There are currently 43.7 million refugees worldwide. These are people who have been forced to flee their home countries due to severe threats to their lives, human rights and basic needs. Yet, having fled in search of safety, they have not always found it. Instead, the vast majority live in squalid and dangerous camps or face destitution in urban areas in regions neighbouring their own states in the Global South. In these conditions, refugees continue to face severe human rights violations. A small minority undertake perilous journeys to find adequate safety in the Global North. Thousands lose their lives on the way, every year.

How should states in the Global North respond to this situation? This question polarises debate. Some philosophers, like Peter Singer, argue that states must admit refugees until the point of societal collapse; others argue that states are not necessarily obligated to admit a single refugee. Some politicians advocate for expansive resettlement, others seek to prevent refugees from seeking asylum at the border, or even deport them. Some citizens march the streets proclaiming ‘refugees welcome here’, others attempt to burn down a hotel with refugees inside. Some states have welcomed more than a million refugees, others build concrete walls and barbed wire fences.

In the face of such volatile disagreement, there is an urgent need for an understanding and agreement on what an ethical response to refugees would be.

To achieve this agreement, we must reach across divides in current debates to find common ground and base our approach on widely shared commitments. In this spirit, we can grant that states have a right to control their borders and immigration. The question of obligations to refugees is often tangled up with questions of whether states have a right to control borders. But these are distinct questions. You can believe that states have a right to control borders and immigration, yet still agree that states have obligations to protect refugees. So, we can move past the broader distracting and volatile debate on immigration, and focus on obligations to refugees specifically.

Refugees are migrants, but only insofar as they have fled their own countries. The majority migrate no further. Refugees are distinct, as recognised in international law, because they have been forced to flee their own states due to severe threats. Their own state is unwilling or unable to adequately protect them, so they are forced to seek safety elsewhere. This distinguishes refugees from migrants who may not be forcibly displaced and unable to return, but who migrate for other reasons. Refugees therefore have particularly urgent claims to protection and potential admission.

If an innocent person is in desperate need and you can help at little cost to yourself, it would be wrong to refuse

To reach agreement on obligations to such refugees, these obligations must themselves be based on widely shared core moral commitments (that is, basic commitments fundamental to common morality, as well as endorsed by all plausible normative ethical theories and the Abrahamic religions, to which the majority of the world adheres). The first commitment is the moral prohibition on harming or violating the rights of innocent people without substantial justification. For example, it is widely accepted that it would be wrong to physically abuse and then imprison an innocent person without trial for no adequate reason. This commitment grounds our negative moral obligations: obligations to not perform acts that would harm or violate the rights of innocent people. Such negative obligations are widely agreed to be particularly strong.

The second commitment is the principle (sometimes called the humanitarian or Samaritan principle) that if an innocent person is in desperate need of help and you can easily help them at little cost to yourself, it would be wrong to refuse to help and let them needlessly suffer. To take Singer’s famous example, if you saw a small child drowning in a shallow pond, and you could save them simply by pulling them to safety, it would be wrong to do nothing, stand by and let them drown. This commitment grounds our positive moral obligations: obligations to perform acts that would help or otherwise benefit others. These positive obligations are also widely accepted.

So what are the obligations specifically owed to refugees? To answer this question, it is essential to focus our attention on the situation and experiences of refugees themselves. This will reveal morally significant features that ought to be recognised and taken into account, thereby helping us understand our obligations towards them. Once understood, these obligations will form the components of what an ethical response towards refugees would be.

The first morally significant feature of refugees’ situation is that states in the Global North are by no means mere innocent bystanders simply overlooking the harms that refugees face. Rather, many states actively respond to refugees seeking safety with the following practices:

Border violence: violence against refugees is pervasive at European and US borders. In the most extreme cases, refugees are beaten to death or shot by border guards. In Calais, France, UK-funded riot police reportedly use extreme violence including severe beatings. And along Greece’s newly-built 40 km border wall with Turkey, border officials reportedly assault refugees, causing grave injuries (including broken spines), and subject them to degrading treatment – in particular, stripping them naked – before forcing them back into Turkey.

Detention: in a 2017 arrangement between Libya and Italy, and other EU states, refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean Sea to find safety in Europe are intercepted and returned, to be confined in detention centres on the Libyan coast. In these centres, refugees are deprived of their liberty indefinitely, and face overcrowding, disease, starvation and death, as well as torture, rape and even being traded as slaves.

Encampment: as part of the 2016 EU-Turkey deal, refugees who cross the Aegean Sea from Turkey and arrive on the Greek islands are forcibly enclosed in camps and ‘controlled access centres’, denying their free movement. Here, thousands of refugees, including women and children, have faced squalid and unsanitary conditions, and extensive human rights violations, including pervasive sexual violence.

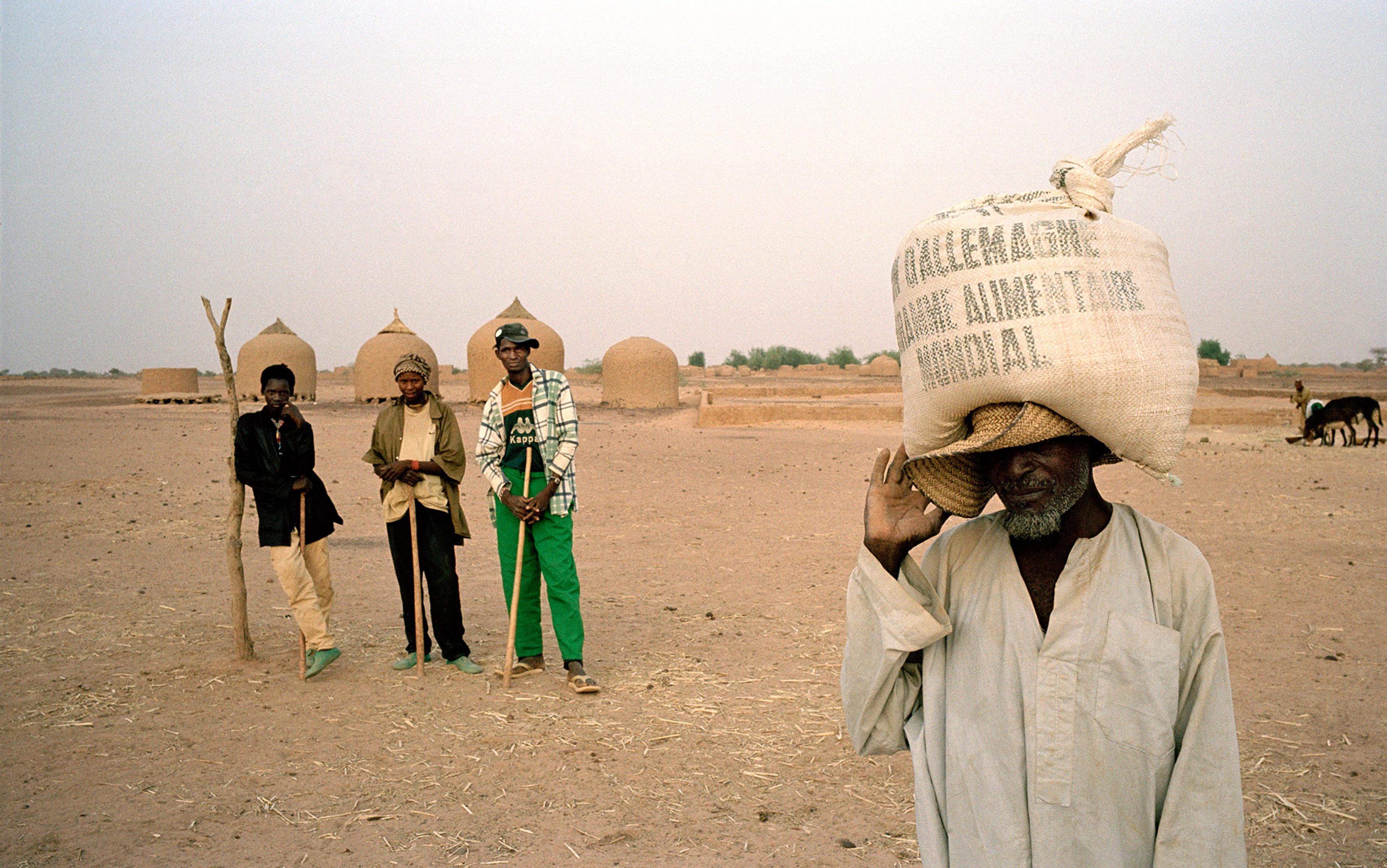

Containment: containment policies forcibly contain refugees in regions in the Global South, away from Northern territories, by shutting down migratory routes to safety. In areas of containment, refugees endure severe harms. For instance, the arrangement with Libya blocks the main migratory route from North Africa to Europe, and so contains refugees in those regions where they face extensive human rights violations. And the EU-Turkey refugee deal blocks that main migratory route to safety in Europe and so contains refugees in regions in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, where they face extreme poverty and human rights violations in urban areas or camps.

With unlimited space and time, we could consider many, many other practices used against refugees. The point, however, is already clear. Many states in the Global North adopt policies and practices that result in extensive mental and physical suffering and severe human rights violations for refugees. These states are thus not merely failing to help those refugees asking for safety but are in fact actively harming them. Border violence, detention and encampment straightforwardly harm refugees: they cause them to be far worse off than they would have been otherwise. And containment also harms refugees by forcibly denying their only escape from severe harms, ensuring they instead suffer those otherwise avoidable harms. Containment is the ethical equivalent of blocking the fire escape of a burning building, ensuring that those who could have otherwise escaped are trapped, or holding an innocent child at arm’s length in a pond where they may drown, preventing them swimming to safety onto your dry land.

Funding infrastructure to protect refugees in regions near their states of origin disincentivises onward journeys

States and their citizens may have a right to control their borders, based on legitimate political, economic and cultural interests, but can this justify such harms to refugees? Evidence shows that refugees can and do provide significant contributions to states in the Global North, especially advanced capitalist economies with ageing populations. Even if protecting refugees would require some costs, are these costs morally important enough to outweigh refugees’ urgent needs for protection, let alone morally important enough to justify harming them? We already accept it would be wrong for states to aggress against other states and harm and violate the rights of foreign populations, even if that would greatly serve their political, economic and cultural interests.

Current practices also cause unnecessary suffering. They are hugely expensive (the EU-Turkey deal alone cost €6 billion), and largely ineffective in the long term: they do nothing to mitigate refugees’ needs to seek safety, but often serve only to fuel smuggling operations, and make refugees’ journeys even more lethal (more people died crossing borders in 2023 and 2024 than in any previous years on record). By contrast, safe routes would provide an alternative to irregular border crossings, and funding infrastructure to protect refugees’ wellbeing and human rights in regions near their states of origin demonstrably disincentivises onward journeys.

If states have the resources to fund practices that harm refugees, they can instead fund practices that help refugees that would also, and more effectively, discourage dangerous migratory journeys. The suffering refugees endure today because of current practices is therefore needless and avoidable. It is also grossly disproportionate. Compare the supposed costs of protecting a number of refugees within our political communities relative to the harms caused to those refugees by current practices to prevent them arriving, including immense mental and physical suffering, severe rights violations and, in some cases, death. Finally, these refugees are, of course, innocent people, who, through no fault of their own, face significant threats and have no reasonable alternative but to seek safety in Global North states. To not only refuse to help but instead harm these innocent people – men, women and children alike – ought to strike us as unconscionable.

Current practices therefore cause unnecessary and disproportionate harm to innocent people. For this reason, they cannot be justified by a right to control borders. Instead, these practices are unjustified and, almost certainly, unjustifiable.

Northern states are thus not simply innocent bystanders but are instead currently unjustifiably harming innocent people who are asking for our help. Focusing on this feature of the situation therefore helps us understand states’ negative obligations: not to harm or violate the rights of innocent refugees. These obligations are the first foundational component of an ethical response.

The second morally significant feature of the situation of refugees is that they endure human rights violations both in their home countries and while they are displaced. Most refugees under the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) mandate come from just six countries: Afghanistan, Syria, Ukraine, Venezuela, South Sudan and Myanmar. In these countries, refugees are victims of, and are fleeing, severe violations variously including war, attacks on civilian populations, arbitrary detention, extrajudicial executions, generalised violence, persecution, cruel and degrading treatment, physical abuse and violence, rape and gender-based violence, torture, enslavement, mass murder, ethnic cleansing and potential genocide.

Then, having fled these threats, the vast majority of refugees (75 per cent) are displaced into developing states in the Global South. There, as Serena Parekh’s analysis identifies, they effectively face only three options:

- A life in camps, where refugees endure a passive impoverished existence and extensive human rights violations for prolonged periods.

- A precarious existence in urban areas, where refugees endure violence, harassment, discrimination, restricted labour market access, extreme poverty, exploitation and homelessness without adequate protection from domestic authorities.

Or - Perilous journeys to the Global North, during which refugees face violence, torture, rape, forced labour and exploitation from traffickers, criminal gangs, state police and/or border officials (with unaccompanied refugee children at particular risk), and thousands die en route.

Which option would you choose? This is the choice most refugees face. They endure severe human rights violations within their own state, only to be then displaced into a situation with no adequate state protection, to face further violations either in camps, urban areas, or on life-threatening journeys.

These human rights violations involve serious harms beyond physical suffering alone. Refugees’ autonomy is violated as their control over their own lives is devastated and they are subjected to the domination and control of others; their dignity is violated as they endure degrading treatment and conditions, and their moral worth is violated as they are not treated and respected as equal human beings, but subjected to egregious abuses and treated as inferior.

Refugees also experience what Hannah Arendt, in her analysis of refugee situations in the 20th century, identified as ‘rightlessness’. This meant that refugees, who fled their own state and were not granted protection by another, existed in a situation where their human rights seemed to vanish: they were subjected to extensive abuses with impunity and without any way to claim their rights or have those violations redressed. The same is true today. Though refugees have human rights in principle, many are unable to enjoy those rights (even basic rights against torture and sexual violence) because they are unprotected and systematically violated. As a result, those rights are essentially meaningless for refugees.

Imagine your own state has collapsed, and there is no UK state official or embassy you can appeal to

To grasp this idea of rightlessness, imagine you are a UK citizen. Now consider your human right against cruel and degrading treatment. As a UK citizen, there is a huge infrastructure of state protection in place including criminal laws, a complex legal system with legal penalties and disincentives, law enforcement, and a vast political and economic system to facilitate this, which functions to protect your right. As a result, you will typically fully enjoy your human right against cruel and degrading treatment throughout your whole life (you likely barely even notice or worry about this right).

Now imagine the UK descends into civil war. The government begins to violently repress citizens’ rights before eventually collapsing, resulting in widespread violence across the country. You and your family, fearful for your lives, make the agonising decision to leave the UK in the hope of finding safety elsewhere. There are no safe routes to leave. Yet, you manage to survive a dangerous small-boat journey across the channel to France. You end up in a refugee camp in Calais alongside thousands of other UK refugees.

Now imagine someone (a trafficker, a criminal, or a border or camp official) threatens you. There is no protective infrastructure in place. Your own state has collapsed and offers no protection, and there is no UK state official or embassy you can appeal to. You have not been granted formal protection by the French government, and the local authorities and police force are absent, overstretched, not interested or even hostile. There is no one to turn to. In this situation, your rights can (and, likely, will) be violated by others with ease, and you will have no protection or assistance. As such, your human right against cruel and degrading treatment effectively means nothing: you are unable to enjoy this right, and you are, in this sense, rightless. This is the phenomenon of rightlessness that Arendt identified and which the majority of refugees currently face.

Focusing on this second feature of refugees’ situation – the extensive human rights violations they endure, both in their own states and while displaced – helps us understand states’ positive obligations towards them. Refugees are in urgent need of protection. States in the Global North – among the most stable and affluent states on the globe – have the capacity and resources to provide it at comparatively little cost to themselves (either through humanitarian assistance, resettlement or granting asylum at the border). These states therefore have positive obligations to do so. And, once we fully grasp the harms and rightlessness that refugees endure, we see that refugees have much more urgent claims to be protected, not just from physical suffering, but also from further severe harms and injustices.

Focusing closely on important features of the situation of refugees has therefore revealed an understanding of the moral obligations that states have towards them:

- Negative obligations not to harm or violate the rights of innocent refugees.

- Positive obligations to protect refugees, to alleviate not only physical harms but also harms to their autonomy, dignity and moral worth, and secure their human rights.

We have now arrived at an understanding of the negative and positive obligations, based on our core commitments, that together form the basic components of what an ethical response to refugees would be.

What would implementing this ethical response look like? The negative obligations would rule out harmful practices. State policies and oversight would prohibit tactics of violence and abuse at the border, and ensure respect for refugees’ rights. The interception, return and detention of refugees, as in Libya, would end as a practice, with currently incarcerated refugees evacuated to safety. Forced encampment would also cease. And containment would be prohibited as a practice: refugees would not be forcibly prevented from escaping severe threats; instead, their human rights to seek asylum would be respected.

The positive obligations would also rule out particular practices as inadequate. Camps may cover subsistence needs in the short term, but long-term encampment fails to provide an autonomous or dignified existence, or human rights protection, and does not treat refugees as moral equals but as undesirable elements to be herded away. Forced relocation schemes, which deport refugees against their will to states they do not wish to be in, similarly fail to provide an autonomous and dignified existence or adequate human rights protection, and do not treat refugees as moral equals, but akin to toxic waste to be exported away.

Instead, the positive obligations would require alternative responses. Active resettlement of refugees into Northern states would provide an autonomous existence where refugees could live and rebuild their lives according to their wishes, a dignified existence away from squalid camps and urban destitution, as well as human rights protection. Resettlement further respects refugees as worthy of moral consideration and of inclusion as moral, social and political equals. Providing safe and regular routes would also be required. At present, the only way a refugee can claim asylum in Northern states is by physically setting foot on those territories. This incentivises often-lethal journeys. For an alternative safe route, issuing humanitarian visas as valid documentation to travel safely on airlines and trains would enable refugees’ autonomy and dignity in travel to safety, safeguard their rights, and respect them as moral equals worthy of protection.

Eurostar even offered free rail travel for Ukrainian refugees to the UK

The above proposals might be dismissed as a naive wishlist that ignores the political realities of the contemporary world. The 44 million refugees worldwide are roughly 0.5 per cent of the global population. This is often framed as an unprecedented ‘crisis’, but this invites alarmism, fatalism or harmful, knee-jerk responses. Larger displacements have been addressed in our history (there were around 200 million refugees after the Second World War, or 10 per cent of global population), and we have a wide variety of policy tools available. Feasibly expanding resettlement across Northern states through a multilaterally coordinated agreement could save millions of the most vulnerable. Providing safe routes would remove the desperation exploited by trafficking gangs and the huge state expenditure on combatting them. And many refugees can be protected in regions closer to their states of origin through modest increases in foreign assistance in grants to host states and fulfilling the (chronically underfunded) budget of the UNHCR. An ethical response is therefore not only urgently required but also within our reach.

In fact, it is already a reality – at least for Ukrainian refugees. There are no Ukrainian refugees beaten up or killed at Northern state borders, nor drowning en route. There are no Ukrainians imprisoned indefinitely and abused in detention centres, or enclosed into camps, or forcibly contained in regions facing severe threats to their human rights. Instead, immediate protection has been provided to millions. The EU Council activated its Temporary Protection Directive (available since 2001, but triggered only in 2022), granting all Ukrainian refugees the right to travel freely to, and access employment, housing, healthcare, education and social welfare in, any and all EU states. The UK provided visa schemes allowing hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees to apply online for free, and then board commercial flights or other transport to the UK and stay for at least three years with immediate rights to work and access to public services. Eurostar even offered free rail travel for Ukrainian refugees to the UK.

This response should be rightly celebrated as one where the negative and positive obligations towards refugees were recognised and acted upon. An ethical response was achieved with millions protected. This response also proved that the supposed costs of protecting refugees were agreed to be morally irrelevant in the face of urgent obligations towards them, and that expansive protection measures were not idealistic, infeasible or too demanding, but immediately implementable.

Since all human beings are moral equals, there can be no moral difference between Ukrainian refugees and non-Ukrainian refugees facing equal threats that could justify such divergent responses towards them. An ethical response, demonstrated to be possible towards Ukrainian refugees, can and ought to be expanded to all.