Suppose a person is very concerned about the ethical issues around food and farming, especially animal welfare, but for whatever reason finds that a wholly plant-based diet does not work for them. What is the most defensible step away from veganism – the best compromise to make, if it is a compromise at all?

About a year ago, this question became vivid to me soon after I set out on an experiment: a near-vegan diet for a month. For some time, I have tried to eat in a way mindful of ethical issues, avoiding, albeit imperfectly, the products of inhumane factory farming. But I have eaten animal products, including meat and fish, regularly. After spending a lot of time in recent years working on questions about animal minds (initially trying to understand octopuses and other cephalopods, and then moving on from there), the ethical questions around food began to feel quite pressing. So I wanted to find out how I felt on a diet with almost no animal products.

My plan was near vegan, as I allowed myself two eggs each day, and some minor deviations (didn’t worry if I was given butter for my toast, didn’t query the details of Thai sauces, and stayed with my usual fish oil tablets). The eggs were included because, ever since another series of dietary experiments a few decades earlier, I have found that a high-protein and fairly high-fat diet is best for my general wellbeing. So, I thought, two eggs would help smooth the transition, along with protein supplements. Free-range eggs I see as the most ethical of all widely available animal products. Some vegans hold that eating eggs of any kind is unethical, while others at least see this choice as more defensible than other animal foods. (Peter Singer, in his book Animal Liberation, regards free-range egg production as acceptable.)

The aim of the experiment was to look at the possibility of heading towards veganism, and to do this primarily for animal welfare reasons. I accept some of the arguments against meat made on environmental grounds, but the issues around animal suffering are primary for me.

To my surprise, the experiment quickly became an illuminating failure. The regime was, after just a few days or so, much harder than I had expected. I felt unsettled, tired, and much of the time quite cold, surprisingly (in February in Australia). Heartburn, headaches, inattention… it did not go well. On day 10, I decided to change plans, and add some dairy products to the diet for the middle third of the month. This transition was just as surprising as the previous one. Immediately I felt fine, with all those problems out of the picture. I felt better than fine, in fact – very sharp. Ten days after that, I resumed the near-vegan regime. The results were as discouraging as before, and I switched back. By the end of the month, I’d spent half of it mostly vegan and half as a vegetarian.

Perhaps I should have stuck with the first, mostly vegan diet, and waited to get used to it. (My understanding is that one’s microbiome, one’s gut ecology, has to make a shift.) But I was reluctant to do this, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. With that unsettled feeling, day after day, I suspected I was more vulnerable to pathogens than usual. I expected to catch COVID-19 at some stage (as I did, a month or so later), and wanted to be physically well-equipped to fight it off.

I realise that this was a very short experiment. But the moments of transition between the various diets posed some choices in a clear way. Suppose one decides that a wholly plant-based or near-vegan diet is not going to work, and something must be added. If one is looking for one step away, thinking primarily about animal welfare questions, then three options appear that have completely different kinds of justification:

- humanely farmed meat (especially beef)

- wild-caught fish

- dairy products (conventionally farmed)

These aren’t really the only three options (I will look at others below), but they are some obvious and available ones, within a developed-world urban or suburban setting. Let’s say, initially, that the goal is to choose one of these as the step away. Which should it be?

I said above that they have different kinds of justifications and, when one looks closely, something like an incommensurability appears in the situation. This term from philosophy means that you can’t measure or compare alternatives using a common standard that is fair to all of them. No suitable ‘common currency’ or measuring stick is available. These three possible ways of going shopping bring on board quite different ways of looking at the moral issues.

Let’s clarify each option before looking at the ethical side. When I talk about humanely farmed beef, in option 1, I have in mind beef produced so humanely that it makes sense to think that the cows have a good life overall, and a life that is better, most likely, than the life that nearly all nonhuman mammals might have. This is not just supermarket meat labelled ‘free range’, but a smaller fraction of what is produced. This meat tends to come from specialist butchers who work with individual farms. In many cities, this is obtainable now. It tends to be expensive when compared with less humanely produced meat, and that means it won’t be a feasible choice for everyone. But where it is a live option, it’s certainly worth considering. (What about humanely farmed chickens, pigs, and so on? Yes, they are included, but each case is a bit different and I am going to focus a bit on beef.) These animals have a good life overall. On the other hand, killing is an inevitable part of this kind of farming, and perhaps there is something intractably bad in the practice of raising sentient animals to be killed.

One might instead opt for wild-caught fish (and some other wild-caught seafood) – option 2. In that case, killing is also part of the picture, but our relationship to the animals’ lives is very different from what we saw in the first option. Our role here is to cut short a life that would end anyway; we do not raise the animals to kill them. (If an animal is raised to be fished or hunted, I don’t include it here.) I think that the deaths involved in commercial fishing are probably not especially awful, compared with the deaths that would follow in the wild. But death is death, taking place at our hands, and the numbers involved are huge.

The third option is dairy. I could become one of those epicurean vegetarians who don’t eat meat but have an impressive knowledge of the endless international subtleties of cheese. Here the problems are different. I think that the lives of dairy cows within conventional farming are bad. They are probably nowhere near as bad as those of factory-farmed pigs, but worse than those of cows on humane farms who are being raised to be eaten, perhaps often worse than those of conventionally farmed beef cattle (though I am not sure, and this will depend on the details of the lives in both cases).

I would rather be reincarnated as a beef cow on a humane farm than a dairy cow in nearly any modern dairy

Why do I assume, in this option, that the dairy products are conventionally farmed? Why not assume that this choice involves special, humane farming, as seen in the beef option? When I was thinking about the choices during my experiment, dairy produced in a very humane way was not available where I live, though beef was. This is no accident. It appears to be quite difficult to bring dairy farming close to the welfare level seen in the best humane farming of beef cattle, while remaining economically feasible. I do know of one dairy farm in Australia that is exemplary in this way – How Now Dairy. This farm keeps cows and calves together, sharing the milk; there is no early separation. Some cheese is made using that milk, though it is not easy to obtain where I live. (Disclosure: I own a small number of shares in this dairy.)

It might be that this kind of humane dairy can survive and expand, in which case a dairy option might be clearly best. But, at the moment, much of the milk, cheese and butter eaten by vegetarians is produced in a way that is quite cruel. Does it make a difference to choose ‘organic’ dairy? The rules for ‘organic’ status vary from place to place (as dairy farm conditions do more generally). In some settings it probably does make a significant difference, in others less so. In addition, much cheese has traditionally contained rennet, an enzyme taken from the stomach lining of calves that have been killed, and this has made cheese a more problematic choice for vegetarians. A lot of cheese can now be made with rennet substitutes, though.

Suppose, again, that the dairy products being considered are conventionally farmed, or something close to it. When one eats this food, one is not eating the body of an animal that was killed to be eaten (as in options 1 and 2). One is instead eating something made as food by an animal that remains alive. And a cow often produces 40,000 litres of milk, or more, during its life within modern farming – that is a lot of food (for example, 4,000 kg, which is more than 4 tons, of cheddar). If we ignore waste and the like, then even if one ate half a pound of cheese every day for 50 years, one would eat the output of roughly one cow.

However, that cow’s life is usually far from a good one. Cows must be pregnant, or have recently given birth, in order to produce milk, and the result is an endless cycle of pregnancies through the cow’s rather short life, with the calves removed almost immediately. In some countries, many or most dairy cows are kept indoors for their entire lives. If reincarnated after my own death, I would rather come back as a beef cow on a humane farm than a dairy cow in nearly any modern dairy. Humane dairy with cow-and-calves together might be best of all, but I am assuming, again, that this is harder to achieve economically than humane beef farming.

As I thought about this, I had an initial sense that there ought to be a best choice between the three. I’d be willing to choose any of them if I thought it was clearly the best. When I say that, I don’t mean that I’d never lapse from such a choice, but I don’t see that as the relevant standard. It would be good to have a sense of the best goal to pursue, even if it’s pursued with some flexibility or at least unreliability. But when we look more closely at the arguments, through different avenues of reasoning any of the three might be put on top.

In support of conventional dairy: killing a sentient animal might be a unique harm, and the dairy option minimises it. Far fewer animals are involved, in comparison with the other two options. In the count of lives lost, we should also include a bit over half of the calves that a cow produces. All the males and some of the females will be killed fairly quickly. Their bodies will be put to some use, but they are seen as low-value animals. The body count for dairy will still be much lower than the other options, though.

This argument in favour of the dairy option is, in a way, a pessimistic argument. The practice is agreed to be bad, but there’s not too much of it. In contrast, the humane-beef option has a kind of positive defence. On several ethical views, this practice may be a positive good. It is familiar to note that a utilitarian might mount a defence like this, where a utilitarian is someone who counts up the totality of good and bad consequences from an action, and assesses the action purely in those terms. But it’s not just utilitarians who might be on board with this kind of beef farming. Utilitarians, controversially, do not worry about the distribution of good and bad consequences over different individuals; one person’s enjoyment, if sufficiently great, can compensate for others’ pain. In the case of humane beef farming, the defence given can be one that counts the good and bad consequences of the practice for each animal individually. Animal X does well overall, over the course of its life, and the costs and benefits to animal Y, or human consumers, need not be in the picture.

In the case of sustainable fishing, I don’t think an argument could be made that this is a positive good for the fish (unless a later death would be a lot more unpleasant). But this practice might be defended by arguing that humans, in this case, are just resuming their historic position in natural food webs. We are not, as with dairy and humane beef, instituting a new and different set of relationships between our lives and the animals’. All of the fish we kill will die one day anyway, and we did not organise, curate, or confine their lives.

If plant-based diets come to dominate, this will not be a ‘happy cow’ scenario, but a ‘no more cows’ scenario

The eating of farmed fish would not be included in a defence of seafood of this kind. The animal welfare problems associated with fish farming, at least in many forms, appear to be serious. Fish farming would not receive a defence via any of the avenues discussed in this essay. What about the farming of marine animals for which questions about suffering are either out of the picture or at least much less concerning? Cases of this do probably exist – oysters, clams, mussels – but this is a shorter list than once seemed likely. The list will probably not include shrimp, for example. On the other hand, my defence of eating wild-caught fish would also apply to wild game – (wild) venison and wild boar, for example. Some people might think those cases raise special problems, as mammals are being hunted. The numbers are also much smaller, though.

Would all wild-caught seafood have the same arguments applicable to them as apply to wild-caught fish? Not necessarily, as the handling of wild-caught marine animals can be unusually cruel in some cases, as seen in the boiling alive of lobsters and other crustaceans.

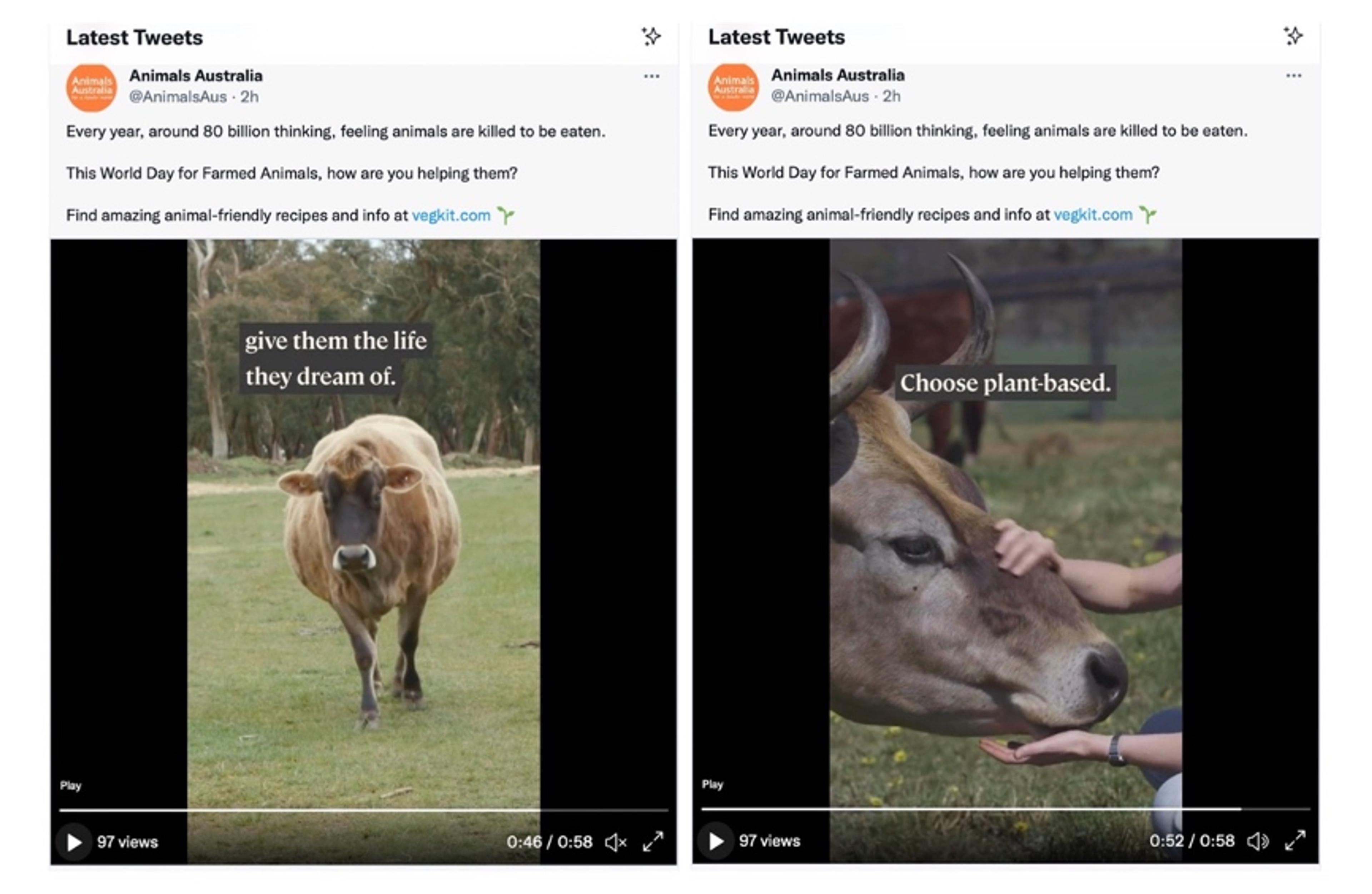

I do feel the incongruity in the claim that humane farming of any kind that includes death might be a positive good. But many views get themselves into awkward places in this area. In the picture below, I have a couple of frames from a short video that was posted on Twitter by an organisation called Animals Australia. My admiration for this organisation, I want to say at the outset, is just about boundless. For many years, they have opposed the extraordinarily cruel live export of sheep and cattle from Australia to the Middle East, and have done many other impressive things, as well. My questioning of this social media message should be read with that as background.

The suggestion in the video is that, by choosing plant-based foods, we can give cows ‘the life they dream of’ – a happy, low-stress life. But if plant-based foods come to dominate human diets, the result will not be a ‘happy cow’ scenario, but something closer to a ‘no more cows’ scenario. There will be no reason to give cows any sort of life at all, except perhaps for a few in zoos and the like (and zoos, of course, raise another set of ethical questions). If we want there to be happy cows, in any numbers, that entails a continuation of farming of some kind. This makes vivid the idea that humane beef farming might be justified as a positive good, rather than something that’s not as bad as what happens at present.

I’ve not written this essay as a dialectical exercise in which a particular conclusion is picked out in advance and I want to entice or cajole the reader into getting to the same place as me. I don’t know where the discussion leaves me. Looking at it dispassionately, the arguments for humanely farmed beef seem good, but I do share some of the unease that vegetarians have about this option. Both the other options have their advantages, and I don’t see any of them as inherently unreasonable.

One response to this situation might be: choose all of them! Spread the choices around. If one did this, everything one ate would be defensible on some line of thinking. I sympathise, though, with the rejoinder that says: make up your mind!

A recent line of thought in moral philosophy becomes relevant here. Some hold that if one is working out what to do in a situation of uncertainty about various moral arguments, one should do a kind of ‘expected value’ calculation, choosing the action that comes out best when all the moral theories that might be right are taken into account. If one is torn 50/50 between utilitarianism and a Kantian view based on rights and duties, for example, one can try to find choices that look OK on both. If one is more of a utilitarian but has some Kantian doubts, one can weight utilitarian reasons higher, but still look for something that makes some sense if the Kantian view is right. This talk of a moral theory turning out to be right, in roughly the way that the weather tomorrow will turn out one way or another, seems philosophically off base to me, but I can also see the practical appeal of this move. What would it mean in this case? Might it mean that one can indeed mix or combine the three, or does that ignore that fact that, on some of the moral outlooks that would figure in the accounting, killing sentient beings is an enormous harm?

Finally, I realise that at least some of the options I am considering here do not ‘scale up’ to yield a solution to questions about diet for humanity as a whole, especially in the long term. These reflections are intended for people right now, in situations where all three of the options discussed are feasible everyday choices, given a person’s economic situation and what is available to them. The future will probably be different, including not just advances in plant-based foods but, if the technology works out, a lot of cultured or lab-grown meat. The fact that, at some time in the future, our food choices will look very different does not change the fact that we do have these choices now. And at least for people whose constitution resists veganism, the choice is vivid. I am not left, at the end of all this, with a definite conclusion. What do you think?