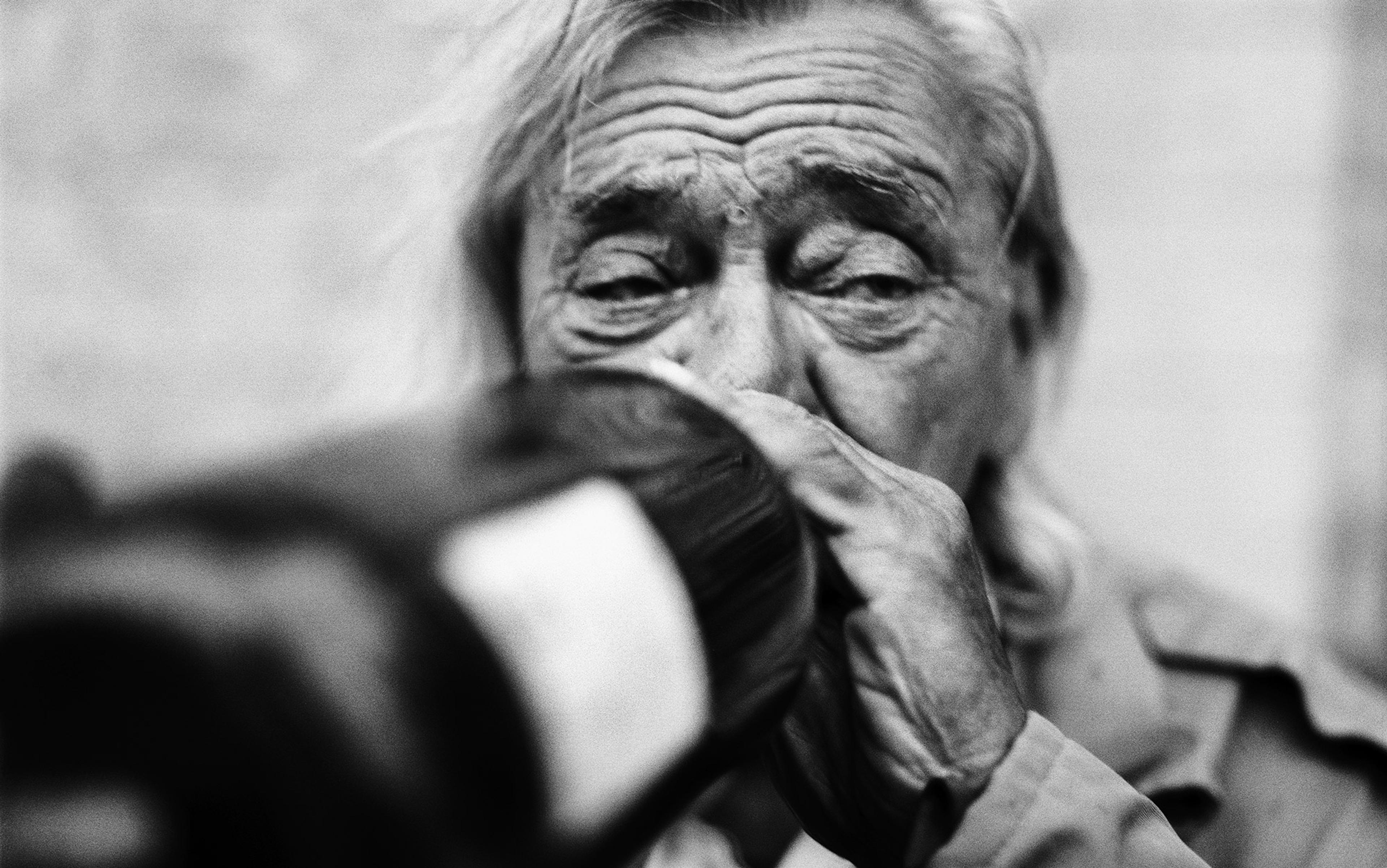

‘I’m at the point in my life where I’ve been doing this 20 years or so. [It’s been] probably 22, 23 years, and I’m ready to quit,’ said Clyde, a long-time methamphetamine user now in his mid-40s. When we met in 2011, he was beginning to grow weary from decades of partying and staying up for days at a time. We sat in a conference room at a homelessness resource centre in Northern Colorado. From across the table, his pale blue eyes were bloodshot with fatigue.

By the time of my first interview with Clyde (not his real name), I’d been conducting research with active meth users for about three years, so his sentiment wasn’t news to me. After all, the highly potent central nervous system stimulant wears out most people eventually. The lack of sleep, the growing paranoia, the skyrocketing proportion of bad days to good all drive users to seek sobriety.

As with many others I studied, Clyde’s use fluctuated, sometimes dwindling to complete abstinence for weeks or even months; he talked frequently about leaving the drug behind for good. But he always went back. Intermittently homeless and plagued by debilitating and difficult-to-treat mental health issues, his circumstances seemed to lock him into his addiction.

Yet Clyde’s story – the part where he doesn’t quit – is not the norm. Most users, even the majority of those so hooked that we label them addicts, recover on their own without ever undergoing formal treatment.

Despite the common trope that trying any illicit drug – even once – will definitively lead to a life of ruin, the vast majority of people quit without such dreadful consequences. According to the United States National Institute on Drug Abuse, drug use peaks for most of us in our late teens and 20s. While more than a fifth of 18- to 25-year-olds have used an illegal substance in the past month, only 15.1 per cent of 26- to 34-year-olds and 6.7 per cent of those 35 and up report current use of illicit drugs.

The 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that roughly half of Americans aged 12 years and older have tried an illegal substance at some point in their life, while just 16.7 per cent have used an illicit drug in the past year. And only 10.2 per cent, the individuals considered ‘current users’, have taken a drug in the past month. These numbers indicate that roughly one in five people who tries an illegal drug will continue using with any regularity. When it comes to ‘hard’ drugs such as heroin or cocaine – in essence, any illegal drug aside from marijuana – fewer than a third of people aged 12 and up have ever used them; 7.4 per cent have indulged in the past year, and 3.3 per cent are current users. So, with pot out of the equation, only about one in 10 people who starts using drugs ends up using on a regular basis.

The numbers for drug dependence or abuse are even lower. According to the same report, 2.7 per cent of Americans aged 12 or older report past-year dependence on or abuse of illegal drugs, and 6.4 per cent report dependence on or abuse of alcohol. Though these percentages are relatively low, especially for ‘hard’ drugs, they still leave us with about 22 million Americans deemed in need of treatment for an alcohol or drug problem.

The fascinating statistic here is that in 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, only 11.6 per cent of those with substance-use disorders received treatment. Yet at least two-thirds of users who become addicted manage to quit or significantly reduce their consumption without formal help.

This suggests that it might be time to look beyond the traditional recovery paradigm and turn to the natural phenomenon of ageing out, or maturing, and what empowers it, for most.

What is ‘ageing out’ anyway? In a 1962 paper for the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Charles Winick proposed that most drug use is probably self-limiting. It might be, he wrote, ‘a function either of the addict’s life cycle or of the number of years that he is addicted, or of some combination of the two processes’. Either way, at least two-thirds of people with substance-use disorders appeared to get clean on their own, representing a goldmine of insights into addiction and recovery. And in recent years, health, social and behavioural researchers have started delving in.

So, what have we learned so far from those who age out of drug use? When people talk about the life cycle leading to natural recovery, numerous factors are at play. For many, it’s a simple case of ‘being sick and tired of being sick and tired’. As was the case for my research participant Clyde, drug use can eventually become incompatible with adult relationships, career goals, social roles (such as parenthood), or even general societal expectations about what constitutes age-appropriate behaviour.

In his 1999 study of natural recovery from alcohol abuse among Navajo Indians, the anthropologist Gilbert Quintero and colleagues at the University of Rochester in New York found that: ‘One of the most persistent and formative influences organising narratives of “ageing out” were the responsibilities and role demands connected to raising children.’ The more that individuals came to embrace their Navajo heritage, the more they expressed a sense that drinking simply didn’t fit anymore. Abstaining from alcohol use became a means of identifying with their culture. Similarly, while binge-drinking is a notorious and often troubling rite of passage for many young Americans, the behaviour – outside of specific contexts – has an expiration date. As we age and seek to fit into cultural moulds, we often change what we do.

My own experience of ageing out is what drew me to study drug use in the first place. Almost 15 years ago, before it had ever occurred to me that one could make a career from studying addiction, I quit meth for the last time. I’d just graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles with a bachelor’s degree in anthropology, and it was my first week as a full-time ‘reservationist’ at a hot new three-star restaurant in New York.

When my roommate and I decided to move across the country, I’d assumed my five-year amphetamine habit would stick close. After all, I’d brought it from the sunny suburbs of Phoenix to the sooty skies of Los Angeles. But on one chilly East Coast morning in early autumn, as the tedium of a nine-to-five schedule and public transit commute set in, I started to tire at the prospect of another night awake. For the first time, I wanted to stop the speed cycle before it started.

As I folded my compact in the palm of my clammy hand, I just felt tired. I’m getting too old for this shit, I thought. It isn’t fun anymore

That last morning, I huddled over an open compact and a baggie of white powder in the cramped, fluorescent-lit stall of a bathroom in a restaurant in lower Manhattan. Stepping out, I scrutinised my pallid, sleep-deprived face in the mirror. I sniffed and, clenching my molars together, jerked my jaw left then right in a grinding twitch as I leaned closer to my reflection. I tilted my chin up and pulled my top lip over my teeth, fixing my saucer-wide-pupil gaze on my nostrils, checking for remnants of the crystalline powder that still burned my sinuses. With a curt nod, I stepped back, heels clacking on the tile, and marched to my station at the ever-ringing phone. ‘Good morning. Thank you for calling The Harrison. How can I help you?’ I chirped as I slid into the rolling chair.

My words spilled out too fast and my mouth was parched within seconds of speaking. I reached for my water and took a swig, smiling at my officemate in hopes she wouldn’t notice my shifting jaw and sour, cold-sweat stench. Within a few hours, the fatigue of being up all night started washing over me again and I slipped back to the bathroom. I tucked myself into a stall and pulled out the familiar straw/compact/baggie/razor combo. It took me seconds to cut a small line and snort. The burn shot through my nasal passages and felt like it would burst from behind my left eye. There was a time when I loved that feeling – it was part of the ritual, amping the anticipation of getting spun out – but not that day. As I folded my compact in the palm of my shaky, clammy hand and flung the door open, I just felt tired. I’m getting too old for this shit, I thought. It isn’t fun anymore.

It was 22 October 2001 and, at almost 22 years old, I had begun to age out of methamphetamine. Over the next several years, I would gradually, and without treatment, abandon binge-drinking, cigarette-smoking and even occasional marijuana use. Though this is the path that’s most common among people who have tried or even become addicted to drugs, it’s the one least discussed. But careful scrutiny of ageing out – both why people do and why they don’t – tells us a lot about drug dependence and what to do about it.

The natural recovery research that has blossomed across disciplines in recent years reveals that ageing out is in fact linked to life phases, but not in a simple or linear way. To understand why some people do and others don’t recover on their own, experience cannot be viewed as if in a vacuum. And we can’t just look at the success stories. Structural factors – from racial inequities to cultural norms to socioeconomic disparities – greatly shape people’s chances of getting sober with or without treatment.

Following a culturally defined and accepted life trajectory can be the key to successfully ageing out of drug or alcohol problems. But finding space in the dominant culture – even if it’s desired – is sometimes out of reach. And in the case of drug use, social structure more often than not becomes a major limiting factor.

My own ethnographic research spanning 2009 to 2014 examined the experiences of active users, not natural recovery explicitly. But on top of learning how people survived at the intersection of addiction, poverty and the war on drugs, I watched many try to cease using or find a manageable level of use. I observed and asked questions as research participants moved (mostly) unsuccessfully through mandated and voluntary treatment programmes and struggled repeatedly to ‘get clean’ on their own. Most returned to methamphetamine use within a few months so, while their experiences shed little light on why ageing out happens, they might offer some insights into the mechanisms at work when it doesn’t.

whenever they came up short of funds for a room for the night, they typically landed on the couch of someone who used meth

Overall, there are important differences between the people who recover from drug and alcohol dependence unassisted and those who end up in treatment. Treatment seekers are more likely to be male, and tend to be younger with more complicated and extreme drug-use histories that often involve multiple substances. Those who have been through treatment also tend to have more mental health issues and less education, financial resources and supportive relationships than their untreated counterparts.

My research showed that homelessness was a particular threat for relapse. As much as Clyde, discussed above, felt like it was probably time to quit, life kept pulling him back in. His recurring homelessness left him and his girlfriend Bonnie (also not her real name) at the mercy of others. When it came to providing physical protection and hustling income, the two had each others’ backs – hence the nicknames I’ve given them here. But whenever Bonnie and Clyde came up short of the funds needed to rent a room for the night, they typically landed on the couch of someone who used meth.

‘We went to these people’s house, this guy’s house, and they did [meth] all the time there. It’s a basement,’ Clyde explained one day over fast-food tacos. He was visibly high – twitching and agitated – despite having told me just weeks prior that he planned to get clean.

Bonnie sat beside him, calmer but with dilated pupils, methodically unwrapping her lunch. ‘The last two weeks, we put ourselves in lots of situations to stay warm and we didn’t get high,’ she said. Alas, at this point, they had been awake for three days.

‘Yeah, and they’re doing it right there around us,’ Clyde said.

‘Those people are awake in the middle of the night when we’re so cold that…’

Unable to wait for Bonnie to finish her sentence, Clyde burst in: ‘We can say, hey, can we crash on your bed?’

Homelessness presented a particular struggle for many of my research participants, who wanted to quit but had to depend on existing networks to survive. As with Bonnie and Clyde, for most this meant turning to the only people who would let them ‘crash’. And that person was nearly always a drug user.

When a self-described addict I’ll call Karen, in her mid-40s, was released from a four-year stint in the state prison, her original housing plan fell through. Her family was unwilling to take her in but a friend, who was also a mid-level dealer, opened her door, and her couch, indefinitely. For the first several weeks, Karen easily met her parole mandate of sobriety. But as time passed and she was unable to find work that would give her the financial stability to move out, she began to struggle in the house.

‘I can still be around [my boyfriend when he’s] high and not use, but not living here when everybody’s high around me. That’s too hard. Especially because the first month I was out [of prison] I fuckin’ did the right thing. I wasn’t getting high, I wasn’t doing shit. And it was like, nothing’s getting better. In fact, things are getting worse. Can’t fucking stand everybody being up tweaking all night and I’m trying to sleep on the couch and that just wasn’t working for me. And then, so I started sleeping out on that bench that I was sitting on out there and then that fire hits and there’s so much fucking ash and stuff out there I couldn’t even breathe when I woke up in the morning,’ she said.

Eventually, Karen got an under-the-table job cleaning houses and moved in with a sober acquaintance across town. Her use declined substantially until the friend sold the house and moved away, leaving Karen without a place of her own once again. Unable to earn enough for a security deposit or rent on her own place, she landed on the streets. For several months, she ran drugs for a friend and shared hotel rooms with other users, and her own meth use escalated.

culture and survival in the face of extreme economic scarcity bound research participants to even the most dysfunctional family and friends

Throughout the years, I watched others grapple with similar situations. Poverty kept them from planning for the future or growing into the ‘provider’ role that would have given them a sense of self-worth. Previous drug convictions kept them from finding the jobs that would bring some stability to their lives. Time after time, generosity toward friends and loved ones cost them their housing, or sobriety. Family members, seeking to protect themselves from the emotional and financial rollercoaster, cut ties and closed doors. Most of my participants believed that the only people they could count on unconditionally were other users.

In a recent study that included gathering ethnographic data from Hispanic American heroin users, Alice Cepeda at the University of Southern California and colleagues uncovered a similar blend of dysfunction and support as a means of getting by. They found that culture and survival in the face of extreme economic scarcity bound research participants to even the most dysfunctional family and friends. This resulted in ‘maturing in’ rather than out of drug use, with addicts becoming increasingly embedded in the lifestyle.

The 2011 study by Anastasia Vogt Yuan at the Virginia Polytechnic and State University looked beyond economic disparities to consider the impact that racial inequity might have on natural recovery. In her research, young black people were less likely than their white counterparts to use or abuse alcohol or to abuse drugs. But she found that the tendency to reduce use with age was far weaker among black people, resulting in a ‘crossover’ point. At a certain age, they went from being less likely to drink or abuse alcohol or drugs to being more likely to do so.

Close examination of experience revealed that ‘differential opportunities in social roles (particularly family roles) due to structural disadvantages over the life course limit blacks’ ability to age out of deviance relative to whites’. In other words, because of deeply institutionalised inequalities, black people and other marginalised groups have limited access to the highly valued traditional social roles that tend to trigger the ageing-out transition.

The ageing-out phenomenon offers solace in the face of inadequate drug-treatment programmes, but it also adds fuel to a far bigger fire. The so-called unbreakable cycle of addiction appears to result from inequity – from poverty, from discrimination, from social and economic oppression. Without opening the doors of opportunity, without access to the roles that social, economic and political capital provides, oppressed groups might find it more challenging to cease their drug use, whether they receive formal treatment in a programme or not.