‘Six years have passed since I discovered that my son was using drugs,’ wrote Vincenzina Urzia in Anthony and Me (2014), a memoir of her son’s drug addiction. ‘I was really sad all the time and devastated, not to mention how worried I was about his wellbeing. My son was not the same person anymore.’

This is a puzzling idea, for someone to become ‘not the same person any more’. The phrase smacks of philosophy – perhaps even obscurity. Yet it is simultaneously apt, capturing the emotive sense of no longer recognising someone whom we once knew. Many have witnessed someone they loved change so profoundly that the person remaining seems an entirely different one.

Drug dependence powerfully exemplifies this phenomenon of not being the same person: a mother sees addiction transform her son into a shadow of his former self. Other examples can evoke the same feeling. A ruinous relationship or divorce leaves a friend so changed that he seems like a totally different person. So too can Alzheimer’s disease – which affects up to half of elderly Americans. A parent or relative develops severe Alzheimer’s, and it seems as if the person once known has disappeared. Across a range of experiences, profound changes can make well-known friends or family become entirely different people.

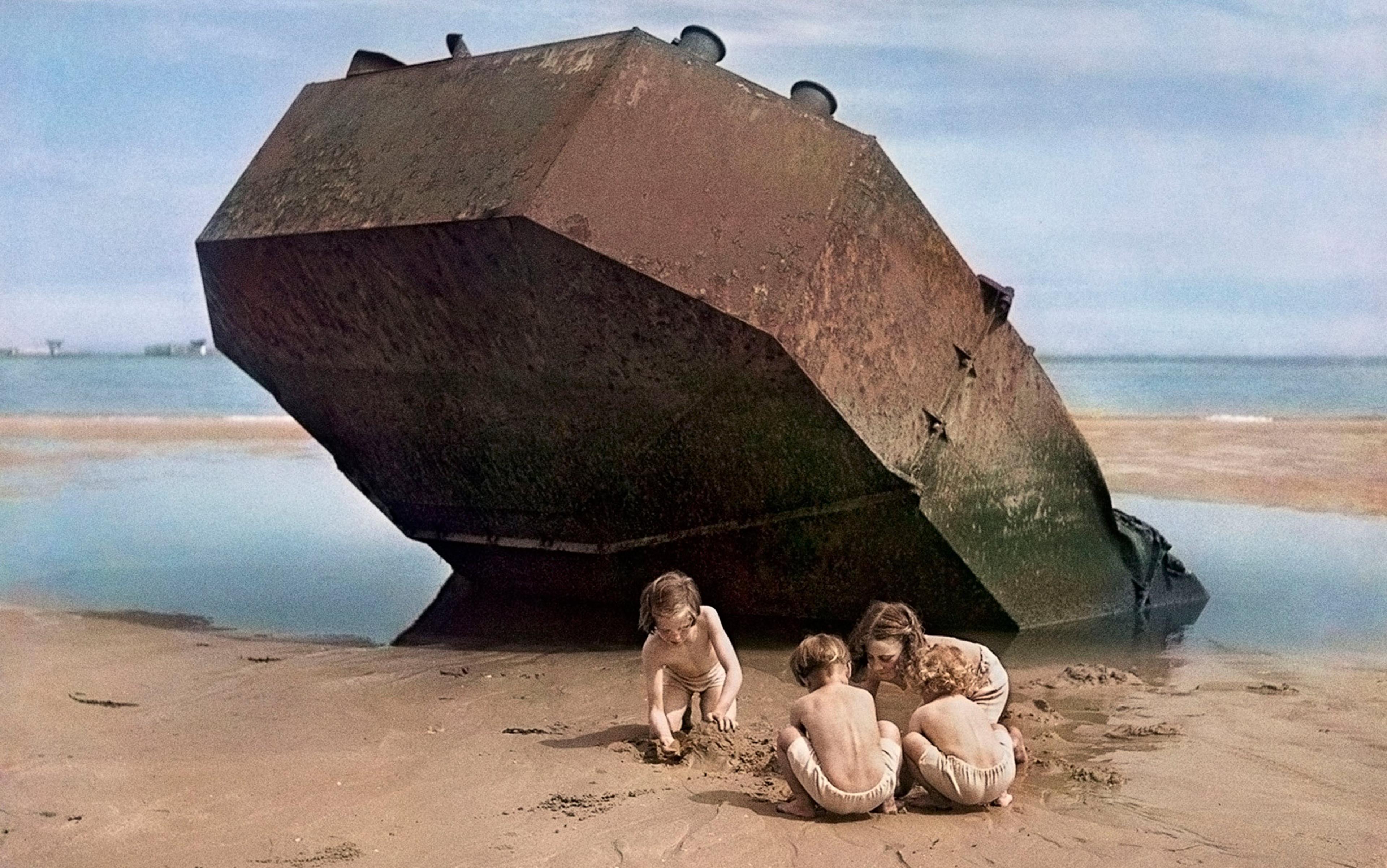

These examples suggest that change fundamentally challenges our sense of self. Yet, many other large changes don’t disrupt our identities. In fact, some profound changes actually seem to make us become really or truly ourselves. Consider finding one’s true self through romantic love; discovering a hidden life passion; committing to radically improving one’s health; or experiencing a religious or spiritual conversion. The same effect might arise from harder experiences, such as surviving a period of wartime or incarceration. All of these result in tremendous transformations, but they don’t threaten identity. Instead, these changes seem to unearth our core selves, making us become who we really are. This allows for a seemingly paradoxical statement: paradigm cases of continuing to be the same person involve becoming radically different.

This idea – that change is essential to the self – becomes clear through a philosophical thought experiment. Think about yourself as a newborn. Fifteen years after your birth, your friends and family saw a person who was strikingly dissimilar from the newborn. That teenager had a bigger body, sharper mind, deeper values and richer social life. In many of the most important ways, that teenager was nothing at all like the newborn. But the two were undoubtedly the same individual. It’s not true that for you and the newborn to be the same person, we expect for you to be exactly identical; in fact, for you to be the same person, there are actually many ways in which you should be radically different from your newborn self.

Philosophy often emphasises the significance of being the same person despite change. It asks how various changes – such as total memory loss or a brain transplant – might create a different person. This helps to clarify aspects of personal identity and the self, but it also overshadows intuitions about the significance of change itself. The ideal or model way to persist through time is not to stay exactly the same. Instead, it is to change.

The significance of change is not limited to the way we speak or theorise about personal identity. Underlying various practical concerns are presumptions about a changing self, rather than a static one. For example, a custodial trust for a young child is premised on the assumption that the beneficiary will be very different from the present child. The trust is intended for the individual that is the same person as the young child, but it is not intended for someone with the linguistic, mental and moral capacities of a young child. Many long-term commitments share this character; they are predicated on expected change or development, not exact similarity.

Philosophers have noted cases in which change triggers practical concerns. For example, it might seem that certain personal changes warrant breaking a promise – one seemingly made to a different person. But in the case of a custodial trust, we seem more concerned about the appropriateness of granting the trust if the adult person is exactly similar to the child, than in the case when the adult is developed (and therefore, different). The implicit conditions underlying these judgments are not simply ones of static similarity, but of assumed change over time.

What are the changes that foster these kinds of ideal or model transformations? These essential changes are not arbitrary. In our thought experiment, the appropriate changes were ones that indicated a newborn’s purposeful development. That thought experiment exemplifies stark change consistent with personal identity, and which also appears fundamental to the self. We certainly wouldn’t encourage a teenager to strive for exact similarity to a newborn, in fear of losing her true identity. Part of what it means for a teenager to really be the same person as the newborn is to be substantially transformed in a purposeful way: learning language, sociality and morality.

Purposeful self-modification does not problematise personal identity. Instead, it reveals facets of one’s true self

Ordinary life offers numerous examples of identity-preserving and purposeful changes. Sometimes, tremendous change suggests features of a person’s essence or deep self. Committing to a relationship, flourishing in a new career or mastering a novel hobby inevitably changes us, but it does so in ways comporting with self-narrative. These changes do not make us seem ‘less ourselves’. Instead, these changes seem to help us become who we are.

The history of philosophy evokes purposeful change as central to the self. The ancient Greek philosopher Plotinus invoked the image of self-sculpture. He encourages us to ‘cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one radiance of beauty. Never cease “working at the statue” until there shines out upon you from it the divine sheen of virtue.’ Purposeful self-modification does not problematise personal identity. Instead, it reveals facets of one’s true self.

Centuries earlier, the Chinese philosopher Mencius described people as cultivators of seeds of virtue. If we grow into good persons, it seems that we have grown in just the right way, cultivating our seeds of virtue. Importantly, we are born like seeds – not full-grown trees – of virtue. We are not born perfectly good and developed, persisting by maintaining that exact goodness. Instead, we are born with mere seeds of virtue that flower through development.

Similar ideas recur throughout the history of philosophy. In Ecce Homo (1908), Friedrich Nietzsche describes the phenomenon of becoming what you are: ‘Becoming what you are presupposes that you do not have the slightest idea what you are … the organising, governing “idea” keeps growing deep inside … before giving any clue as to the domineering task, the “goal”, the “purpose”, the “meaning”.’ And in the interview ‘On the Genealogy of Ethics’ (1983), Michel Foucault remarks that: ‘We have to create ourselves as a work of art.’ This essay merely takes inspiration from these passages, and interpretative debates remain about each. The core insight is that, in contrast to a view that identity is really about static persistence or similarity, the self is organic and dynamic. Being the same person over time is not about trying to hold on to every aspect of our current selves; instead, it is about changing purposefully.

A common thread among these historical views is the vision of something deep inside, be it the core of a statue, the seed of virtue, or the governing idea of ‘becoming what you are’. These conjure an important intuition about purposeful development. If all proceeds correctly, the future self will not be exactly the same as the present self. Instead, the future self should be a purposefully developed – thus different – version of the present self. And often, the future self will represent a blossomed or flourishing version of the earlier self, where the earlier self contained small seeds or hints of the future.

Understanding this kind of change requires a broader reflection on purpose. What does it mean to develop purposefully? Human purposes are complex, so first consider the purpose of something simpler. Take an acorn. The purpose of an acorn is to develop into an oak tree. We might attribute this purpose to a particular acorn in various ways. For example, because we know that acorns typically grow into oak trees, one specific acorn might appear to have that purpose. But we also attribute purposes retrospectively. Upon seeing an unknown object grow into an oak tree, we might reflect back and attribute growing into an oak as one purpose of that object. Moreover, upon learning that a particular acorn grew into a very tall oak, we might reflect back and think that growing very tall was a more specific purpose of that earlier acorn.

One’s purpose is often hidden. Often we do not have the slightest idea what we are – until we become it

A person’s apparent purposes are broader, including developing language and values, becoming a social and moral being. But there are some similarities to the acorn. We learn many of the apparent purposes of persons through theory. People typically develop language and morality, and it seems that newborns also have that purpose – even when newborns themselves do not manifest any linguistic or moral behaviours. The same reasoning might apply to more individualistic purposes. Perhaps upon learning that a particular child grew into a great athlete, we might even reflect back and think that such a specific purpose was discernible even in the younger child – even one who had not yet displayed such features. Core aspects of a person’s identity often appear traceable to seeds in their youth.

This dynamic and purposeful view of the self is at odds with the focus of some personal-identity discussions. Those debates focus on persistence despite change, taking for granted that persistence involves similarity of something. In a broad sense, this purposeful view involves similarity – similarity of purpose across a life – but, as Nietzsche notes, one’s purpose is often hidden. Often we do not have the slightest idea what we are – until we become it.

This concern about not knowing what we are, or what we will become, motivates recent philosophical questions about ‘transformative experiences’. These are experiences that transform a person in deep and unpredictable ways: having a child, serving in the military, embarking on a new career, being incarcerated, or falling in love. Decisions to embark on such experiences problematise decision theory. How can we evaluate what we don’t know? Of course, we can evaluate some uncertain decisions. Although I’ve never gone on a tequila and Twinkies diet, I conclude that it’s probably a bad call. But other unknown decisions are harder to evaluate, since the person that I would become in virtue of the decision is – in some fundamental way – different from my current self. For instance, having a child might result in such a profound personal change that it is difficult to even assess the decision. A list of pros and cons from my current perspective does not seem to adequately represent the decision, since the ‘me’ that results from having a child is so radically different from my current self.

The intuitions about the significance of personal change provide a possible response to these problems. The key is our beliefs about purpose. Recall how we think that an acorn should develop into an oak. Similarly, we intuit that a newborn person should develop, growing bigger, wiser, becoming moral and social. Learning language is as transformative an experience as any, but we don’t doubt that it is one that preserves identity and enriches one’s self, rather than one that frustrates identity or deteriorates one’s true self. Radical changes such as learning language seem to develop us into the people we are really meant to be – even though the person we become is strikingly different.

Yet, humans differ in important ways from plants and other animals. Our apparent purposes are broader than those given by nature or even culture. While the singular purpose of an acorn is to grow into an oak, humans are creatures of multifaceted and diverse potentiality. This implies an exciting – but dangerous – aspect of the purposeful self. Often, who we seem to be now becomes more lucid over time. To illuminate this feature, consider examples of great achievements. Imagine that a young child grows into a great artist. In such a case, we reflect back to years earlier and see the seeds of artistry in the younger person. This judgment might be an error or bias; maybe it is not truly their purpose. But it is undoubtedly a common story we tell.

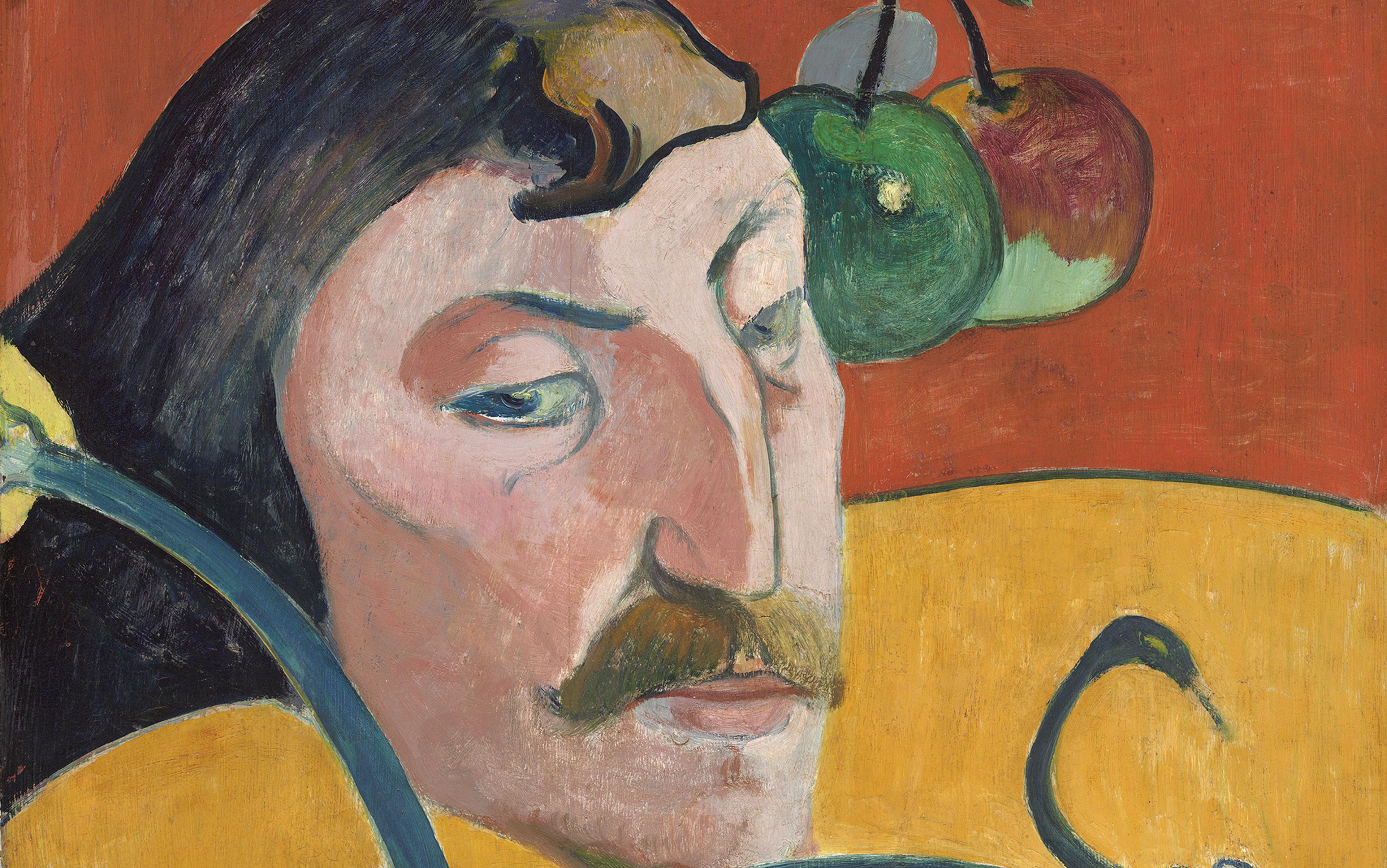

And whether this story is right or wrong, it seeps into our morality. The philosopher Bernard Williams introduced a fictional thought experiment about ‘Paul Gauguin’ inspired by the life of the real artist. In the thought experiment, young Gauguin decides to leave his family to pursue his artistic ambitions. As Williams astutely noted, whether young Gauguin’s choice is blameworthy or praiseworthy seems to depend on how things turn out. Philosophers call this phenomenon ‘moral luck’. If old Gauguin fails as an artist, young Gauguin seems blameworthy, but if old Gauguin succeeds, we say, as Williams puts it in Moral Luck (1981): ‘a little grudgingly perhaps: “Well, all right then – well done.”’ A different way to understand the story is in terms of young Gauguin’s apparent true self and purposes. Upon seeing old Gauguin the successful artist, we attribute seeds of artistic potential in young Gauguin; pursuing his true calling seems more excusable. In the hypothetical world in which old Gauguin fails, we worry that the young man who left his family – years earlier – departed from his moral and familial purposes (as we now perceive that he did not really have an artistic one).

An acorn that transforms into an apple is no longer the same thing, as is a person who transforms into a god

This interpretation of the self as purpose-driven also makes sense of a recent experimental-philosophy discovery: we have a tendency to see improvements as more identity-preserving than deteriorations. People judge changes for the better as more consistent with identity than changes for the worse. The hypothesis of the purposeful interpretation is that the change for the better informs our impression of the earlier person. When we see someone improve, we attribute this goodness to the potentiality of their earlier self. Upon seeing the growth of a magnificent oak, we are more confident about what the acorn was really meant to be. And upon seeing a person’s positive powerful improvement, we are more confident about that part of the person’s true self, at the time before the improvement. However, upon seeing a person’s deterioration, we worry that they have departed from their true callings.

Understanding the self as purpose-driven also explains the limit to this thinking: not all improvements seem identity-preserving. We don’t perceive just any improvement as part of self-flourishing. As Aristotle noted and Martha Nussbaum elaborates, we would not wish our friends to become gods, for we would lose them. Extreme and unusual change – even change for the better – might make someone seem like a different person. An acorn that magically transforms into an apple is no longer the same thing, as a person who magically transforms into a god is no longer the same thing. A person can persist through tremendous transformations into a language user, a moral and social being, an artist or athlete, but not into a god.

Although this idea of purposeful persistence supplies an answer to some philosophical puzzles, we might object to its unwaveringly naturalistic advice. Becoming linguistic and social creatures are advisable transformative experiences, but what about having children? It is not obvious that by forgoing this apparent naturalistic purpose we fail to become truly ourselves. What about a deaf person’s cochlear implant – is the choice to not implant truly a departure from one’s true self? Talk of human ‘purpose’ deleteriously overshadows different ways of being. The changes that the majority thinks are typical or ‘natural’ purposeful changes are not necessarily the changes consistent with every individual’s true self.

Our intuitions about people’s purposes raise deep and problematic questions. What makes us perceive purposes and what are the purposes of various persons? Moreover, all the discussion thus far is about apparent purposes. But are these ‘purposes’ real or illusory? If they’re real, are they actually relevant to personal identity or the true self? Or perhaps we remain fully ourselves even if we do not achieve these purposes?

This leaves us in a complicated place. Our conceptions of identity and the self are enmeshed in a web of beliefs about purpose. To be sure, understanding the self as dynamic and purposeful provides clarity and insight. In contrast to the static view of identity, we should endorse some developmental model and criteria of identity, at least ones acknowledging our moral and social development. Not all changes are threatening to our identity, and we should embrace the significance of purposeful change to our selves. But we should also be cautious of unreflective teleological reasoning.

Despite these questions about the limits of purpose’s relevance to identity and the self, for now these reflections provide a modern moral. As personal identity puzzles emphasise the significance of persisting despite change – for example, by maintaining the same body or mind – we should also recall the vital role of change itself. Every worldly example of continued personal identity involves tremendous transformations – whether it is developing language, sociality or morals; discovering a hidden passion; coming out of our closets; changing careers; falling in or out of love; growing or finding a family. Such dynamism does not throw our identities into question; instead, these changes represent some of the most significant aspects of our selves.