The planet is going to hell in a hand basket. Population grows exponentially, the air is toxic, and there simply aren’t enough resources to go around. The Earth could not sustain even a third of its current population were we all to consume at American levels. This fundamental gap succinctly describes the environmental ‘crisis’ for what it is: a problem of equity. In New York, we’ve just inaugurated a new mayor, Bill de Blasio, who campaigned in opposition to what he called our ‘tale of two cities’ – the dramatic and growing levels of inequality that increasingly characterise not just New York, but the country. In fact, it’s a tale of two planets.

The only solution is to harmonise needs and resources. But whom can we trust to do this? In an era of incompetent nation states and predatory transnationals, we must ratchet up local self-reliance, and the most logical increment of organisation (and resistance) is the city.

With this in mind, Terreform – the New York-based research centre I founded in 2006 to investigate the forms and practices of just and sustainable architecture and urbanism – has been conducting a thought and design experiment for the past six years. Called New York City (Steady) State, this experiment seeks to investigate just how autonomous NYC can become in its key respiratory functions: food, waste, water, movement, construction, air quality, manufacture, and local climate. At the margin, this research seeks to determine whether the city can become completely self-sufficient in these vital areas, although our broader ambition is to compile an encyclopedia of the architectural and urban forms and technologies that will be critical for cities around the world seeking greater responsibility for their own ecological footprints.

I use the word ‘responsibility’ advisedly. Too often questions of sustainability are thought of as simply technical, a matter of photovoltaic cells and anaerobic digesters. Our intention is not to politicise these problems in an abstract or purely polemical way but to investigate the real intersection between sustainable practices and the various ways of living that will best help realise them. Of course, history is full of experiments in self-sufficiency (we all fended for ourselves in the state of nature!) but we’re particularly interested in larger-scale and more contemporary instances. There is a name for this – autarky, a politics based on the idea of economic self-sufficiency. The key to the concept is a closed system, a notion also critical to sustainability, where we often speak of closed loops, net-zero, or cradle‑to‑cradle cycles.

Politically, autarky does not have an entirely savoury reputation, carrying, at one extreme, the taint of totalitarianism. But it also connects with that great advocate for urban neighbourhoods, Jane Jacobs, as well as with the kibbutz, the organopónico farming of Havana, and a variety of intentional communities that have sought – via their independence – to establish peaceable and responsibly self-reliant kingdoms. Jacobs is particularly important to our work, not simply because she is the patron saint of New York urbanism, but because of her economic ideas. In particular, she described the economic driver of urban growth as import replacement – the process of increased productive diversification whereby cities become progressively more autonomous in their output.

Like autarky, import substitution stands in something of a bad odour among the neoliberal economic establishment, where it’s seen as a failed experiment undertaken in the early post-war years by countries like India that wanted to rapidly industrialise, throwing off the economic yoke of their former colonisers. While the Indian experience – which included protectionism, and subsidies for developing local capacity – was certainly problematic, and while many similar experiments in the developing world were at least partly inspired by a delusionally rosy picture of the pre-war Soviet Union, a number of countries (particularly in the southern cone of Latin America) had good success with the strategy, showing rapid improvement across a range of social indicators – literacy, public health, nutrition – under this regime.

Today, the burgeoning field of ecological economics and the powerful movements for localism around the world – including tactical and DIY urbanism – are revisiting ideas about community independence, and inspiring us. In New York City (Steady) State, we choose to work at the scale of the city not just because we’re urbanists but because cities are the most logical – and tractable – hubs of self-regulation. Our experiment has deliberate affinities with research by ecologists into ‘patch dynamics’, in which the very arbitrariness of the boundary prompts a particular class of revelation. By confining our study to New York’s five boroughs, we impose an almost completely ‘unnatural’ limit. But it is also meaningful and precise as it reflects fundamentally on a powerful set of political and cultural traditions, and defines an authentic body politic – the necessary instrument for actually enabling co-operative change.

At Terreform, we began with a focus on food. New York is a city of foodies with a staggering profusion of cuisines, and it has bred an advanced discourse about nutrition, organisation, justice, technology, and culture. It abounds with community gardens, with increasingly large commercial farming, and other sites of production, from backyards to rooftops to the tofu-producing cellars of Chinatown, but also with a rich distributive infrastructure of food co‑ops, farmers’ markets, meals‑on‑wheels, soup kitchens, school cafeterias and restaurants. The question for us was: how can all of this be elaborated into more supple and comprehensive networks that take account of our transformed habits and desires? And, to what degree could this be scaled up to feed 8.5 million people?

the energy required to light, heat, and build all of this approximates the output of 25 nuclear power plants

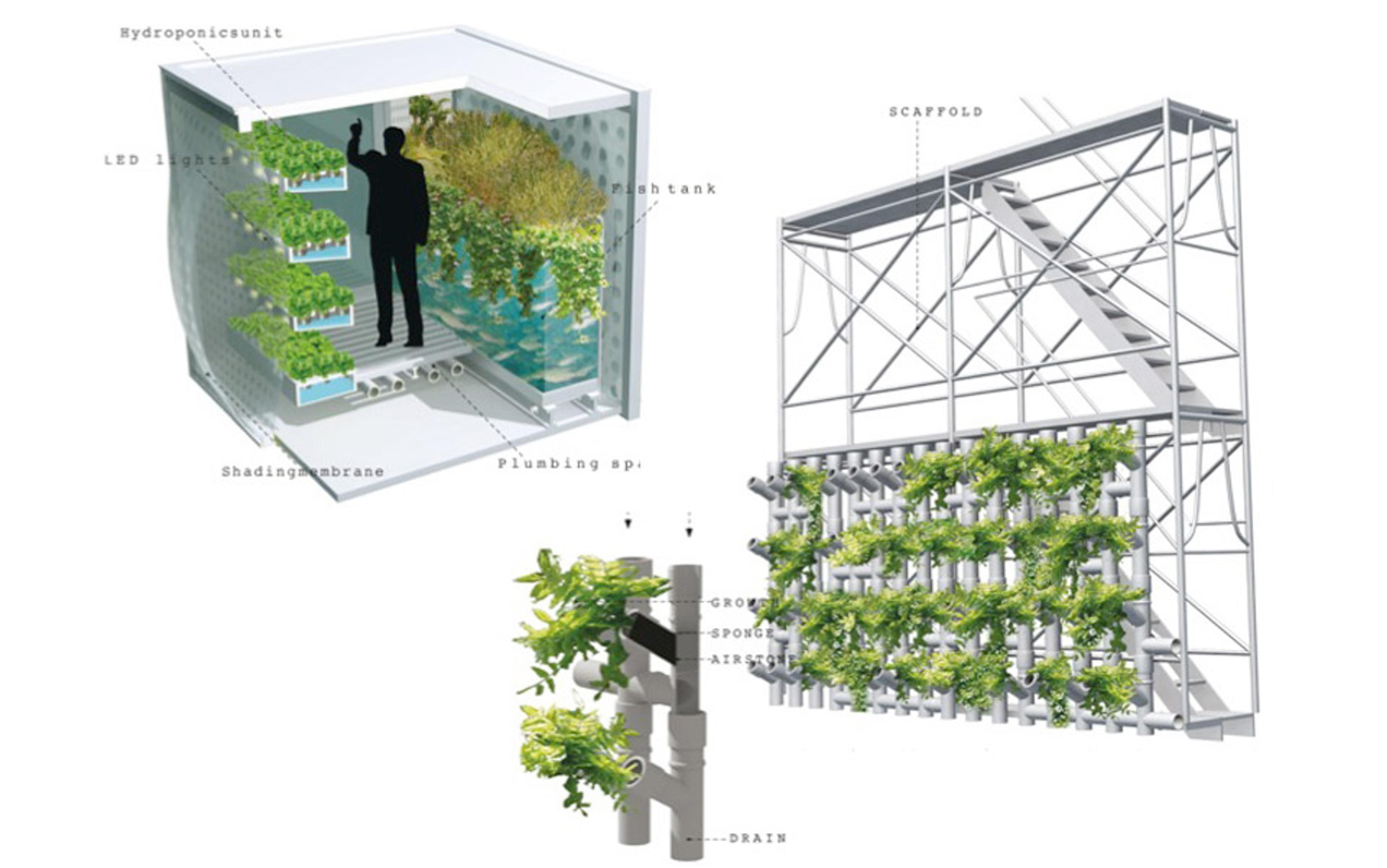

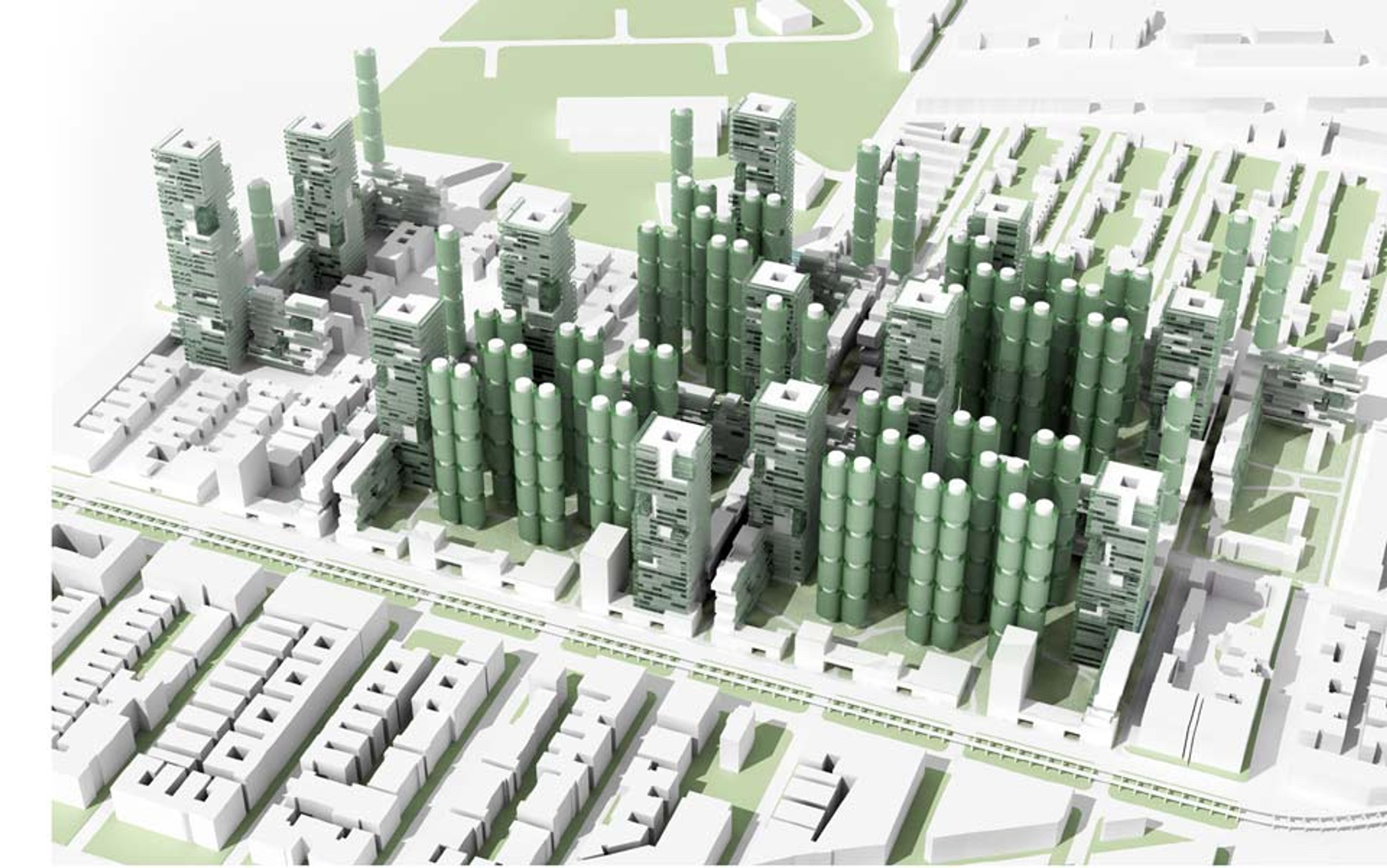

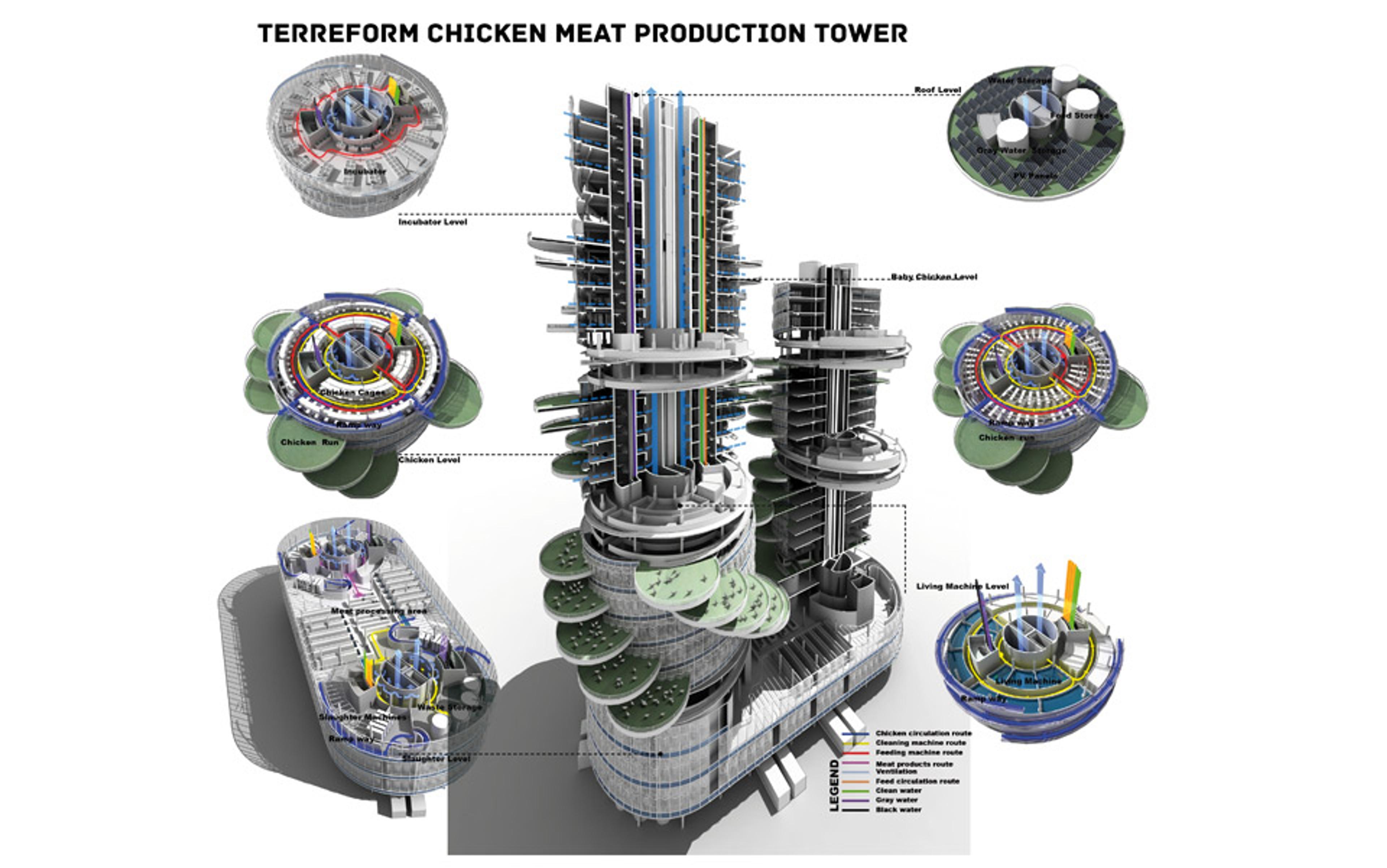

We discovered that it is in fact technically feasible to produce 2,500 nutritious calories a day for everyone in the city. At one level, the required infrastructure is not entirely outlandish. It would depend on the widespread use of vertical farming, building over existing infrastructure – railways, highways, factories, etc – and the densification of some parts of the city currently built at suburban scale. The cost, however, would be prodigious and many of the implications highly vexed. For example, the energy required to light, heat, and build all of this is, we’ve calculated, approximately equivalent to the output of 25 nuclear power plants, an eventuality that is, to put it mildly, somewhat at odds with our larger intentions. Likewise, the necessarily industrialised character of such production would beg the question of resisting the tender mercies of agri-business and the huge variety of its downside effects.

But, by finding a series of ‘sweet spots’, or more nominally ‘practical’ scales for sustainable food production, we’ve sought to balance cost and benefit socially, environmentally, economically, and culturally. We’ve looked at window boxes; at using the subways for freight; at a scheme encompassing the territory with a 100-mile radius around the city; and at reusing the 19th-century Erie Canal for a statewide system. We’ve recaptured street space, designed skyscraper farms for plants and animals, and plotted how to integrate all this into the fabric of the existing city. And, we’ve sought to deepen the idea of the urban neighbourhood as the core unit of sustainable urban organisation.

On the whole, we’re sanguine about the differences between the logics of comparative advantage and the politics of self-realisation, and the difficulties of negotiating the territory in between. New York owns a watershed upstate and a remarkable set of aqueducts to bring what it captures to the city. It makes little sense to grow most grains in the city when they are produced and transported so efficiently from the Midwest. At the broadest level, we know perfectly well that we’ll be ever dependent on the Amazon basin for oxygen supplies, but still seek to un-stress it by moving towards a carbon-neutral city. And the membrane around the self-sufficient city must be permeable to ideas, to people, and to outward-flowing forms of assistance to our neighbours around the globe.

But if we are going to come to grips with the twin catastrophes of environmental degradation and social inequality, we need to begin at home. By truly taking responsibility for the cycles of our own production and waste, we can help increase opportunity for all. As Terreform’s research continues, we will investigate not simply the practical limits of ‘complete’ self-reliance, but also give shape to the architectural and social forms that will help ensure that New York is not simply sustainable but convivial and beautiful. On a planet on which the urban population is growing by a million people a week and on which half of us already live in cities, we seek to turn crisis to opportunity by imagining the forms of a happy future.