Around 50,000 years ago, our species began migrating from Africa into Europe and Asia. We were not alone. As we journeyed, we came into contact with other large-brained hominids, including our closest extinct relatives, the Neanderthals and Denisovans. For most of our history, we were part of a wider family of animals that looked and behaved like us. But by the end of the Pleistocene, around 11,700 years ago, only Homo sapiens remained.

At that moment, humans became a unique species. And that uniqueness was slowly reinforced as lines were drawn between us and every other creature. Over time, these lines hardened into barriers. We came to believe that humans were the only animals with intentionality and foresight – special skills that allowed us to produce art, architecture and agriculture. We told ourselves stories that celebrated our superiority, and even those stories themselves became examples of what set us apart: culture.

But how did culture begin? We have stories for that too. In one well-known myth, as set down by Plato in the 4th century BCE, the gods charged two Titans, Epimetheus and Prometheus, with the task of fashioning mortal creatures from earth and fire and equipping them with the qualities they would need to survive. Epimetheus began doling out strength and speed; the capacities to fly, swim or burrow; shells, warm fur, thick skin, hooves, claws and other qualities. However, when it was time to bestow a gift to humans, the Titan realised he had nothing left to give. His brother, Prometheus, not knowing what else to do, stole fire from the god Hephaestus and gave it to humans, along with the knowledge essential for their survival – gifts for which he was eternally punished.

In this fantastical tale, fire is a shorthand for culture. Its use separates humans from the ‘brute animals’ whose lives are limited to their instinctive uses of the qualities given to them by Epimetheus. Through Prometheus, humans became elevated above the beavers, bison, bears and other creatures.

More than 2,000 years later, the American author Terry Bisson wrote a different kind of myth: a short story called ‘Bears Discover Fire’ (1990). In this tale, news outlets report that bears across the midwestern and southern United States are making fires. Instead of hibernating, they plan to spend the winter keeping their fires going along the medians of interstate highways. Scientists propose that warming winters have changed the bears’ hibernation cycles, a shift that has allowed them to remember things from year to year, including the fact that they had made their discovery centuries ago. When the narrator eventually sits with the bears around their fire, he notices that they do a pretty good job of tending it, but haven’t quite figured out the right kinds of wood to burn. ‘It looked like only a few of the bears knew how to use fire, and were carrying the others along,’ writes Bisson. ‘But isn’t that how it is with everything?’

Bisson’s alternative version of the Promethean tale was first published in a science-fiction and fantasy magazine. It’s ‘fantastic’ because it seems so unlikely: surely it’s humans, and humans alone, who wield fire and culture?

In the few decades since Bisson’s story was published, our understanding of human exceptionalism has been coming apart. In the archaeological record, the line between what has traditionally been considered human culture and animal instinct is blurring in ways that challenge our conceptions of culture and history. Far from the stuff of myth or science fiction, archaeological evidence suggests that some of our human ancestors were prompted to make art by engaging with the marks left behind by other species (by bears, in fact). Early humans may also have been inspired to build wooden structures by observing beaver dams, and learned to cultivate certain plant species by paying attention to the seeds that grew along bison trails. In other words: art, architecture and agriculture are not (only) human.

Prometheus had nothing to do with it. Did animals show us how to be human?

Exploring that question involves reconsidering not just archaeological evidence but the discipline of archaeology itself. As opposed to anthropology, which studies anthropos (the ‘human’), archaeology, by definition, is not limited to our species alone: the Greek archaios means ‘ancient’ and logia means ‘science’ or ‘study of’. Yet most archaeologists (and the Oxford English Dictionary) will tell you that the discipline involves the study of past people, often through the systematic excavation and analysis of anything that falls under the wide umbrella of ‘material culture’.

How does culture become material? Although there are probably as many definitions of culture as there are examples of it, most describe culture as something that is learned rather than inherited. These cultural traits are passed on from one generation to the next not through genes, but by observing and copying established skills. Processes of cultural transmission involve imitation and innovation, practice and progress – and these all leave traces in the ground. Those traces can take a remarkable variety of forms, from shards of broken pottery to ancient dental calculus (calcified plaque) on buried teeth.

Pottery, for example, can tell archaeologists how people learned to transform malleable clay into fire-hardened ceramics through apprenticeship and experimentation. It can tell us about feasts and gift-giving practices, and may even reveal something about old stories and myths. Calcified dental plaque on teeth can trap and preserve microscopic remains of food debris and microbes, which archaeologists can use to learn about diet, health, diseases, the environment, and perhaps even the cultural or ethnic affinities of past people.

What if some of the cultural making and doing that we consider to be uniquely human was being done by animals first?

Sometimes, human material culture involves traces of other animals, too. Zooarchaeologists like me are trained to identify the remains of other species from archaeological sites by analysing bones, teeth and shells. We use these remains to gain insight into what people in the past ate and how they hunted. We learn where and when wild species were tamed or domesticated, and how animals’ bodies were used as resources, whether for tools and adornments or as potent symbols in human societies. We are not, generally, interested in the histories of the animals themselves, but rather how animals have intersected with human histories. We certainly don’t ask what kinds of things bears may have discovered and forgotten centuries ago. To put it simply: zooarchaeology is the study of animals as material culture, not an archaeology of animals and their material culture.

This is based on a well-established belief: humans make and do things because only we have culture, and when those things we make and do change over time, we call it history. When animals make and do things, we call it instinct, not culture. When the things they make and do change over time, we call it evolution, not history. Anthropologists have pointed out that this is an unusual way of thinking: at what point did we stop merely evolving from our long line of hominid ancestors, cross an irreversible threshold from nature to culture, and kickstart history?

The unique trajectory afforded to humans compared with all other animals is evident in paleoanthropologists’ use of the phrase ‘anatomically modern humans’. This terminology tries to make sense of the fact that there were members of our species hundreds of thousands of years ago who had the same morphological characteristics and physical capacities that we have today, but who seemingly had not yet taken the step into a new world of culture. By contrast, as the British anthropologist Tim Ingold argues, we never speak of ‘anatomically modern chimpanzees’ or ‘anatomically modern elephants’ because the assumption is that those species have remained entirely unchanged in their behaviours since they first took on the physical forms we see today. The difference, we assume, is that they have no culture.

But what if archaeologists and zooarchaeologists found traces that told a different story? What if some of the cultural making and doing that we consider to be uniquely human was being done by animals first?

Vertical bear-claw marks and human engravings dating back about 30,000 years in the Cussac cave at Le Buisson-de-Cadouin, Dordogne, southwestern France. Photo by Christophe Archambault/AFP/Getty Images

Consider art. Think of the way that mark-making incites more mark-making: in cities, graffiti clusters together in layers of symbols; at archaeological sites around the world, ancient rock-cut drawings are surrounded by carvings left by centuries of visitors. And deep inside caves across Europe, some of the earliest evidence of human paintings and engravings made by our ancestors and their relatives – dating back 65,000 years or more – echoes marks left by other animals.

Many millennia before spectacular figures of horses, mammoths, lions and other animals were painted (c17,000 years ago) on the walls of the famous Lascaux cave in the Dordogne region of southwestern France, hominin artists were dragging their fingers through soft clay, pecking and scratching simple lines and circles into rock, and rubbing and dotting cave walls with red ochre. These early marks were often placed around or atop the polished surfaces and claw marks left behind by cave bears, felines and other mammals. Sometimes the human marks imitate the forms of existing scratches or smoothing made by other species. Human art, then, is part of a broader tradition of animal mark-making.

At times, this ‘parietal art’ (the name for human-made art on cave or rock walls) is so similar to animal traces that archaeologists struggle to disentangle and distinguish one from the other. In the 1960s, for example, the French prehistorian Amédée Lemozi interpreted a series of engraved lines at Pech-Merle cave in the Occitania region of southern France as a representation of a masked and wounded shaman. Lemozi saw lines piercing the figure of the shaman and pecking intended to represent wounds, leading him to suggest that the shaman was depicted undergoing a ritual death. Lemozi’s ideas were taken up by the Belgian prehistorian Lya Dams in the mid-1980s and extended into a broader exploration of wounded men in Palaeolithic art. A few years later, however, the French prehistorian Michel Lorblanchet showed that the many crisscrossing lines making up the ‘wounded shaman’ on the calcite surface of the cave were, in fact, gashes in multiple directions left by the claws of cave bears.

Nonhuman carvings laid the literal and figurative foundations for human art

An engraving from Bara-Bahau cave in Dordogne, once called the oldest work of art, was reappraised as ‘almost certainly a cave bear mark’ by the Australian prehistorian Robert G Bednarik in the early 1990s. A decade later, in the cave of Les Battuts in Tarn, France, the French prehistorians Edmée Ladier and Anne-Catherine Welté and the speleologist Jacques Sabatier believed they had found distinctive human-made ‘tectiform’ signs (‘roof-shaped’ geometric designs thought to represent structures or dwellings). But they soon realised the marks were overlapping striations made by cave bear claws. Such claw marks are the best-studied type of animal markings in caves, but many other species are known to leave potentially confusing traces with their claws and horns. Bednarik, who has spent decades dedicated to the work of distinguishing between different markings through his Parietal Markings Project, suggests that the most numerous animal markings in caves are likely those created by bats. As Lorblanchet and the British prehistorian Paul Bahn wrote in their book The First Artists: In Search of the World’s Oldest Art (2017), the issue of clearly differentiating between human and animal behaviour on cave walls ‘is a fundamental problem in the birth of art’.

Since the early 20th century, some researchers interested in the origins of art – such as the archaeologists Henri Breuil and André Leroi-Gourhan, the art historian Ernst Gombrich, and the philosopher Georges-Henri Luquet – have argued that the development of figurative art was, to a certain extent, accidental. According to their theories, humans progressively realised that the marks they made unintentionally resembled elements of the world around them. Such marks might appear in the process of scratching on bone or stone during butchery and tool-making, or accidentally brushing pigment against the walls of narrow cave spaces. Those accidental discoveries allegedly opened the door to the intentional production of images that resemble things. Yet, even where marks can be differentiated between those made by animals and humans, separating ideas from instincts, or inspiration from imitation, is complicated.

In several caves in France, such as Bara-Bahau, Baume-Latrone and Margot, human-made finger flutings or ‘meanders’ follow earlier cave bear scratches. Some of these long lines of finger-combed grooves are superimposed directly over claw marks. Others are located near the bear-made traces, echoing their orientation. In Aldène cave in the south of France, human artists ‘completed’ earlier animal markings. More than 35,000 years ago, a single engraved line added above the gouges left by a cave bear created the outline of a mammoth from trunk to tail – the claw marks were used to suggest a shaggy coat and limbs. In Pech-Merle, the same cave where Lemozi mistook cave bear claw marks as human carvings of a wounded shaman, a niche within a narrow crawlway is marked by four cave bear claw marks. These marks are associated with five human handprints, rubbed in red ochre, that date to the Gravettian period, about 30,000 years ago. For Lorblanchet and Bahn, the association between the traces of cave bear paws and human hands is no accident: ‘It is remarkable (and the Gravettians doubtless noticed it),’ they wrote, ‘that a rubbed adult hand, with fingers slightly apart, leaves a trace identical in size to that of an adult cave bear clawmark.’

Nonhuman carvings laid the literal and figurative foundations for human art.

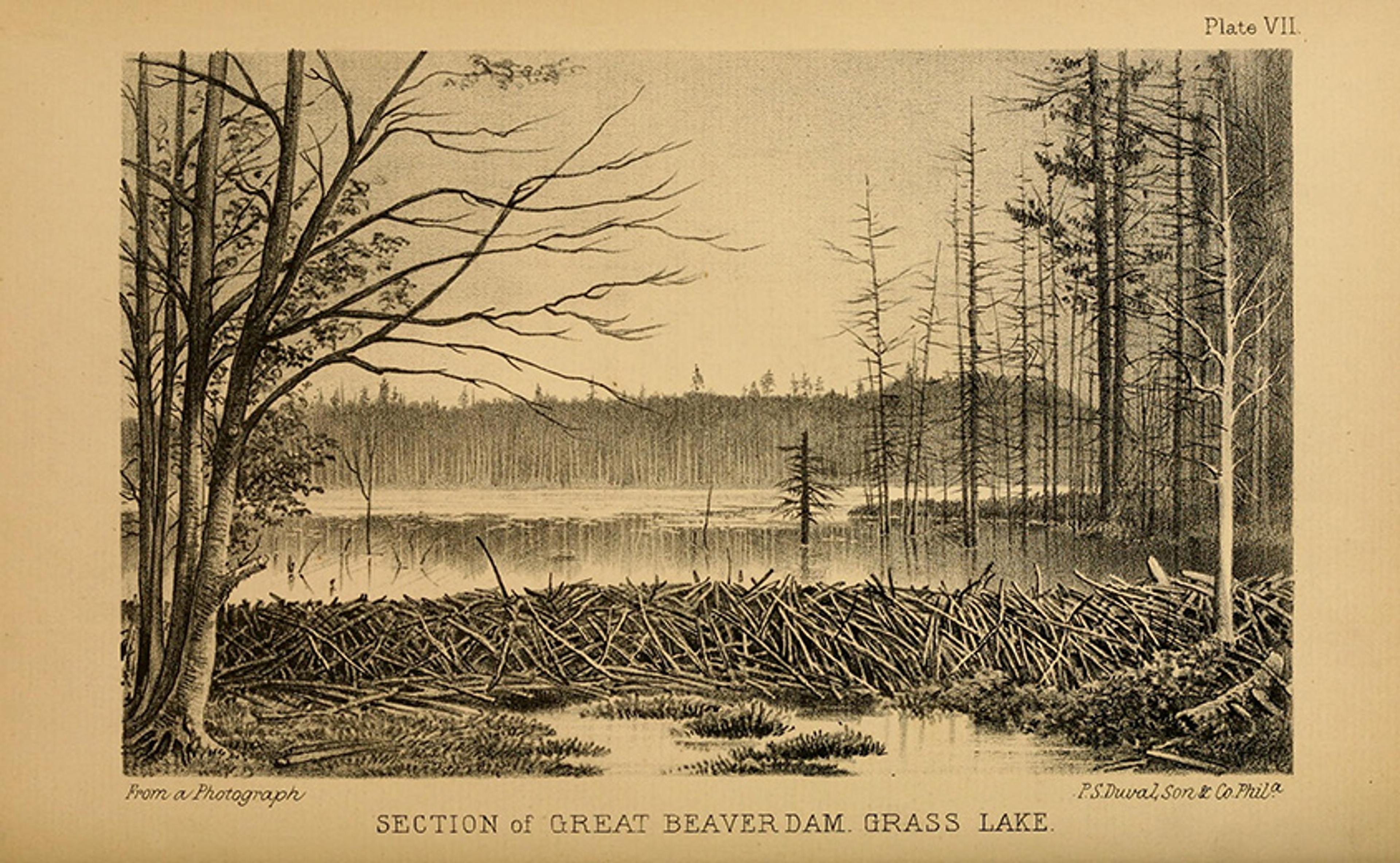

Imitating animals didn’t just lead to the production of art. It may have led to architecture, too. Vitruvius, a Roman architect and engineer of the 1st century BCE, hypothesised that humans were inspired to create architecture by observing how birds and bees built their nests and hives from natural materials to shelter themselves against the elements. In the late 19th century, the lawyer, ethnologist and railroad profiteer Lewis Henry Morgan made similar observations about the parallels between human-made architecture and the structures produced by North American beavers. In his book The American Beaver and His Works (1868), Morgan wrote that this ‘architectural mute’ of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula offered ‘the most remarkable of the few instances occurring among quadrupeds of that architectural instinct … which impels them to construct their own habitations with materials selected for the purpose, brought from a distance, and cemented together so as to form a regular and uniform structure.’ Morgan marvelled at the craftsmanship, strategic placement and ‘highly artistic appearance’ of the beaver dams, which he systematically studied through destructive excavations that any archaeologist might find familiar. ‘I have,’ he wrote, ‘taken up to the bottom both old and new beaver dams, and examined, with some care, the disposition and arrangement of the materials.’ Morgan produced meticulous maps, drawings and photos to document beaver construction styles and techniques, and to illustrate how dams and lodges were adapted to the unique conditions and character of each stream.

From The American Beaver and His Works (1868) by Lewis Henry Morgan. Courtesy Wikimedia

But long before Morgan (and Vitruvius, for that matter), humans had done more than simply recognise the architectural and infrastructural potential of animal shelters. In the area that is now North Yorkshire, England, beavers began settling along the edges of a lake formed at the end of the last Ice Age, known as Lake Flixton. Drawn by the mixed forest of birch, aspen and willow, the beavers dammed small streams around the lake, creating new ponds, wetlands and marshes. Those environments attracted a variety of wildlife, including fish, waterfowl, red deer, elk, wild boar, foxes and wolves. By about 10,000 years ago, it appears that beavers had cleared the forests from the edges of the lake and created habitats full of fish and game animals, enticing humans to settle nearby.

Beavers provided people with architectural models and the very materials with which to build structures

When that ancient lake was transformed into waterlogged peat swamps, a remarkable range of organic evidence from those Mesolithic human communities was preserved. The archaeological site of Star Carr, for example, which was excavated between 1949 and 1951, yielded some of the earliest examples of wooden-made structures in Europe, including a seasonally occupied timber platform along the shore of Lake Flixton.

In the early 1980s, two British archaeologists, John Coles and Bryony Orme (later Coles), decided to re-examine the remains of the wooden platform from Star Carr. Coles and Orme had been working at a site known as the Somerset Levels, where, like Star Carr, ancient wooden remains had been preserved in waterlogged wetlands and peat. Remains from the Somerset Levels included a timber platform similar to the one identified at Star Carr but dated later, to the Neolithic period (about 6,000 years ago). When Coles and Orme examined the platform preserved at the Somerset Levels, they noticed about 40 of the logs used in its construction were unusual: they had not been snapped or chopped cleanly across. Instead, their ends had been cut with a series of parallel facets, a pattern that could not have been produced by Neolithic stone axes or knives. Coles and Orme realised these had been felled by beavers and used to build wooden architecture before humans repurposed the materials for their own structures.

Detrital wood scatter exposed during excavation at Star Carr. Courtesy the Star Carr Project CC BY-NC 4.0

Wood recovered from Star Carr showing chop and tear at distal end (right) and beaver gnawing at the proximal end (left). Courtesy Michael Bamforth, Star Carr Project CC BY-NC 4.0

Coles and Orme inspected the wood that had been used to build the platform at Star Carr several thousand years earlier (and pickled in alcohol since the mid-century excavations at the site). They immediately recognised the same tell-tale marks of beavers on some of Star Carr’s birch branches. Coles and Orme went on to review evidence from many other prehistoric sites across England and Wales. They eventually identified wood with beaver facets in multiple human constructions, along with extensive networks of ancient beaver dams and channels that had been integrated into prehistoric settlements. For millennia, beavers built the lake landscapes and fertile hunting grounds that made human life flourish. As Coles and Orme showed, these animals also provided people with architectural models and, in some cases, the very materials with which to build structures. Yet, the histories we write about Star Carr begin with the human platform-builders, not the beavers.

A reconstruction of the western end of the platform at Star Carr. Courtesy the Star Carr Project

Whether tracing over the grooves left by other animals in caves or borrowing the wooden materials beavers had used to build their homes, early humans paid close attention to the different forms of life around them. That attention also extended to plants. About 8,000 years ago, in the tallgrass prairies of eastern North America, bison fertilised soils, transported seeds, and encouraged the growth of barley, wild squash, sumpweed and sunflowers. Bison, like beavers, are what ecologists term ‘keystone’ species – organisms that hold an environment together, sometimes affecting its structure, character and composition. In tallgrass prairies, bison preferentially graze grasses, especially when the shoots are young and tender, which allows more flowering plants to grow and increases species diversity. Bison also wallow in mud or shallow water to keep cool and avoid insect bites. In the process, they disperse the seeds of plants stuck to their fur, which easily sprout in the well-watered and nitrogen-enriched clearings of bison wallows.

Over time, people and bison became partners in engineering the ecosystems of the prairies

Recently, successful efforts to regenerate native prairies with reintroduced bison have allowed archaeologists and botanists to observe the overlooked effects of bison on early agriculture in North America. Based on fieldwork in the Joseph H Williams Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in eastern Oklahoma, the archaeologist and paleoethnobotanist Natalie Mueller and her colleagues have argued that North American humans who foraged in these landscapes would have noticed the mutualistic relationships between bison and certain plants. As bison moved through the prairies, they created clear trails through the grasses. Travelling along those bison tracks, people would have encountered dense stands of seed-bearing annual plants growing where bison grazed and wallowed.

Growing in small, scattered patches, wild forms of millet, quinoa, sorghum and many other edible species would have offered a low return of energy for the labour required to collect them. However, growing in dense stands in bison-made clearings, these same species would have offered an easier harvest. It’s likely that this observation led humans to propagate and, eventually, domesticate such wild crops. Over time, people and bison became partners in engineering the ecosystems of the prairies. Mueller and her colleagues have shown how the archaeological sites with the earliest evidence for plant domestication coincide with paleoenvironmental sites with evidence for anthropogenic burning. Humans, with our fires, cleared native forests and changed their composition, promoting growth in nut trees and wild fruits, and attracting game animals – including bison – to new edges and clearings. The bison, in turn, created niches for the annual seedbearing plants eventually cultivated by humans.

Recognising the impact other species have had on our art, architecture and agriculture doesn’t require new archaeological discoveries – in fact, much of the archaeological evidence is decades old. Rather, it requires new ways of thinking. The evidence asks us to reconsider our assumptions about human exceptionalism. It asks us to push the limits of history beyond our own story. It asks us to reckon with our ignorance of the past and to face some uncomfortable truths.

It was once unimaginable that cave bears might share responsibility with our ancient ancestors for ‘inventing’ art. Likewise, beavers, hunted to extinction in the British Isles by the late Middle Ages, are not the first explanation that comes to mind for architectural remains at English archaeological sites such as Star Carr. And as for bison, the outsize impacts they had on the biodiversity and structure of tallgrass prairies remained unknown until recent decades because grazing herds had disappeared long before the discipline of ecology came into existence – such herds had been intentionally eradicated as obstacles to the westward expansion of European settlers.

Many of the bear marks, beaver logs, and bison paths that incited new human behaviours come from a time when the divide between human and nonhuman was more porous, when humans were discovering how to be human. That process of discovery was less about our species defining itself against everything else in the world than it was about interactions, observations, mimicry, creativity and experimentation.

The long-held assumption that humans are the only species with deep history – and the oft-repeated claim that archaeology is about only humans – narrow our collective vision of the past and limit the scope of our potential futures. What other fundamental cultural traits could be learned from our animal counterparts if we were to study how animals have made and done things, how they have managed to survive and thrive on this planet?

Culture was never (only) ours. In the archaeological record, Prometheus isn’t a godlike Titan. He is a shaggy cave bear with sharp claws, a beaver with architectural knowledge, a bison turning a prairie into a field of crops.