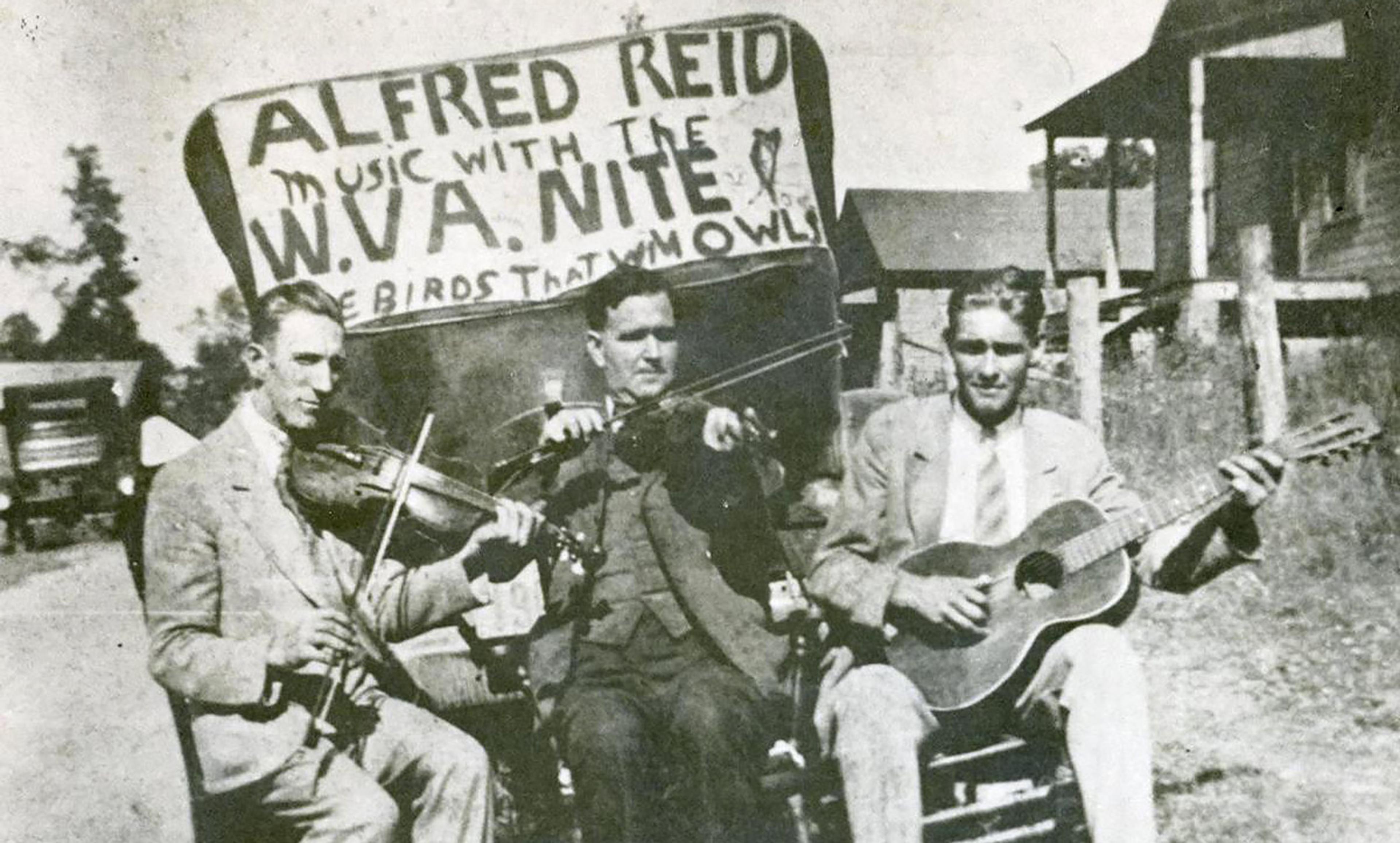

Blind Alfred Reed© and the Virginia Nite Owls c1920. Photo courtesy Goldenseal/East Tennessee State University

When Donald Trump took the first international trip of his presidency to Saudi Arabia in May 2017, another US icon also travelled along as part of the celebration of the alliance between these two countries: the country-music star Toby Keith. For many observers, Keith was a surprise choice for an appearance in a Muslim country, as he rose to conservative prominence in the US through his post-9/11, jingoistic anthems in praise of intervention in the Middle East, such as The Taliban Song (2003) and Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (2002, with its signature warning: ‘We’ll put a boot in your ass. / It’s the American way.’)

Perhaps Keith’s appearance at the Trump inauguration urged the Saudis to make this unusual pick, with them hoping to curry favour by appealing to the new president’s tastes – although Trump has never been a country fan. Maybe the choice acknowledged Keith’s popularity with some members of Trump’s voter base. But, for whatever reason, the singer became pegged as a kind of cultural emissary as a result of this visit. What was he representing and to whom?

Alyssa Rosenberg, writing in The Washington Post in May 2017, speculated that Keith ‘sees himself as an ambassador for a certain version of American society, for cold beers and women in crop-tops and backyard poker games and the redeeming power of Christianity’. Although these positions (and others Keith has taken) do not fit Saudi Arabia’s particular brand of conservatism, they do play well in the US – at least to some voters and listeners. But at the same time, they misrepresent the whole of what country music stands for (or against).

This recent episode does not stand alone in how country music has often been presented to the world. Early on, it was deemed ‘hillbilly music’ by the very recording industry producing it, stereotypically linking it to a supposedly degenerate and backwards culture. We can see this image echoed on the front page of Variety in 1926, where the music critic Abel Green first defines the audience: ‘The “hill-billy” is a North Carolina or Tennessee and adjacent mountaineer type of illiterate white whose creed and allegiance are to the Bible … and the phonograph.’ Then the music got its lashing when Green described it as ‘the sing-song, nasal-twanging vocalising of a Vernon Dalhart or a Carson Robison … reciting the banal lyrics of a Prisoner’s Song or The Death of Floyd Collins …’

These kinds of negative projections of the people who have made country music, and have listened to it, linger even unto today. The stereotype is that they all harbour conservative political and social beliefs, setting them as sexist, racist, jingoistic and fundamentalist Christian by nature. But this image is a lie. For, right from the start, country music spoke up with a progressive voice.

One early example of this is from Blind Alfred Reed, who crafted How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? (1929). The song takes on the unjust practices of groups in power, such as in the lines: ‘preachers preach for gold and not for souls’ and ‘Officers kill without a cause.’ It presents the entirety of the working class as being victimised at the very dawn of the Great Depression. But Reed also wrote the religious song There’ll Be No Distinction There (1929), which illustrated an egalitarian afterlife in the lines: ‘We’ll all sit together in the same kind of pews, / The whites and the coloured folks, the gentiles and the Jews.’ But Reed was not alone in expressing sympathy for the working class or in calling out for a more equitable society: others from this early era – such as Uncle Dave Macon, Fiddlin’ John Carson and Henry Whitter – expressed similar sentiments, just as Johnny Cash, Steve Earle and John Rich have done in later decades.

Country music has also spoken out on women’s issues, such as in Loretta Lynn’s hit The Pill (1975). The song celebrates freedom from pregnancy, with the narrator noting how her husband has always been carefree and unfaithful while she was tied down with ‘a couple [babies] in my arms’ and another one on the way. Lynn’s message here is clear – she despises this kind of unequitable relationship, as she bluntly states in her autobiography Coal Miner’s Daughter (1976): ‘Well, shoot, I don’t believe in double standards, where men can get away with things that women can’t.’ In the country-music market, this song stands out as an unabashed and rather radical call for sexual liberation and biological control, challenging the man’s past sexual prerogative and presenting a situation where the woman may also enjoy a variety of sexual liaisons without the social/economic restrictions that come with pregnancy, childbirth and childcare. Lynn rejoices both in the song and in her own overall personal belief that the contraceptive pill will allow women greater control of their own lives: ‘I really believe in those words. It’s all about how the man keeps the woman barefoot and pregnant over the years. I think it’s great that women have a way of protecting themselves now, without worrying about the man.’ And Lynn has not been alone in advocating for women’s rights, joining others, from Kitty Wells to Margo Price, in pointing out gender prejudices and abuses.

Performers have also taken up racial issues throughout the history of country music. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, Merle Haggard recorded Go Home and Irma Jackson, which both centre on interracial love affairs, with the lyrics siding with the couple, not the prejudice. Both of these songs appeared in the era of Loving v Virginia (1967), the US Supreme Court decision that overturned several states’ laws against miscegenation. Thus, Haggard repeatedly took an explicitly progressive stand at a time when interracial relationships remained contentious, especially in the South. More recently, Garth Brooks, Brad Paisley and Jason Isbell have taken bold stands on race relations in the US.

Country music, from its very beginnings to its latest hits, has ranged about, speaking out on any number of issues and not just with one voice. Many have explored its sonic landscape. Yet when figures such as Keith strut out onto the political stage – whether it be in Washington, DC or Riyadh – too often the mainstream media, Right-wing politicians and others ignorant of the rich and varied history of this essential American music point to them and try to paint it as a conservative-only expression. To counter this false impression, country music deserves better cultural ambassadors, artists who can and have voiced the full range of views that have always been part of the tradition, the full truth of country music.