Consider this story of corporate contrition. From 1932 to 1968, the Japanese chemical manufacturer Chisso Corporation discharged mercury into Minamata Bay on the west coast of Japan, causing a lethal and disfiguring condition known as ‘Minamata Disease’. Chisso’s own scientists knew that they were to blame, yet the company refused to stop dumping mercury and instead claimed that explosives from the Second World War had contaminated the water. As a gesture, the company offered nominal ‘sympathy’ payments to victims.

In the pro-business and anti-environmentalist climate of the 1960s, Chisso could wave away evidence of the connection between its pollution and the increasingly widespread sickness. But activists in the devastated fishing community persisted in their campaign, and the political winds began to shift. In 1968, one of the company’s own doctors confessed on his deathbed that he had found convincing evidence that their pollutants caused the disease, but that he had destroyed the evidence on Chisso’s orders.

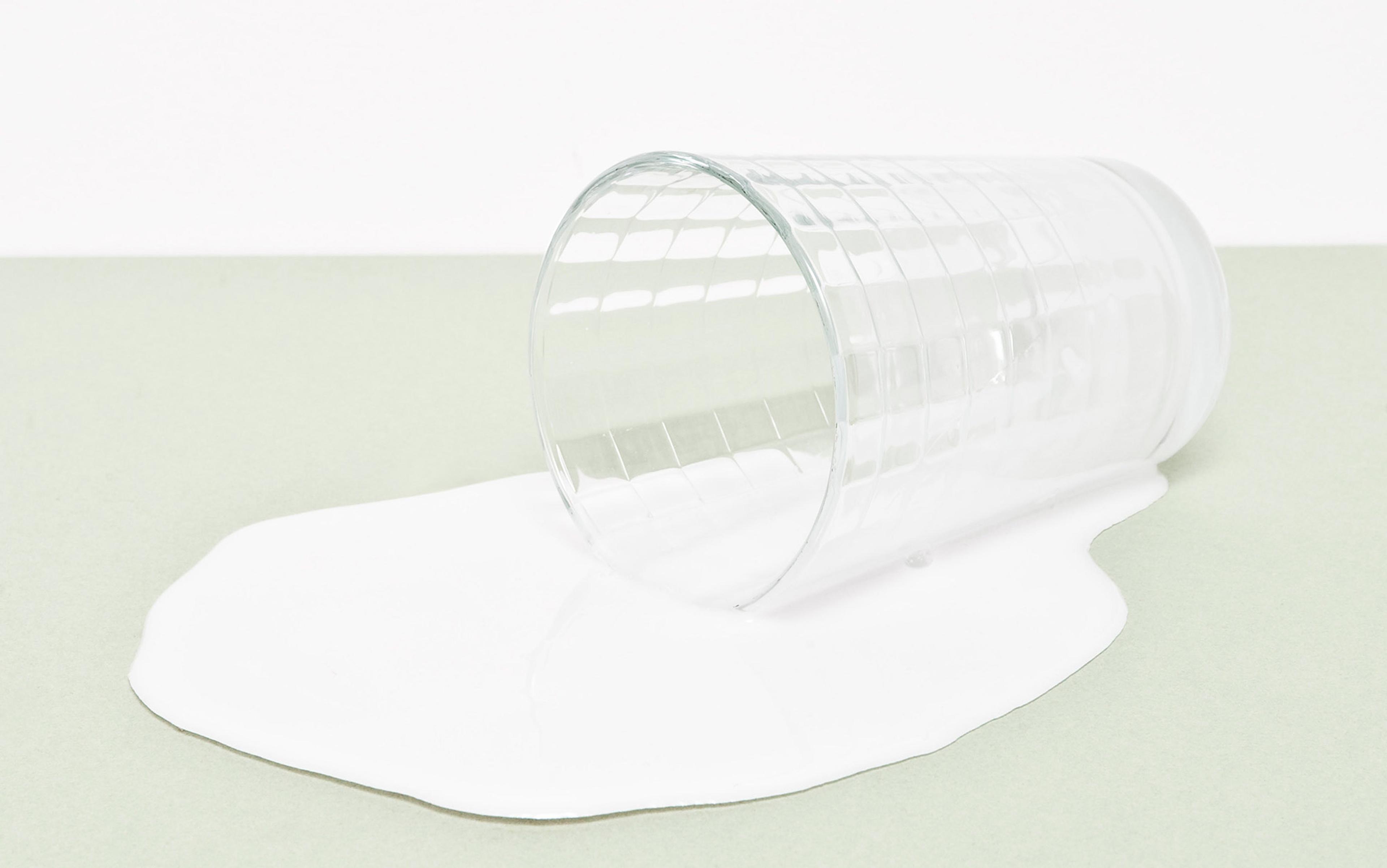

It was a turning point. Victims – who had been ostracised from their community, banned from stores and restaurants, and treated like outcasts – finally got a meeting with chief executives. When the company’s president, Kenichi Shimada, claimed that Chisso could not afford the damages, one victim stood up and proclaimed: ‘If I don’t get the indemnity money, I can’t live.’ To prove the point, he shattered a glass ashtray on the negotiating table and slit his wrists.

Shimada quickly conceded.

Victims insisted on an apology. A real one: Shimada had to prostrate himself before victims and accept blame for injuries to thousands. Japanese courts sentenced two Chisso executives to prison terms. Extensive reforms followed. Payments to victims were so generous that the Japanese government had to start bailing out Chisso in 1978 in order to ensure that it could maintain its ‘burden of shame’. In 1973 the Japanese government, which had earlier been complicit in the cover-up, officially recognised 3,000 Chisso victims. Chisso itself stopped dumping. It paid for the majority of the multibillion-dollar remediation. And it paid the fishermen whose livelihood it had destroyed to catch poisoned fish and deliver them to its toxic incinerators for disposal.

You couldn’t exactly call this a happy ending. Yet the apology accomplished multiple important objectives. It helped to redress a horrible situation. It was meaningful. And for that very reason, it probably wouldn’t happen in the US today.

Apologies interact with the law in strange ways. Let’s start with criminal law. The modern penitentiary originated in the 18th century as a place of penance: it was where society sent its outcasts to study their Bibles, experience quiet self-alienation, hear the word of Christ, and repent. Less has changed than you might think.

Between 90 and 95 per cent of all criminal convictions in the US result from guilty pleas rather than jury trials. In many if not all of the millions of cases in the US criminal justice system, courts determine punishments in part based on their sense of whether the offender is remorseful or not. We might wince at the idea of secular states engaging in the ‘soul crafting’ of the original penitentiaries, but we still expect state agents to divine the essence of the offender’s nature and offer a suitable punishment based on her badness. We are, in other words, still in the grip of old spiritual traditions. And that leaves us with an old problem.

Findings of remorse in criminal contexts typically occur in the star chambers of intuition. State officials consult their gut feelings, evaluate a few emotional cues and then render a (typically unappealable) decision about the offender’s character. On the whole, they do not explain why they find an offender’s remorse compelling. They do not disclose or defend their standards of contrition. The US Federal Sentencing Guidelines attempted to add some consistency to punishments by allowing reductions in sentences for those who ‘accept responsibility’, but, in practice, accepting responsibility has come to mean agreeing to a plea even while denying guilt. The US Supreme Court has ruled that remorse can determine whether an offender lives or dies, yet we entrust such determinations to ‘know it when I see it’ standards, as if judges and juries can look into the eyes of offenders, intuit the depths of their evil, and punish accordingly.

This discretionary latitude has predictable consequences. Regardless of their blameworthiness, rich offenders tend to get more credit for their remorse than poor ones, a generalisation that holds throughout the US criminal process. Police officers are more likely to let a warning suffice when the offender is rich. Parole boards are more likely to find that a rich inmate is sufficiently reformed. By contrast, the apologies of minorities, the poor and the mentally disabled often fail to convince.

Several studies suggest that judges discount apologies from racial minorities, for example, because they find them lacking in credibility. Clothes, speech patterns, posture, class signifiers and so on all create what social scientists call a ‘demeanour gap’ between races and classes. If a person looks and acts in a way that the court associates with criminals, that person must overcome powerful implicit biases before a judge credits her repentance. Similar concerns arise for mentally ill offenders, who make up about half of all of those incarcerated, and whose conditions might well impair their ability to adopt a suitably contrite demeanour.

Elite attorneys and $1,000-per-hour ‘apology consultants’ can coach defendants on how to use their remorse, such as it is, to maximal strategic benefit

Are these biases necessarily the result of discriminatory intentions? They needn’t be. One suggestive study found that the facial shape of corporate executives has a peculiar influence on public relations crises: it seems that ‘baby-faced’ spokespeople evoke better responses during minor crises and ‘mature faces’ produce better results in major ones. Along the same lines, it is easy to imagine how the faces of criminal offenders might influence perceptions of their remorse, leading state agents to exercise in-group bias in favour of those whose high-status lives look most like their own. By allowing officials to render impressionistic judgments on something as elusive as remorse, we open the door to discriminatory effects.

That said, the benefits of money are not always so subtle. As long as we distribute legal representation according to wealth, those with the most resources will be able to hire the best advisers. Elite attorneys and $1,000-per-hour ‘apology consultants’ can coach defendants on how to use their remorse, such as it is, to maximal strategic benefit: how to express it, when to manifest it, when to avoid it. Rich offenders can throw money at the problem in other ways: enrolling in state-of-the-art treatment programmes, or providing victims with considerable redress. The repentant poor, meanwhile, languish in jail, unable to make bail, receive treatment or provide much for their victims.

What can be done? If we are to continue reducing punishments for apologetic offenders (and for the record, I think we should), it seems clear that we must be much more explicit about how we classify the meanings of remorse. We should specify how those meanings should affect punishment, and how these standards apply fairly and transparently in all cases. We could promulgate definite standards, train state agents to apply the standards consistently, and vigilantly watch for discriminatory applications. The state could, with enough resources and political will, mitigate these problems in criminal law.

But judges are not the only ones vulnerable to a well-aimed apology, and courts are not the only place where the wealthy can use their advantages to deflect the full force of the law. Apologies have become very big business in civil litigation, and it isn’t at all obvious what procedures could be put in place to guard against their abuse. Judges can be trained to refine their craft and do a better job of evaluating remorse. What can we do when those sitting in judgment are just ordinary people – desperate and vulnerable civil litigants, injured by powerful organisations?

One would not expect to find many apologies in civil law unless contrition – rather counterintuitively – conferred a strategic advantage. And so it does. This tactical use of remorse results in part from an apology’s ability to appear as something more than tactical. One of the primary sources of an apology’s economic value, in other words, lies in its tenuous identity as something that transcends money.

Consider Donna Bailey from Texas. An outdoor education instructor and mother of two, in 2000 she had been studying to become a physical education teacher when a rollover crash left her paralysed below the neck. The vehicle she was riding in was a Ford Explorer equipped with Bridgestone/Firestone tyres. That particular combination of vehicle and tyre resulted in an estimated 250 fatalities and as many as 3,000 additional serious injuries. Bailey sued for $100 million. She also asked for an apology.

She wants something like an apology. What she gets instead is a confidential settlement, an ambiguous expression of sympathy, and a sum of money minus legal fees

Three Ford attorneys visited Bailey at her hospital bed and apologised on Ford’s behalf. The apology was captured on video, but with the sound turned off. We don’t know why the lawyers sought to limit access to their words, nor what they said to Bailey. But their gestures seemed to satisfy her: the same day, she settled for an undisclosed amount. Ford’s spokesperson issued a statement: ‘We are pleased to have resolved this case with Donna Bailey and we extend our sympathies to her and her family.’ Bailey also commented: ‘The gist of the whole thing was that they were truly sorry… I felt like it was very sincere.’

Was it, though? Ford and Firestone had been entwined since 1896. Henry Ford actually fitted the Model T with Firestone tires. But the Explorer accidents ended that relationship. Ford publicly blamed Firestone, Firestone blamed Ford. It therefore seems unlikely that Ford’s attorneys accepted blame when they spoke to Bailey. It also seems improbable that this semi-private apology explained how and why Ford had done something wrong, which specific individuals deserved blame, or what they would do to prevent it from happening again.

Why, then, did Bailey buy it? According to her attorneys, she did ‘not want her case to stand merely for someone who wanted a monetary award’; rather, she ‘wanted to advance public safety and protect lives’. But it’s hard to see how her decision could have advanced that goal, if Ford never acknowledged any fault.

This turns out to be a common story. A victim suffers harm. She wants something like an apology: she wants to know what happened, she wants someone to admit wrongdoing, she doesn’t want to stand by while someone ‘gets away with’ violating a moral principle that she cares about, she wants to be respected and recognised as wronged, she wants the wrongdoer to feel badly, she wants to know this isn’t going to happen again to her or to anyone else, and she wants the wrongdoer to take practical responsibility for redressing her injury. What she gets instead is a confidential settlement, a rather ambiguous expression of sympathy, and a sum of money minus legal fees. This happens again and again. And it saves companies an astounding amount of money.

According to the general counsel of Toro – a US company manufacturing lawn-maintenance equipment, and an early leader in corporate apologies – the old ‘litigate everything’ policy produced a pattern over hundreds of claims. Toro would spend between $60,000 and $70,000 on legal fees, and settle just before trial for about $15,000. Then someone had an idea. The company would send a ‘good listener’ to the injured person’s home along with a team of investigators to document the injury and details regarding the person’s financial situation. The representative would then offer sympathy and a settlement offer without admitting guilt, cloaking the exchange behind a mandatory confidentiality agreement.

This strategy saved Toro approximately $45,000 per claim, $900,000 in annual settlement costs, and $1.8 million in annual liability insurance premiums. In all, Toro estimates saving more than $75 million between 1991 and 1999.

Stories such as Toro’s explain why the corporate world has taken apologies to heart. That interest has in turn led to further innovations, including a rather bold and well-funded campaign to define apologies as something other than a confession of responsibility. Contrary to my arguments in I Was Wrong (2008) and without any serious consideration of the moral features and cultural histories of repentance, attorneys and legal scholars now commonly insist that an apology is specifically not synonymous with an admission of guilt.

This has some disconcerting effects. Once divorced from blame, apologies emerge as a tactical defence. Attorneys can deploy them as what they describes as an ‘attitudinal structuring tactic’ in order to ‘lubricate settlement discussions’. Southwest Airlines in the US employs a full-time ‘apology officer’ who sends out roughly 20,000 letters – which all include his direct phone number – to dissatisfied customers per year. At best, apologies are now a standard customer satisfaction tool: ‘We’re sorry for the inconvenience,’ but frankly we’re not admitting blame nor will we change. At worst, they become wolves in sheep’s clothing, preying on a deep-rooted spiritual desire to reconcile.

The situation becomes considerably more troubling once legislators get involved. Some states now prevent expressions of sympathy from being admitted into evidence, but do not exclude statements of fault. Others protect apologies that can be characterised as ‘general benevolence’. Some even protect admissions of wrongdoing, fault, errors or mistakes. Still other statutes provide general protection for apologies while leaving the term ambiguous. And these trends have gained traction internationally. The ombudsman for New South Wales in Australia declared that an apology – defined as loosely as you could imagine – ‘does not constitute an express or implied admission of fault or liability by the person in connection with that matter, and is not relevant to the determination of fault or liability’.

in practice the laws provide another way to protect wrongdoers from liability

There’s no mystery about what’s driving these counterintuitive laws. In the view of the business community, costs for liability insurance have become excessive. From this perspective, injured parties – and ‘frivolous’ plaintiffs seeking to fleece corporations – receive so many large awards that liability threatens business. And so, business lobbyists argue, we find ourselves in a ‘litigation crisis’: we must reform tort laws to reduce costs for businesses. Reforms include initiatives such as capping non-economic damages, reducing punitive damage awards, and requiring losing parties in civil litigation to pay the winner’s attorney’s fees. For these reasons, lobbyists push to have ‘safe apology legislation’ bundled into larger tort reform packages.

Their path is smoothed considerably by the way in which safe apology legislation appeals to social conservatives. The very mention of apology conjures both ‘personal responsibility’ and spiritual traditions of repentance – even when the law defines apologies as something other than an admission of fault. Like many tensions in the allegiance between social and economic conservatism, the spiritual values and economic interests of apologies in law co‑exist on the same platform even as they seem at cross purposes. Lobbyists and legislators can cite reduced litigation costs when speaking to the corporations who fund them, but then proselytise to their religious base about how apology laws enable parties to ‘reach out to others in a humane way without fear’, even as they know that in practice the laws provide another way to protect wrongdoers from liability.

In principle, perhaps apology safe havens could allow parties to reach some degree of moral reconciliation. Commentators often trace the origins of ‘safe apology’ laws to Massachusetts in the 1970s, where early advocates sought a protected legal space for conversations like the one a state senator had wanted to have with the truck driver who’d killed his daughter. In practice, however, the informality usually allows the powerful to gain further advantages and co-opt the process, just as they have done with other alternative dispute mechanisms such as binding arbitration. In the end, confusing, ambiguous and inadmissible apologies serve to advance business interests. Perhaps that explains why Texas legislators tried to un-define apologies within a tort reform package. Informality and imprecision, like discretion, favour the powerful.

How much does this matter? Well, consider the social function that civil law is meant to serve. For consumer rights advocates, large tort awards help to ensure that products are safe. The risks of potential litigation are supposed to outweigh the promise of potential profits: this, after all, is the mechanism that is meant to remove dangerous products, such as asbestos insulation, from the market. If companies can fob us off with a few contrite-sounding words, what incentive do they have to fix their products?

if I never have to accept personal blame, and liability insurance covers the costs of apologetic redress, what lesson have I learnt?

Something deeper is at stake, too. If the core meaning of an apology resides in the apologiser rendering herself vulnerable – I admit that I was wrong, I deserve blame, I must change, and I owe you redress – legal safe havens undermine the basic attitudes and consequences of contrition. Contrary to those who argue that legal protections will somehow encourage contrition, a willingness to accept fair consequences is, in my view, part of the very meaning of repentance. This vulnerability accounts for the fact that apologies can convey such gravitas in the first place. By contrast, with safe apology legislation, ‘I am sorry’ goes the way of ‘not guilty’: it becomes just another move in the game. It leaches meaning from our long-standing, widely shared moral traditions.

If the law codifies conceptions of apologies, it should provide clear and defensible definitions. As corporate crisis management experts advise, ‘complexity is the apologist’s friend’. Rather than blinkering everyone – confusing the meanings of apologies, adding layers of distortion and then burying the whole thing in confidential settlement agreements – we should be specific about what apologies do and do not mean in particular conflicts, and parse their value accordingly.

Remember the Chisso story. We should hold that in mind when we review the conduct of an institution such as BP, which not only offered obviously vacuous apologies for the disaster of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010 but also enjoyed a $10 billion tax benefit by writing off clean-up expenses. Insurers likely covered the bulk of the remaining costs. Which leaves us with the central question about apologies and public well-being: if I grow richer from harming you, if I never have to accept personal blame, and if liability insurance covers the costs associated with apologetic redress, what lesson have I – and my fellow executives – learnt? As with criminal law, apologies in civil law can provide a powerful opportunity for reconciliation and social justice. Or they can distort our deepest spiritual traditions to compound the advantages of the privileged.