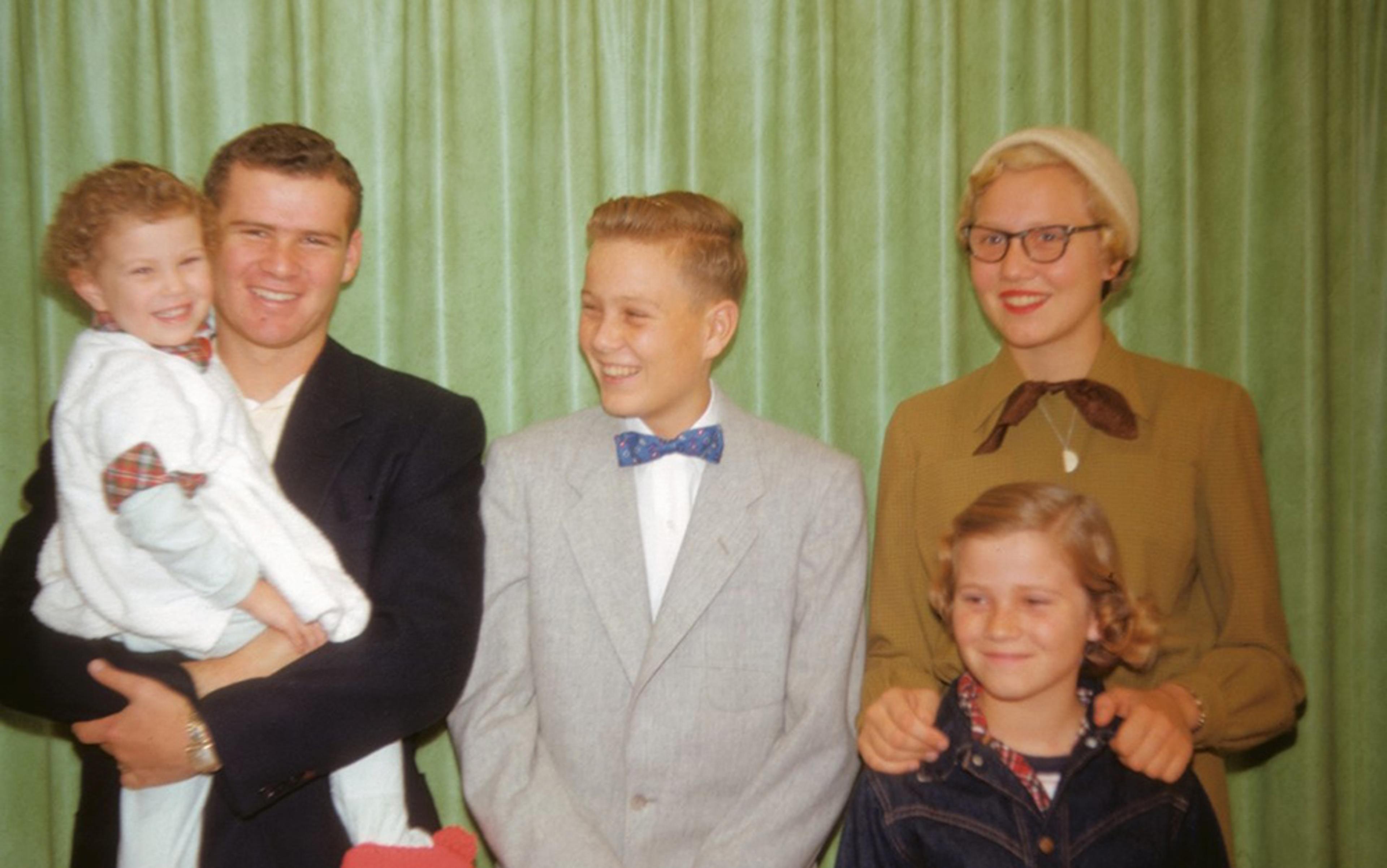

Somewhere in the recesses of my online presence, I keep a virtual pinboard called ‘Nostalgia’. Its images are like stills from a jaggedy film of my childhood: a Rainbow Brite doll, her yarn hair pulled into a fat ponytail. An A4 Trapper Keeper binder with an acid-trip cover. Models in moon boots marching across a magazine spread of a 1996 issue of Seventeen. Brown leather oxfords with the lace ends wound into corkscrew-shaped knots.

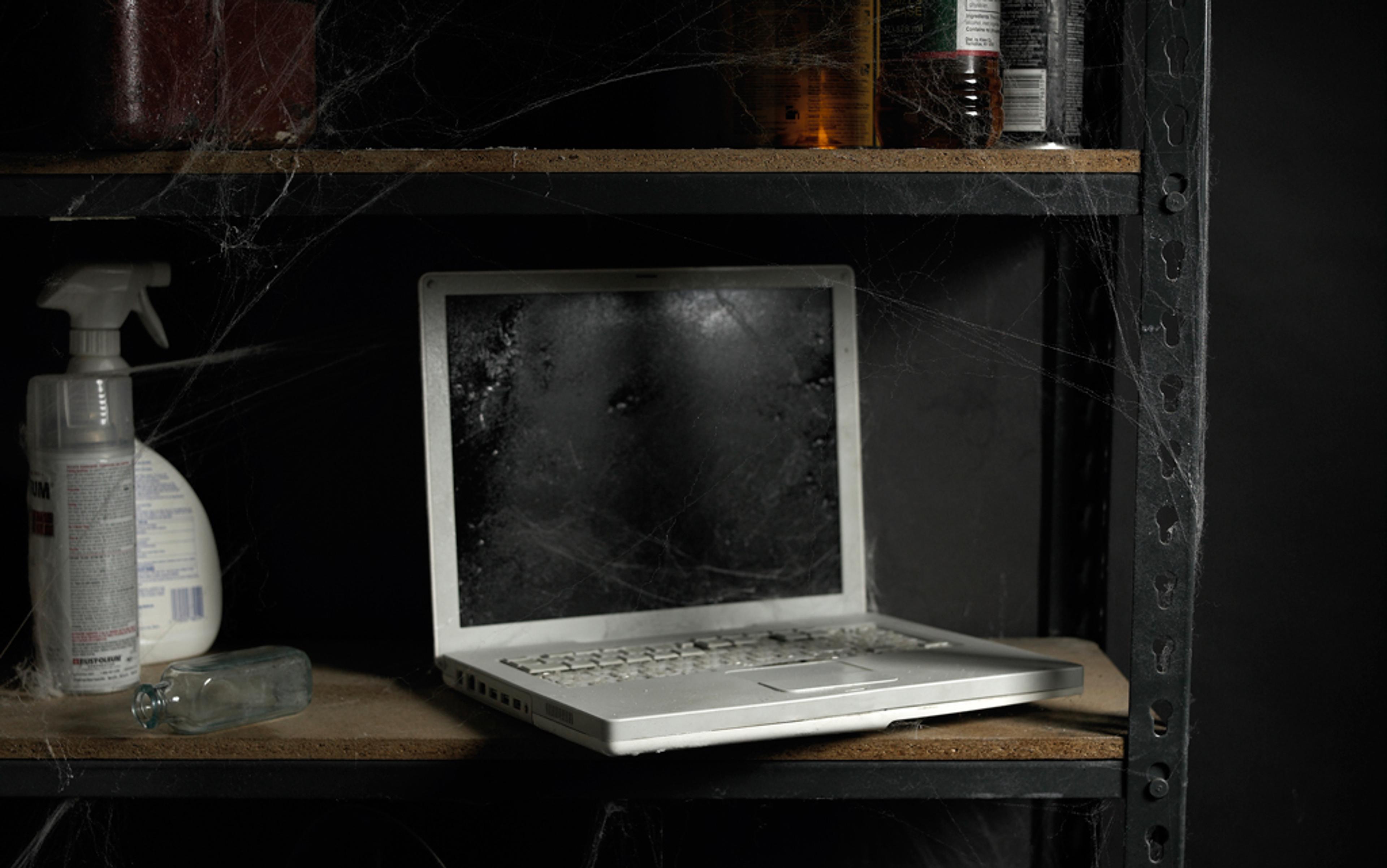

For years, I felt a subtle kind of embarrassment whenever I added to this board. Had someone else walked into the room, I would have closed the browser window. Combing through these old images – each of them bog-heavy with emotional resonance – seemed like just another way to procrastinate. It also felt nakedly frivolous. What purpose could photos of The Baby-Sitters Club book covers or orange mall storefronts possibly serve in the present? What could I hope to gain from inhaling the imagined scent of the scratch-and-sniff stickers my first-grade teacher put on my papers?

Even so, I couldn’t bring myself to stop. Each thumbnail graphic was an invitation to ride a mental slipstream that could buoy me along for 20 minutes or two hours. Swirling in the eddies of reminiscence brought on a flow state in which I felt outside of time yet acutely conscious of its passage.

What nagged at me afterward, besides shame at having frittered away work time, was that I had no idea why I was so determined to spelunk into my past. I started poring over experimental studies on nostalgia – which felt like a more productive alternative to nostalgising – and reached a conclusion I hadn’t expected. The research showed that, far from lulling me into a click-driven stupor, my nostalgic journeys were feeding my inner stability, even girding me to pursue new opportunities I hadn’t yet imagined.

Long derided as a crutch, something we fall back on when the appeal of the present dims, nostalgia is a surprisingly sturdy launch point into the future. Not only does it ground us mentally and physically when the landscape shifts or founders, it focuses us, with sensory immediacy, on what we most value – and, by extension, on what we want to reflect to the world. That’s where its transformative power lies.

Our collective disdain for plumbing our own past depths has hundreds of years of historical precedent. The word ‘nostalgia’, coined in the 1600s by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer, is a portmanteau of the Greek words nostos (‘return’) and algos (‘pain’), implying that reflections on the past are shot through with suffering. Hofer used the word to describe a purported malady seen in Swiss mercenary soldiers who pined for their homeland. He believed that the disease’s symptoms – including bouts of weeping and a lack of appetite – were caused by ‘vibration of animal spirits through those fibres of the middle brain in which … the ideas of the Fatherland still cling’.

Nostalgia’s reputation scarcely improved during the Victorian era, when doctors defined it as a psychiatric disorder marked by rumination about times and places that could never be revisited. The condition, according to psychoanalysts, arose from a thwarted desire to regress to the early stages of life.

It wasn’t until years later that a warmer, fuzzier aura appeared around nostalgia. The French writer Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past (1913-27) – in which the narrator tastes a madeleine cake that lets loose a torrent of memories – did much to humanise the act of reminiscence over time. But while most critics no longer viewed nostalgia as pathology, plenty still saw it as a pointless indulgence on a par with mud masques or gold-flecked hamburgers. Writing, dismissively, in a 1993 issue of The Baffler, Tom Vanderbilt said:

Nostalgia is a form of propaganda, an exercise in laughter and forgetting, in which the right visual iconography and perceived authenticity can create a longing for an existence which is no longer possible and was in fact never possible.

It wasn’t long before such warnings were ploughed under by a nostalgia movement that took root on social media (and, before that, in AOL chatrooms). Spurred on by dejected millennials and Gen-Ys who yearned for a portal to a simpler time, this movement now shapes the contours of the online economy. Viral headlines such as ‘50 Things Only ’80s Kids Can Understand’ fuel more clicks than breaking national news. Meanwhile, canny advertisers are using online pinboards such as mine as opportunities to market throwback goods – ‘nostalgia porn’ – to generations that seized on the pastime of reminiscence decades before anyone expected.

In the face of a raging pandemic, political turmoil, relational discord and yo-yoing financial markets, it’s easy to see nostalgia’s furious popularity as evidence that we refuse to engage with current-day calamities. What psychologists are reporting, however, is something more intriguing and nuanced: we delve into the past precisely so that we can feel grounded enough to face up to the challenges of the present.

In anchoring us in our own history, nostalgia helps to create a consistent sense of identity, which is the stabilising force we need to face problems – whether personal or global. For example, in the context of an abusive relationship, ‘a survivor can internalise what the abuser is doing’, says the psychologist Krystine Batcho of Le Moyne College in New York state. ‘They come to the conclusion: I’m not worthy of being loved.’ But looking back on happier times can flip this damaging script. ‘When they reminisce,’ she continues, ‘they can say: Wait a minute. There were people who treated me with respect and dignity.’

This helps to explain why dipping into nostalgic memories helps people feel a stronger sense of belonging and more belief in their own potential. ‘Nostalgia,’ says Andrew Abeyta, a psychologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey, ‘makes people more optimistic in a broad sense that things are going to work out for them.’

This optimism is heightened because most of us are more likely to dredge up positive memories from the past than negative ones – a bias psychologists call the ‘Pollyanna principle’. When people tell nostalgic stories, according to a report from the University of Southampton in the UK, they use more optimistic phrases than in stories they tell about everyday events.

Such memories help us believe that we can reach similar social pinnacles in the future

This rosy view of the past helps to balance out the corrosive snap judgments that pile up in everyday life. If your supervisor stuns you with a poor performance report, your brain will likely fire off a volley of negative thoughts: I’m not good enough or I’m such a screw-up. But if your mind turns back to other times when you were aceing work assignments and felt more capable, those memories can offset the self-doubts you’re battling in the present. There’s biological evidence for this balancing effect: a brain study from North Dakota State University showed that nostalgic detours appear to soften the perceived sharp edges of negative events.

Nostalgia also spurs us to rally other people around us in ways that bolster our health and wellbeing. In one study, Abeyta and his colleagues asked some people to bring a nostalgic memory to mind, and others to reflect on an everyday event. Those in the nostalgic-memory group more often reported wanting to get close to other people afterward. Most likely, Abeyta says, this is because revisiting old memories reminds us of times when we felt fulfilled in the company of others – and such memories help us believe that we can reach similar social pinnacles in the future.

‘One way we as psychologists try to promote self-confidence is by creating experiences where people can see themselves succeed,’ Abeyta says. ‘People are bringing to mind these very successful special relationships: “You know, I have had success in this social domain.”’ This kind of insight can make us bold enough to weave a social safety net that keeps loneliness and failing health at bay.

Most crucially, nostalgia appears to offer people a foothold when they have few remaining rungs to stand on. In a new dementia treatment called ‘reminiscence therapy’, therapists use prompts such as photos, objects or music tracks to trigger conversations and reflections about a person’s deepest memories. A review of reminiscence-therapy studies found that this approach had positive effects on clients’ cognitive performance, communication skills and mood, although its authors, from Bangor University in Wales, stress the need for controlled trials of the therapy.

Whether our memories stretch back 80 years or just a decade or two, the episodes that resurface serve as a sort of Rorschach test, revealing what we value and the kinds of experiences we cherish. If you like to recall Chuck E Cheese birthday parties, you likely prize the security of a big, gregarious community, while memories of making chalk drawings with your best friend hint at a desire for deeper, more sustained bonds. ‘Experiences are not just what happen to us,’ writes Batcho. ‘They are the raw material we use in shaping our identity, our self.’ Nostalgia, then, is a means of reclaiming that raw material, making intimate contact with it as though sinking our hands into clay.

This primal contact with what animates us can help to fuel belief in the significance of our lives. When Clay Routledge, a behavioural scientist at North Dakota State, and colleagues asked college students to reminisce about a nostalgic memory or think about a desired future event, members of the nostalgia group were most likely to report that their lives were rich with meaning. Still, it can be challenging to trace a clear path from certain nostalgic objects – in all their ordinary, frivolous, consumerist glory – to the profound sense of meaning the research describes. It seems straightforward that when I pull down an old yearbook, complete with photos, captions, and inscriptions, I’m reviving memories of a whole world I left behind. But a nostalgic obsession with Donkey Kong or the My Little Pony stable might seem to have less to do with essential aspects of the self.

However, as Proust well understood, each point of nostalgic reference – whether a smell, a product, or a snippet of song – conjures up an inner world unto itself, exquisitely rich in detail. The chorus to Deep Purple’s ‘Smoke on the Water’ (1972), or the Cabbage Patch Kid with a heart marker-scrawled on its cheek, is pure synecdoche. It is a fragment that stands in for the entire vanished universe that surrounded it: the characters that peopled it, the beliefs that suffused it, the emotions that pervaded it.

Just as Proust’s madeleine ushered him into his own lost world, a corn muffin or johnnycake propels me into the landscape of upstate New York as I experienced it aged four, swinging my legs at the counter of Howard Johnson’s restaurant while my dad ordered corn toasties for breakfast. It’s not the object of nostalgia that’s important in and of itself. It’s that it serves as a conduit to realms of thought and emotion that we can’t always access without it.

In evoking security, self-assurance and a sense of meaning, nostalgia sets the stage for profound personal growth – a willingness to venture beyond our physical and psychological borders. Fortified by the knowledge that we can return to our inner Ithaca when we need to, we’re better equipped to push our borders outward – or to topple them entirely.

It was these detours into happier times that steeled Frankl through Auschwitz

To test this theory, the psychologists Matthew Baldwin and Mark Landau at the University of Kansas asked people to think about a past event that provoked nostalgia. They then tested how much those nostalgisers agreed with statements such as: ‘I am the kind of person who embraces unfamiliar people, events, and places.’ The researchers found that subjects in the nostalgia group had a stronger sense of belonging and more belief in their own potential. ‘Nostalgia,’ they wrote, ‘serves as a psychological resource that maintains and recycles, through memories of actual events, the distinct positive emotions that broaden and build thought-action possibilities.’

The growth-promoting influence of nostalgia might be most critical in the blackest periods of our lives. In the cesspool of Auschwitz, the Jewish psychiatrist Viktor Frankl continually called up memories of his wife to remind himself, despite his present hell, of the persistence of fulfilling human relationships. It was these detours into happier times, and the positive emotions that went with them, that steeled Frankl through deprivation, slave labour and typhus epidemics.

The existential triumph that Frankl recounts in his memoir Man’s Search for Meaning (1946) – his ability to live meaningfully, even thrive, under the worst possible conditions – was tethered to his skill at invoking joyful episodes from his past:

In a position of utter desolation, when his only achievement may consist in enduring his sufferings in the right way … in such a position man can, through loving contemplation of the image he carries of his beloved, achieve fulfilment.

Justice activists, too, often wax nostalgic as they brace themselves to tackle feats most consider out of reach. When Batcho analysed the memoirs of Ukrainians who took part in resistance movements during the Second World War, she found that revisiting childhood values drove many towards deciding to undertake a freedom struggle with no guarantee of success.

Joining Ukraine’s resistance prompted the nostalgic young warrior Luba Komar to recall her earliest memories of growing up in a Ukrainian village. ‘We played games, danced, and sang songs,’ Komar told her daughter Christine Prokop in Scratches on a Prison Wall (2009). ‘Women brought their spinning wheels and sat in a circle … spinning yarn and stories.’ Some of the songs and stories were about freedom and the glory of pursuing it, and Komar clung to her memories of these tales as she fought on through ambushes, interrogations and threats to her life.

Nostalgia can propel us through phases of growth even if we never pass through the same crucibles as Komar or Frankl. I coped with a period of stupefying depression by re-reading dogeared old books by Scott Peck about dedication to truth, as well as talking to a good high-school friend and reminiscing about my beloved grandmother. The memories I invoked anchored me as I rode the choppy waters of recovery – and later on, as I wrote openly about my illness for the first time, hoping to establish a small beachhead for others who felt exiled from their own selves.

The kind of nostalgia that promotes security and growth is what Batcho calls ‘personal nostalgia’. It’s the Proustian variety: the rabbit trails of specific memories we retrace in our minds when some impulse beckons us. Yet when these rabbit trails merge into a superhighway – when nostalgia veers from the personal into the dogmatic and collective – it can swiftly turn toxic. We see this in the clamours of greying populations to restore a uniform cultural landscape where belief systems were passed down, unchanged, like birthrights. Such movements, with their echoes of ‘blood and soil’, run not on the fuel of personal memory, but on abstract ideals of a past that might have never, in fact, existed.

This poisonous subspecies of nostalgia arises when true believers foist a sanitised vision of the past on a group of followers. Nostalgia portends ‘good things for you individually as you recapture your own personal past,’ says Frank McAndrew, a psychologist at Knox College in Illinois. ‘But if you take this attitude that everything was better [back then], you’re trying to impose your nostalgia on other people.’ Under such coercive conditions, collective nostalgia can take on the wildfire quality of fundamentalist religion.

Nostalgia that privileges group norms can also breed prejudice. The psychologists Constantine Sedikides and Tim Wildschut at the University of Southampton and colleagues sparked collective nostalgia in Greek students by having them write or read about Greek music and cultural traditions. Afterward, the students reported increased love for their Greek heritage, voicing a preference for Greek TV shows and consumer products. But there was an attendant dark side: they also reported more disdain for foods and products that were not Greek.

‘There’s a balancing act: you don’t want to live there, you want to visit’

With collective nostalgia, Batcho says, ‘what can happen is it turns into in-group and out-group: I want to return to the way things were, and I’m going to find like-minded people.’ In such a formulation, anyone who threatens this mission becomes the out-group. Personal nostalgia, by contrast, is idiosyncratic, largely apolitical, and can take the wind out of prejudice’s sails. When people in one study reminisced about an event they’d enjoyed with a particular overweight person, they later also reported more positive attitudes to overweight people as a whole.

Unlike collectivist bids to look backward, our personal remembrances of things past put us in touch with our stable foundations within. In calling forth our strongest and most elemental qualities, nostalgia prepares us to surmount obstacles, persist through forbidding odds, and venture beyond what we know. And despite Hofer’s dire warnings, most of us don’t need to worry about overdosing on reminiscence – we have an intuitive sense of when to pull away.

‘The bitter part of bittersweet,’ Batcho says, ‘the sadness you feel when you think about things that can never be reclaimed, should be enough to propel you out of your nostalgic reverie.’ McAndrew agrees: ‘There’s a balancing act between going there enough to give you that warm fuzzy feeling, but not letting it swallow you up. You don’t want to live there, you want to visit.’

For my part, I no longer feel guilt over adding to my nostalgia pinboard, knowing that what might seem like mindless clicking helps to steady and motivate me in uncertain times. Yet I feel compelled to push further, to define what it is about my nostalgic triggers that draws me in. How does each of my own private madeleines – whether a Girl Scout sash, a snapshot of a family Thanksgiving, or a 1980s edition of Candy Land – reflect a goal or conviction that drives me?

Instead of letting my nostalgia steer me, I aim to master it. Like Proust, I want to use it to survey the receding tapestry of my life, pick out the threads that are most integral, and follow them as I venture into the unknown. As Proust wrote:

The smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment, amid the ruins of all the rest … I hope at least to be able to call upon the tea for it again and to find it there presently, intact and at my disposal, for my final enlightenment.