ‘very definitely closed utilitarianism’, he refrains from suggesting whether the anomie of the collectivist vision that he depicted was that of a capitalist or a communist society. Such was his seeming innocence, most readers do not even pose the question.

Indoors, in The Poetics of Space, the journey into intimacy is neatly evoked by drawers, cupboards, wardrobes and above all locks, although he warns, somewhat testily, against their use as gratuitous metaphors (and he is strongly averse to the idea of habit). But his pages offer continuous temptation to stray, to indulge in one’s own felicitous, serendipitous process. So in Amanda Vickery’s exploration of 18th-century domestic life for ordinary women, Behind Closed Doors (2009), she illustrates how the possessor of a simple locked container was immediately in a superior position to her peers. A single lock made her unimaginably luckier than another servant with, at most, a hiding place behind a wainscot or under a floorboard. That box or drawer, with its key, pointed to a tiny, invaluable measure of privacy, and the securing of personal space, especially in crowded, shared rooms.

The wellbeing of the warm animal (or human) protected in its nest or cocoon or cottage from the bad weather raging outside is a primitive sense of refuge that we can all share, adult or child. The appeal of a safe haven translates into domestic architecture with such features as the accommodating Arts and Crafts inglenook, seats close by the fire, Frank Lloyd Wright’s enduring penchant for an immense fireplace buried at the core of a house, or even, a favourite 1960s touch, the conversation pit – with or without its trademark shagpile carpet. The British writer Ken Worpole suggests that Bachelard’s observations apply particularly to recent developments in hospice design, in which, by focusing on the psychologically resonant imagery of the home, the hearth and the kitchen table, the familiar and the reassuring, ‘places of helpless waiting are re-fashioned … as places of contemplation and a gathering-in of memory and self-discovery’.

It is odd that a philosopher who so tenaciously excluded the harsh environments and hard circumstances of the exterior world, in mass culture, politics or architecture, was so welcomed in the modernist late-1960s while writing, essentially, about a nostalgic version of rustic Mediterranean peasant living.

Bachelard shared something of the instincts and preferences demonstrated in graphic form in the American writer and architect Bernard Rudofsky’s seminal Architecture Without Architects (1964). This book began life as an exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, supported by august figures in the contemporary architectural pantheon such as Walter Gropius, Gio Ponti and Kenzo Tange. In celebrating the seductive buildings of ‘humaneness’, Rudofsky illustrated the ‘nearly immutable’ qualities of vernacular architecture: its patterning, materials and instinctual planning, how it transmitted memory and accommodated the ‘vagaries of climate and the challenge of topography’. It was, in short, everything that modernism was not – for better and for worse.

Earlier, W H Auden had coined the word ‘topophilia’ when he was writing, surprisingly enough, an admiring introduction to an American edition of John Betjeman’s poems Slick but not Streamlined in 1947. Late in life, Auden wrote a set of 15 verses titled Thanksgiving for a Habitat (1960-1964). They were a celebration of domestic contentment in his Austrian cottage, and were structured around the rooms of the house, including ‘the Cave of Meaning’ (his study), the cellar, the attic, and his bedroom ‘the Cave of Nakedness’. In the title poem he ends, happily, writing of ‘a place I may go both in and out of’. By then, had the (French-speaking) Auden read Bachelard’s journey through a house of memories – such a topophiliac paradise?

By the time that the British architecture critic Peter Reyner Banham wrote his love letter to the south-western desert, Scenes in America Deserta (1982), it was almost inevitable that he would turn to Bachelard for elucidation since he ‘has become the most quoted authority on matters spatial in the circles in which I move’. To his disappointment, Banham found the noted thinker ‘skimpy and self-defensive’ for his purposes, since the only immensity promised, ‘a philosophical category of day-dream’, was that within oneself – altogether too fuzzy for the chronicler of New Brutalism. Perhaps Banham, his heart so recently captured by the desert, was offended by Bachelard’s offhand remark that an immense horizon of sand might be no more than a ‘schoolboy’s desert, the Sahara to be found in every school atlas’.

The ‘cupboardness’ of children’s play areas; a library tucked beneath some stairs; a universe of emotions in the corner

For all that, Banham’s fashionable world of mouldbreaking American architects, notably the postmodern Charles Moore and the theorist Christopher Alexander, author of A Pattern Language (1977), had long been in thrall to Bachelard’s book. Moore had strong ideas about the relationship of architecture to history and, beyond the private house, about the design of public space that served to enliven society. As the American critic Alexandra Lange has written, Moore had a particular penchant for leftover domestic spaces: ‘nooks, porches, lofts, and shelves designed to create room for collections and hobbies, shelter for different moods, and stages for more intimate conversations’. He referred to them as ‘saddlebags’ but they were, surely, merely assembled poetic spaces. Or maybe they sit alongside Bachelard’s admired Bernard Palissy, the 16th-century architect and landscape gardener whose investigation of fortress-building in nature included a slug that did so from its own saliva and reminded Bachelard of his early days in the natural sciences. Observing that the tiniest details ‘increases an object’s stature’ and, quoting from a dictionary of Christian botany, which exemplified the periwinkle as observed by a ‘man with a magnifying glass’, Bachelard transported his readers to a ‘sensitive point of objectivity’.

Bachelard’s earliest Anglophone readers in the fields of architecture and design had been in retreat from formulaic modernism and the backwash of deracination. Gradually the ripples spread. In Space and Learning (2008), the admired Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger gave Bachelard a charming nod when he referred to the ‘cupboardness’ of small children’s play areas: a little library tucked beneath some stairs, the inventive use of available nooks and crannies and everywhere, ‘the kangaroo as our ideal’ offering safety and sanctuary, the doorknob that is at eye level for a small child, the drawer that harbours treasures, and a universe of emotions in the corner. Following that, Colin Ward, author of The Child in the City (1978) and the most perceptive of British writers on the built environment, celebrated Bachelard’s notion of ‘experienced reality’ within childhood, a vein of rich memory available to be evoked in adulthood.

In his neat phrase ‘reading a room’, Bachelard encouraged readers to think of some place in their own past: ‘You have unlocked a door to daydreaming.’ As if in answer to that very personal quest, his description of ‘emotional shapes of the spaces inside houses and flats’ helpfully reflected Jungian ideas for the Anglo-French feminist writer Michéle Roberts as she aligned textual and spatial strands from diaries in her memoir Paper Houses (2007). Roberts configures her own journey through life as one through the city, moving from space to space, in and out of imagination. She responds to Jungian cellars, subterranean and potentially fearful places, set against attics, light and without menace, which as Bachelard confirmed ‘can always efface the fears of night’ but which are, essentially, the terrain of the German critic Walter Benjamin. Decades after the apogee of post-modernism and the lingering, often abstruse, arguments around ‘critical regionalism’, Bachelard’s book still offered ‘a nest for dreaming, a shelter for imagining’ as John Stilgoe, professor of the history of landscape at Harvard University, wrote in his introduction to the 1994 edition.

The enduring position of The Poetics of Space as a key text sees Bachelard as omnipresent. The Pritzker prize-winning Swiss architect Peter Zumthor might have been channelling him in his RIBA Royal Gold Medal address in 2013 as he spoke of architecture shorn of intrusive symbolism and imbued with experience, leading to the ultimate goal, ‘to create emotional space’. Emphasising light, materials (involving a sophisticated return to the vernacular, in the sense of the language of the locale) and atmosphere, intensified by remote and particular locations such as the house in south Devon now under construction in the Living Architecture programme, there is a clear confluence between Zumthor’s wish to be seen, above all, as an ‘architect of place’ and Bachelard’s subtle and romantic insights.

The approach can also point to an unfurling of levels of meaning and reality within an existing structure. For the architect Biba Dow, of Dow Jones in London, The Poetics of Space long ago became ‘my favourite and most essential book on architecture’. Dow and her partner Alun Jones were introduced to Bachelard’s writing by Dalibor Vesely, their first-year tutor at the University of Cambridge school of architecture. The poetic approach offered rich possibilities for extracting wider meaning, phenomenology, and the permitted exercise of the imagination. For example, the medieval church of St Mary-at-Lambeth in south London, once almost derelict, now offers a series of discrete spaces in its current life as the Garden Museum, on which Dow Jones worked in two successive phases. A chapel has become a cabinet of curiosity, displaying treasures associated with the great plant-hunter and gardener John Tradescant the Elder, founder of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, as well as of the original South Lambeth ‘Ark’ from which it grew. Beyond the outer walls, they have added a ‘cloister’ in the midst of which lies Tradescant under his exotic carved-chest tomb, a world of curiosity in itself.

But it is in the wider field of urban design that The Poetics of Space seems to me to have the greatest resonance, through the work of the American academic urbanist Kevin Lynch and others. The journey between the open vista towards the intimacy of near-enclosure was at the heart of Townscape, the campaign (or movement) waged on the pages of The Architectural Review from 1948 onwards by the British architect Gordon Cullen and the magazine’s editor, Hubert de Cronin Hastings.

It is as much the inspiration for the urban designer as it is the source of invaluable mental furniture for the small child

Less obvious was the intellectual weight of Nikolaus Pevsner celebrating, for example, ‘precinctual’ or collegiate planning in Oxford. He later thanked Hastings for encouraging his pleasurable diversion into the picturesque, allowing him, so firmly tarred with the modernist brush in the eyes of the world, ‘the saving grace of just a little bit of inconsistency’.

Cullen and his colleague Ian Nairn extended the visual analysis that Townscape suggested to a number of US cities in a contribution to Exploding Metropolis (1957) where, alongside the urbanist Jane Jacobs, they succinctly analysed, in word and image, the distinct and identifiable spatial qualities of cities from Austin to San Francisco, New York to Pittsburgh. Townscape and the contemporary exploration of ideas of ‘prospect and refuge’ – the terms, used widely in landscape theory, are those of the late British geographer Jay Appleton – share something of Bachelard’s exploration of ‘miniature’ set against ‘intimate immensity’, an unfolding sequence that is as much the inspiration for the urban designer as it is the source of invaluable mental furniture for the small child.

In The Image of the City (1960), Lynch identified the crucial role of the sense of place that ‘in itself enhances every human activity that occurs there and encourages the deposit of a memory trace’. This separation of ‘place’ in spirit and idea could, he argued, be differentiated physically and conceptually, as in edge, path, node, district and landmark. Lynch’s idea of ‘imageability’, a profound way to seek orientation, led Jacobs (a great admirer of his work) to point out in The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) that ‘only intricacy and vitality of use give, to the parts of a city, appropriate structure and shape’. By the time The Poetics of Space was available in English, an entirely compatible discourse was in train on both sides of the Atlantic, a current of thinking that could draw on Bachelard’s rich literary diet.

The distant, captured, horizon set against the closely observed and protective (or protected) has always had currency in landscape design, in past or present, occident or orient. The borrowed vista, so central to the aesthetics of oriental gardening and known as the shakkei, reflects Bachelard’s observation that distance creates miniatures on the horizon. In Recovering Landscape (1999), the US-based Englishman James Corner, one of the most persuasive of current writers on landscape and both a practitioner and an academic, cautions readers not to underestimate ‘the power of the landscape idea’ within the physical space in question, landscape being both ‘spiritual milieu and cultural image’. That particular combination of spatial sense and psychic location, Corner argues, distinguishes landscape design definitively from architecture and painting.

Bachelard’s thinking, subtly adjusted to the communal for these purposes, might argue for an intense re-examination of the fabric of the city. The historic patterning of great cities, ever more complex and many-layered versions of themselves, offers ideal templates. The High Line in New York, in which Corner played an important role from instigation to execution, is now almost completed as it approaches Hudson Yards at Penn Station. Essentially an elevated linear park, cutting north-south through the strata of the existing city – just as its 1990s predecessor in Paris does from the Bastille to Austerlitz – it reveals, reminds and confirms the part that the explorer might play in the city, while the memories linger and shreds of mystery remain.

One particularly receptive reader of The Poetics of Space is the British sculptor Rachel Whiteread, her work always transfixed by the polarities of absence and presence. The detail of the domestic setting evoked in Untitled (Paperbacks) (1997) is a masterly exploration of negative space but, above all, it culminates in her piece House (1993), now long gone: the concrete cast of an entire terraced house in (then) unfashionable Bow, given a short (artistic) stay of execution before its demolition, conveyed multiple meanings.

As the British scholar Joe Moran writes, viewed from a distance it might have looked like avant-garde sculpture but ‘closer inspection revealed pockmarks and imperfections in the minimalist façade, signs of the daily life of the house: soot-blackened fireplaces, exposed joist ends slightly rotten from damp, the indentations left by light switches, old plug sockets and door latches’. In that extraordinary installation, so literal, Whiteread had translated something of Bachelard onto the actual streets of east London, and from there, through its brief, but widely recorded and archived existence, passed House into memory.