It is pale dawn and I am climbing steadily up through wet chilly bracken and across patches of sheep-cropped green grass. As I get higher, long views of peat moorland open around me: up and down, green and gold and beige and brown. I can see no houses (there are only 10 in the surrounding 30 square miles — a widely dispersed community). Occasionally, I catch silver glimpses of the little river or of the single-track unfenced road that struggles up from the coast, through the village seven miles down the valley, over the watershed, and across into the next valley.

I am walking up to Arecleoch, the fourth largest wind farm in Scotland, but for the moment it is hidden by the rising ground in front of me and, briefly at least, the valley feels restored to the empty beauty that brought me here. This walk is part of a three-year struggle to resolve the issue that wind farms have forced upon me: how do we choose between two virtues, between beauty and justice in this instance? Working on the theory that knowledge breeds love and that writing clarifies thought, I keep coming back — physically and in writing — to the wind farms: to why they have created such a conflict and, more crucially, what I can do about it.

I came to live in this upland valley in south-west Scotland because it was so beautiful to me. I recognise that moorland is not always regarded as beautiful and does not fit either of the two culturally favoured aesthetics: the ‘sublime’ (the ferocious wildness of the Highlands, for example) and the ‘lovely’ (the lush green meadows and ancient woodlands of the Cotswolds). You might say the vertical or the horizontal, rather than anything in between. Given the classical association of beauty with symmetry this makes sense, but it is a small palette relative to what is available. Moorland beauty is neither of these; it is too gently curved to be sublime and too austere to be lovely.

I came here to live alone in the huge hush that is both visual and aural and is, to me, exceptionally beautiful

It is the beauty of emptiness in part, of featurelessness. Of course it has ‘features’ really: it has the river, little and playful; there are sea trout, water voles and, they say, otters, although I have never seen one. It has lichen-patched dry stone dykes, many of them now in disrepair, and ruined ghost walls running away up the hillsides. It has greened fields — areas of hard-won, drained and stone-cleared pasture. There is a complicated variety of Neolithic remains — barrows, field systems and standing stones, easily confused with the even older erratic boulders left by the retreating ice of the last glaciation and the newer heaps of stone hauled out of the cultivated fields. There are the farm steadings and the ruined abandoned houses. There is a railway line — a single track that carries the Glasgow trains down to Stranraer where there is no longer a ferry-crossing to Belfast. There is an extensive tangled cat’s cradle of cables.

Inevitably, there is also the forestry, both great swathes of it and a series of ‘pepper-pot plantations’ — the little rectilinear patches of conifers that were such a cunning tax-avoidance wheeze in the 1970s. And all these are in addition to the more subtle ‘natural features’: chunks of extrudant granite; the complex patterning of reed beds, rough grass, bracken, heather, sphagnum moss and sheep-shorn lawn; low clumps of sallows, gnarled old hawthorns, a few neglected coppiced hazels. There is a rich flora, including sheets of orchids, bog asphodel and meadowsweet in season, and some good bird life, although nothing particularly impressive or unique. It does not amount to a site of ‘exceptional natural beauty’ in most people’s book. Nonetheless, I find it heart-wrenchingly beautiful.

The valley does have one notable and distinctive characteristic: it has an exceptional ‘soundscape’. It is not silent in the pure sense that an acoustic chamber, say, or a desert on a windless night are silent. Rather, it is ‘hushed’, and such sound as there is comes from a complex relationship between the various elements of the open, broken land. Like a piece of music compared to a painting, a soundscape is more fluid and varying than a landscape. It is more seasonal, because the migratory birds come and go: the haunting, bubbling call of the curlew is heard only between mid-March and high summer; and the distinctive, almost mechanical ‘chip-chip-chip’ of the invisible grasshopper warbler only between May and July. Because of a phenomenon called ‘attenuation’, the way sounds resonate and carry is different in hot and cold, and in wet and dry, weather. But in the soundscape here, the background noise is so minimal — neither waterfalls nor motorways — that each identifiable sound is distinct and laid onto a sort of murmur or breath which is flowing water and teasing wind, rising, singing, pouring through the day: silence made audible, made musical, if indescribable.

In The Great Animal Orchestra, Bernie Krause defines soundscape by breaking it down into ‘geophony’ — the sounds made by the physical environment (wind, water, etc); ‘biophony’ — the sounds made by animals, birds and insects; and ‘androphony’ — the sounds made by human activities. A soundscape is the interaction and balance of these factors, based on a pretty much correct assumption that there is never absolute silence. Here on the moorland, we have a delicate soundscape that is unusually ‘geophonic’ because we have so much water and wind, but no trees and very little ‘androphony’, even in the distance. To those who listen and care, this is notably pleasing.

The soundscape is important to me, partly because I came here seeking silence in the first place, and is certainly one of the things that makes this place so beautiful. However, I am aware that this is very much a minority concern. Currently our response to nature is almost entirely visual. We barely have a language to discuss the aural. So much is this the case that the Environmental Impact Assessment, which planners now require for many kinds of development, does not take seriously any aesthetic criteria except the visual. The EIA guidelines on noise are deeply confused; changes to the quality (as opposed to the quantity) of sound are never mentioned as grounds for rejecting a proposal. And the source of the sounds seems to be regarded as irrelevant. A chaffinch in your garden, or a waterfall, or beach nearby might be considerably noisier than a motorway a mile off, but still be more pleasing, or less disturbing of the peace.

All this seems quite strange to me, because my sense, anecdotally, is that far more people are moved by and engaged with music than with painting. Yet the very word ‘landscape’ is drawn from visual arts, and we speak only of ‘views’ when describing our natural environment.

In short, I came here to live alone in the huge hush that is both visual and aural and is, to me, exceptionally beautiful. It gives me daily joy. But now I have to plan carefully to get that dose of beauty. Arecleoch wind farm became operational last year. Because of the isolated location, I am, I think, the only person who can see the turbines from an inhabited house. But you cannot miss them from our little lonely road: the massive turbine fins break the smooth curl of the hill-line and inescapably dominate the whole valley, as well as radically changing the atmosphere and appearance of my home. They are disproportionate in scale; they are out of tone with their surroundings — both in colour and in the precision of their lines. Above the gentle moorland, they look brutal. They have been there for more than a year, and they can still stop me in my tracks with grief.

This is just the beginning. Kilgallioch wind farm, less than two miles from Arecleoch and with 99 turbines, is in the final stages of seeking planning permission. Because of its size and because it will cross two regions (as Scottish counties are called), planning permission will come directly from the Scottish Parliament, rather than from the local council, so individual feelings will have even less leverage than usual. The nearest turbine will be barely half a mile from my front door. Mark Hill wind farm (28 turbines, again very visible from our road) opened last year. Last month, the new extension to Artfield Fell wind farm — a further seven turbines, now visible from my garden — started generating. We have just received notification of ‘scoping’ — that is preplanning permission investigations — for another 50 turbines on the opposite side of the valley.

If every turbine now in the system (either operational or formally proposed) is constructed, there will be more than 250 turbines, some of them 145 metres high (almost three times the height of Nelson’s Column) within 10 miles of my house. And although, of course, I won’t be able to see every one of them from my house, there won’t be any direction I can walk in where I will not have to see them. Once the nearer ones are up, I will also have to hear them. This is not necessarily offensive. One of my neighbours likes the sound: she feels that it adds depth and resonance to the soundscape and reminds her of her childhood when she lived beside the sea. But I still feel that, for me, it will be a grotesque change in the context of the hushed atmosphere that I love so much.

I personally find the wind farms ugly. And this leaves me with an internal conflict, because I also believe that they are just.

Although we tend to treat Justice as an objective and unified category, it is scarcely less subjective than Beauty when it comes down to it. I find this very difficult to hold clearly in mind. I grew up with the fixed belief that, for example, there can be no ‘competition’ between forms of oppression, and therefore that justice for some leads to increased justice for all (a sort of ethical version of economic ‘trickle down’).

I have become increasingly aware, though, that this is a ridiculous belief — so ridiculous, in fact, that I am amazed how long it took me to notice. In The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, anyone could see that Articles 18 and 19, while both clearly just, are at least potentially in conflict:

Article 18: Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion … either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

Article 19: Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Forty years later, with the publication of The Satanic Verses by Salman Rushdie in 1988, that rift was plainly exposed. Part of the pain was that no one (including me) seemed to have noticed it beforehand, so absorbed were we in the myth of the indivisible good.

Now I know that Justice, too, is fragmented and partial and subjective. I try to bear this in mind. I am conscious that many people genuinely do not see wind farms as just. On the contrary, for various reasons, they see them either as spurious or even unjust. Some of them do not believe in either climate change or fossil fuel shortage. If they are correct, then wind farms are indeed both pointless and deeply unjust: they are simply a brutal degradation of landscapes and communities by the power companies for the sake of their own bottom line. Others think that ‘fuel supply security’ — that a country needs to be fuel self-sufficient — is a paltry concern or even a distraction in the pursuit of global peace.

Some recognise that the increasingly urgent search for more oil has downsides — including toxic pollution, political instability, habitat destruction, and cultural vulnerability — that are at present bearing unfairly heavily on the poorer nations; but, at the same time, they believe that technology will sort this out efficiently, and also discover sufficient further sources of oil. Many feel that the negative effects on the beauty of the countryside (and, in many cases, its biodiversity, too) simply outweigh all other considerations. Some people are convinced that our international commitments to lowering the carbon footprint were so stupid as to be non-binding, or that the obduracy of emerging economies such as China and India mean that we are no longer bound by such treaties. There are those who hold that we can have no responsibility to those yet unborn.

I find I am living, at alarmingly close quarters, with a moral conflict. All my instincts tell me that this cannot be so. All my thoughts and feelings tell me that it is

Even taken all together, in Scotland at least, these people are a minority. The most recent survey, by Scottish Renewables in 2010, found that 78 per cent of people in Scotland agreed that ‘wind farms are necessary to meet current and future energy needs’. (Up from 74 per cent in 2005, which is interesting because there was a vast increase in the number of turbines visible across the country between the two surveys.) Just over half (52 per cent) disagreed with the statement that they were ‘ugly and a blot on the landscape’, and a slightly larger number (59 per cent) felt that they were necessary to the point that how they looked was irrelevant. Nonetheless, being in a minority does not make wind-farm objectors wrong, especially as there is an inherent problem with democracy and majority rule in that it cannot measure how strongly people feel about something, nor how informed they are on the topic. Presumably some of those questioned might have never even seen a wind farm.

So I am not trying to claim some absolute or idealist Justice here, even if such a thing were to exist. I am saying that I cannot agree with any of these arguments against wind farms. I believe that they are a just and proper way of addressing our power shortfall, of relieving the ecological and social damage suffered by poorer nations who use less fossil fuel, of meeting our international obligations, of protecting the planet and its future from our avaricious consumption of non-renewable resources, and of limiting the damage that human-driven climate change is causing. I cannot even honestly say that there is some special site-specific argument for my moor: the reason why so many power companies want to construct wind farms here is that the conditions are nearly ideal and there are exceptionally few people who will be inconvenienced by it.

I find I am living, at alarmingly close quarters, with a moral conflict. All my instincts tell me that this cannot be so. All my thoughts and feelings tell me that it is. I can sit dithering and hand-wringing (I do a good deal of that anyway). Or I could make a determined choice about which of the two I prioritise; I could decide whether Beauty or Justice is the more important ‘good’, although that would mean fracturing the ideal that all good is ultimately singular. Either way, I have to unpick my ethical inheritance.

I was born in 1950 and brought up, by intelligent parents, in a liberal conservative intellectual tradition. This is not a bad framework for the bright child — offering confidence, security, tolerance, and a benign view of community and independence. Unfortunately, like any political philosophy that is treated as ‘natural’ and therefore goes unexamined, it accumulates myths that are hard to disentangle and sometimes hard even to identify. Among those myths are that the truth will always triumph; that the family is the central bulwark of civilisation; that gender dimorphism makes men behave better towards women; that history is inevitably progressive; that privilege leads directly to a strong sense of responsibility; and that those who ask don’t get.

All these turned out to be untrue, but they are less pervasive, less problematic, than the subtle belief that ‘the good’ is indivisible — that, in the final analysis, there cannot be a conflict between one virtue and another.

One problem with such a pure-minded but absurd assumption is that it leaves one with very little equipment, practical or theoretical, for addressing internal conflicts or making choices between any two things that are both apparently good but incompatible. I find myself convinced that the circle not only should but can be squared.

Of course, I could just consent to live with, or endure, the conflict, but I think I would find that too tiring. The alternative is to decide that one or other of the two elements was not in fact a significant part of the ‘good’ at all.

I find it hard to imagine any society in which Justice was seen as somehow undesirable or was held to exist solely as a psychological rather than an ethical attribute. (I am not talking here about whether or not any particular society is just, but whether its members hold Justice as desirable, regardless of their actual interactions.) One could denigrate Justice as being impossible to deliver, because indeed it seems, as I mentioned above, that justice for person A might well undermine the rights of person B. On the whole, however, the idea that Justice is a key element of ‘the good’ is not only deeply and indelibly embedded in my consciousness, it is also something that I could not seriously or honestly want to change. Tampering with such an aspiration would be to open the floodgates to a ‘might is right’ political ethic that could deliver only horror.

So Beauty would seem a better candidate for such treatment. Modernism, after all, has already launched a partially successful assault on the Romantic notion that there is any connection between Beauty and Truth. And Beauty has certainly been downgraded as a criterion in the arts and is frequently treated as a digression (at best) in the search for the common good. Some people have gone further and suggested that Beauty is actually negative; that when it is observed by power (by the ‘male gaze’, for example), it is dangerous and demeaning to the beautiful, because it objectifies the ‘owner’ of the beauty, and damaging to the not-beautiful as it diminishes their value. Quite how one could apply this to a waterfall, a mathematical proof, a sonnet, a heath milkwort or the Orion Nebula is not clear.

Perhaps a better angle from which to approach the task of amputating Beauty from the whole of the good would be to stress its indefinability, its subjectivity, and its ephemeral nature: as in, ‘not many people think this moor is beautiful’. But this is absurd — ask people whether they want more or less beauty in their lives and the answer is pretty reliably in favour of beauty, whatever it might precisely be to them.

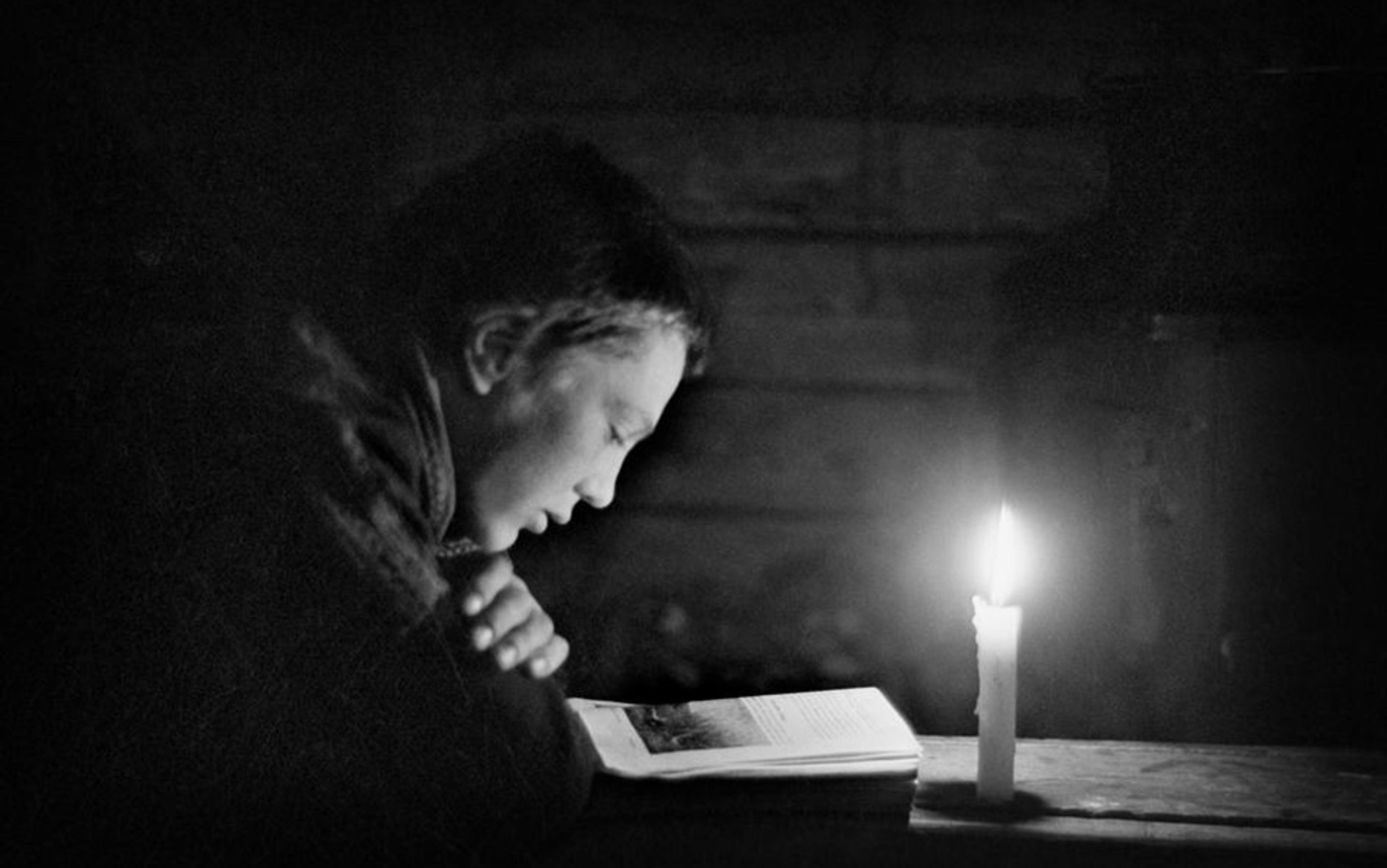

When I first realised the depths of my unease, I struggled to ramp up the emotional intensity of one or other of the two qualities. For a while, I had grim photographs pinned to my walls of suffering children from the Niger Delta, where the damage inflicted by the increasingly desperate search for oil is particularly painful and vivid. I researched mining and drilling accidents. I even attempted for a day or two to live without electrical power and to imagine how that would be for others. I tried to focus on the importance of Justice. Equally, I attempted the reverse: to pursue the human need for Beauty, to increase its ethical importance in my life, to make it intellectually passionate, to give it a wider hold, on my mind as well as my heart. But this ended up feeling both silly and wrong. I find I still want to hold Beauty and Justice, along with other good things, in a whole and healthy balance.

At the moment, I am attempting a rather different approach. I am trying to change the terms of the engagement. I am working on reconstructing my aesthetic taste, so as to find the turbines subjectively beautiful. If I found them lovely and pleasing as well as just, I would have reconsolidated the good and increased my daily joyfulness.

Of course, I could instead work on finding them unjust, but I am too aware of the self-deluded contortions of a certain type of anti-wind farm campaigner (for example, Roger Scruton) who, in order to justify the belief that Beauty is the supreme arbiter, has to marshal a ragbag of unsound arguments to prove that wind farms are unjust and ineffective. But since some of the wind farms already exist within my beloved terrain, I know it would be much pleasanter to live surrounded by positives rather than negatives: beautiful and just seems immeasurably preferable to ugly and unjust.

My new question then is: is it possible, by an act of will, to change one’s aesthetic and emotional response to something?

Some people I have discussed this project with think that it cannot be done, or at least not without psychological mutilation. But I cannot really believe this because I know that my personal aesthetics do change. I know that I now find beautiful things that I found ugly in the 1970s (Rothko’s paintings, John Clare’s poetry and fireworks) and vice versa (Art Nouveau, my ex-husband and miniskirts). I can even think of an example where my idea of beauty was directly affected by morality: when I was young, I thought that fur coats were very lovely — glamorous, sinuous, desirable; later I came to see them as immoral. But, more than that, when I was sorting out my late mother’s clothes, I was almost surprised to notice that I found her furs ugly — lumpy, bulky, shapeless, dull. I had no guilty longing for them at all.

The pleasure of finding new things beautiful, and the sadness of recognising that the erstwhile glory of something has departed, are both quite common experiences, perhaps more so now than before because fashions change so fast. But this is not the same as a deliberate mental campaign to change the way I perceive things. I did not set out to change my mind on these — and many other — judgments. I discovered they had changed for me, sometimes with a sense of startled delight or a feeling of loss.

Suspecting that such an activity is both possible and not perilous to my sanity, I have been experimenting with various ways of making the wind farms look, feel, be, beautiful to me. I am surprised to discover how little this possibility seems to have been explored. For example, given the energy that middle-class parents put into ‘improving’ their children’s aesthetic tastes (making them more like our own, so that they prefer Bach to grunge and Raphael’s Madonnas to Barbie), you might think that the ubiquitous child-rearing manuals would be able to help, but the subject is never mentioned. More directly, it would be useful if the pro-wind farm faction offered some helpful suggestions. But they tend simply to sneer, dismiss, or offer dreary stoical platitudes rather than positive usable suggestions.

Nonetheless, I have evolved a few strategies.

Association is a primary tactic. I am trying to talk to the people who already find them beautiful and avoid all conversations about how ugly they are. In particular, I have been speaking to the sheep farmers, who tend to favour wind power. The Single Payment Scheme (the EU’s subsidy for keeping marginal farming viable) looks due to end in 2015; once it is gone, it is not clear that hill sheep farming can continue. My neighbours tend to see the wind farms as a way, perhaps the only way, of drawing money into the area so that they can go on with their hard, much-loved work. Among other things, they are teaching me that ungrazed and unshepherded the high moor will change anyway. Sheep made the landscape I love; if the sheep go, much of the beauty will go with them; that land will go back to unwalkable scrub and dank bog. The wind farms might turn out to be the guardians and saviours of the landscape. Several of my neighbours have also lived up here for a long time and speak of the various changes that the moor has undergone in the past without losing its loveliness. These conversations really help me.

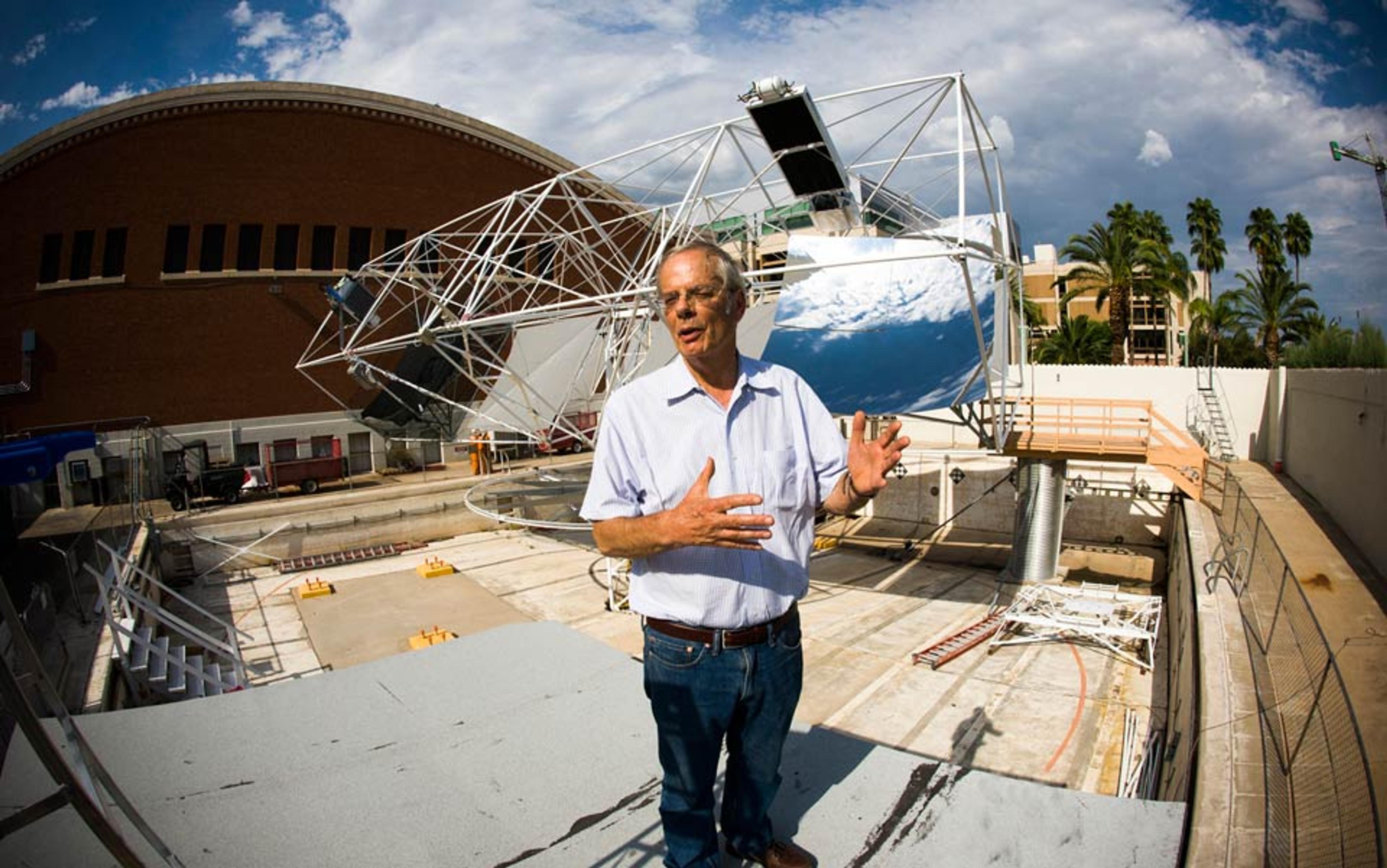

I am realising that knowledge nourishes beauty. The actual workings of a wind turbine are elegantly economical, seriously clever, and both strong and delicate like an athlete. Inside each nacelle (the housing for the generator at the height of the mast: a lovely dancing word itself) is a very beautiful piece of machinery. This is not the beauty of open high moor, but it has a true beauty of its own which I am trying to learn more about.

Language is obviously a key issue: the people who decided to call them ‘wind farms’ were not fools. It is certainly a more attractive name than, say, ‘rural power stations’, particularly when they are located in agricultural countryside. I am rather intrigued by the observation that words drawn from the natural world so often feel more endearing than a technical or contemporary vocabulary. Last year I had a running fight in the local press with someone who wanted to construct an energy-from-waste power generation scheme: he insisted belligerently that it was a ‘plant’; I doggedly reiterated the word ‘incinerator’. You could tell from that alone which side each of us was on, yet both terms are perfectly correct. ‘Rooted’, ‘flowering’ and ‘branching’ feel much lovelier than ‘embedded’, ‘achieving’ and ‘criss-crossed’. So I try to say, think and write ‘wind farm’ rather than ‘power plant’ or ‘generators’, and ‘fins’ rather than ‘blades’ or ‘propellers’ whenever there is a choice. As a society, we do believe this works in other areas; one core strand of the argument behind ‘political correctness’ is that what we name something or someone does affect how we feel about it, as well as how the named experience that naming. I have spent a good deal of my life arguing for inclusive and non-sexist language in that belief; so this should not be too big a step.

Even better, for me, is positive imagery. The ecologist Will Anderson refers to them as my ‘whispering giants’ on the grounds that I love fairy stories and this reference might connect them more easily to other things I find beautiful. And although I do realise it would not be everyone’s way forward, I have also been working on seeing them as an image of the Holy Trinity, like St Patrick’s shamrock. Theologically, this works rather well. The poise, balance and mighty movement of the three fins gathering in and moving the whole sky while the still centre creates power out on the wide space of the moor; and the steady turning grounds my prayers.

Most useful of all, though, has been changing the perspective from which I see them and associating them with things that are already beautiful and joyful for me. I have a nephew, a child still, with true and undisguised enthusiasms. He wanted to see a turbine close up, and so we made them the goal of a long moorland walk. We were actively trying to reach them rather than avoid them. Close to, they are awesome, impressively magnificent, and he was genuinely and bubblingly excited (helped of course by the fact we had no business being there). Looking up at that huge swooping power against a fast wild winter sky, hearing close to the deep song of energy and space, I felt infected by his fierce delight.

Does it work? Maybe. Not quite yet.

But this is why I am walking at dawn up a long boggy slope: I want to see the sunrise turn the turbines into shining silver; I want to see the light glint off them and scatter across the shimmering morning. I want to see it close to and see the long view down the valley which will still be in shadow below me.

In the dawn there are curlews crying invisible. Yesterday it was hot and now, even as I walk, strange patches of very white mist are being exhaled from the curves of the moor like dragons’ breaths. I reach the crest of the hill quite abruptly and, surprisingly near, the Arecleoch turbines are turning slowly, slowly but elegantly; their bases invisible in still smoky mist, their fins silver and catching and refracting the first brightness of the day. It took me several moments of delight to recall that I found them ugly — they seemed enchanted and enchanting.

Beautiful.

Or nearly.

The author is grateful to Elaine Scarry for On Beauty and Being Just (Duckworth, 2006) which addresses some of these issues.

Sara Maitland’s new book, Gossip from the Forest: The Tangled Roots of our Forests and Fairytales, is published by Granta in November