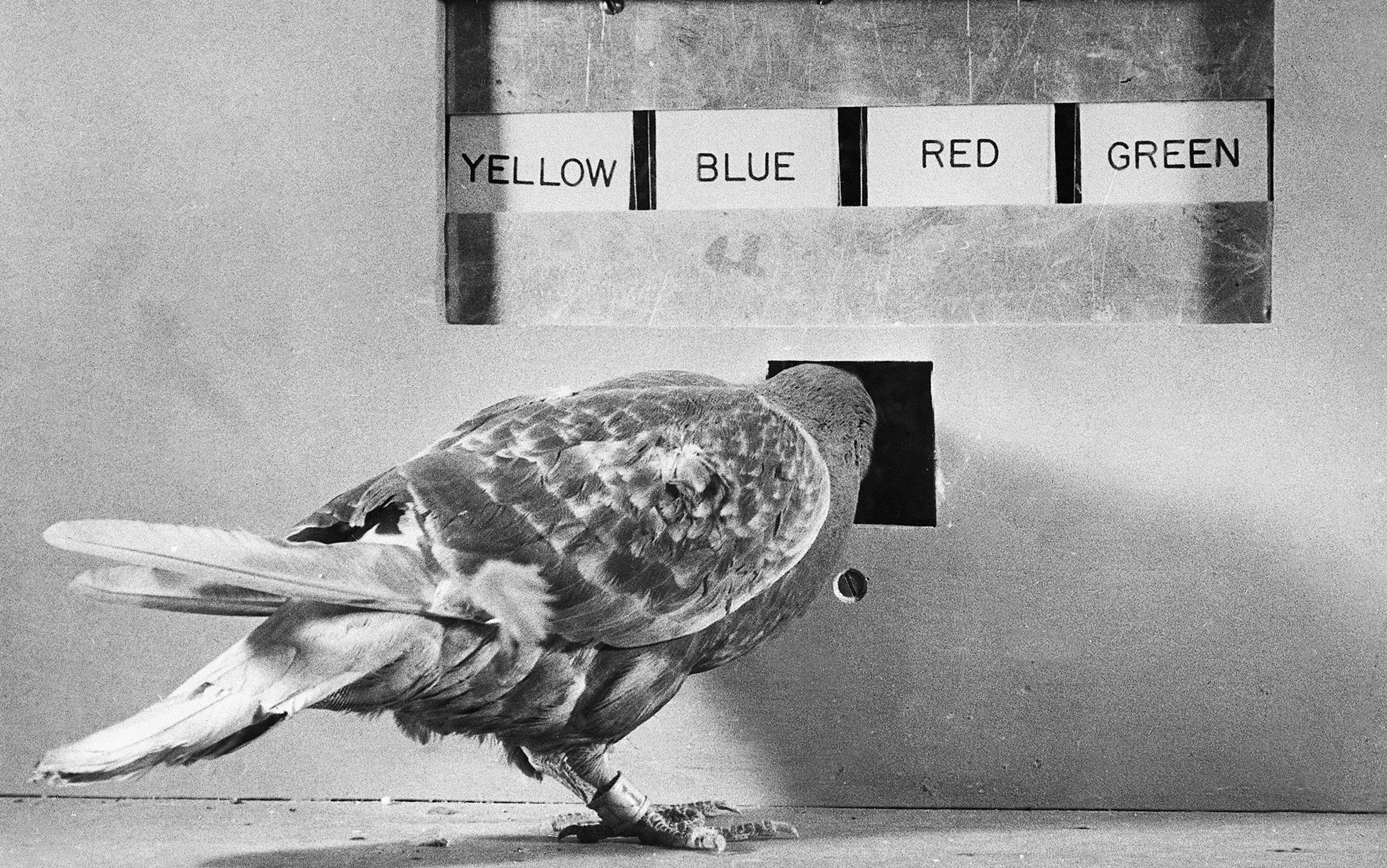

In 1796, the English physician Edward Jenner injected an eight-year-old boy in Gloucestershire with cowpox. Reasoning that absorbing a small amount of the virus would protect the child from a full-strength attack of smallpox in the future, Jenner’s bold experiment founded the practice of vaccination. Two hundred years later, the marketing industry has cottoned on to Jenner’s insight: a little bit of a disease can be a very useful thing.

If you’re one of the more than 7 million people who have watched the global fast-food chain Chipotle’s latest advertisement, you’ll have experienced this sleight of hand for yourself. The animated short film — accompanied by a smartphone game — depicts a haunting parody of corporate agribusiness: cartoon chickens inflated by robotic antibiotic arms, scarecrow workers displaced by ruthless automata. Chipotle’s logo appears only at the very end of the three-minute trailer; it is otherwise branding-free. The motivation for this big-budget exposé? ‘We’re trying to educate people about where their food comes from,’ Mark Crumpacker, chief marketing officer at Chipotle, told USA Today, but ‘millennials are sceptical of brands that perpetuate themselves’.

Never mind that Chipotle itself — with more than 1,500 outlets across the US, and an annual turnover of $278 million — is hardly treading lightly on the world’s agricultural system. The real story is that the company is using a dose of anti-Big Food sentiment to inoculate the viewer against not buying any more of its burritos. Chipotle are very happy to sell the idea that they’re on our side if it helps to keep the millennials happy. If it’s advertising we don’t like, then it’s advertising we won’t get.

In the UK, the telecommunications giant Orange creates cinema ads which are spoof scenes from well-known feature films, doctoring the scripts to include gratuitous references to cell phones. One popular instalment features the actor Jack Black recreating a scene from Gulliver’s Travels (2010), in which Gulliver is captured by the tiny Lilliputians and lashed to the ground with ropes. As the product placements for Orange become increasingly blatant, Black realises he has been tricked into acting in a cellphone ad, breaks character and begins a speech about how he won’t be duped by Orange. ‘Don’t let a mobile phone ruin your film’ runs the slogan. It’s annoying, but they know this. And they know that you know that they know. And … well you get the gist.

These ads want to be our friends — to empathise with us against the tyranny of the corporate world they inhabit. Just when we thought we’d cottoned on to subliminal advertising, personalised sidebars on web pages, advertorials and infomercials, products started echoing our contempt for them. ‘Shut up!’ we shout at the TV, and the TV gets behind the sofa and shouts along with us.

It seems almost quaint, now that popular culture is riddled with knowing, self-referential nods to itself, but the aim of advertising used to be straightforward: to associate a product in a literal and direct way with positive images of a desirable, aspirational life. How we chortle at those rosy-cheeked families that dominated commercials in the post-war era. Nowadays, we adopt the slogans and imagery as ironic home decor — wartime advertisements for coffee adorn our kitchen walls; retro Brylcreem posters are pinned above the bathroom door. But our reappropriation of artefacts from a previous era of consumerism sends a powerful message: we wouldn’t be swayed by such naked pitches today.

Genre-subverting ads started to emerge as early as 1959, when the Volkswagen Beetle’s US ‘Think Small’ campaign began poking fun at the German car’s size and idiosyncratic design. In stark contrast to traditional US car adverts, whose brightly coloured depictions of gargantuan front ends left the viewer in no doubt that bigger was better, the Beetle posters left most of the page blank, a tiny image of the car itself tucked away in a corner. These designs spoke to a generation that was becoming aware of how the media and advertising industries worked. The American journalist Vance Packard had blown the whistle on the tricks of the advertising trade in The Hidden Persuaders (1957), and younger consumers increasingly saw themselves as savvy. Selling to this demographic required not overeager direct pitches, but insouciant ‘cool’, laced with irony.

Ads for sports drinks bemoan the abundance of minutely differentiated sports drinks on the market, and beers yearn for the day when a beer was just a beer

In subsequent decades, self-aware adverts became the norm, and advertising began to satirise the very concept of itself. In 1996, Sprite launched a successful campaign with the slogan ‘Image is nothing. Thirst is everything. Obey your thirst’. In 2010, Kotex sent up the bizarre conventions of 1980s tampon adverts (happy, dancing women, jars of blue liquid being spilt) by flashing up the question ‘Why are Tampon adverts so ridiculous?’ before displaying its latest range of sanitary products.

‘Companies try to convince you that they are part of your family,’ says Tim Kasser, professor of psychology and an expert on consumer culture at Knox College in Illinois. ‘They want to create a sense of connection or even intimacy between the viewer and the advertiser. An ad that says: “Yes, I know you know that I’m an ad, and I know that you know that I’m annoying you” is a statement of empathy, and thus a statement of connection. And as any salesperson will tell you, connection is key to the sales.’

This technique of cultivating empathy through shared cynicism has taken off over the past decade. Today, ads for sports drinks bemoan the abundance of minutely differentiated sports drinks on the market, and beers yearn for the day when a beer was just a beer. The Swedish brewery Kopparberg has done more than any other company to promote the idea that cider can come in many delicious fruity flavours, so if anyone is to blame for the difficulty in buying plain old apple cider, it is Kopparberg. Yet their most recent invention is ‘Naked’ apple cider. As the company’s UK managing director Davin Nugent told The Morning Advertiser:

Innovation through fruit is not enough. The bigger picture is apple cider and we’re opening the back gate into the category. The apple taste in cider has been lost and become bland… we’re on to something exciting.

Corporate advertising is the ultimate shape-shifter; the perpetual tease. No sooner had the virulently anti-capitalist ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement begun than the American rapper Jay Z’s clothing label created and marketed an ‘Occupy All Streets’ spin-off T-shirt. But as citizen cynicism has advanced, the space in which advertising can operate without tripping on its own rhetoric has become ever more restricted, and ever more bizarre.

Feeling jaded and cynical about samey scripts in ads? Commercials such as 2012’s Old Milwaukee Super Bowl spoof, in which Will Ferrell’s formulaic endorsement gets cut off mid-sentence, might still speak to you. Getting a vicarious thrill from viral videos? Ads can mimic that excitement, with carefully coordinated campaigns to capture the grassroots feel, such as the ‘amateur footage’ of a man hacking the video screens in Times Square, New York, in fact promoting the film Limitless (2011). Cynical about the lack of spontaneity in advertising messages? ‘Real-time’ news-led marketing can make even the most hackneyed of products seem cutting-edge — although American Apparel’s attempt in October last year to launch the #SandySale off the back of the worst Hurricane to hit New York in living memory was not the blast they had hoped for.

The ambiguous, semi-disguised adverts of today would appear to be the commercials we deserve: self-cynical sales pitches for a jaded generation

At the same time, Magazine content, musical and theatrical entertainment and, in particular, online media are often entirely integrated with the commercial messages that bankrolled them. This probably wouldn’t have been possible if advertisers had not made the strategic move from the blatant salesmanship of yore to the subtler, more oblique arts of modern industry. As consumers cottoned on to the tricks of the trade, ads have stayed one step ahead.

There have, of course, been attempts to kick back. An entire lexicon has flourished around the idea of subverting the advertising industry — from acts of ‘brandalism’, which distort or undermine corporate iconography, to ‘culture jamming’ (satirical analyses of the business world). Adbusters, the long-running Canadian magazine, has dedicated itself to exposing and challenging the the corporate world generally, not just advertising. But a 2011 report for the Public Interest Research Centre about the cultural impact of commercial messages argued that:

The public debate about advertising — such as it exists — has also been curiously unfocused and sporadic. Civil society organisations have almost always used the products advertised as their point of departure — attacking the advertising of a harmful product like tobacco, or alcohol, for instance — rather than developing a deeper critical appraisal of advertising in the round.

So what would a deeper look tell us? Perhaps it is that the ‘cynical distance’ inherent in knowing, self-immolating, empathetic adverts not only perpetuates brands, but is at the foundation of advertising itself. By ‘factoring in’ dissent, the ad neutralises it in advance, like the stock market inoculating itself against future shocks by including their likelihood in share prices. The advertising industry anticipates and then absorbs its own opposition, like a politician cracking jokes at his own expense to disarm a hostile media.

And the industry’s seemingly endless capacity to perpetuate itself matters. Marketing is not simply a mirror of our prevailing aspirations. It systematically promotes and presents a specific cluster of values that undermine pro-social and pro-environmental attitudes and behaviour. In other words, the more that we’re encouraged to obsess about the latest phone upgrade, the less likely we are to concern ourselves with society’s more pressing problems. That’s a reason to want to keep a careful tab on advertising’s elusive and ephemeral forms.

Encouragingly, there is some evidence that young people are quietly developing their own defence mechanisms — the ‘click-through’ rate for online advertising has plummeted from a heady 78 per cent for the world’s first banner ad in 1994 to a meagre 0.05 per cent for Facebook ads in 2011.

The Beetle adverts at the tail end of the 1950s picked up on the growing media smarts of the post-war generation, and Sprite’s ironic critique of image-led branding could almost have been lifted from the arguments of the 1990s anti-globalisation movement. The ambiguous, semi-disguised adverts of today would then appear to be the commercials we deserve: self-cynical sales pitches for a jaded generation. Instead of questioning the economic mechanisms that lead to the homogenisation of town centres, we shop and drink coffee in commercial spaces disguised in the stylishly-frayed aesthetics of the counter-culture.

Satire has long been acknowledged as a paradoxical crutch for a society’s existing power structures: we laugh at political jibes, and that same laughter displaces the desire for change. As such as Chipotle’s — which express our concerns about the failings of globalisation in a safe space before packing them away — are surely an equivalent safety valve for any subversive rumblings. We all like to think that we’re above the dark art of advertising; that we are immune to its persuasive powers. But the reality is that, though we might have been immunised, it is not against ads: it is against dissent.