In her first year teaching at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, Leann Pace taught a class called Near Eastern Archaeology. Thirty years ago, the course would probably have been called ‘Biblical Archaeology’, as it focuses on regions important in the birth of the major Western religions. One day, a student raised her hand and asked: ‘Why do we care about the origins of this small group of people anyway?’

Pace told me she was shocked. ‘It was one of those moments when a student wrings you to the core,’ she said. She expected students to ask challenging questions. She expected students to feel like the class was undermining their faith, or favouring one religion over another. She was not prepared for students who didn’t understand why anyone would focus on the region at all.

Religious literacy in the United States is declining. A recent study by the Pew Research Center asked Americans 32 questions about religion, and on average respondents got only half of them right. Another Pew poll has found that the percentage of people who attend weekly religious services is steadily, if slowly, decreasing.

Archaeology is the study of the past through the analysis of physical remains – but that’s only the technical definition. Archaeology is also about the present. Where scientists go, what they dig up, what they keep, and how they interpret are all inextricably linked with their own ideas about the world. When archaeologists dig up religious sites, the spirituality of the researcher can influence his or her approach to the work.

Today, many students no longer take for granted the importance of Biblical sites. Some aren’t interested in the Bible at all. And while it’s a relief that students are no longer entering the field to ‘prove’ any individual religious text, the decline in religious literacy might have drawbacks. Pace is beginning to wonder how that decline might shape the future of archaeology.

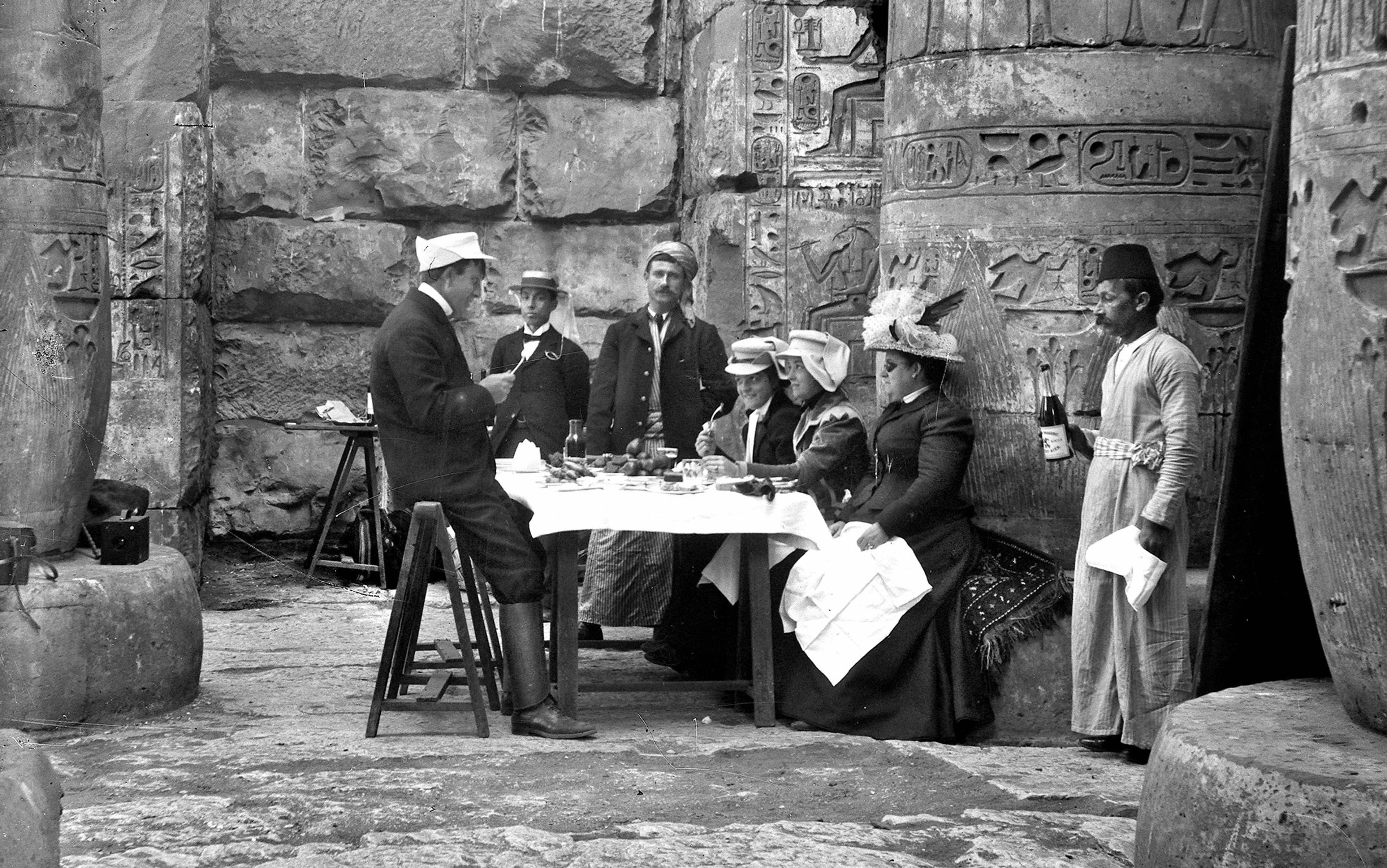

The history of archaeology is a history of writing history. Kings started looking into their past to reclaim former glories, and rebuild past monuments. The neo-Babylonian emperor Nabonidus, who ruled from 556 to 539BC, excavated old temples and rebuilt them. Historically, artefacts from far-flung places showed the reach of a kingdom, much as the Elgin marbles demonstrated the glory of the British Empire. Archaeologists also have a long history of trying to prove the validity of religious texts. In the mid 19th century, a French customs officer named Jacques Boucher de Perthes called a set of extinct animal bones ‘antediluvian’ or ‘before the flood’, arguing that they were clear evidence of human life on Earth more than 6,000 years ago.

Western archaeologists interested in vindicating religion have taken a special shine to the Middle East. In 1865, the Palestine Exploration Fund was founded with £300 and a mission to excavate the region now called the Levant, an area composed of Cyprus, Israel, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Israel and surrounding countries. At its first meeting of the group, the archbishop of York assured those in attendance that it was not a religious group. ‘Our object is strictly an inductive inquiry,’ he said. ‘We are about to apply the rules of science, which are so well understood by us in our branches, to an investigation into the facts concerning the Holy Land.’ The archbishop then continued, ‘No country should be of so much interest to us as that in which the documents of our Faith were written, and the momentous events they describe enacted.’

The Palestine Exploration Fund is still active today, but archaeology in the region has changed considerably in tone and scope. It has also undergone several name changes in the past 50 years, each an attempt to distance the field from overt spirituality. What was once called Biblical Archaeology now goes by such names as Syro-Palestinian Archaeology, Holy Land Archaeology and Archaeology of the Southern Levant.

These names matter, and they reflect the kind of work archaeologists do. When the field was called Biblical Archaeology, digs were, often unabashedly, attempts to prove the Bible. Digs were explicitly guided by questions about where the apostle Paul stood, or where the great flood of Noah began, or where the Tower of Babel might have been built. Those questions dictated not just where archaeologists dug, but also how. ‘An Islamic-period strata at a site wouldn’t be dug scientifically because people were interested in getting to a Christian or Jewish layer,’ said Pace. ‘The people digging weren’t interested in Islam.’

That prejudice was reflected in funding as well, said Laura Nasrallah, an archaeologist and New Testament scholar at Harvard’s Divinity School. ‘One of the things people used to do in the 20th century is say ‘this site is important Biblically’, to try to gain funding from people who are interested in the Bible.’ Now, Nasrallah said, that’s less common, as government funding agencies have become a major source of money – but connecting a site with the Bible can still help to support a dig, by attracting tourist dollars. In Corinth, for example, one group is rebuilding a platform, or bema, that Paul once stood on. Except that Paul never wrote of the bema specifically, and Nasrallah is sceptical of how scientifically rigorous the project really is.

In many ways the argument over who can and should be able to study the site has become a proxy for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

Since the 1960s, the field has been struggling to reconcile its interest in religion with its interest in doing unbiased science. ‘What we don’t want is the Bible dictating archaeology,’ Pace said, ‘but we can still ask questions about the ideas we see reflected in it. The question is, how do we do that responsibly so we don’t go out and treasure hunt for a Biblical site?’

In some places, these battles are still being fought. At the top of the Old City of Jerusalem sits the Haram al-Sharif, also known as the Temple Mount – one of the most sacred sites in the Middle East to both Jews and Muslims. The Jewish tradition holds that the Temple Mount is the resting place chosen by God for the Divine Presence. Muslims consider it one of the holiest sites in all of Islam, and the place where Muhammad ascended to heaven.

Currently the site is managed by an Islamic trust called the Waqf, and archaeology has been severely limited at the site. The Waqf say that the site is too sacred, and fear archaeological investigation might destroy the building. Jewish archaeologists, however, have accused the Waqf of doing damage to the site themselves and purposely destroying archaeological evidence. In many ways the argument over who can and should be able to study the site has become a proxy for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Pace said.

While spots like the Temple Mount might always be hotly, religiously contested, today fewer archaeologists seem to be driven by religious passion. And that might be a good thing, said Pace. ‘I’m hopeful that maybe as the field broadens and we get more people of varying religious background or no religious background, people who are little less connected to the sacred texts, that the discipline will open up and we’ll have some new ideas,’ she said. Being too close to a religion can bias you, but being too far from it means you can’t understand the significance of certain artefacts.

It was being too close to a bias that doomed Beirut. Beirut is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, and over the millennia it has endured countless spasms of violence. But in 1994 the destruction of its archaeological history began. It wasn’t war that wrecked the mosaics, the columns, the monuments. It wasn’t militants or ISIS who dumped truck after truck full of Beirut’s history into the Mediterranean Sea. It was renovation. ‘The largest urban redevelopment project of the 1990s’, as it was later described.

Albert Naccache, an archaeologist, told me he tried to stop the construction. In an article in Archaeology Magazine from 1996 he describes the meetings and calls he made to historians, politicians and fellow archaeologists. But nothing worked. A parking lot that could hold 2,700 cars was dug out, as bulldozers cut through souks that Naccache said had been inhabited for 26 centuries. ‘They sent in bulldozers without any supervision or anything and dumped into the sea a Bronze Age palace, tombs, all this was thrown to the sea without any excavation.’

The idea that the Phoenicians and the Arabs were two distinct peoples persisted, partly due to religious bias

Naccache said that the excavators had been reluctant to allow archaeological assessment before the dig, in part because it would slow them down, but that there was more going on too. ‘Beirut was destroyed not only because there was a company that wanted to build without taking into consideration any archaeologists, but because archaeologists played the game.’ The game, Naccache said, was one of history and politics more than one of science. ‘They were afraid of finding something that would be Phoenician, and not Arab.’

When French archaeologists first started digging in Lebanon and the surrounding areas, they described two distinct peoples, the Arab Muslims and the Canaanite Phoenicians. But Naccache said that, until it was ‘discovered’ by those archaeologists, that distinction never existed. ‘They shared in the culture, but they all belonged to one kingdom centred in a city.’ The so-called Phoenician text is very similar to Arabic, as is the spoken language. Nonetheless, the idea that the Phoenicians and the Arabs were two distinct peoples persisted, partly due to religious bias. Some Christians didn’t want to be seen as Arabs, because to them Arabs were Muslim. ‘The perception, due to the work of European archaeologists, had split those people.’

Once created, that split continued. Lebanon has swung back and forth: sometimes the Phoenician identity reigns; at others, the Arab identity. In 1994, it was the Arab identity that was on top, which is why, Naccache argues, nobody wanted to dig in the rubble created by the renovations. If they found what seemed like Phoenician ruins, it would shake the hold of the Arab narrative. And if they removed all that history, nobody could question Beirut’s true story. Naccache calls this phenomenon the ‘memorycide’ of Beirut. He calls Beirut – a city that has been reborn over and over again over thousands of years – ‘the lobotomised phoenix’. He said that this is how it always goes with archaeology. ‘The main aim of archaeology is to write history, not to find monuments.’

The whole thing was so upsetting that Naccache actually left archaeology entirely. ‘I was very depressed for many years,’ he said, ‘so I changed fields. I’m working on human evolution and language evolution.’ Even today he is doubtful that archaeology is seeking objective answers. ‘The idea that now we are coming out being more enlightened and coming out of religious impact and being able to look at the archaeology and history in a more objective way seems very strange to me. I don’t believe it at all, unfortunately.’

But it’s not always about being too close to your work, your identity too tied up in what you find in the ground. Archaeologists in the Americas have often blundered when they had too much cultural distance from the religions whose artefacts they were studying. ‘One of the big issues that archaeologists who work in the Americas have been grappling with over the last few decades is trying to take Native American religions seriously,’ said Mary Weismantel, a cultural anthropologist at Northwestern University in Illinois. In many cases, Weismantel said, archaeologists in the Americas are encountering religions they hadn’t realised were still alive. ‘People talk about the Mayans as if they’re extinct,’ she said. The modern Mayan population numbers about seven million.

Nick Tipon, the Vice-Chairman of the Sacred Sites Protection Committee of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, knows this phenomenon only too well. He recalls a time when he entered a little historical centre in Sausalito, California. Inside was a small display of artefacts from his tribe, the Miwok. On the little card next to the items it read: ‘The Miwok are extinct.’ That stung, Tipon said. ‘I don’t go out and hunt deer anymore; I drive a car. We’ve adapted to the culture that’s here but that doesn’t mean that my history, my soul is not part of that ancient culture.’

That attitude isn’t just demoralising for people like Tipon. It also detracts from the quality of the archaeology. Suntayea Steinruck, the Tribal Historic Preservation Officer of the Smith River Band of Tolowa Indian Tribe, recalls attending a talk by an archaeologist who proposed a theory about where a certain tribe had stored their grain. Steinruck raised her hand and asked if the researcher had asked a native person. He hadn’t. She jokes that it’s a bit like the Little Mermaid naming a spoon a dinglehopper. ‘Why wouldn’t you just go ask the humans, instead of the seagull?’ she said. ‘Not that I’m saying archaeologists are like seagulls, although they do say “mine” a lot.’

Unlike many Western religions, where the recruitment of outsiders is encouraged and rewarded, Native Americans are not evangelical. In fact, many tribes can be quite secretive. ‘There are a lot of things that relate to our spirituality and religion and what’s sacred, that we are not supposed to divulge to outsiders,’ said Tipon. There is no Bible equivalent – published for the masses to read and understand. Archaeologists who come on to Native American land to do work are not expected to know about the tribe’s religion, nor should they expect to be taught it. Instead, tribes ask that native people be on site to advise the archaeologists what they should and shouldn’t move or analyse.

Stones and feathers and sticks might be spiritual relics. Or they might be the leftovers from a meal

What archaeologists see as data collection, tribes see as a continuous attempt to rewrite and conquer their identity and religion – from how long ago they arrived on the land to what they used certain objects for, to where they stored their grain. ‘This is a living community, and it’s not the place of the archaeologist to tell the tribe what their history is,’ said Michael Newland, a staff archaeologist at Sonoma State University who has worked with tribes for years.

That’s a perspective that’s becoming more and more common, said Newland, as archaeologists are learning more about the living Native American religions. Tipon and Steinruck both say that newer generations of archaeologists are far better than the old guard, and that they approach each relationship on a case-by-case basis. ‘There’s hope,’ Tipon said, ‘but there’s also this old guard, and tribes are kind of waiting to see them retire.’

It’s impossible to do archaeology objectively. Even determining what constitutes a sacred object is difficult. There’s a joke among archaeologists that items labeled ‘spiritual objects’ might as well be labeled ‘we have no idea what this is’. Stones and feathers and sticks might be spiritual relics. Or they might be the leftovers from a meal. Which interpretation is picked often depends as much on the evidence as it does on the archaeologist’s own background.

As religious literacy declines, our appetite for stories seems to remain. In 2009 the History Channel started a series called The Bible Unearthed, a documentary series following archaeologists working on Biblical sites. Last year it aired a 10-hour ‘docudrama’ made up of Biblical stories. Earlier this year the Bible appeared again, in a series called Bible Secrets Revealed. This stream of books and shows and ‘docudramas’ includes not just the Bible, but the ancient Maya, Islam and Native Americans.

Out in the field, much of the overt Bible-hunting has stopped, but the religious fervour that can fuel it is still very much there, and crops up in other ways. ‘Every Lent there’s some find about Jesus that emerges,’ Nasrallah said, ‘and it’s often bad archaeology or some misunderstanding.’ People are still hungry for information that proves or disproves the Bible, even if that’s the wrong way to look at it. ‘It’s a category error to read biblical stories and to think that they’re trying to assert a newspaper-style report of something that happened,’ she said. ‘It’s not that we can’t learn something from the Bible, but those texts weren’t produced to report in that way.’

For archaeologists this can be frustrating. ‘Stuff on the History Channel annoys me, but I understand the appeal of it,’ said Pace. She placed the onus on archaeologists to fix that: ‘If we don’t like the way the stories we want to tell are being told on the History Channel, then we need to find better ways to tell them. Until we do that I don’t feel like I can complain.’ Indeed, it’s possible that these shows are what attracts new generations to archaeology in the first place. ‘I don’t blame anybody for wanting to connect to these things, and wanting to find out more,’ she said. ‘That’s why I still have a job.’