Courtesy Activision

A lot of terrible things happen to video-game characters. In the early days of the form, Italian plumbers were squashed by barrels, loveable hedgehogs impaled on spikes, and heroic astronauts exploded. But no game delights in inflicting as much horror on its protagonists as the $10-billion Call of Duty (CoD) franchise.

Originally set in the Second World War, the series took on its current ultra-popular form with Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (2007). Every year brings new CoD games, and the franchise regularly tops charts, racking up more than 175 million sales over the course of the past decade. Each game weaves together a semi-coherent narrative that combines the regular annihilation of its characters at a George R R Martin pace with a wider and more worrying story arc: one of US powerlessness, decline and revenge.

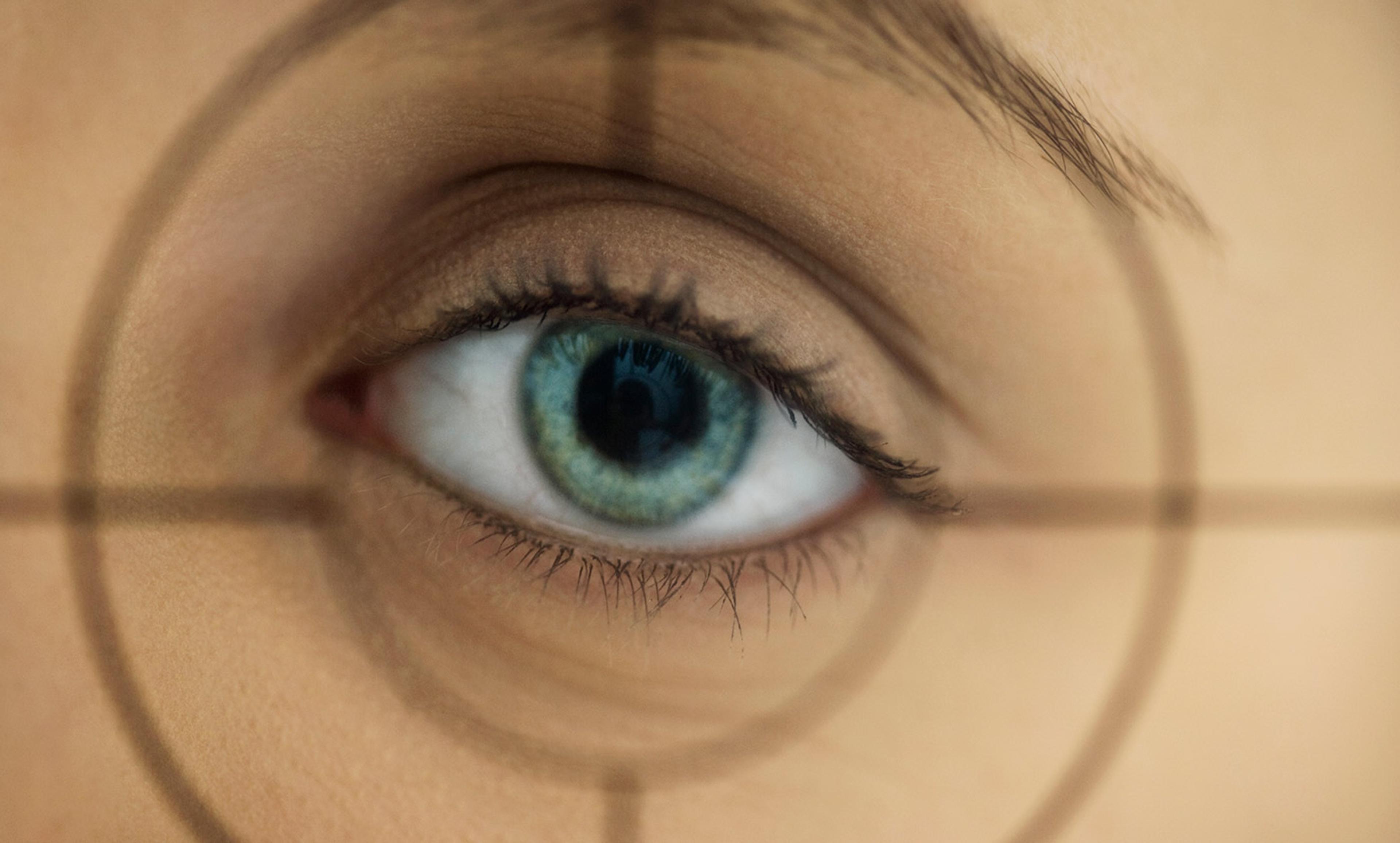

The Call of Duty games are first-person shooters (FPS). ‘First-person’ means that the players see the world through the eyes of their characters – only their hands and weapons are clearly visible. (Some games break this form in third-person cutscenes, but CoD sticks to it resolutely). ‘Shooter’ means that the character interacts with the world almost entirely through the barrel of a gun; the environment, and its endless stream of enemies, exists to be destroyed.

Many FPS are power fantasies, with the child-like joy of being able to murder everything you see. These are little boys’ tales of war, where a finger-gun blows away a thousand foes, and the player is always the actor, never the victim.

Call of Duty frequently reverses that dynamic. In almost every other FPS, the player’s death is a constant possibility, yet those are transient endings, erased from the game’s reality by a simple reload. But in Call of Duty, sufferings both permanent and unavoidable are ineffably worked into the game’s narrative. Although the gameplay is a consistent frenzy of violence inflicted by the player on the world, narrative control – the happy freedom to move, shoot, call in drone strikes, knife people in the back – is regularly snatched back from the players, forcing them into positions of constant helplessness.

Meanwhile, the point of view continuously switches, deliberately and disorientatingly – a CIA agent, a doomed ISS astronaut, a fallen dictator, a SAS operative. Throughout the series, the player’s avatars are repeatedly tortured, nuked, brainwashed, murdered, mutilated and, above all, betrayed – often by their own leadership. If they live, they are depicted as broken, made whole only by vengeance. If they die, another character takes up the mantle of revenge.

Beyond such personal treacheries and dismemberments is a wider depiction of victimhood, not individual but national. The reversal, from active shooter to passive martyr, gets at a lasting psychological truth, which is that however absolute US military superiority is in reality, many Americans feel themselves to be a nation under siege by an ungrateful world, eternally vulnerable.

The original CoD 4: Modern Warfare (2007) begins by depicting US power realistically (enemy tanks are neutralised by man-portable FGM-148 Javelin missiles, enemy soldiers are mowed down en masse by AC-130 Spectre gunships, and the war is far from US shores). Then a nuclear blast kills the first protagonist, shifting the conditions of the game. Alongside him die 30,000 other US troops, their names and ranks scrolling past rapidly on screen, in a plot that turns out to have been orchestrated by a line-up of villains old and new – Russian ultra-nationalists working alongside Islamic terrorists.

The sequels go further. Through a technological magical wand that cripples US defence systems, an army of Russian paratroopers and marines is able to invade Virginia. In the course of MW2 (2009) and MW3 (2011), battles rage along Wall Street, the Brooklyn Bridge and Pennsylvania Avenue, with ‘tens of thousands’ of Americans killed and the day saved only by heroic violence from the US army.

In this timeline, US power is expressly fallen. As the ad copy for Call of Duty: Ghosts (2013) puts it, ‘the balance of global power’ changed forever and a ‘crippled nation’ faces ‘technologically superior’ foes. War, against an array of bogeymen, from insurgent South American powers to the ever-green Russians, has become a constant necessity.

Every indignity inflicted on individual Americans (and the occasional Brit) in the narrative is echoed in the games’ geopolitics: US cities burn in nuclear fire, Mexican border states become a ‘No Man’s Land’, and the US financial and military elite repeatedly betray the nation, and its soldiers.

This might all seem very silly, and it is. I don’t believe that the writers of the game have much more in mind than spectacle when plotting the course of the series, because it certainly does look pretty when great landmarks explode. Token efforts at moral complexity are woven in here and there, from the anti-war quotes that play over every temporary death to the origins of a foe’s plot against the US in the death of his relatives from a US strike.

And yet, Modern Warfare reinforces, consciously or otherwise, the ever-present US myth that the country is an innocent victim in a cruel world. It’s a belief that swelled massively after the attacks of 11 September 2001, but it has always been present. The start of US wars has always been framed by betrayal, real or otherwise, from the actual surprise attacks of Pearl Harbor to the imaginary Spanish super-weapons blamed for the explosion of the USS Maine in 1898 or US President Lyndon B Johnson’s lies around the Gulf of Tonkin. And in Modern Warfare, the killing of US soldiers, especially by illegitimate foes – militias, terrorists, ‘rebel forces’ that make up the mass of Call of Duty’s shooting targets – is taken not just as a consequence of war, but as a crime committed by the enemy.

Coupled with that is the fear of weakness. In a country that outspends all its potential foes put together, nearly half the public believes, according to a recent Gallup poll, that it is ‘just one of several leading military powers’. (Back in the Cold War, the entirely fictitious ‘missile gap’ served the same propagandist purpose, but then, at least, there was the excuse of Soviet opaqueness around what were, in fact, considerably smaller and more backward arsenals than the US possessed.)

Victimhood is only the start. The protagonists of CoD games aren’t stopped by betrayal, injury or even death. Their travails are the necessary prelude to their roaring rampage of vengeance, and their passive suffering doesn’t subvert the fantasy of power but endorses it; every bullet fired is justified by ruined bodies, both politically and personally. CoD’s wars are a hysterically exaggerated reinforcement of national wish-fulfilment, consumed by millions of young US men: they hurt us first, so we get to hurt them back.