The machine they built is hungry. As far back as 2016, Facebook’s engineers could brag that their creation ‘ingests trillions of data points every day’ and produces ‘more than 6 million predictions per second’. Undoubtedly Facebook’s prediction engines are even more potent now, making relentless conjectures about your brand loyalties, your cravings, the arc of your desires. The company’s core market is what the social psychologist Shoshana Zuboff describes as ‘prediction products’: guesses about the future, assembled from ever-deeper forays into our lives and minds, and sold on to someone who wants to manipulate that future.

Yet Facebook and its peers aren’t the only entities devoting massive resources towards understanding the mechanics of prediction. At precisely the same moment in which the idea of predictive control has risen to dominance within the corporate sphere, it’s also gained a remarkable following within cognitive science. According to an increasingly influential school of neuroscientists, who orient themselves around the idea of the ‘predictive brain’, the essential activity of our most important organ is to produce a constant stream of predictions: predictions about the noises we’ll hear, the sensations we’ll feel, the objects we’ll perceive, the actions we’ll perform and the consequences that will follow. Taken together, these expectations weave the tapestry of our reality – in other words, our guesses about what we’ll see in the world become the world we see. Almost 400 years ago, with the dictum ‘I think, therefore I am,’ René Descartes claimed that cognition was the foundation of the human condition. Today, prediction has taken its place. As the cognitive scientist Anil Seth put it: ‘I predict (myself) therefore I am.’

Somehow, the logic we find animating our bodies is the same one transforming our body politic. The prediction engine – the conceptual tool used by today’s leading brain scientists to understand the deepest essence of our humanity – is also the one wielded by today’s most powerful corporations and governments. How did this happen and what does it mean?

One explanation for this odd convergence emerges from a wider historical tendency: humans have often understood the nervous system in terms of the flourishing technologies of their era, as the scientist and historian Matthew Cobb explained in The Idea of the Brain (2020). Thomas Hobbes, in his book Leviathan (1651), likened human bodies to ‘automata’, ‘[e]ngines that move themselves by springs and wheeles as doth a watch’. What is the heart, Hobbes asked, if not ‘a Spring; and the Nerves, but so many Strings …?’ Similarly, Descartes described animal spirits moving through the nerves according to the same physical properties that animated the hydraulic machines he witnessed on display in the French royal gardens.

The rise of electronic communications systems accelerated this trend. In the middle of the 19th century, the surgeon and chemist Alfred Smee said the brain was made up of batteries and photovoltaic circuits, allowing the nervous system to conduct ‘electro-telegraphic communication’ with the body. Towards the turn of the 20th century, the neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal described the positioning of different neural structures ‘somewhat as a telegraph pole supports the conducting wire’. And, during the First World War, the British Royal Institution Christmas lectures featured the anatomist and anthropologist Arthur Keith, who compared brain cells to operators in a telephonic exchange.

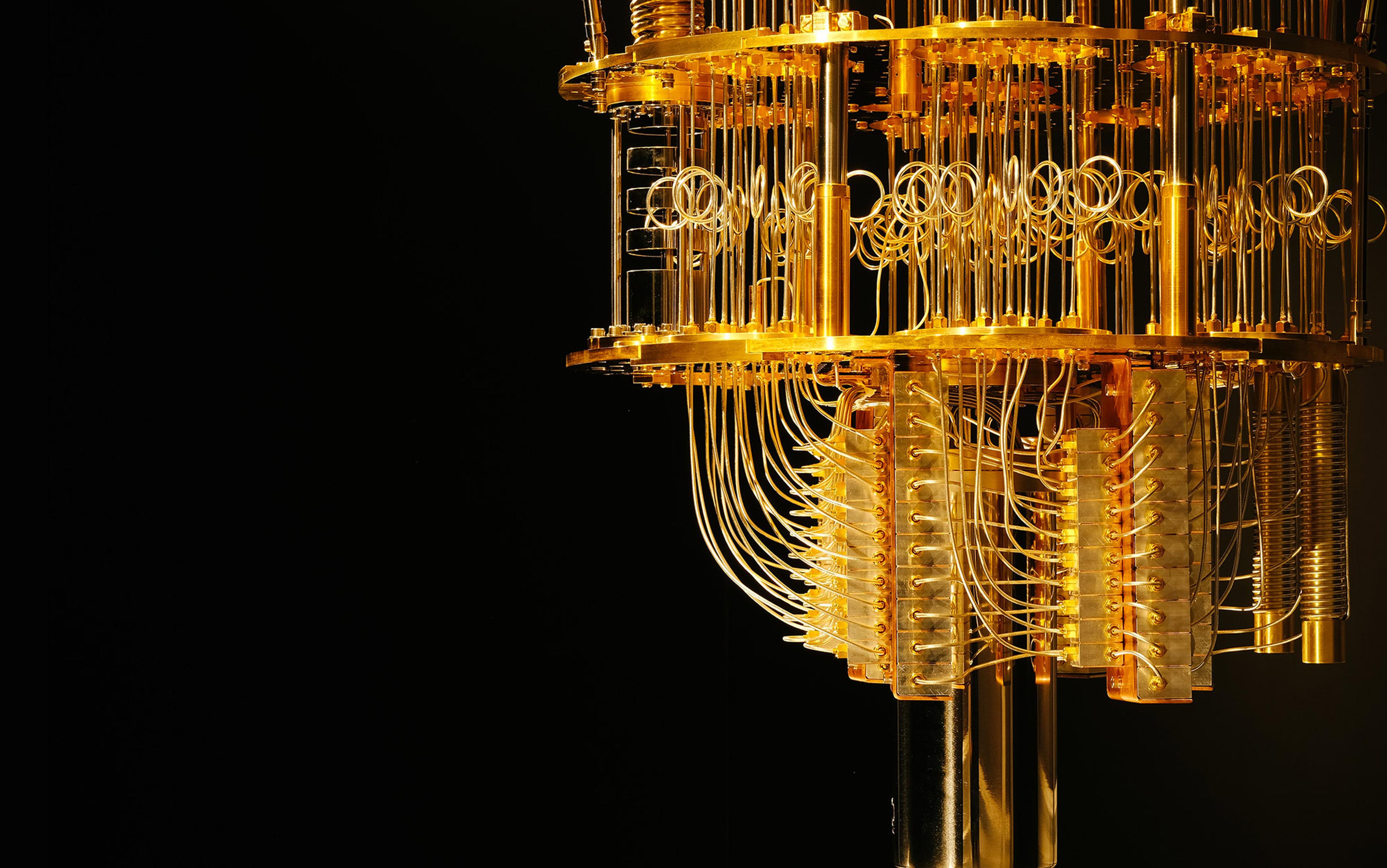

The technologies that have come to dominate many of our lives today are not primarily hydraulic or photovoltaic, or even telephonic or electro-telegraphic. They’re not even computational in any simplistic sense. They are predictive, and their infrastructures construct and constrain behaviour in all spheres of life. The old layers remain – electrical wiring innervates homes and workplaces, and water flows into sinks and showers through plumbing hidden from view. But these infrastructures are now governed by predictive technologies, and they don’t just guide the delivery of materials, but of information. Predictive models construct the feeds we scroll; they autocomplete our texts and emails, prompt us to leave for work on time, and pick out the playlists we listen to on the commute that they’ve plotted out for us. Consequential decisions in law enforcement, military and financial contexts are increasingly influenced by automated assessments spat out by proprietary predictive engines.

These prediction engines have primed us to be receptive to the idea of the predictive brain. So too has the science of psychology itself, which has been concerned since its founding with the prediction and control of human beings. ‘All natural sciences aim at practical prediction and control, and in none of them is this more the case than in psychology today,’ wrote the psychologist William James in ‘A Plea for Psychology as a “Natural Science”’ (1892). In James’s view, psychologists were an asset for their society if and only if they helped that society manage its inhabitants. ‘We live surrounded by an enormous body of persons who are most definitely interested in the control of states of mind,’ James said. ‘What every educator, every jail-warden, every doctor, every clergy-man, every asylum-superintendent, asks of psychology is practical rules.’

‘The enemy pilot was so merged with machinery that (his) human-nonhuman status was blurred’

This vision of the human as fundamentally quantifiable and predictable was cemented by the military struggle of the Second World War. The wartime enemy had long been characterised as a beast or bug fit only to be hunted and exterminated, or as a distant statistic. But there was something new to contend with now: the fighter pilot, the bomber, the missile-launcher. ‘[T]his was an enemy,’ wrote the historian Peter Galison in 1994, ‘at home in the world of strategy, tactics, and manoeuvre, all the while thoroughly inaccessible to us, separated by a gulf of distance, speed, and metal.’ Assisted by technological design, by sensors and processors, attacking this enemy was a risky proposition. Every time you tried to learn more about it, every time you tried to predict its trajectory and kill it, it learned more about you. This enemy, Galison explained, wasn’t some subhuman beast, but ‘a mechanised Enemy Other, generated in the laboratory-based science wars of MIT and a myriad of universities around the United States and Britain’. It was part-human, part-machine – what we might today call a cyborg.

The Allies mobilised every science they could against this enemy, including the behavioural and computer sciences. One of the most influential ideas of the era was a device called the anti-aircraft predictor, designed to simulate an enemy pilot, anticipate his trajectory, and fire. It was the brainchild of Norbert Wiener, an MIT mathematician and scientist. Along with his colleague Julian Bigelow, Wiener developed not just a device but a vision that came to be known as ‘cybernetics’: a way of understanding the world via feedback loops of cause and effect, in which the consequences of an action serve as inputs for further action, allowing for errors to be automatically corrected. As Galison wrote:

the enemy pilot was so merged with machinery that (his) human-nonhuman status was blurred. In fighting this cybernetic enemy, Wiener and his team began to conceive of the Allied antiaircraft operators as resembling the foe, and it was a short step from this elision of the human and the nonhuman in the ally to a blurring of the human-machine boundary in general. The servomechanical enemy became, in the cybernetic vision of the 1940s, the prototype for human physiology and, ultimately, for all of human nature.

During the war, more and more machines and weapons incorporated feedback systems; ‘a host of new machines appeared which acted with powers of self-adjustment and correction never before achieved,’ as the psychiatrist and cyberneticist Ross Ashby said in his book Design for a Brain (1952). These were ‘anti-aircraft guns, rockets, and torpedoes’, and they left soldiers and scientists alike with the impression that machines could act intentionally. Try to throw them off course and, like an enemy pilot in a plane, they’d correct and head for you. As they continued to study feedback processes, Wiener and his colleagues began to see self-regulating machines and intentional human behaviour as one and the same – even explaining biological dynamics (such as homeostasis) and social phenomena, in cybernetic terms. This included the brain – the ‘whole function’ of which, Ashby said, amounted to ‘error-correction’.

The enemy was one type of subject for prediction and control. The consumer was another. John B Watson, a founder of behaviourist psychology in the early 20th century, argued that his discipline’s ‘theoretical goal is the prediction and control of behaviour’ – in service of the needs of ‘the educator, the physician, the jurist, and the businessman’. After being asked to resign from Johns Hopkins University in 1920 in the wake of an extramarital affair, Watson became one of those businessmen himself, joining the advertising agency J Walter Thompson on Madison Avenue.

Before Watson’s arrival, psychology and advertising were worlds apart. Yet after only a few years in Watson’s company, according to his biographer David Cohen, the president of his agency could be found lecturing politicians and businessmen in London that ‘the actions of the human being en masse are just as subject to laws as the physical materials used in manufacturing.’ The early behaviourist view was that humans were input-output machines, bound by the laws of stimulus-response. There was no mind to model, just the inputs and behavioural outputs of predictable animals and consumers. ‘The potential buyer was a kind of machine,’ wrote Cohen. ‘Provide the right stimulus and he will oblige with the right reaction, digging deep into his pocket.’ Advertising agencies would fund their own experiments by researchers such as Watson to test the laws of the consumer-machines that they targeted, rationalising their understandings of phenomena such as habitual product use, targeted messaging and brand loyalty.

Advertising agencies didn’t just apply these principles to sell cereals and cigarettes, but to sell political candidates. The advertising executive Harry Treleaven, for example, spent almost two decades there before leaving to help George H W Bush win his first election in 1966, to the House of Representatives, before going on to help Richard Nixon win the US presidential election in 1968. So many executives at the agency followed the same path that The New York Times would go on to describe it as ‘one of the most prolific suppliers of manpower to the Nixon Administration’.

If software has eaten the world, its predictive engines have digested it, and we are living in the society it spat out

Nixon’s first attempt to become president in 1960 marked a major turn in the corporate enterprise of prediction and control. The life and death of the Simulmatics Corporation, described by the historian Jill Lepore in her book If Then (2020), is in some ways emblematic of this trajectory. When they opened for business in February 1959, just a skip and a jump from J Walter Thompson, the corporation’s founders were preparing to engage in war. Politics was their battleground, Nixon their ‘ferocious adversary’. To defeat such a powerful enemy, the company’s president Edward L Greenfield believed that the Democratic candidate John F Kennedy needed a secret weapon. ‘Modern American politics began with that secret weapon,’ wrote Lepore: predictive simulations, aimed at influencing everything from market behaviour to voting.

To build this weapon – the ‘automatic simulations’ that gave the company its portmanteau name – Simulmatics assembled top scientists from MIT, Johns Hopkins and the Ivy League. According to Lepore, many of the academics ‘had been trained in the science of psychological warfare’. The result was the creation of a ‘voting-behaviour machine, a computer simulation of the 1960 election’, which was ‘one of the largest political-science research projects ever conducted’. The simulation was meant to provide granular predictions about how segments of the population might vote, given their backgrounds and the circumstances of the political campaigns. The company claimed responsibility for JFK’s win, but the president-elect’s representatives denied any relationship to the ‘electronic brain’, as newspapers dubbed it. Simulmatics went on to predict much else: it simulated the economy of Venezuela in 1963 with an aim of short-circuiting a Communist revolution, and became involved in psychological research in Vietnam and efforts to forecast race riots. Soon after, the company was the target of antiwar protests, and filed for bankruptcy by the end of the decade.

Yet Simulmatics’ vision of the world lived on. The founders had faith that, through computer science, anything was possible, and that ‘everything, one day, might be predicted – every human mind simulated and then directed by targeted messages as unerring as missiles’. Today’s globalised predictive corporations have brought this close to reality, harvesting data at a vast scale and appropriating scientific concepts to rationalise their exploitation. Today, the idea that animated the founders of Simulmatics has become, in Lepore’s words:

the mission of nearly every corporation. Collect data. Write code: if/then/else. Detect patterns. Predict behaviour. Direct action. Encourage consumption. Influence elections.

If software has eaten the world, its predictive engines have digested it, and we are living in the society it spat out.

The link between how we understand our biology and how we organise society is a longstanding one, and the association works both ways. When people come together as a collective, the body they comprise is often understood by applying the same concepts and laws we apply to individuals; the words incorporation, corporate, corporation all derive from the Latin root that gives us corporeal, corpus, body. (Organ and organisation are similarly related.) In Leviathan, for example, Hobbes affirmed that society is a sort of body, where

the Soveraignty is an Artificiall Soul, as giving life and motion to the whole body; The Magistrates, and other Officers of Judicature and Execution, artificiall Joynts; Reward and Punishment (by which fastned to the seate of the Soveraignty, every joynt and member is moved to perform his duty) are the Nerves, that do the same in the Body Naturall.

Conversely, we often imposed the logic that governs our society on our own bodies. In Creation: A Philosophical Poem (1712), the physician and poet Richard Blackmore assigned internal animal spirits as the cause of human action and sensation. In Blackmore’s poetry, such spirits were ‘out-guards of the mind’, given orders to patrol the farthest regions of the nervous system, manning their posts at every ‘passage to the senses’. Having kept watch on the ‘frontier’, Blackmore’s ‘watchful sentinels’ returned to the brain only to give their report and receive new orders on the basis of their impressions. The body, for Blackmore, was animated by the same citizens and soldiers as the political world in which he was embedded, as the scholar Jess Keiser has argued.

Today, many neuroscientists exploring the predictive brain deploy contemporary economics as a similar sort of explanatory heuristic. Scientists have come a long way in understanding how ‘spending metabolic money to build complex brains pays dividends in the search for adaptive success’, remarks the philosopher Andy Clark, in a notable review of the predictive brain. The idea of the predictive brain makes sense because it is profitable, metabolically speaking. Similarly, the psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett describes the primary role of the predictive brain as managing a ‘body budget’. In this view, she says, ‘your brain is kind of like the financial sector of a company’, predictively allocating resources, spending energy, speculating, and seeking returns on its investments. For Barrett and her colleagues, stress is like a ‘deficit’ or ‘withdrawal’ from the body budget, while depression is bankruptcy. In Blackmore’s day, the brain was made up of sentries and soldiers, whose collective melancholy became the sadness of the human being they inhabited. Today, instead of soldiers, we imagine the brain as composed of predictive statisticians, whose errors become our neuroses. As the neuroscientist Karl Friston said: ‘[I]f the brain is an inference machine, an organ of statistics, then when it goes wrong, it’ll make the same sorts of mistakes a statistician will make.’

Human beings aren’t pieces of technology, no matter how sophisticated

The strength of this association between predictive economics and brain sciences matters, because – if we aren’t careful – it can encourage us to reduce our fellow humans to mere pieces of machinery. Our brains were never computer processors, as useful as it might have been to imagine them that way every now and then. Nor are they literally prediction engines now and, should it come to pass, they will not be quantum computers. Our bodies aren’t empires that shuttle around sentrymen, nor are they corporations that need to make good on their investments. We aren’t fundamentally consumers to be tricked, enemies to be tracked, or subjects to be predicted and controlled. Whether the arena be scientific research or corporate intelligence, it becomes all too easy for us to slip into adversarial and exploitative framings of the human; as Galison wrote, ‘the associations of cybernetics (and the cyborg) with weapons, oppositional tactics, and the black-box conception of human nature do not so simply melt away.’

How we see ourselves matters. As the feminist scholar Donna Haraway explained, science and technology are ‘human achievements in interaction with the world. But the construction of a natural economy according to capitalist relations, and its appropriation for purposes of reproducing domination, is deep.’ Human beings aren’t pieces of technology, no matter how sophisticated. But by talking about ourselves as such, we acquiesce to the corporations and governments that decide to treat us this way. When the seers of predictive processing hail prediction as the brain’s defining achievement, they risk giving groundless credibility to the systems that automate that act – assigning the patina of intelligence to artificial predictors, no matter how crude or harmful or self-fulfilling their forecasts. They threaten tacitly to legitimise the means by which predictive engines mould and manipulate the human subject and, in turn, they encourage us to fashion ourselves in that image.

Scientists might believe that they are simply building conceptual and mechanical tools for observation and understanding – the telescopes and microscopes of the neuroscientific age. But the tools of observation can be fastened all too easily to the end of a weapon and targeted at masses of people. If predictive systems began as weapons meant to make humans controllable in the field of war and in the market, that gives us extra reason to question those who wield such weapons now. Scientists ought to think very carefully about the dual uses of their theories and interpretations – especially when it comes to ‘re-engineer[ing] science along the lines of platform capitalism’, as the historian and philosopher of science Philip Mirowski has argued.

Seth wrote that ‘perception will always be shaped by functional goals: perceiving the world (and the self) not ‘as it is’, but as it is useful to do so.’ So long as it goes on, we must ask: what is the functional goal of our attempts to scientifically perceive the human mind now? Is it still rooted in a genealogy of prediction and control? Are we shovelling more of ourselves into the mouth of the machine, just to see what it churns out? On whose authority, for whose benefit, and to what end?