‘Most people are other people,’ wrote Oscar Wilde. ‘Their thoughts are some one else’s opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.’ This was obviously meant as a criticism, but what exactly is the criticism? Most people are other people, in a different sense to how Wilde meant it: the vast majority of people are not me. The enormous size of this majority – billions to one – guarantees that there will be somebody better than me at anything I can think of. If I make a dress for the first time, I am wise to follow a pattern. If I cook a meal for the first time, I am wise to follow a recipe. This is (as far as I know) my first time living as a human being, so why wouldn’t it be wise for me to emulate a successful model of living, especially when there are so many candidate models, past and present?

When Wilde was writing, literary culture had reached the pinnacle of Romantic individualism. In that culture, it was obvious what’s wrong with being other people: doing so is a betrayal of your true self. Each of us was thought to possess a unique, individual identity, sewn into the very fabric of our being. Walt Whitman celebrated ‘the thought of Identity – yours for you, whoever you are, as mine for me,’ and defined it as: ‘The quality of BEING, in the object’s self, according to its own central idea and purpose, and of growing therefrom and thereto – not criticism by other standards, and adjustment thereto.’

In the 20th century, the assumption would be famously challenged, for example by Jean-Paul Sartre, who proclaimed that humans come into existence with no definite identity – no inborn ‘central idea and purpose’ at all: ‘man is nothing else but that which he makes of himself’. This is a logically tricky point, since it’s unclear how something devoid of all identity could ‘make itself’ into anything. We can’t suppose, for example, that it makes itself according to its whims, or inclinations, or desires, since if it has any of those then it already has an identity of some sort. This gets us into a quandary. Simone de Beauvoir – Sartre’s partner in philosophy, life, and crime – responded to it by admitting that self-creation can work ‘only on a basis revealed by other men’.

But popular culture has by and large responded by retreating uncritically to the old Romanticism. Apple’s Steve Jobs advised a graduating class at Stanford not to ‘let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice’ and to ‘have the courage to follow your heart and intuition’, which ‘somehow already know what you truly want to become’. Advertisements for shampoo and travel money apps advise you to dig deep inside and find the True You. The question of how we each came to be pre-programmed with this unique true identity, this articulate inner voice, is left aside, as is the more troubling question of how the advertisers can be so confident in betting that your true self is going to love their products.

How would things look, philosophically, if we cleared this Romantic notion out of the picture? I think we can get a sense of it by looking at the great philosophical tradition that flourished before the formation of the Qin dynasty in what is now China. The most well-known philosopher from this tradition is Confucius (Kong Qiu, 孔丘), classically believed to have lived from 551 to 479 BCE. In reality, books ascribed to him were probably written by multiple authors over a long period. The most famous of these, the Analects, propounds an ethical ideal based on emulating admirable examples. The philosopher Amy Olberding wrote a whole book devoted to this topic, Moral Exemplars in the Analects (2012). For Confucius, being ‘other people’ is precisely what you should be aiming at – as long as you emulate praiseworthy people like the great sage-kings Yao and Shun or indeed Confucius himself. The objection that this would betray your true inborn identity doesn’t come up. The idea that we each have an individual, inborn, true identity doesn’t seem to appear in this tradition.

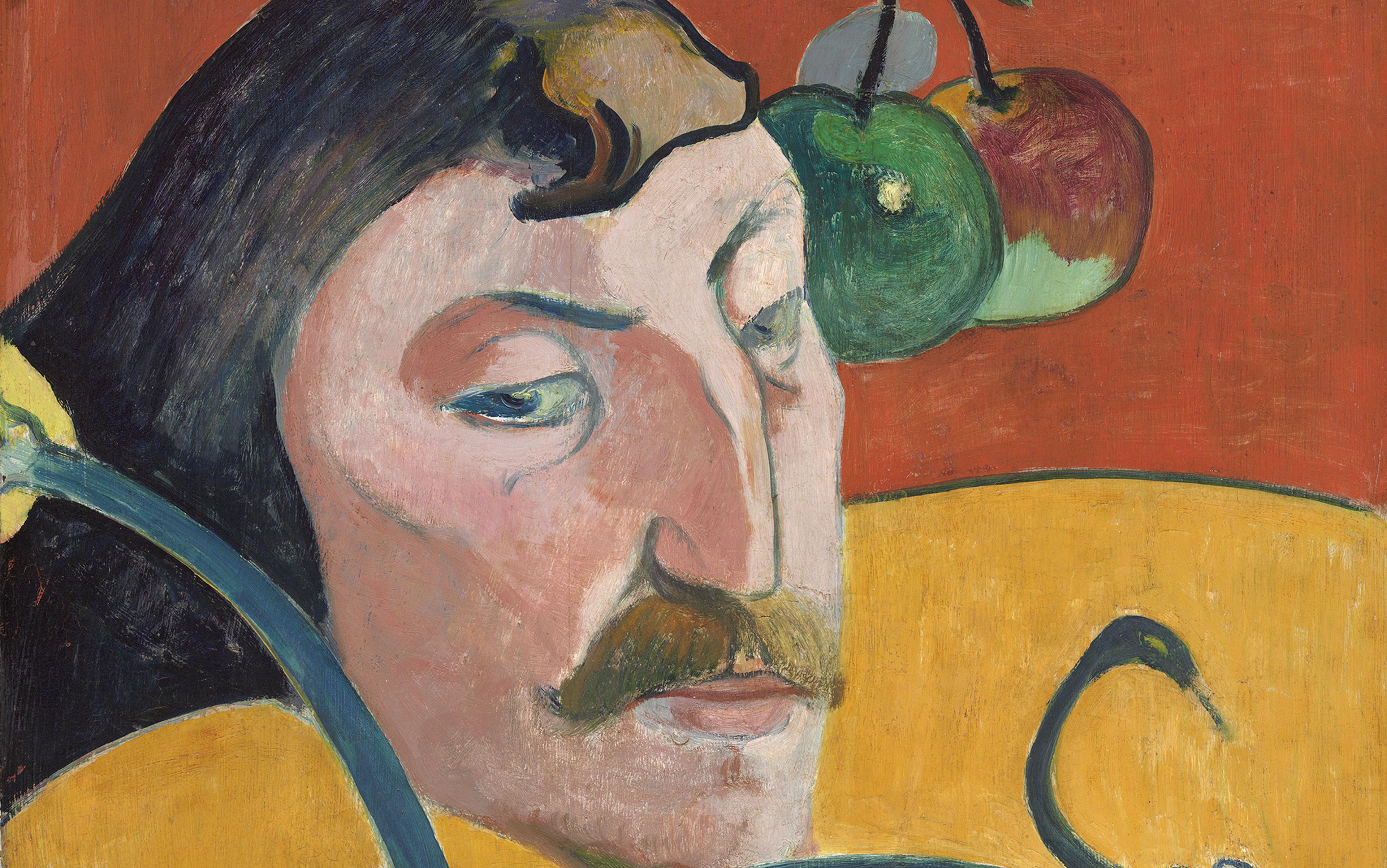

Detail from a handscroll painting illustrating the ‘Nushi zhen’ (‘Admonitions of the Instructress of the Ladies in the Palace’), a text composed by Zhang Hua c232-300 CE. Courtesy the British Museum, London

What the tradition does recognise is role-identities. Confucius was concerned that these were being lost in his time. In the Analects, he declares that his first act in government would be to ‘rectify names’ (zheng ming, 正名). This is a complex concept, but some light is shed on its meaning by another passage, in which he is asked about zheng (政) – social order – and replies: ‘Let the lord be a true lord, the ministers true ministers, the fathers true fathers, and the sons true sons.’ Confucius feared the loss of the traditional zheng, which he associated with the recently collapsed Western Zhou Kingdom, leading to a social chaos in which lords, ministers, fathers, and sons no longer played their appropriate roles. ‘Rectifying names’ could mean ensuring that people live up to their names – not their individual names but the names of their social role or station (ming, 名, can be used to mean ‘name’ but also to denote rank, or status). To the question ‘Who am I?’, Confucius would like you to reply with your traditionally defined social role. As to how you should play that role, the ideal would be to emulate a well-known exemplary figure who played a similar role. Under the Han dynasty, which adopted Confucianism as a sort of official philosophy, many catalogues of role-models were produced, for instance Liu Xiang’s Traditions of Exemplary Women (Lie nu chuan, 列女傳), full of models of wifehood, motherhood, ladyhood, etc.

The ethical ideal is not to replace a conformist identity with an individual one. It is to get rid of identity altogether

Confucius’s philosophy was opposed in his era, but not by Romantic individualists. On one side was Mozi (or Mo Di, 墨翟), who proposed that we should take nature as a model rather than past heroes. For this to make sense, nature had to be anthropomorphised into having cares and concerns – a comparison could be made with the ancient Greek and Roman Stoics.

Courtesy the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art

On the other side was Zhuangzi (Zhuang Zhou, 莊周), perhaps the strangest philosopher of any culture, and a central focus of my book, Against Identity: The Wisdom of Escaping the Self (2025). Zhuangzi (again, the writings ascribed to him – called the Zhuangzi – were probably written by multiple authors) rejected Confucian role-conformism. He argued that you shouldn’t aim to be a sage-king, or an exemplary mother, or any other predetermined role-identity. You shouldn’t aim, in Wilde’s terms, to be other people. In our highly individualistic culture, we can’t help but expect this line of thinking to continue: just be yourself! But this is not what Zhuangzi says. Instead, he says: ‘zhi ren wu ji (至人無己),’ translated as: ‘the Consummate Person has no fixed identity’ or ‘the ultimate person has no self’. The ethical ideal is not to replace a conformist identity with an individual one. It is to get rid of identity altogether. As the philosopher Brook Ziporyn puts it, ‘it is just as dangerous to try to be like yourself as to try to be like anyone else’.

Why is it dangerous? In the first place, attachment to a fixed identity closes you off from taking on new forms. This in turn makes it difficult for you to adapt to new situations. In her book Freedom’s Frailty (2024), Christine Abigail L Tan puts it this way: ‘if one commits to an identity that is fixed, then that is already problematic as one does not self-transform or self-generate.’ Borrowing a term from psychology, we could call this the problem of ‘identity foreclosure’. The American Psychological Association defines ‘identity foreclosure’ as:

premature commitment to an identity: the unquestioning acceptance by individuals (usually adolescents) of the role, values, and goals that others (eg, parents, close friends, teachers, athletic coaches) have chosen for them.

But the radical message of the Zhuangzi is that it can be just as dangerous a ‘foreclosure’ to accept the role, values and goals that you have chosen for yourself. Doing so cuts you off from the possibility of radically rethinking all of these under external influences.

Indeed, it drives you to resist external influences, for a simple reason. We have a strong survival instinct – an urge to continue existing. But continuing to exist means retaining the form that makes you yourself and not something else. Turning into a corpse, obviously, doesn’t count as surviving, but neither would turning into something too radically different from what you fundamentally are. I fear waking up tomorrow with my body, memories and personality replaced by those of somebody else about as much as dying in my sleep; indeed, it might well count as me dying. Surviving means remaining the same in crucial, definitive respects. But this means that the more narrowly you define yourself, the more defensive you will feel against external influences that might change you.

The term ‘identity’ lends itself naturally to this sense of self-definition. It comes from the Latin identitas, with the root idem, which means ‘same’. A common expression is unus et idem, ‘one and the same’. Your identity is whatever must stay the same in order for you to remain you. A narrow identity makes heavy demands of consistency, upon you and also upon the wider world. If your identity is bound up in being a harness-maker, then your survival (under that identity) requires not only that you keep working at making harnesses; the harness industry must also stay viable. If the industry dies out, for example with the coming of automobiles, then you will find yourself in a desperate identity crisis, panicked at the idea that nothing you can now be will count as what you had hitherto recognised as yourself. Hopefully you will find new things by which to define yourself. But you could have saved yourself the anguish by not binding up your identity with something so specific in the first place.

Now suppose that your identity is bound up with certain religious or political beliefs. In that case, your survival instinct will be put on alert anytime anything threatens those beliefs. The more convincing an argument against them seems, the less able you will be to hear it. The more appealing an alternative seems, the harder you will push it away – for fear of changing and losing yourself in the change. In this way, foreclosing on a fixed identity, even one that you have chosen, will push you to insulate yourself from external influences. We can think of an example from Sartre: ‘the attentive pupil who wants to be attentive exhausts himself – his gaze riveted on his teacher, all ears – in playing the attentive pupil, to the point where he can no longer listen to anything.’

But the world is always changing, in ways that we cannot predict. When attachment to a fixed identity drives us to close ourselves off from external influences, those influences might otherwise have been very valuable in guiding us through change and uncertainty. There are many stories of Australian colonists rejecting the Indigenous knowledge that could have helped them survive in a harsh and unknown environment, due to their excessive attachment to an idea of themselves as scientifically and racially superior. This idea was incompatible with the suggestion that they might have something to learn from those they saw as ‘naked savages’.

When we seek a definite identity, we betray our true nature as fundamentally fluid and indeterminate

There is another reason that trying to be yourself, in the sense of some fixed identity, is dangerous. To appreciate it, we must ask: where did you get the idea of that fixed identity? Remember that we are now imagining ourselves in a cultural context devoid of the Romantic notion that each of us is born with an inborn self. The compiler of the earliest surviving text of the Zhuangzi, Guo Xiang (252-312 CE), also provided a commentary, which outlines a very different notion of self.

Guo’s commentary draws out elements in the Zhuangzi that criticise the Confucian ethic of model-emulation, which Guo calls following ‘footprints’ (ji, 跡). For example, Guo comments on one passage as follows:

Benevolence and righteousness naturally belong to one’s innate character [qing, 情], but beginning with the Three Dynasties, people have perversely joined in such noisy contention over them, abandoning what is in their innate characters to chase after the footprints of them elsewhere, behaving as if they would never catch up, and this too, has it not, resulted in much grief!

The reference to ‘innate character’ here might mislead us into reading this passage in a Romantic way – a familiar celebration of being your true, inborn self rather than following in the footsteps of others. But when Guo uses terms like this, or ‘original nature’ (benxing, 本性), he appears to mean something quite different. Tan explains: ‘original nature (benxing, 本性) does not actually mean that it is unchanging and fixed, or that it is inborn, for it simply means unfettered.’

Zhuangzi’s view, as interpreted by Guo, is that when we seek a definite identity, we betray our true nature as fundamentally fluid and indeterminate. We end up pursuing some external model of definiteness. Even if the model is one of our own devising, it is external to our true indefinite nature. One story in the Zhuangzi tells of a welcoming and benevolent but faceless emperor, Hundun. Hundun has a face drilled into him by two other emperors who already have faces of their own. As a result, he dies. The story suggests that fixed identity always comes to us from the outside, from others who have already attached themselves to fixed identities and drive us to do the same, not usually by drills but rather by example. This peer-driven attachment to identity kills our fundamental nature, which is formless and fluid like Hundun (his name, 混沌, means something like ‘mixed-up chaos’, and each character contains the water radical signalling fluidity). Our true Hundun-nature is the capacity to take on many forms without being finally defined by any of them.

This encounter with a distant philosophical culture liberates us to ask questions we might not have otherwise thought to ask. Imagine if we hadn’t been conditioned to believe that our true self is something fixed and inborn. Would we have inevitably found our way to this idea? Or might we instead, like Zhuangzi, have supposed our true nature to reside in boundless suppleness and fluidity, upon which any definite identity can only be a foreign imposition? What would our culture look like if that was the dominant idea we all had of our true self? Would it reduce human life to a meaningless chaos of wandering without purpose? Or could it, perhaps, be more peaceful, more adaptable, and more exciting?

I am inclined towards the latter position. Admitting my confirmation bias, I see examples everywhere of how identity holds us back. In a complex and unpredictable world, nations need more than ever to learn from each other. Instead they are closing their doors to foreigners and going into international dialogues with megaphone on and earplugs in. In modern democracies, people vote for who they are, not what they want, as Kwame Anthony Appiah puts it, leading to policies that pit identity groups against each other, rather than pursuing collective benefits – or indeed even real benefits to any one group. Information technology puts the whole world at our fingertips, yet people remain shockingly incurious about anything that goes outside their own narrow cultural sphere – as if fearful that exposure to too much difference will detach them from their treasured identity. And even when current patterns are shown to be unsustainable, we find it difficult to change them, due to our identities becoming somehow bound up in them.

He doesn’t know if he is Zhuangzi, who dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly now dreaming of being Zhuangzi

A personal example of the latter is my experience of grief. As I slowly lost my father to Alzheimer’s disease, I realised that the terrifying part of grief is the feeling of not only losing a loved one but losing yourself. I struggled to imagine myself without a figure who shone out warmth in my earliest memories. I was stuck in a desperate, hopeless compulsion to yank back the past into the present. It was my father’s own courage in the face of his much more direct loss of identity that taught me that I too could adapt, learning to accept and even appreciate the complete transformation of myself.

The most famous story of the Zhuangzi is the Butterfly Dream. Zhuangzi awakens from a dream, in which he was a butterfly fluttering freely. He doesn’t know if he is Zhuangzi, who dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly now dreaming of being Zhuangzi. This story puts Zhuangzi in contact with ‘the transformation of things’ – a reality in which identities are always fluid and never fixed. As Kuang-Ming Wu points out in The Butterfly as Companion (1990), the butterfly’s ‘essence is fluttering’. Hundun and the butterfly are symbols of an inner fluttering – an inner indefiniteness that lies deeper in us than any fixed identity, whether chosen or imposed.

The demand to be true to ourselves – as individuals, as communities, as churches, parties, cities, nations – leads us to manhandle the world. Keeping ourselves the same means keeping things in the right shape to provide the context for our self-definition. Others are trying to keep things in the right shape to suit their self-definitions. The result is a world full of strife and devoid of progress. Perhaps it is time to seek our inner fluttering instead.