On a chalk down beneath an iron-age hillfort and a grove of beech trees near my home in Hampshire in the south of England, a labyrinth has been cut into the turf. It looks almost like a tinted engraving. The short-cropped grass pillows up around the narrow pathways as if they had been pressed into something soft, and in the right light the milky soil shines through.

On the morning of my wedding, I walked the folded path to its centre. I say ‘walked’, but I was in a bit of a rush so it was more a trot – but I wanted to finish the thing, so I traced the path back out again. I could never have gotten myself lost. In the Mizmaze there is one entrance and one exit, and one route between them: by one definition this makes it a unicursal ‘labyrinth’ rather than a multicursal ‘maze’, which presents choices between alternative paths.

After performing my private little ritual, I continued on down the hill to the registery office in town, where I got married. Why had I felt the need to go labyrinth-walking? I am not prone to this sort of behaviour. I feel skeptical about confabulated New Age rites. And yet something about the Mizmaze drew me to it that morning. I wanted to understand what that thing was – to discover what, in human history and psychology, mazes and labyrinths are for.

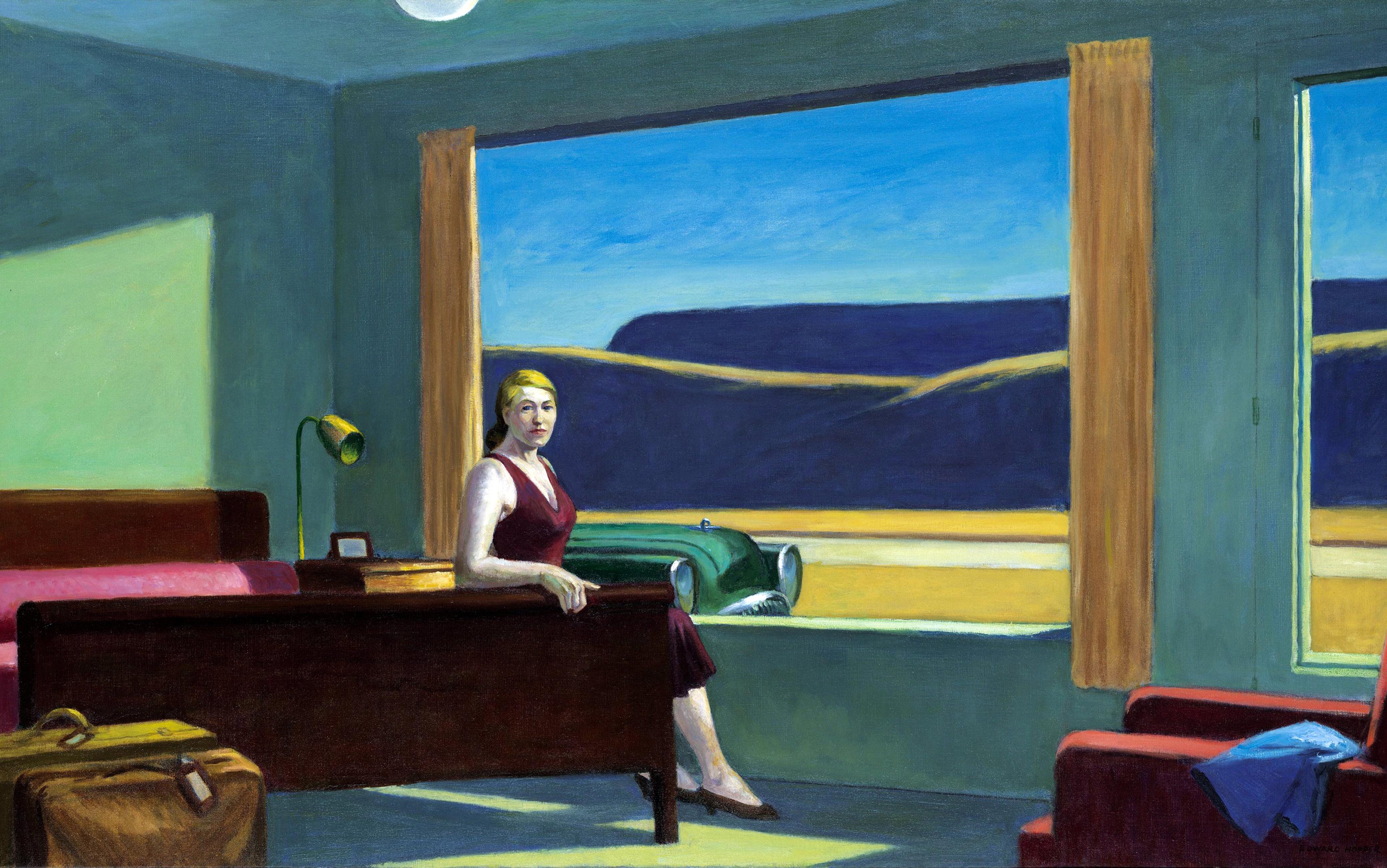

The Mizmaze at St Catherines hill, Hampshire, England. Courtesy Wikipedia.

This is not merely a personal preoccupation. Culturally, mazes are now massively resurgent. Practically every country park has its hedge maze, mirror maze or maize maze – and so do a growing number of churches and cathedrals. In virtual reality, notably, the maze forms the basic substructure of innumerable videogames. So why do mazes draw us in? And what do they do to us while we are there?

Instinctively, we sense that mazes and labyrinths are essentially metaphorical – even if it is not always clear what they represent – which explains why it’s so common to seek the meaning of the maze in myth. According to the ancient Greek story, as retold by the Roman writers Plutarch and Ovid, Minos of Crete demanded a tribute from the city of Athens in the form of seven young men and seven women. They would be imprisoned inside the Labyrinth created by Minos’ brilliant architect Daedalus, and there sacrificed to the Minotaur, a monstrous creature born of the unnatural union between Minos’ wife and a white bull.

The brave and ambitious Theseus gets himself chosen among the Athenians and, on arrival in Crete, seduces Minos’ daughter, Ariadne. She secretly arms him and slips him a ‘clew’ of thread. (This is the old word for a ball or skein of yarn and is, fascinatingly, the origin of the English word ‘clue’.) Theseus kills the Minotaur, escapes the Labyrinth, runs off with Ariadne, and should return home happily – except that he abandons Ariadne on the island of Naxos and then, upon homecoming, forgets to change the colour of the sails on his ship as he promised his father he would do if he survived. On seeing the black canvas, the old man drowns himself in the sea.

Archaeologists have long sought to locate Minos’ maze, working on the principle that, if amateurs such as Frank Calvert and Heinrich Schliemann had found the ‘real’ Troy, why should they not find the original Labyrinth?

Wasn’t the five-acre Minoan site that the archaeologist Arthur Evans unearthed at Knossos in the 1900s bafflingly labyrinthine? Was there not a shrine room where the Minoan motif of the double axe – labrys in Greek – was insistently depicted? Scholars now concede that there might have been some kind of bull cult, but they insist that the etymological link with ‘labyrinth’ is only speculative. The labrys symbol was regionally ubiquitous, rather like the ‘evil eye’ motif in Greece today.

They point instead to the shaped and worked cave complex at Gortyn, 20 miles from Knossos. Archaeologically, ‘it is extremely difficult to say that a Labyrinth ever existed’, observed the geographer Nicolas Howarth of the University of Oxford who investigated the caves in 2009 – though in an interview with The Independent newspaper he admitted that the caves were ‘a dark and dangerous place where it is easy to get lost’.

The labyrinth represents ‘a precinct within which evil was contained and into which no evil spirit would dare penetrate’

It is as easy to get lost in arguments over the possible location of the ‘real’ Labyrinth. More important is the labyrinth as it has been imagined. The extraordinary thing about ancient labyrinths is that almost none of those visible today on ancient Cretan coins and Roman mosaics would have required a clew of thread to solve. Before the 15th century, they were all but universally ‘unicursal’: like my Mizmaze, they offer one single-path ‘solution’. They look like a puzzle, seen from above. Experienced from within, however, you could not go wrong.

Of course, even in a unicursal maze you can still be defeated by the Minotaur. In fact, Roman and early Christian mazes frequently corralled a bull-headed figure in labyrinths that were typically placed near the main door, suggesting decorative and apotropaic functions: they welcomed guests by virtue of their beauty, and warded off evil by virtue of their symbolic power. That power is derived, in the way of so much ‘sympathetic magic’ of this kind, from the very representation of the thing that is most feared. As Craig Wright puts it in his authoritative study The Maze and The Warrior (2004), the ancient labyrinth represents ‘a precinct within which evil was contained and into which, paradoxically, no evil spirit would dare penetrate’.

After labyrinths were adopted by churches, paradox remained the source of their strange power. Paradox, and a certain playfully mathematical spirit. The earliest surviving Christian labyrinth is a hyper-geometrical monochrome mosaic. Built for the fourth-century basilica of St Reparatus (though now in Algiers Cathedral), it looks almost like a word-search puzzle inside an optical illusion. It replaces the central minotaur figure with a word-grid that jumbles the words SANCTA ECLESIA, or ‘holy church’ – SANCT A being laid out as a double palindrome in the form of a cross. Like a palindrome, the labyrinth can be traversed in two directions. It can be read as a symbol of the battle against evil and darkness, and, conversely, of the pilgrim’s journey towards spiritual perfection and light.

The labyrinth lends itself to such puzzle-making – and, by counting the ‘coils’ from which it is constructed, to numerology. What became the standard Christian pattern showed seven coils, signifying the seven ‘spheres’ of the Universe (the five known planets, plus the Sun and Moon). Sometimes, 11 coils were shown – signifying sin (11 lying between the Ten Commandments and Twelve Apostles). If you counted the central sanctuary as a 12th coil, the pilgrim could pass through the sinful world to arrive at a holy place.

Pilgrimage might have been the point. It is hard to be sure how labyrinths were used – it is like finding a playing board without any counters or instructions. But there are clues. The greatest of all Christian labyrinths was set into the nave floor of Chartres Cathedral near Paris soon after 1215. Its centre used to contain a brass medallion of a minotaur. When the Revolutionaries took it to make cannons, in 1792, they observed that it was worn away. Had worshippers tracing the path to its centre rubbed the lucky minotaur off the medallion?

Such ‘pilgrimages’ could have been common. At Sens Cathedral in Burgundy, an 18th-century inscription explains that it took 2,000 steps and one hour to ‘cross’ the labyrinth. This could be true only if the traverse was done at a crawl, in keeping with the English medieval tradition of penitentially ‘creeping to the cross’ on Good Friday. And there survives an extraordinary eyewitness record of a game played at Auxerre Cathedral, also in Burgundy. According to the Abbé Jean Lebeuf, writing in 1726, the clergy would perform an Easter ring-dance around the labyrinth, taking turns to return passes of a leather ball to the dean, who stood in the middle. Did the ball represent the ball of thread that Ariadne gave to Theseus? The rising sun on Easter morning? Or was it just enormous fun after the trials of Lent?

Game-playing and mazes have long been intertwined, but the maze as game comes to the fore in the Renaissance. It was then that the unicursal labyrinth finally changed into something that would have tested Ariadne’s thread. In box gardens and in landscape paintings, mazes suddenly acquire multiple alternative paths. Junctions. Nodes. The delicious possibility of being lost. The unicursal labyrinth as a test of courage, faith and endurance became the multicursal maze – a test of the intellect and reason.

This testing game, this playful puzzling with a dash of risk, is not restricted to the ‘running’ of a maze, but is inherent in the genius of any multicursal maze’s design. The Germans coined a new word for it: the Irrgarten, or Garden of Errors. In English, the newly preferred term of ‘maze’ was derived from an older English root implying a state of delusion or bewilderment. To be ‘mazed’ or ‘amazed’ implies not merely to be lost but to be at a crisis. To be paralysed with indecision at the junction of paths. On the horns of a dilemma. Paradoxed. The pleasure of this is surely related to the delighted surprise inherent in puns and jokes that rely on double meanings and can help to explain the allure of the multicursal maze.

The maze was a metaphorical testing-ground for resolve, and emphasised the lover’s faithfulness and eroticism

The making of errors now became that most paradoxical thing, scary fun. Wright calls the hedge maze, created at Hampton Court Palace near London in 1689, ‘a 17th-century rollercoaster on a two-dimensional plane’. It made for a thrillingly scary and conspicuously flirtatious outing. In Renaissance mazes, the Minotaur as tutelary deity cedes his place to Cupid. Meanwhile, the real-world, turf-cut mazes that began to proliferate across England (the ancestors of my Mizmaze), were seemingly being used for lovers’ games.

There are only clues as to what might have taken place. The 18th-century British antiquarian William Stukeley poignantly noted that ‘lovers of antiquity, especially of the inferior classes, always speak of ‘em [mazes] with great pleasure, as if there was something extraordinary in the thing, though they cannot tell what’. A correspondent to Notes and Queries in 1870 refers to the near-extinction of ‘the old British game of Troy’ once played on the turf mazes known as ‘Troytowns’. She doesn’t say more but, intriguingly, the paths of one ‘Troy Town’ at Dalby, in North Yorkshire, are cambered as if to allow sprinting.

The best evidence comes from Saffron Walden, the largest English maze. According to folklore, a girl would stand in the centre while local boys dashed towards her. This chimes with Scandinavian oral histories about lovers using mazes for games connected with spring festivities. The maze was still a metaphorical testing-ground for resolve, but now it emphasised the lover’s faithfulness more than the warrior’s bravery or the penitent’s sincerity. And the lover’s eroticism. The multicursal maze offers concealment and discovery, closeness and separation, the opportunity to be baulked and rewarded. The seven-coil labyrinth becomes a dance of the seven veils.

Through all these transformations, the maze remains inherently metaphorical and paradoxical. It insists on being read, and read symbolically. This is also true in modern labyrinths, but something crucial shifts. The symbol at its centre – in labyrinth terminology, the home, goal, sanctuary or temenos – is no longer the Minotaur or Cupid. It is an empty space waiting to be inhabited by the self.

At the hedge maze at Longleat in Wiltshire, you encounter close, intense silences as you run the maze, but they are frequently punctured by sudden, loud shrieks. Even a play-park maze is paradoxical. On the afternoon I walked it, I spoke to the warden on duty, Francesca. Many visitors complain that they did not get lost for long enough, she told me but, upon reaching the central redoubt, almost all opt to take the short, straight, signposted path to the exit, not to re-enter the maze. As we spoke, her radio crackled and she turned to me apologetically. ‘There’s a lost child now.’ Lost by the grandmother who couldn’t squeeze through the littlest gaps in the hedge, it turned out. The little girl did not feel any more lost than she wanted to be.

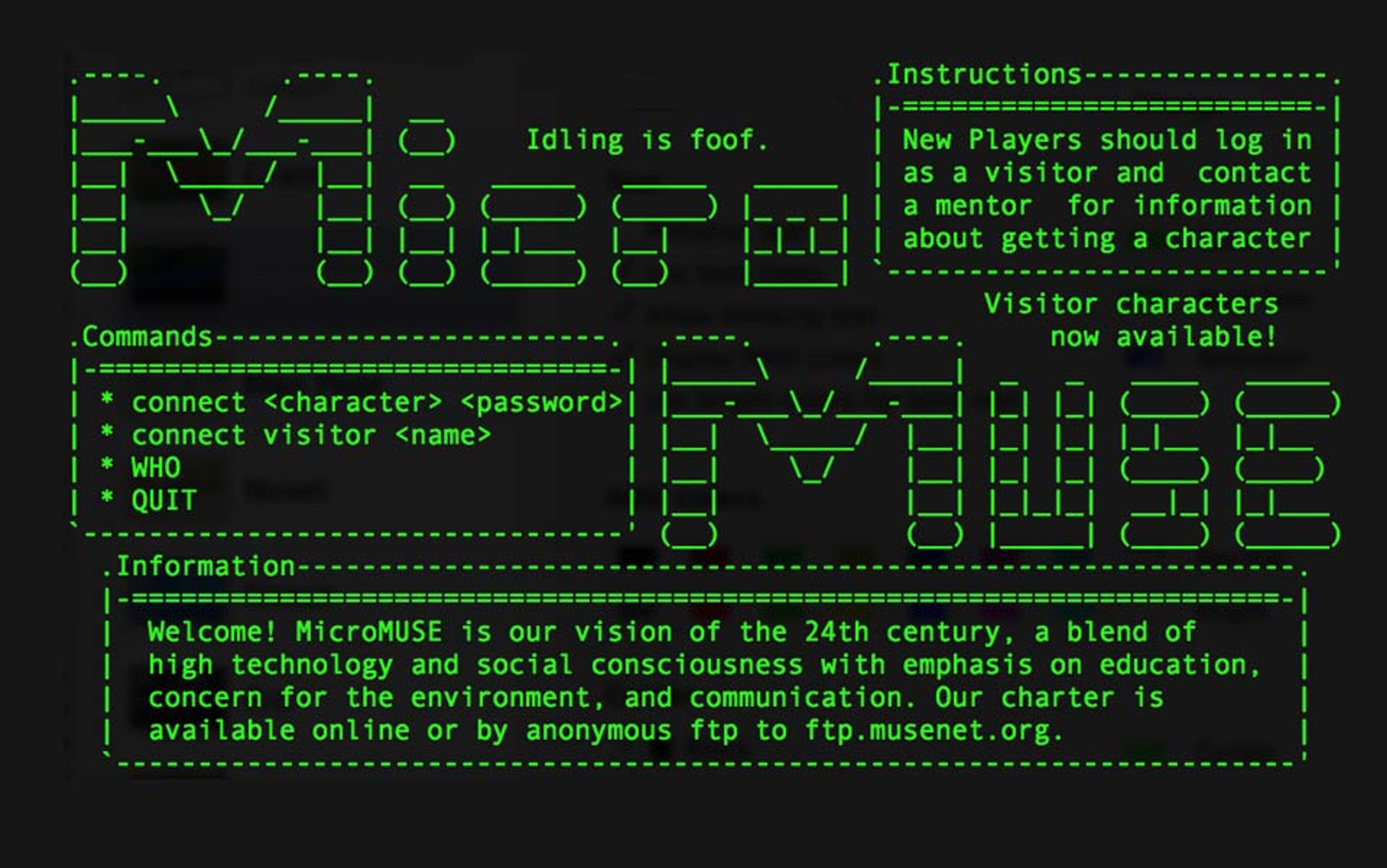

No more do the countless millions of videogamers who have entered mazes since Atari launched Gotcha in October 1973 – which was one month after I was born. Since then, and especially since Pac-Man (1980), the maze as a basic structure of the videogame has become so commonplace that it seems almost natural. The maze offers the ludic pleasure of being at once lost and questing – along with a satisfying opportunity to kill the monster within. (After Doom, in 1993, multiplayer first-person shooters offered the even more satisfying opportunity of entering the maze so as to kill your own friends.) The correspondences between videogames and mazes run deeper than the similar pleasures they offer, however. Like a maze, virtual reality is designed reality; in the gamespace, all structures and all landscapes become mazes, and the only way to exit is to turn off the machine.

Not all contemporary mazes are hedonistic. The other type is far closer to the medieval labyrinth than the Renaissance pleasure garden or videogame – both in being defiantly unicursal and in being avowedly spiritually transformative. The first of these mazes was installed in Grace Cathedral in San Francisco in 1991, copying the Chartres pattern. Under this Episcopal cathedral’s former canon, Lauren Artress, this became the model for a worldwide programme of contemplative labyrinth-walking. It was a form of spiritual exercise. You could even buy labyrinth mats by mail order.

The practice spread rapidly: for Helen Curry of the Labyrinth Society in New York state, a non-specific faith group dedicated to walking labyrinths, ‘No other tool can so successfully bring into alignment the many aspects of our being and teach us so clearly that we are all on the same path.’ Pun presumably intended.

‘In the labyrinth you don’t lose yourself. You find yourself’

Meditative labyrinths have spread to hospices, lighthouses and theology colleges. There was a welcoming labyrinth at the 2002 Salt Lake City Winter Olympics, and another near New York’s Ground Zero. At Slangkop Lighthouse, near Cape Town, there is even a Reconciliation Labyrinth. Neatly, its two entrances lead to the same centre.

Labyrinth-walking has become a form of New Age practice. Clive Johnson, the enthusiastic author of Labyrinth Alpha-Omega (2017), suggests coming to the labyrinth with a question, maintaining ‘soft eyes’ and waiting until you feel the urge to enter before stepping into the ‘liminal space’. He quotes the labyrinth scholar Hermann Kern, approvingly: ‘In the labyrinth you don’t lose yourself. You find yourself.’

Freud’s dissenting colleague Carl Jung would have agreed. For him, the ‘primordial image’ of the labyrinth represented the unconscious mind, in particular the ease with which it could be penetrated by the ‘uncanny and alien’. It also symbolised psychoanalysis itself: Jung once described a patient’s symptoms as offering the ‘Ariadne thread’ that would guide the analyst. ‘In all cultures, the labyrinth has the meaning of an entangling and confusing representation of the world of matriarchal consciousness,’ he elaborated in Man and His Symbols (1964); ‘it can be traversed only by those who are ready for a special initiation into the mysterious world of the collective unconscious.’

The labyrinth roils with Jungian symbolism like a deck of tarot cards. There is the roaming, libidinous, shameful monster that must be evaded or destroyed, and the anima-like, eroticised saviour-figure of Ariadne. There is the ‘indirect course’ or Umweg of the libido, which Jung described as a ‘way of sorrow’, and the elusiveness of the solution. There is also the disorientation that the maze so paradoxically produces out of the very geometry of which it is constituted; my own nightmares, when I have them, often take place in labyrinths. At night, Jung might say, we roam the mazes of our own unconscious minds seeking the process of individuation that would liberate us.

In Jung’s maze, we become our own Ariadne, and our own analyst. Was this the purpose to which I had put the Mizmaze? It felt more instinctive than that. Less metaphorical, if anything, and more physical: it felt as if by walking the labyrinth I was tracing out my feelings about getting married on the ground. A unicursal labyrinth proceeds by repeated coils, meanders and oscillations, and you come out by the same way that you go in. You are always turning but always following the same line, and you reach the sanctuary but do not stay there. The piled-up paradoxes felt like metaphors that might express and somehow unite what lay behind me and what was coming up ahead. I wasn’t finding myself in the sanctuary of the Mizmaze. I was leaving a piece of myself behind.