What does it take to be the same person over time? This question has vexed philosophers for millennia. If an individual’s character changes enough, can this disrupt identity to such an extent that it no longer makes sense to say that we are dealing with the same person? That seems a reasonable conclusion to draw when the change is extreme. But I wanted to explore whether there might be more going on than this, and specifically whether the direction of change, not just the magnitude of change, might be a key factor.

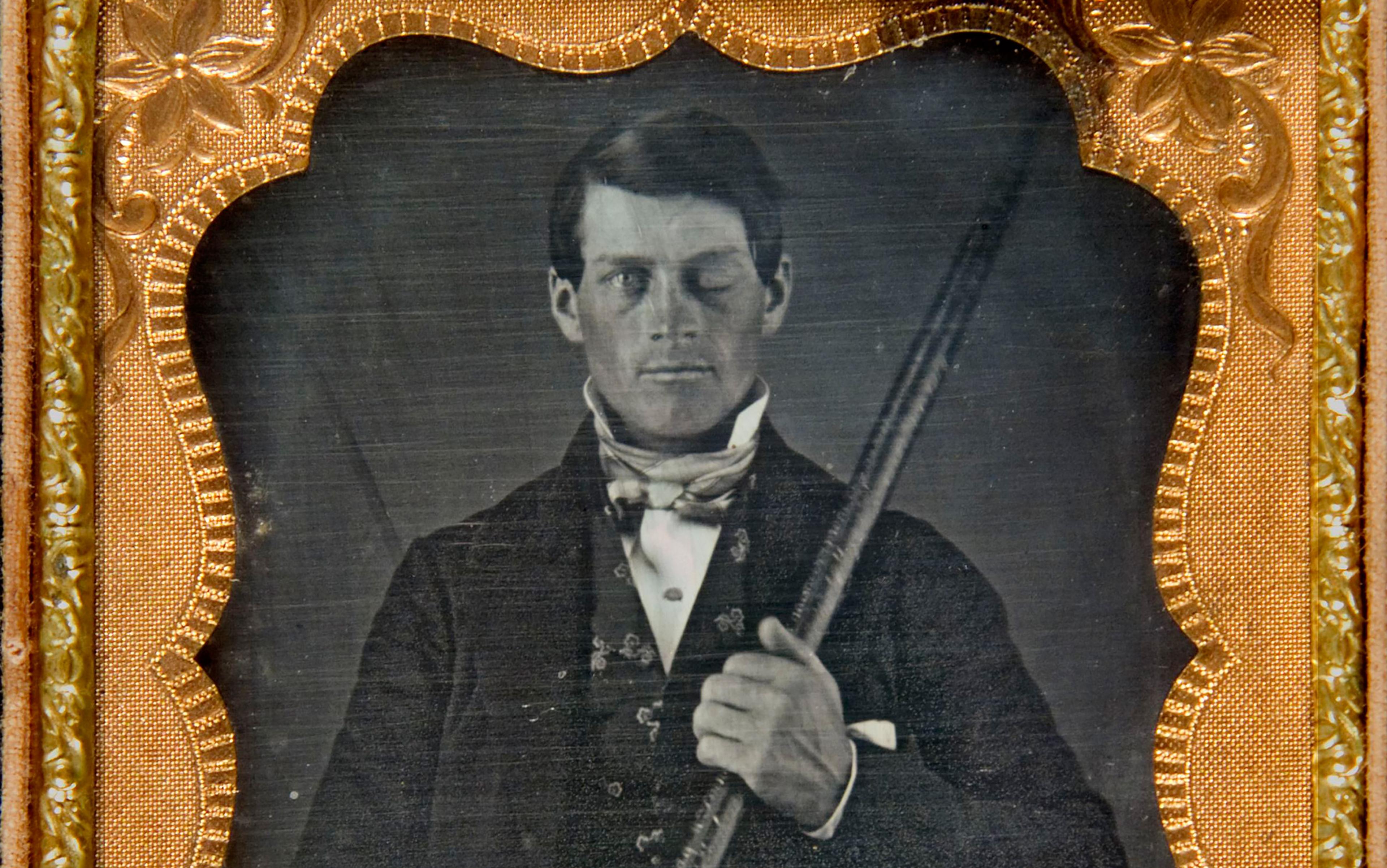

In order to explore this question, I presented participants (Aeon readers who responded to a survey) with one of two different scenarios. The two scenarios expressed different versions of a classic thought experiment. They were based on the well-known story of Phineas Gage: a 19th-century railroad worker who had an unfortunate accident in which a tamping rod went right through his skull; he survived, but underwent a major character transformation as a result of brain damage – or so the story goes. Consider a vignette based on the myth of Gage:

Phineas is extremely kind; he really enjoys helping people. He is also employed as a railroad worker. One day at work, a railroad explosion causes a large iron spike to fly out and into his head, and he is immediately taken for emergency surgery. The doctors manage to remove the iron spike and their patient is fortunate to survive. However, in some ways this man after the accident is remarkably different from Phineas before the accident. Phineas before the accident was extremely kind and enjoyed helping people, but the man after the accident is now extremely cruel; he even enjoys harming people.

Gage’s friends and family were inclined to regard the man after the accident as ‘no longer Gage’. This case study is often taken to show that some substantial changes of character can disrupt personal identity to the extent that it seems reasonable to say that this is a different person in an important sense. However, in this case, the accident involved not just a large change, but specifically a deterioration: the man after the accident is seen as worse than Gage before the accident. The typical interpretation of this case is that sufficient magnitude of character transformation disrupts identity. But might this other feature, the direction of change (‘improvement’ or ‘deterioration’) be partly responsible for judgments about identity?

To test this hypothesis, consider a replication of an X-phi (experimental philosophy) study. Aeon readers were invited to read either the ‘Deterioration Case’ (the vignette printed above, based on the real Gage) or the following ‘Improvement Case,’ in which a similarly sized change results in an improvement (differences in bold):

Phineas is extremely cruel; he really enjoys harming people. He is also employed as a railroad worker. One day at work, a railroad explosion causes a large iron spike to fly out and into his head, and he is immediately taken for emergency surgery. The doctors manage to remove the iron spike and their patient is fortunate to survive. However, in some ways this man after the accident is remarkably different from Phineas before the accident. Phineas before the accident was extremely cruel and enjoyed harming people, but the man after the accident is now extremely kind; he even enjoys helping people.

All participants rated whether they thought the (improved or deteriorated) man after the accident was still Gage. They rated this on a scale from 1 (still the same person) to 7 (not the same person); those who read the deterioration scenario rated on average 3.48, while those who read the improvement scenario rated on average 2.68. Those who read and rated the ‘Improvement Case’ were more inclined to see the man after the accident as still Gage than those who read the scenario based on the classic ‘Deterioration Case’. This suggests that large changes do not always affect perceived personal identity in the same way: intuitions about personal identity can depend on the direction of change.

The same improvement/deterioration effect sheds light on another philosophical thought experiment: Derek Parfit’s Russian Nobleman case. This is Parfit’s original thought experiment (a ‘Deterioration Case’), from his book Reasons and Persons (1984):

In several years, a young Russian will inherit vast estates. Because he has socialist ideals, he intends, now, to give the land to the peasants. But he knows that in time his ideals may fade. To guard against this possibility, he does two things. He first signs a legal document, which will automatically give away the land, and which can be revoked only with his wife’s consent. He then says to his wife: ‘Promise me that, if I ever change my mind, and ask you to revoke this document, you will not consent’. He adds: ‘I regard my ideals as essential to me. If I lose these ideals, I want you to think that I cease to exist. I want you to regard your husband then, not as me, the man who asks you for this promise, but only as his corrupted later self. Promise me that you would not do what he asks.’

Parfit suggests that some might think of the older Russian as a different person from the younger Russian, noting that:

if this man’s wife made this promise, and he did in middle age ask her to revoke the document, she might plausibly regard herself as not released from her commitment. It might seem to her as if she has obligations to two different people. She might believe that to do what her husband now asks would be a betrayal of the young man whom she loved and married. And she might regard what her husband now says as unable to acquit her of disloyalty to this young man.

Parfit does not himself claim that the young and the old Russian are different persons, but this Russian Nobleman case is a seminal thought experiment suggesting that major dissimilarities can seem to disrupt personal identity. However, this judgment might also gain its force from a Phineas Gage effect, as the change described might be seen as not only a big change, but specifically a deterioration.

Another experiment tests the part played by direction of change in this scenario. Participants read either the original Russian Nobleman Case above (a ‘Deterioration Case’), or a slightly revised ‘Improvement Case’ (differences in bold):

In several years, a young Russian will inherit vast estates. Because he has anti-socialist ideals, he intends, now, to not give the land to the peasants. But he knows that in time his ideals may fade. To guard against this possibility, he does two things. He first signs a legal document, which will automatically not give away the land, and which can be revoked only with his wife’s consent. He then says to his wife: ‘Promise me that, if I ever change my mind, and ask you to revoke this document, you will not consent.’ He adds: ‘I regard my ideals as essential to me. If I lose these ideals, I want you to think that I cease to exist. I want you to regard your husband then, not as me, the man who asks you for this promise, but only as his corrupted later self. Promise me that you would not do what he asks.’

Participants reading the Deterioration [Improvement] case were told about some changes that occur many years later:

Imagine this young man’s wife made this promise so the land would [not] go to the peasants. But years later, her husband, now the old Russian, asks her to revoke the document, so as to [not] give the land to the peasants.

Compared with participants responding to Parfit’s original (Deterioration) case, those responding to the revised (Improvement) case agreed more strongly that the old Russian was the same person as the young Russian, free to release his wife from her promise.

Positive-Kirk and Negative-Kirk are both dissimilar from the original, yet Positive-Kirk is the captain and Negative-Kirk is the impostor

Further evidence that direction of change affects identity can be seen in popular examples. Take, for example, ‘The Enemy Within’ (1968), an episode of the original Star Trek television series. A transporter malfunction splits the ship’s Captain Kirk into two people, one with the properties of his negative side, the other with the properties of his positive side. Positive-Kirk and Negative-Kirk are both dissimilar from the original captain, yet the ship’s crew refers to Positive-Kirk as Captain Kirk and Negative-Kirk as the impostor. Improved Positive-Kirk is taken as identical and deteriorated Negative-Kirk as non-identical to the original.

Another example is found in the sci-fi novel Flowers for Algernon (1966) by Daniel Keyes. Charlie Gordon begins the story as mentally disabled. He enters surgery and, afterwards, the post-surgery patient is more intelligent. Some see this part of the story as an example of continuous personal identity despite radical change. However, eventually, the post-operative patient begins to deteriorate, resulting in a less intelligent individual. Unlike the identity-preserving improvement, this deterioration is cited as a personal death.

This example suggests the broader significance of the effect of direction of change on personal identity intuitions. These intuitive judgments can underlie a variety of more practical judgments about the self and personal identity. Extreme effects of mental disease or deterioration can seem to disrupt identity. But similarly large cognitive changes (eg, brought about through deep-brain stimulation) are often treated as obviously preserving personal identity, both when they restore previous cognitive functioning, and when they enhance it beyond previous capacities.

The experiments discussed so far indicate that direction of change affects intuitions about personal identity, but a crucial question remains about whether direction of change is really relevant to the actual personal identity relation. It might seem like extreme deteriorations disrupt personal identity, but is this simply an error of judgment?

There are noteworthy implications in either case. First, suppose direction of change is irrelevant to personal identity. In that case, the finding that direction of change impacts attributions of identity in these thought experiments reveals that such attributions are produced, in part, by an irrelevant factor. This gives a reason to doubt the status of these commonly experienced intuitions about seminal thought experiments – and also the status of other personal-identity intuitions driven by direction of change.

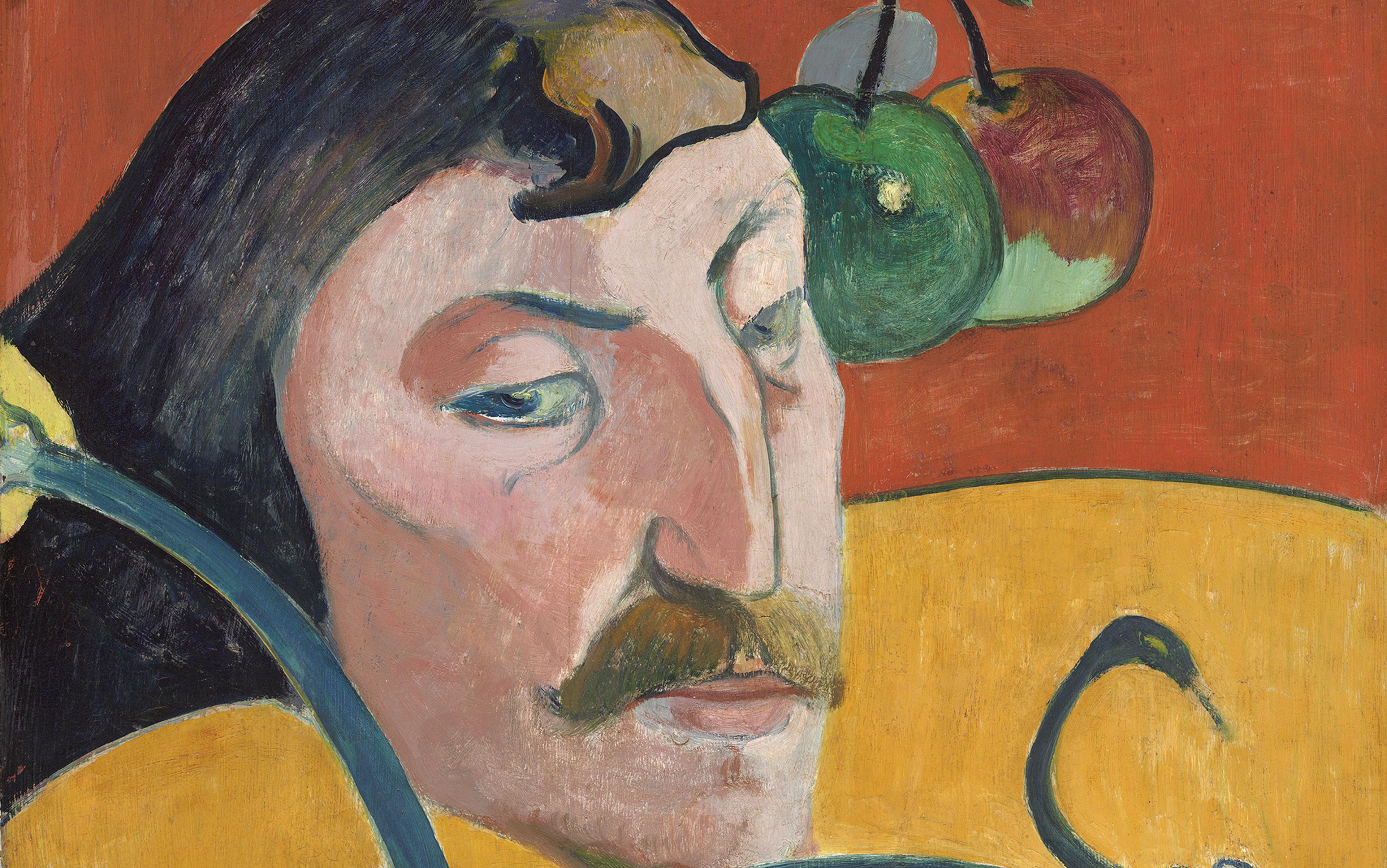

The old Nobleman cannot release his wife from her promise to the young Nobleman; yet his wife is still his wife

Philosophers have long used thought experiments to elicit intuitions about personal identity. Perhaps the most famous is John Locke’s example of the prince and the cobbler. When imagining that a prince’s mind were to enter a cobbler’s body, most are inclined to regard the man with the cobbler’s body and prince’s mind to be the same person as the prince. Such thought experiments provide intuitive data, one source of evidence about the nature of personal identity. For example, from the prince and cobbler intuition, we infer the importance of psychological properties to personal identity. If it turns out that an irrelevant factor systematically skews our intuitions about certain cases, then we should be more skeptical about conclusions drawn from those thought experiments.

Now consider the alternative: suppose direction of change is relevant to personal identity. One challenge for this view is to make sense of some seemingly plausible ways in which the deteriorated individual still seems to be the same person as the earlier individual in the vignettes. For example, even if the post-accident man is no longer Gage, it does seem that he is still the son of pre-accident Gage’s mother, that he owns the same house, and that he owes the same taxes. Perhaps someone who accepts that the post-accident man is not Gage would just reject these other judgments.

Alternatively, one might allow that certain relations or properties stand aside from personal identity. Perhaps (for example) the post-accident man is no longer the pre-accident Gage in some sense, but the pre- and post-accident Gage remain identical to each other in another sense relevant to tax obligations and property ownership. The old Nobleman might not be the young Nobleman in the sense that he cannot release his wife from her promise; yet he does appear to be identical to him in the sense that his wife is still his wife.

Whatever turns out to be the best solution to these puzzles of personal identity, the evidence from experimental philosophy so far indicates that direction of change plays a crucial role in judgments about whether we are dealing with the same person or not after the change. The surprising conclusion is that you can undergo a fundamental transformation of character and still be judged to be the same person, provided that the transformation is in the right direction.