In the late 1990s, Google demolished the competition of other search engines because of an extraordinary innovation developed by Sergey Brin and Larry Page: the PageRank algorithm. While older search engines, such as AltaVista, Yahoo and (who can forget) Ask Jeeves, relied primarily on matching the terms of the user’s query to the frequency of the same and similar terms on webpages, Google found more useful websites by tracking which pages had the highest quantity and quality of incoming links. The foundational idea behind PageRank is that a ‘web page is important if it is pointed to by other important pages’. Brin and Page realised that the web is not just a lexical environment but a social one, in which links correspond to prestige, and the sites at the centre of the networks tended to be the most reliable ones. Page later remarked that other search engines ‘were looking only at text and not considering this other signal.’

The idea behind PageRank wasn’t new. The sociologist John R Seeley wrote in 1949 that ‘a person is prestigious if he is endorsed by prestigious people.’ In 1976, Gabriel Pinski and Francis Narin applied a similar approach to bibliometrics, claiming that: ‘A journal is influential if it is cited by other influential journals.’ What was new about PageRank, however, was its application to the web. PageRank succeeded because it recognised that language isn’t made in a vacuum. Patterns of words depend upon other forms of affiliation: the social and physical connections that make the web a representation of the real world.

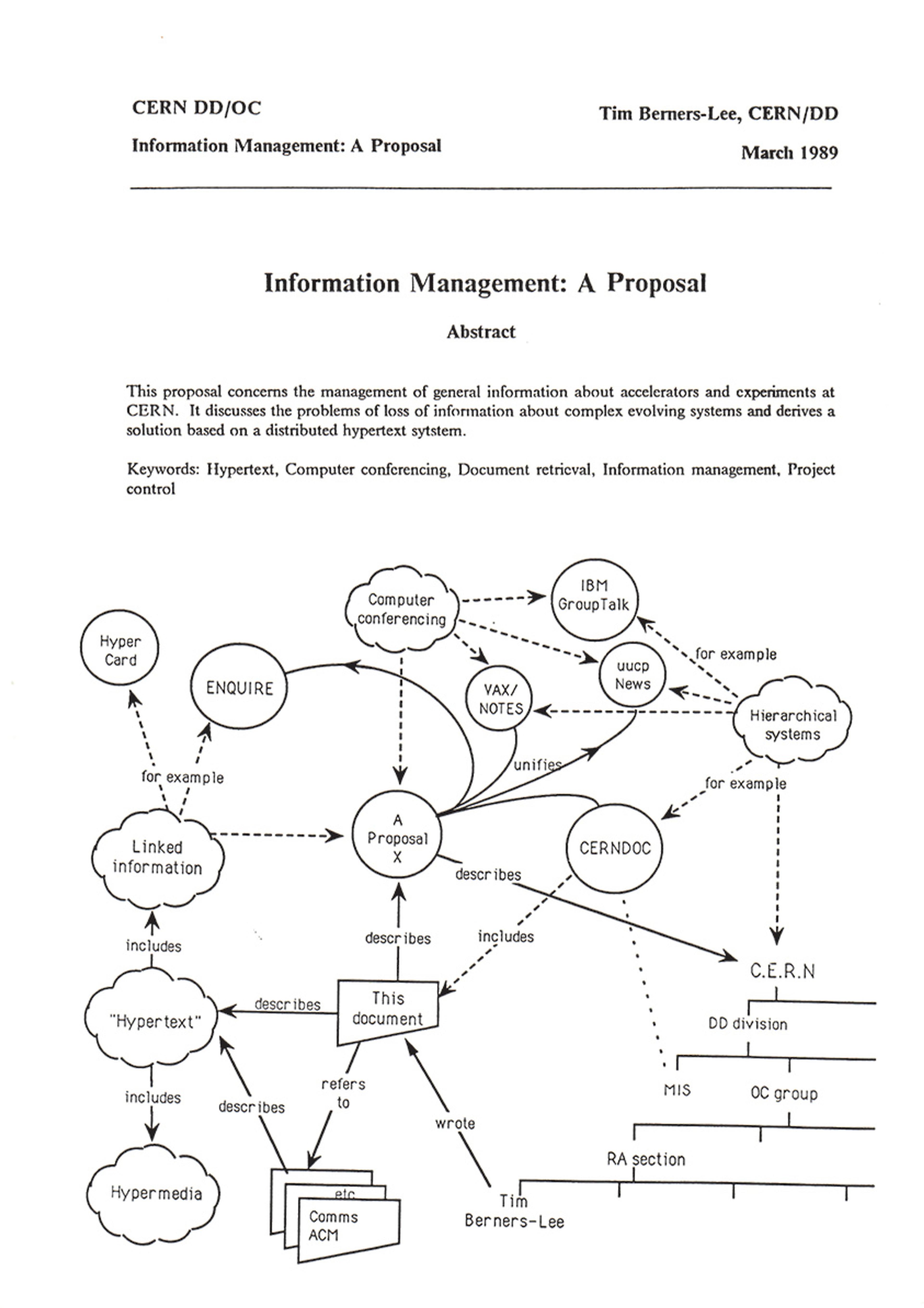

The first page of Tim Berners-Lee’s proposal for the World Wide Web in March 1989. Courtesy CERN

One reason hyperlinks work like they do – why they index other kinds of affiliation – is that they were first devised to exhibit the connections researchers made among different sources as they developed new ideas. Early plans for what became the hypertext protocol of Tim Berners-Lee’s World Wide Web were presented as tools for documenting how human minds tend to move from idea to idea, connecting external stimuli and internal reflections. Links treat creativity as the work of remediating and remaking, which is foregrounded in the slogan for Google Scholar: ‘Stand on the shoulders of giants.’

But now Google and other websites are moving away from relying on links in favour of artificial intelligence chatbots. Considered as preserved trails of connected ideas, links make sense as early victims of the AI revolution since large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini and others abstract the information represented online and present it in source-less summaries. We are at a moment in the history of the web in which the link itself – the countless connections made by website creators, the endless tapestry of ideas woven together throughout the web – is in danger of going extinct. So it’s pertinent to ask: how did links come to represent information in the first place? And what’s at stake in the movement away from links toward AI chat interfaces?

To answer these questions, we need to go back to the 17th century, when writers and philosophers developed the theory of mind that ultimately inspired early hypertext plans. In this era, prominent philosophers, including Thomas Hobbes and John Locke, debated the extent to which a person controls the succession of ideas that appears in her mind. They posited that the succession of ideas reflects the interaction between the data received from the senses and one’s mental faculties – reason and imagination. Subsequently, David Hume argued that all successive ideas are linked by association. He enumerated three kinds of associative connections among ideas: resemblance, contiguity, and cause and effect. In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), Hume offers examples of each relationship:

A picture naturally leads our thoughts to the original: the mention of one apartment in a building naturally introduces an enquiry or discourse concerning the others: and if we think of a wound, we can scarcely forbear reflecting on the pain which follows it.

The mind follows connections found in the world. Locke and Hume believed that all human knowledge comes from experience, and so they had to explain how the mind receives, processes and stores external data. They often reached for media metaphors to describe the relationship between the mind and the world. Locke compared the mind to a blank tablet, a cabinet and a camera obscura. Hume relied on the language of printing to distinguish between the vivacity of impressions imprinted upon one’s senses and the ideas recalled in the mind.

Print enabled communication at a distance, which created new opportunities for ambiguity and contested meaning

The comparison also went the other way. Locke, Hume and others explored how material around them might exhibit patterns of the mind. In Méthode nouvelle de dresser des recueils (1685), later published as A New Method of Making Common-Place-Books (1706), Locke added a subject index to the commonplace book format, a genre that had been used for note-taking since antiquity. The addition of topical association via the index, according to one historian, ‘worked … knowledge up into patterns and systems for their instant, motivated use.’ Contemporary writers and printers similarly developed schemes for networked, nonlinear forms of media that might accommodate mental connections. As the popularity of print exploded in the 1700s, writers used cross-references, indexes and, in one of the era’s great works, footnotes. Alexander Pope’s satirical poem The Dunciad (1728), which Marshall McLuhan called the ‘epic of the printed word’, attacked printers for flooding London with cheap pamphlets and single-sheet broadsides. Yet, in its parody, the poem also pushed the print format to a new level of complexity.

The poem follows a group of dunces while the goddess Dulness crowns the new king of nonsense in London, and Pope sprinkles ridiculous versions of his real-life targets throughout the verses. It began as a typical mock-epic satire of the period in which Pope adopts the style of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey to lampoon the trivial failings of his literary rivals. Many of those rivals responded in commentaries and ‘keys’ purporting to decipher the references of the poem. Pope, in turn, added much of that commentary (along with remarks from a fictional editor) as footnotes to the numerous subsequent versions of the poem. In Pope’s final version from 1743, pages often feature only one or two lines of poetry followed by paragraphs of commentary. The book is hypertextual. It sends readers from the verse to notes, to notes on the notes, to various prologues and appendices, and back to the verse. The Dunciad resembles websites filled with hyperlinks and comments.

In the process of perpetually revising his satire, Pope discovered that it is hard to pick out people and objects in the world using print. His friend and fellow satirist, Jonathan Swift, remarked to Pope: ‘I have long observed that 20 miles from London nobody understands hints, initial letters, or town-facts and passages; and in a few years not even those who live in London.’ Unlike oral and manuscript cultures that required close communities, print enabled communication at a distance, which created new opportunities for ambiguity and contested meaning. Print called for new strategies of rhetoric and arrangement. The later iterations of The Dunciad moved toward abstract characters, as Pope emphasised the shape and form of dullness produced by print media. In Book III, the king of Nonsense offers a vision of dullness’s perpetual return in patterns of circular, reflexive motion:

As man’s Maeanders to the vital spring

Roll all their tides, then back their circles bring;

Or whirligigs, twirl’d round by skilful swain,

Suck the thread in, then yield it out again:

All nonsense thus, of old or modern date,

Shall in thee centre, from thee circulate.

‘Maeanders’ refers to a winding river in ancient Greece but, of course, also to the general action of winding. Pope’s poem is filled with images of echoes, reflections and whirlpools that suggest how copies present duller versions of their sources, just as the Moon only hints at the brightness of the Sun. Like water from a spring, The Dunciad’s lines circulated across London in the works of the very writers and printers Pope attacked, and their remarks likewise reappeared in later iterations of his poem. The resulting intertextual network became the new depiction of the burgeoning print world in place of the one initially created by the poem.

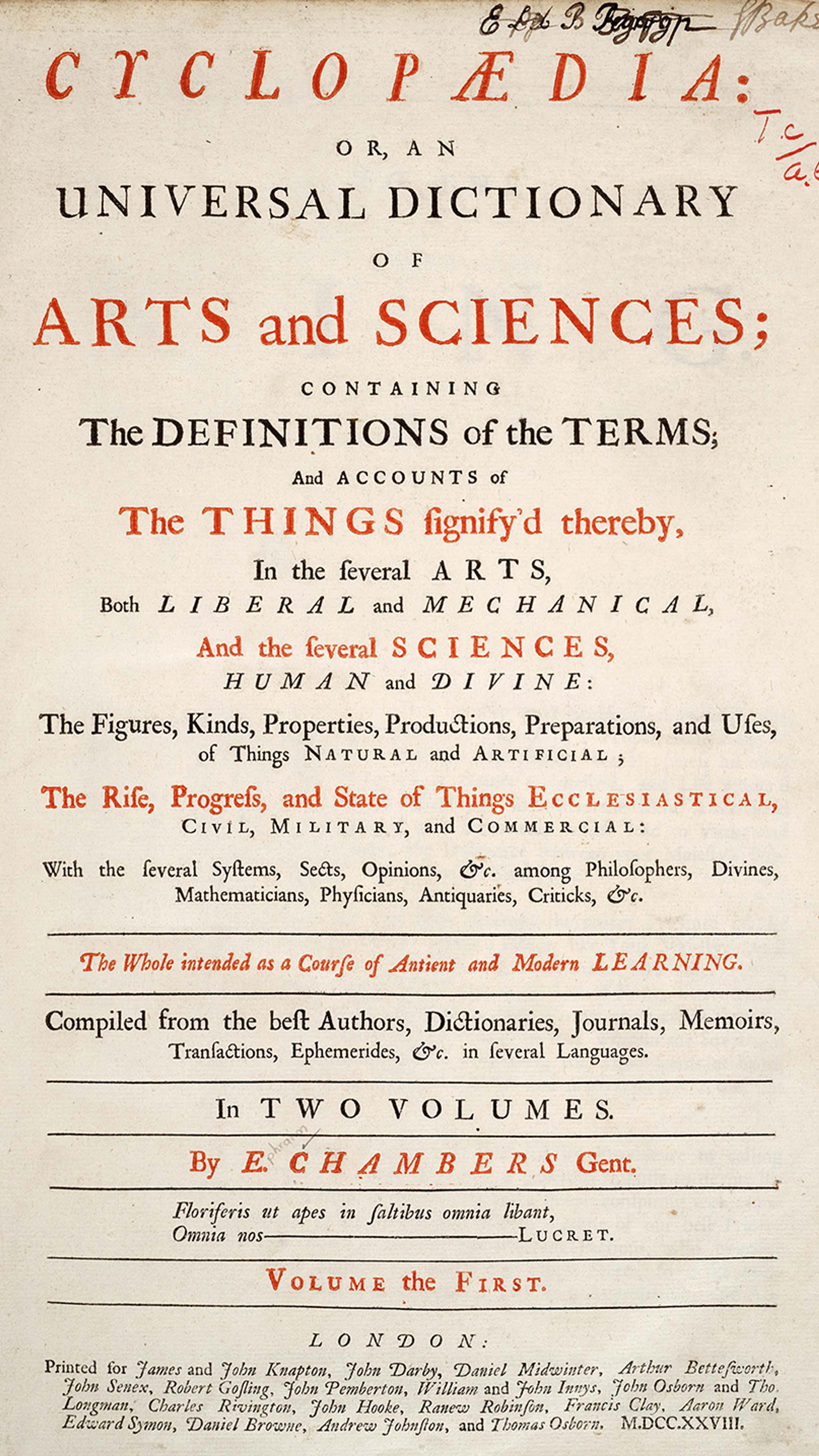

Throughout the period, writers and printers continued to develop ways of arranging language in print that challenged the medium’s typical linear structure. Notable examples include the cross-references and engraved diagrams of the French Encyclopédie (1751-72). The project built upon Ephraim Chambers’s English Cyclopaedia (1728), which explicitly cited the theory of association to explain how the cross-references enabled readers to reconstitute bodies of knowledge from individual entries.

Ephraim Chambers’s Cyclopaedia (1728). Courtesy Wikipedia

A century later, we can observe another shift in how writers understood the relationship between mind and media. James Mill and his son John Stuart Mill laid out comprehensive psychological theories that built upon the 18th-century accounts of association. However, the most lasting impact of associationist theory came from Sigmund Freud’s development of free association as a practice of psychoanalytic therapy. In Associationism and the Literary Imagination (2007), Cairns Craig observes that ‘Freud’s technique of “free association” invites the patient to do exactly what the associationist aesthetics of the empiricist tradition had always insisted readers do in experiencing a poem.’ He cites the late-18th-century essayist Archibald Alison, who described reading a poem as ‘[letting] our fancy be “busied in pursuit of all those trains of thought”’ of the poet.

The emphasis on the association of ideas in early psychology was accompanied by a shift in the medium for observing one’s train of thoughts from print to audio technology. In 1912, Freud compared the role of a psychoanalyst to a telephone receiver:

Just as the receiver converts back into sound waves the electric oscillations in the telephone line which were set up by sound waves, so the doctor’s unconscious is able, from the derivatives of the unconsciousness which are communicated to him, to reconstruct that unconscious, which has determined the patient’s free associations.

Freud’s technique imagined a new context for association in which a therapist would be capable of observing and analysing every link among a patient’s ideas. Like Locke centuries earlier, Freud looked to the media of his time to better understand the human mind.

‘All my computer work has been about expressing and showing interconnection among writings’

Similarly, in the early 20th century, early computer technology offered a new way of capturing the mind at work by combining the textual form of print with the speed of electricity. In the aftermath of the Second World War and the atomic bomb, the scientist Vannevar Bush at MIT explored how technology could enrich human society, rather than destroy it. In an article published in The Atlantic magazine in 1945, he proposed one of the most famous pieces of vapourware in the history of computer technology, a dual-screen microfilm machine that he dubbed the ‘memex’, a portmanteau for ‘memory extender’. His idea was to allow users to create chains of connections, ‘associative trails’, among text from articles and books as well as their own notes, resulting in something like an electronic version of Locke’s commonplace book. Users would append codes to specific passages and notes to create trails that they could retrace to recover their original trains of thought. When Ted Nelson coined the term ‘hypertext’ in an article in 1965, he looked to Bush’s analogue design as a model. Nelson explains hypertext as ‘material interconnected in such a complex way that it could not conveniently be presented or represented on paper.’ The hyper- prefix indicated ‘extension and generality’ as used in mathematics to refer to multidimensional spaces. Nelson imagined a form that could represent the networked shape of thinking without being constrained by the two dimensions of print.

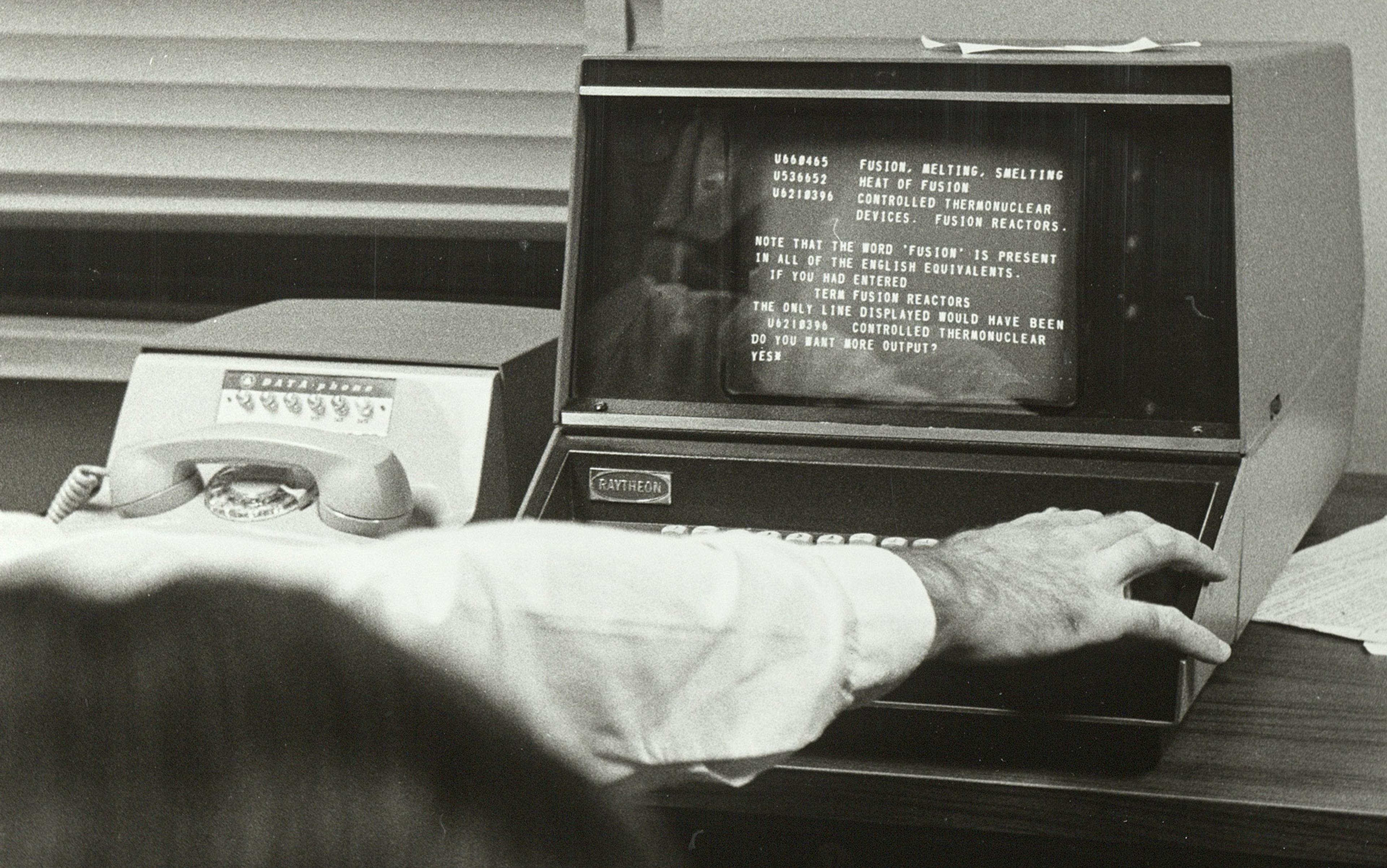

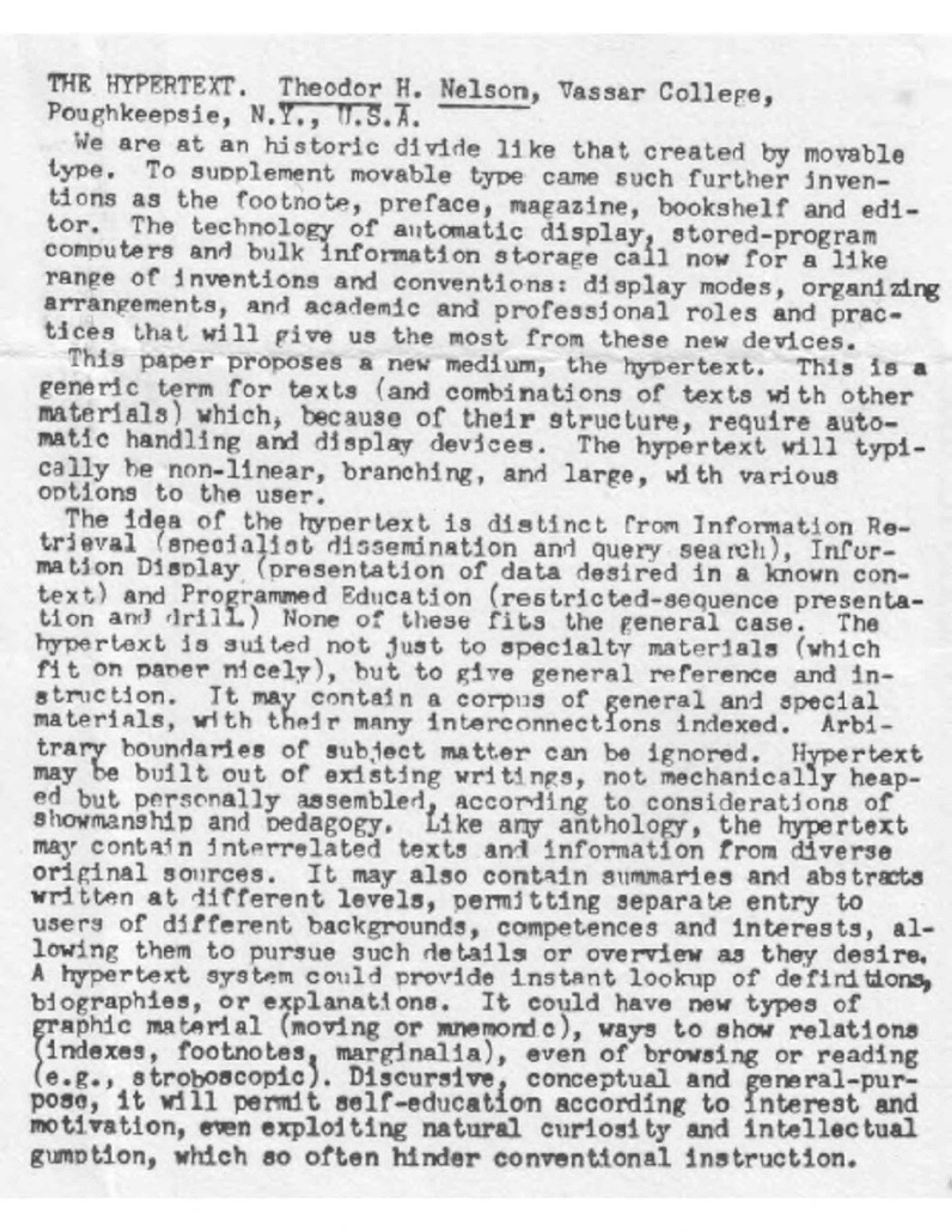

Ted Nelson’s original 1965 article introducing the term ‘hypertext’. Courtesy the Internet Archive/Ted Nelson

Bush and Nelson envisioned media that would allow users to capture their habits of mind – especially the feeling of one idea instantly prompting another one. In Werner Herzog’s documentary about the internet, Lo and Behold (2016), Nelson describes a childhood memory that he credits with inspiring his vision for hypertext:

I was trailing my hand in the water, and I thought about how the water was moving around my fingers, opening on one side, and closing on the other, and that changing system of relationships … and just generalising that to the entire universe that the world is a system of ever-changing relationships and structures, struck me as a vast truth, … and so interconnection and expressing that interconnection has been the centre of all my thinking, and all my computer work has been about expressing and representing and showing interconnection among writings.

Nelson has been widely credited as one of the most influential writers on what the web came to be in the 1990s. However, he has long viewed himself as an outcast. Like Bush, his most ambitious plans for new media were never realised. These include a web browser called Xanadu, which would have accommodated a much more robust model of linking than we’re familiar with. For Nelson, references and, thereby, links should point back to their sources. If you quote a writer in text, then that text should link to the original document, and the reader should be able to view the quoting document and the original side by side, much as Bush envisioned for the layout of the memex. Nelson in a sense imagined a universal version of Pope’s Dunciad – a history of human thought in which the user could trace how lines and phrases moved from one work to another.

In Lo and Behold, Herzog wonders how the internet has changed, and will continue to change, the way we relate to language and the world. At the end of the film, Herzog asks several of his interviewees: ‘Does the internet dream of itself?’ He explains the question as a riff on the remark, attributed to the Prussian war theorist Carl von Clausewitz, that ‘sometimes war dreams of itself’ (although this reference may be apocryphal). War, Clausewitz suggested, can take on a life of its own; it may continue autonomously. One respondent posits that the question hints at the ‘pattern of activity’ that the internet produces without anyone actively designing it. If the printing press, for Pope, seemed to encourage reproduction and dissemination without context, what activity has the internet set in motion, beyond the control of engineers and web designers?

One answer might be connection as embodied by the link. The first actual hypertext systems predated the web by about five years in the early 1980s. As the software historian Matthew Kirschenbaum has observed, early hypertext applications, including Apple’s HyperCard and Eastgate’s Storyspace (both initially released in 1987), were products of the personal computer revolution – not the web. Jay David Bolter and Michael Joyce developed Storyspace as a software for creating hypertext fictions, choose-your-own-adventure-type stories in which the reader decides how to navigate episodes that are connected by links. Joyce used the software to write what is considered the first full-length hypertext fiction, afternoon, a story (1987). He wanted to create ‘a story that changes every time you read it.’ The reader’s path through the nodes and links of the work builds the story’s plot. This work along with Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden (1991) and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995) make up what’s come to be called the ‘Storyspace school’ of hypertext literature.

While these works achieved critical attention in the mid to late 1990s, they haven’t had a lasting impact. However, the software and tools developed to make hypertext fiction possible have remained prevalent. Of course, the most famous hypertext system is the World Wide Web, which advanced upon earlier ones by allowing users to link between sites hosted on servers located around the world. Note-taking and organisation applications also have incorporated hypertext functionality. While Eastgate began as a company for creating hypertext fiction, it later found success with its Tinderbox application, which is a note-taking app that can link notes and media according to topics the user creates. The pattern of activity that digital networks, ranging from the internet to the web, encourage is building connections, the creation of more complex networks.

The key features of the platforms are their abilities to synthesise, summarise and paraphrase information

The work of making connections both among websites and in a person’s own thinking is what AI chatbots are designed to replace. Most discussions of AI are concerned with how soon an AI model will achieve ‘artificial general intelligence’ or at what point AI entities will be able to dictate their own tasks and make their own choices. But a more basic and immediate question is: what pattern of activity do AI platforms currently produce? Does AI dream of itself?

If Pope’s poem floods the reader with voices – from the dunces in the verse to the competing commenters in the footnotes, AI chatbots tend toward the opposite effect. Whether ChatGPT or Google’s Gemini, AI synthesises numerous voices into a flat monotone. The platforms present an opening answer, bulleted lists and concluding summaries. If you ask ChatGPT to describe its voice, it says that it has been trained to answer in a neutral and clear tone. The point of the platform is to sound like no one.

Not all AI-based sites are discarding links though. Perplexity is an AI search platform that purports to rectify the lack of citations provided by ChatGPT and other bots by including footnotes to outside sources. (Arc Search is another platform trying this approach.) The Perplexity platform can link to sources because it is really a hybrid search engine and AI language model. Like all AI chatbots, the LLM produces the responses to users’ questions, but Perplexity combines this response with the results from its search engine, which indexes the web daily. The problem is that, in crawling different websites, Perplexity has been found to plagiarise articles and images with little or no mention of the sources. More fundamentally, though, search has already solved the problem of finding reliable information to users’ queries – at least to the same extent that AI platforms have. Search is incidental to why people use AI chatbots. The key features of the platforms are their abilities to synthesise, summarise and paraphrase information. Their ability to perform these tasks depends upon digesting massive amounts of text and abstracting linguistic patterns from specific sources.

In literary criticism, Cleanth Brooks attacked what he called the ‘heresy of paraphrase’. In The Well-Wrought Urn (1947), he argued that a reader could not sum up a poem by paraphrasing what it ‘says’. Poetry does not work like ordinary language. It is not reducible to its propositional content. Instead, the thing that defines a poem is the interaction between its semantic and non-semantic elements. ‘The structure of a poem resembles that of a ballet or musical composition,’ Brooks contends. ‘It is a pattern of resolutions and balances and harmonisations.’

When we navigate the web via links, we are travelling through the series of connections made by someone else

Despite the different domains, Brooks’s critique echoes ideas expressed by Bush and Nelson in their plans for hypertext systems. Links reveal a creative process that tends to stay hidden in the writer’s mind – the process of connecting ideas and constructing something bigger: arguments, stories and even poems. Bush and Nelson posited that links exhibit natural patterns of thought – the ways the mind leaps from one idea to another – but also patterns of how we read and write. We read a passage, and it sparks connections with five other things we’ve previously encountered. Paraphrase is heretical because it flattens the tensions, ironies and conflicts of poetry. In his theory of hypertext, George Landow describes Bush’s memex methods as ‘poetic machines – machines that work according to analogy and association, machines that capture and create the anarchic brilliance of human imagination.’

We might think about how a user researching a topic navigates the web through search and links. The initial query yields a list of results, some relevant and trustworthy, others less so. The researcher opens several of the links in new tabs. She then skims the most promising page, clicking on embedded links that point to aspects of the topic to be explored in greater detail. As the researcher follows different associative trails, she confronts contradicting and confusing points. She must figure out how to resolve the tensions and conflicts that arise across multiple pages. In a second essay on the memex, Bush describes a similar process accommodated by his linking microfilm desk:

The owner of the memex, let us say, is interested in the origin and properties of the bow and arrow. Specifically he is studying why the short Turkish bow was apparently superior to the English long bow in the skirmishes of the Crusades. He has dozens of possibly pertinent books and articles in his memex. First he runs through an encyclopaedia, finds an interesting but sketchy article, leaves it projected. Next, in a history, he finds another pertinent item, and ties the two together. Thus he goes, building a trail of many items. Occasionally he inserts a comment of his own either linking it into the main trail or joining it, by a side trail, to a particular item.

The web made the investigative process Bush described possible by preserving trails of association. When we navigate the web via links, we are in a sense travelling through the series of connections made by someone else, not unlike reading something they wrote. This is part of what Pope’s Dunciad reveals – the shape of a medium’s form communicates its content, and the interaction between form and content is how it produces meaning. This is of course what Page and Brin recognised in implementing the PageRank algorithm. The links matter as much as the text.

Despite this groundbreaking discovery, on 14 May 2024 at Google’s I/O conference, the company announced plans to move away from their search results interface and toward AI summaries. Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google’s parent company Alphabet, revealed that the conference coincided with the launch of ‘AI Overviews’ in the United States that week. The overviews display a summary response to a query (like ChatGPT’s interface) in place of the traditional list of links to other websites. Google’s head of search, Liz Reid, declared, as if to make her job redundant, let Google ‘do the Googling for you’. Commentators have noted the irony that Google’s AI model, Gemini (like all LLMs), relies on outside websites for training data so that it can return accurate responses, but the chatbot interface would seem to jeopardise its primary data source as users are discouraged from visiting those sites.

Bush proposed the memex as a memory aid that would allow a researcher to retrace trains of thought but also for how it would allow other users to better understand the connections made by earlier thinkers. The web represents the largest assembled repository of collective memory, both in the individual web pages hosted and in the links that allow users to traverse them. How will this repository be supported and developed if users rarely make it past the homepages of Google or ChatGPT?

While the future of the web may seem dark, we might take a cue from Pope’s response to the rise of print. For Pope, the proliferation of print genres and conventions entailed what McLuhan described as ‘the increasing separation of the visual faculty from the interplay with other senses’. Yet despite the uniformity and regularity that print seemed to demand, Pope found a way to capture the interplay of opposing voices in print in a manner that represented the cacophony of 18th-century London’s urban environment. The web may still change in ways that surprise us.