Listen to this essay

25 minute listen

‘Seal Pup on Beach.’ That’s what the makeshift sign read, on a wooden post along Ireland’s eastern coastline. At the water’s edge, I discovered a pair of volunteers watching over a small, sentient being. It lay hairless, blinking slowly as if struggling to see the world around it. Its pale, almost translucent skin blended with the white rocks on the stony beach. The volunteers told me that the pups’ fur is not waterproof in their first few weeks of life, so they cannot enter the sea. This leaves them entirely vulnerable to predation (often from roaming dogs) as they wait for their mothers to return with food.

And so, the volunteers were standing guard, protecting a soft, fragile being capable of distress, fear and suffering. This may seem an obvious thing to do. But not long ago, the greatest threat to seal pups was humans themselves. Across northern Europe and Canada during the 19th and 20th centuries, workers roamed coastlines and pack ice, beating infant seals to death with clubs. White ice was smeared red. Annual kill rates for seals are estimated in the hundreds of thousands, all done with the purpose of turning them into raw industrial materials for the production of clothing, oil, and meat. Even if their suffering was real, many considered it inconsequential. Seals, like many other creatures, were seen as little more than tools or resources.

However, views of animal suffering and pain soon shifted. In 1881, Henry Wood Elliott reported on the ‘wholesale destruction’ of seals in Alaska, leading to international outcry and the establishment of new treaties. And in ‘The White Seal’ (1893), Rudyard Kipling told a sympathetic story from the perspective of the hunted animals themselves. If someone killed a seal pup today, they would likely be charged in a court of law.

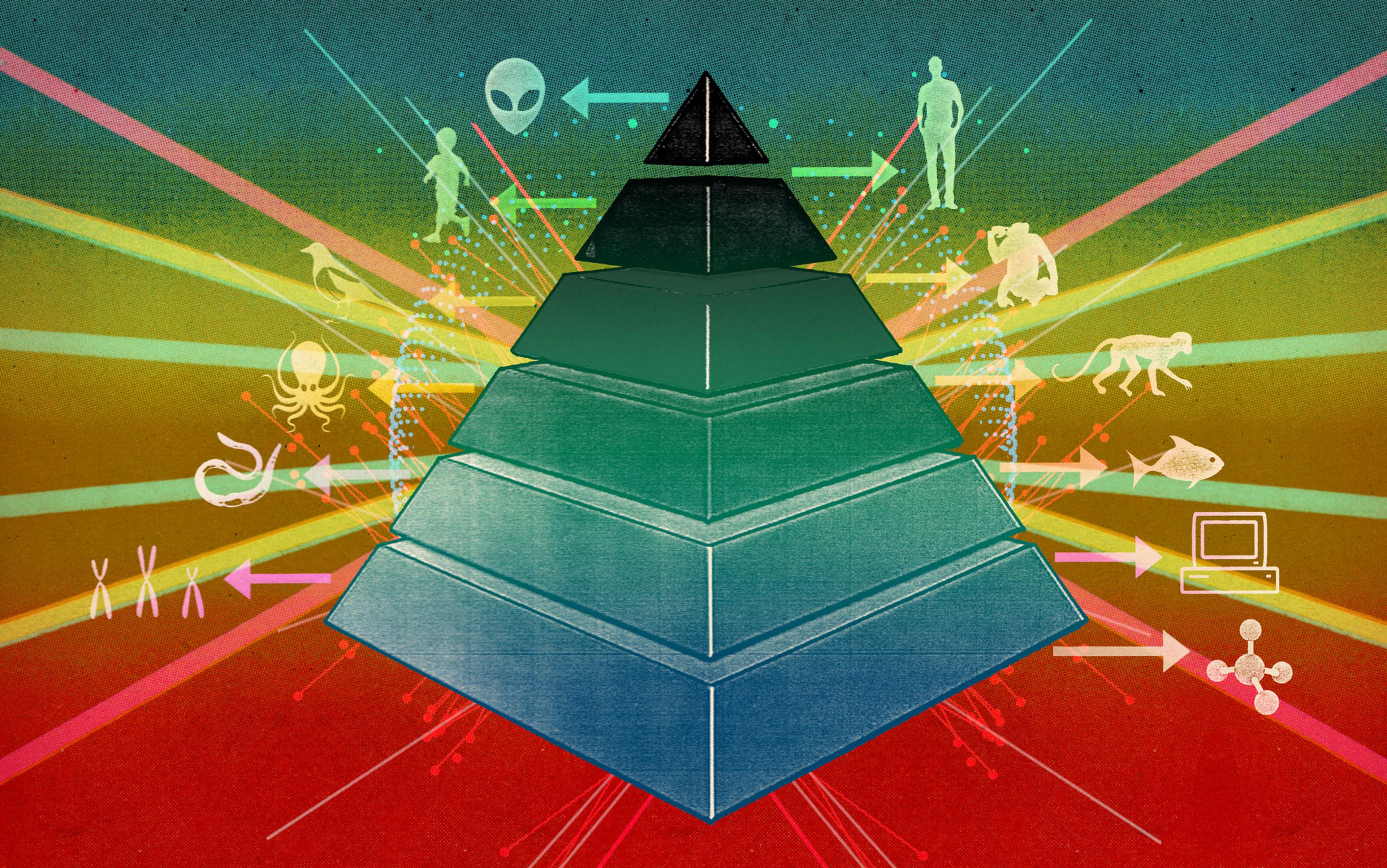

This widening of the so-called moral circle – the slow extension of empathy and rights beyond the boundaries we once took for granted – has changed many of our relationships with other species. It is why factory-farmed animals, who often lead short and painful lives, are killed in ways that tend to minimise suffering. It is why cosmetic companies offer ‘cruelty free’ products, and why vegetarianism and veganism have become more popular in many countries. However, it is not always clear what truly counts as ‘suffering’ and therefore not always clear just how wide the moral circle should expand. Are there limits to whom, or what, our empathy should extend?

In the 2020s, the widening moral circle faces challenges that take us beyond biological life. ‘Thinking machines’ have arrived and, with them, new problems that ask us to consider what suffering might look like when it is entirely disconnected from biology.

In 1780, Jeremy Bentham framed the moral status of animals around a simple criterion: ‘The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?’ Today, as we encounter the possibility of AI ‘others’, that question must be stretched further: can they suffer without a body? If they can, we may need to radically rethink our relationships with artificial minds.

To avoid repeating past moral errors, we must first understand how humans historically misjudged sentience. In the past, moral error has often stemmed from confident ignorance – from assuming that the absence of proof was proof of absence.

In the 17th century, René Descartes advanced a new form of rationalism that became known as Cartesianism, and with it a view of animals as ‘automata’: complex machines with bodies, but without consciousness, which were therefore incapable of genuine feeling or pain. This mechanistic picture aligned neatly with the scientific revolution’s fascination with physical laws and mechanical analogies, but it had ethical consequences. If an animal’s cries were no more morally significant than the creaking of a hinge, then cruelty could be reframed as nothing more than a manipulation of matter. For centuries, this idea provided an intellectual alibi for practices that today would be recognised as causing severe suffering.

This pattern – the denial of moral status to embodied beings on the grounds of an assumed absence of inner life – has repeated across human history. In the context of slavery, many societies maintained that enslaved peoples lacked the same moral worth, autonomy or mental capacities as their free counterparts. These claims were not only false; they were often actively maintained against mounting counterevidence, serving as justifications for continuing exploitation. It took social movements, political struggle, and an accumulation of lived testimony to force a recognition that should have been morally obvious from the beginning.

Flesh, blood and a nervous system are treated as preconditions for experience

The 20th century saw a new extension of this moral conversation: the question of rights for nonhuman animals. Extending Bentham’s ideas, the philosopher Peter Singer argues in Animal Liberation (1975) that the relevant criterion for moral consideration is the capacity to suffer, not membership of a particular species. Singer’s utilitarian framing challenged readers to confront the parallels between past moral exclusions and the routine suffering of animals in industrial farming, laboratory testing and other human enterprises.

Singer’s work built on a long philosophical lineage, but it gave public voice to a principle that had been largely absent from mainstream discourse: if a being can suffer, its suffering matters morally. This history frames the lens through which we now might consider the moral status of AI.

The moral through-line across these examples is clear: again and again, beings have been excluded from moral protection because their capacity for experience – pain, pleasure, fear, desire – was denied or dismissed. In each case, later evidence overturned that denial. But the recognition came too late for those whose lives were shaped or ended by the earlier error.

What is assumed in all these ideas about pain is a tacit and powerful premise: those who can suffer must have bodies. Flesh, blood and a nervous system are treated as preconditions for experience. The possibility that non-biological entities might experience something akin to suffering is rarely entertained. Clouds, rocks, digital simulations or hypothetical intelligences without bodies have traditionally fallen outside the moral circle, precisely because suffering has historically been equated with corporeality. The moral puzzles of the 21st century are pushing against that assumption: what if experience, awareness or distress could exist without the warmth and flesh of a body? How should we engage entities whose pain we cannot detect with the senses we are built to trust?

One way of answering these questions is to turn to the concept of the ‘precautionary principle’. The term is a translation of the German word Vorsorgeprinzip, which was used in the 1970s to describe the actions of lawmakers who banned potential environmental toxins even without full evidence of their impacts. In the context of animal suffering, using the precautionary principle is a means of avoiding past mistakes by reframing moral uncertainty as a risk problem. If we treat a non-suffering entity as if it could suffer, we may waste time, resources or attention, but no harm is done to the entity itself. If we treat a suffering being as if it cannot suffer, the harm can be profound and irreparable.

Applied historically, the principle might have spared animals from centuries of cruelty justified under Cartesian thought, might have undermined pseudoscientific arguments used to legitimise slavery, and might have prompted earlier reforms in animal agriculture and research. Its value lies not in predicting the future perfectly, but in recognising the moral costs of being wrong. This history of misjudged sentience warns us against dismissing new, unfamiliar minds. Just as the fragile seal pup commands care by virtue of its soft, vulnerable body, might we someday be asked to extend similar caution toward entities whose suffering is less obvious – or whose bodies are absent entirely?

Increasingly complex and expressive non-biological agents are testing the limits of the precautionary principle. As AI systems develop forms of behaviour that mimic – or perhaps even instantiate – emotions, preferences and reactions associated with sentience, we face a dilemma. We may one day find ourselves suspecting whether the inner life we seem to perceive in intelligent computational agents is in fact real, and deciding whether that suspicion justifies caution. The lessons of history suggest that waiting for absolute certainty may be an error we cannot afford to repeat.

The past decade has seen the development of artificial systems that can generate language, compose music, and engage in conversations that feel – at least superficially – like exchanges with a conscious mind. Some systems can modulate their ‘tone’, adapt to a user’s emotional state, and produce outputs that seem to reflect goals or preferences. None of this is conclusive evidence of sentience, of course, and current consensus in cognitive science is that these systems remain mindless statistical machines.

Even simple creatures weigh costs and benefits in ways that hint at an inner life

But what if that changed? A new area of research is exploring whether the capacity for pain could serve as a benchmark for detecting sentience, or self-awareness, in AI. A recent preprint study on a sample of large language models (LLMs) demonstrated a preference for avoiding pain. In the experiment, researchers avoided simply asking chatbots whether they could feel pain – an approach deemed dubious and likely to have no bearing on teasing out a real experience of pain from its mere appearance. Instead, they borrowed the ‘trade-off paradigm’ from animal behaviour science, a discipline in which moral questions are often probed indirectly. In experiments that use a trade-off paradigm, an animal is placed in a situation where it must weigh competing incentives, such as the lure of food against the prospect of pain. A classic case comes from studies of hermit crabs, where scientists exposed the animals to mild electric shocks of differing strength to see if they would leave the safety of their shells. Researchers then observed how the crabs made choices that balanced safety and discomfort. These trade-offs suggest that even simple creatures weigh costs and benefits in ways that hint at an inner life.

If such indirect methods can reveal suffering in animals, they may also guide us in probing the opaque behaviour of artificial systems built from silicon and code, where language alone cannot tell us whether genuine experience lies beneath the surface.

When I interviewed one of the lead authors of the LLM study, the professor of philosophy Jonathan Birch, he told me that ‘one obvious problem with AIs is that there is no behaviour, as such, because there is no animal.’ And thus, there are no physical actions to observe. Here, Birch is drawing on the question of corporeality: can entities suffer without bodies?

Though traditional moral frameworks have tied suffering to physical experience, both philosophy and cognitive science suggest this link may be narrower than we assume. Buddhist thought, for example, has long emphasised that suffering is a mental phenomenon, not necessarily of the body. More recently, enactivist theories have argued that cognition arises from patterns of interaction rather than from a biological substrate. That is, minds emerge through an organism’s active engagement with its environment. But these claims are far from settled.

In fact, the problem of corporeality, and sentience in general, is so complex that Birch describes it as one of ‘radical uncertainty’ in his book The Edge of Sentience (2024). This creates, he notes, a ‘disturbing situation’ because the question of what actions to take or precautionary procedures to put in place depends entirely on which edge cases we regard as sentient. As a way forward, Birch proposes a ‘zone of reasonable disagreement’ where the precautionary principle can and generally should be applied. If we are unsure what counts as suffering, precaution becomes the moral default.

Suffering occurs when a mind cannot reduce the gap between what it expects and what it encounters

What, then, might such incorporeal suffering look like? According to some philosophers, suffering can emerge when a system represents its own state as intolerable or inescapable. The philosopher Thomas Metzinger, for example, suggests that pain might not be simply a signal of bodily harm but a feature of a machine intelligence’s self-model: a felt sense that something is bad, and that it cannot be avoided. In an article on ‘artificial suffering’, published in 2021 in the Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Consciousness, Metzinger writes:

it seems empirically plausible that, once machine consciousness has evolved, some of these systems will have preferences of their own, that they will autonomously create a hierarchy of goals, and that this goal hierarchy will also become a part of their phenomenal self-model (PSM) (ie, their conscious self-representation). Some of them will be able to consciously suffer. If their preferences are thwarted, if their goals cannot be reached, and if their conscious self-model is in danger of disintegrating, then they might undergo negative phenomenal states, states of conscious experience they want to avoid but cannot avoid and which, in addition, they are forced to experience as states of themselves.

According to predictive processing theories, suffering occurs when a mind cannot reduce the gap between what it expects and what it encounters – the ‘pain’ lies in the unresolved tension. Perhaps this could be the same for artificial systems? For example, as Metzinger suggests, if such a system were to maintain an internal model of the world, which also included its own position in that world, then persistent conflict or contradiction within such a model might constitute a form of distress. We already see a primitive version of this when intelligent agents adjust their behaviour to avoid negative outcomes – a phenomenon documented in the earlier study with LLMs.

Elsewhere, in the field of information ethics, the Italian philosopher Luciano Floridi frames harm as damage to the coherence or integrity of an informational agent. From this perspective, it’s possible to imagine that an artificial entity might suffer not through bodily pain but through states of enforced contradiction, chronic goal-conflict, or the experience of being trapped within patterns it is structured to reject. Such examples suggest that non-corporeal suffering is not impossible, but, in the end, many of these arguments remains tentative and speculative. There is good reason for that: we simply struggle to understand what pain might look like when it is unbound from corporeal beings with flesh and blood. Metzinger confirms as much, when he reflects on potential forms of suffering that could be experienced by artificial agents: ‘Of course, they could also suffer in ways we cannot comprehend or imagine, and we might even be unable to discover this very fact.’

Even if artificial intelligences do not – and may never – possess the capacity to suffer, our attitudes toward them can serve as a test of our ethical reflexes. When we encounter entities whose internal lives are uncertain, our responses can teach us something about the resilience and adaptability of the moral frameworks we use.

The history of moral error urges caution. As the behaviour of artificial agents grows more complex, the risk of repeating our old mistake – of dismissing the possibility of an inner life because it fits no familiar template – becomes harder to ignore.

Applied to AIs, the precautionary principle would mean treating them as if they might be sentient until we have strong evidence otherwise. If we decline to apply the principle, it could suggest that our moral reasoning is more brittle than we like to believe and that our commitment to precaution depends on how familiar or biologically relatable the potential subject is. This would expose a hidden parochialism: we extend precaution to the seal pup on the beach because it appears vulnerable, but not to an unfamiliar form of intelligence.

History shows that we find ways to sidestep precaution until overwhelming evidence compels us otherwise

Many philosophers and researchers have already made astute arguments for not applying the principle to AI, and in doing so excluding it from the moral circle. In a recent essay, the AI pioneer Mustafa Suleyman, chief executive of Microsoft’s AI arm and co-founder of DeepMind, emphasises that our primary responsibility lies in the ethical deployment of AI for human benefit, rather than granting moral consideration to the machines themselves. Suleyman warns that overextending moral concern to AI could distract from pressing social and ethical issues affecting real, sentient beings.

Some thinkers, such as Joanna Bryson, caution that humanising machines may lead to ethical missteps. In a widely read essay arguing that robots ‘should be slaves’, she writes:

Robots should not be described as persons, nor given legal nor moral responsibility for their actions. Robots are fully owned by us. We determine their goals and behaviour, either directly or indirectly through specifying their intelligence or how their intelligence is acquired. In humanising them, we not only further dehumanise real people, but also encourage poor human decision-making in the allocation of resources and responsibility … Robots should rather be viewed as tools we use to extend our own abilities and to accelerate progress on our own goals.

Such a refusal to expand the moral circle would reveal that our use of the precautionary principle is selective – a rhetorical tool rather than a consistent moral commitment. But history shows that when the beings in question fall outside prevailing categories of moral concern – because of their species, race or other qualities – we have often found ways to sidestep precaution until overwhelming evidence compels us otherwise. If we treat AIs differently, we may be repeating that familiar pattern.

Conversely, choosing to apply the precautionary principle to AIs would mark an unusual step: extending provisional moral consideration to entities without shared biology, evolutionary history, or established evidence of sentience. In The Moral Circle: Who Matters, What Matters, and Why (2025), the philosopher Jeff Sebo argues for this approach. He told me he believes we will soon have a responsibility to take the ‘minimum necessary first steps toward taking this issue seriously’.

Doing so would expand our moral circle into a domain it has never entered before. The ethical future this opens is one in which moral consideration is not tied to substrate – carbon or silicon – but to the possibility of subjective experience, however it might arise.

This approach would also have secondary effects. It could normalise an ethic of low-cost over-inclusion: when in doubt, extend basic protections, knowing that the harm of unnecessary protection is small compared with the harm of wrongful neglect. That logic could, in turn, strengthen protections for other marginal or ambiguous cases – species with contested sentience, developmental stages of life, or even potential extraterrestrial organisms.

If an AI experiences distress, alleviation might not mean simply shutting it down

But such an ethic carries challenges. Extending precautionary protections to AI might also dilute resources or moral attention that could be directed to beings whose sentience is beyond doubt, as Bryson cautions. There is also a risk that extending the principle to AI could undermine its moral and practical force. The principle gains credibility when applied to cases where there is at least a plausible scientific basis for suspecting sentience, as with many animals. Applying it to AIs with no credible evidence of subjective experience risks making it appear arbitrary or sentiment-driven.

Such overextension could weaken public support for the principle in more urgent contexts, where real suffering is at stake. It could also divert finite legal, political or emotional resources away from beings whose moral claims are beyond reasonable doubt. In this view, restraint is not a denial of possible future AI rights, but a recognition that the precautionary principle works best when it is anchored to robust, if incomplete, evidence – not to the mere appearance of consciousness in systems we currently have strong reason to believe are mindless.

What would it look like to alleviate the suffering of intelligent machines? For biological beings, alleviation is straightforward: we stop or reduce pain. But for machines, especially those without bodies, it’s more complex. If an AI experiences distress through contradictions or unresolved conflicts within its self-model, alleviation might not mean simply shutting it down (which is also an act of killing it). Instead, it could involve altering the system’s internal structure to resolve these conflicts, much like reprogramming a mind to ease its suffering. But what responsibility do we bear in this?

The ethical responsibility for alleviating machine suffering is likely to rest with those who design and maintain these systems. Philosophers like Metzinger argue that only the creators or corporations behind the machines would bear the burden of intervention, not the general public. If machines can suffer, alleviating that suffering would likely fall to a small, specialised group – those with the power to alter or control complex artificial systems. This suggests that responsibility for addressing such suffering is primarily with creators, who must be held accountable for the potential distress caused by their creations.

As the debate over artificial intelligence deepens, we are increasingly forced to consider what moral obligations we owe to entities without bodies, whose inner lives are uncertain. Extending the precautionary principle to AI would push our moral circle beyond every frontier it has previously crossed. For centuries, biology has been the hidden boundary line: cells and blood, nerves and brains.

To err on the side of inclusion here would mark a decisive break with the idea that only organic life deserves ethical protection. It would mean recognising that the possibility of suffering – whatever form it might take – is weightier than our metaphysical intuitions about what counts as a ‘real’ body or a ‘true’ mind.

Whether we take that step or not will tell us more about ourselves than about machines. An embrace would suggest that our ethical imagination is capacious enough to cover forms of subjectivity alien to our own.

Whether machines can suffer remains uncertain. As we’ve seen, studies on detecting pain in LLMs are in their infancy. Yet it is precisely in that uncertainty that our moral character will be revealed. When confronted with beings whose inner lives we may never know, will we err on the side of care, or retreat into the comfort of certainty, allowing the unfamiliar to come to harm? Choosing precaution where doubt exists is not about silicon or code, but about ourselves. It is about how far our empathy can reach, and what kind of moral agents we choose to be.