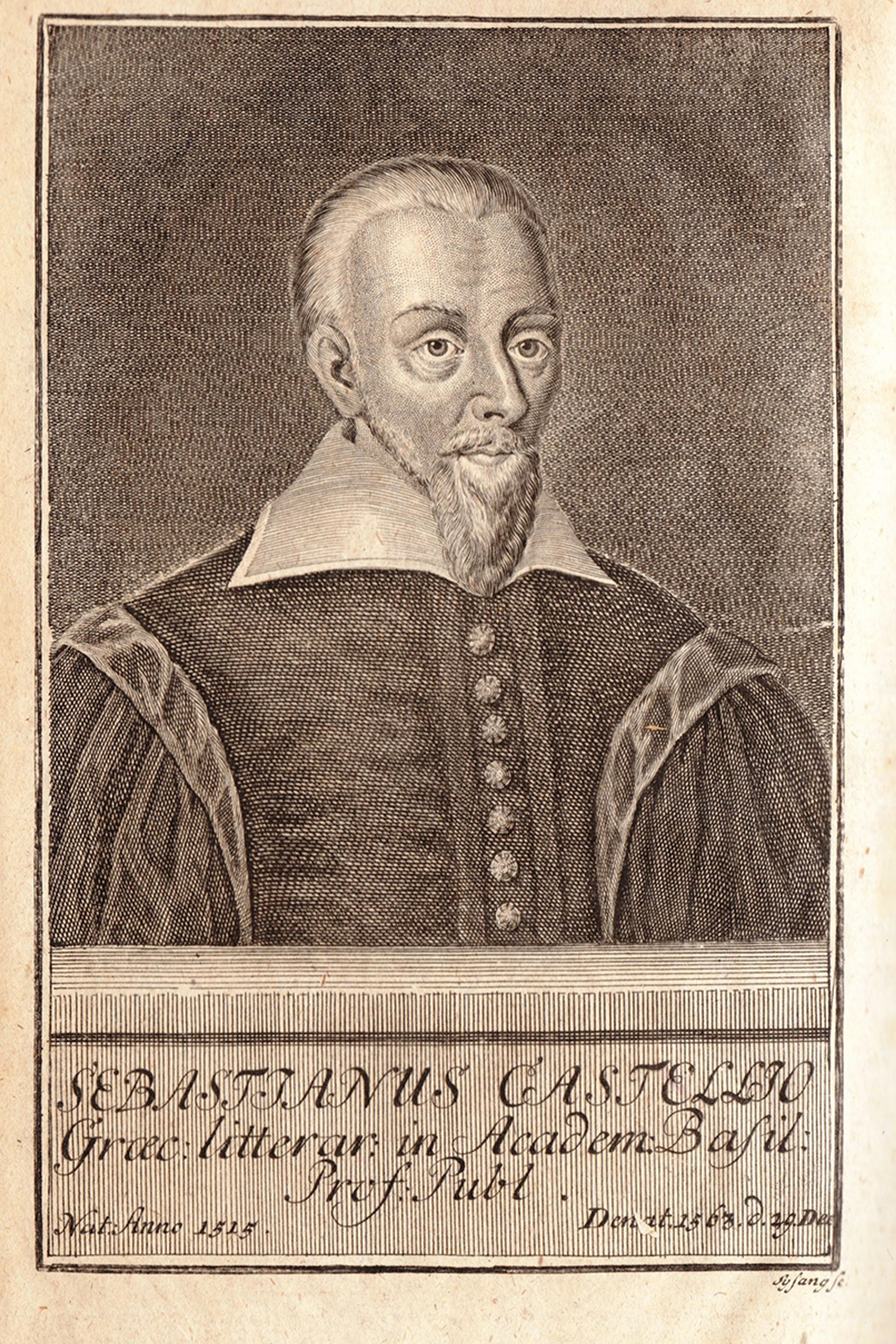

Born in 1515, Sebastian Castellio lived in an age of execution. In terms of judicial killings in Europe, the period between 1500 and 1700 outstripped any era before or after. The new heresies of the Protestant Reformation prompted an initial burst of executions: approximately 5,000 people were put to death for their religious beliefs in the 16th century. This was followed by far deadlier witch hunts, which saw about 50,000 people legally exterminated for witchcraft. Most terrifying for ordinary Christians was the fact that the standards of orthodox thought and behaviour shifted like the sand. One minute, Henry VIII was killing Protestants; the next, Catholics. His daughter Mary earned her ‘bloody’ nickname by executing the very Protestants who had been in favour under her half-brother Edward VI. If we add to the death toll the millions of people who died in the Thirty Years’ War and other Wars of Religion, we see that heresy could be truly lethal.

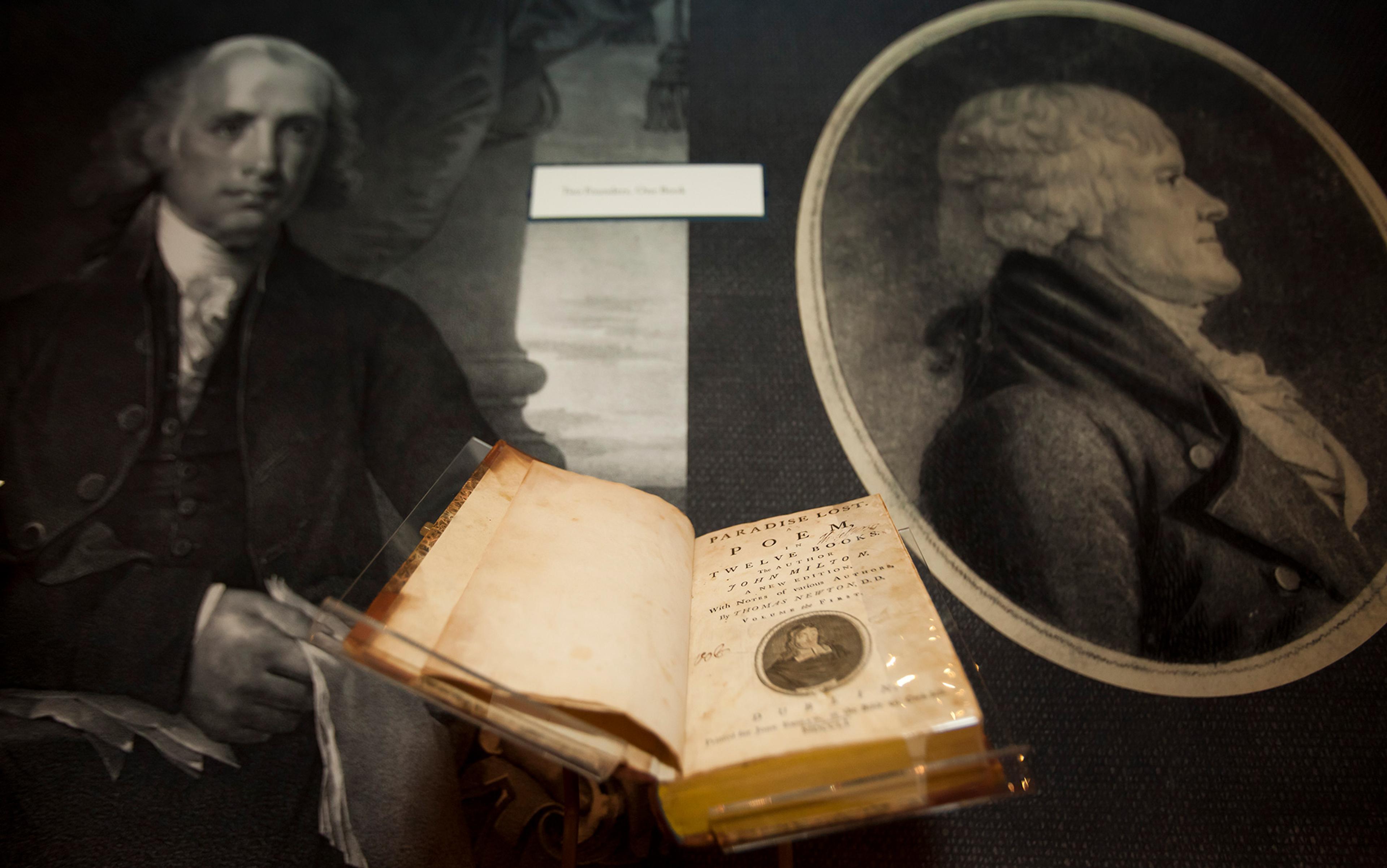

Sebastian Castellio. Courtesy Wikipedia

In the midst of this fear and uncertainty, Castellio, a professor of Greek, stepped back from the dogmatic clashes of the day. Rather than echo the calls for battle, he issued a plea for toleration. His great insight was that everyone was a heretic according to somebody else. Castellio questioned the idea of heresy itself. ‘After a careful investigation into the meaning of the term heretic,’ he wrote, ‘I can discover no more than this, that we regard those as heretics with whom we disagree.’ It was the religious equivalent of the notion introduced a few decades later by Michel de Montaigne that a barbarian is, in essence, someone not like me. To Castellio, being ‘someone with whom we disagree’ was entirely insufficient grounds for being sentenced to death. Today, we take these ideas for granted, but at the time they were revolutionary. In an era with no sense of separation between Church and state, heresy was equivalent to political sedition. Castellio disagreed. He was one of the first to argue that the only way the religiously divided states of Europe could survive was through toleration.

Castellio’s abhorrence at heresy executions led him to question other traditional doctrines and practices within Christianity, including the Bible itself. His views, often developed in opposition to those of his nemesis, John Calvin, would start to grow a liberal branch of Christianity, one that challenged the dogmatic confessions of the churches that emerged from the Reformation and instead championed tolerance, free thinking and reason. Castellio’s ideas eventually won out in the West. But today his name is unknown.

Castellio was an unlikely innovator. He was the son of a farmer, born in the village of Saint-Martin-du-Frêne in France, which at the time lay in the independent duchy of Savoy, about halfway between Lyon and Geneva. In a stunning example of social mobility for the time, he would rise from his peasant origins to become professor of Greek at the University of Basel in the Swiss Confederacy. Though we know little about his formative years, he started his ascent by receiving a humanist education in Lyon, where he demonstrated a gift for learning languages. As a boy, he stomped grapes on his father’s farm; by the age of 23, he was composing Greek verse. He also learned Latin, Hebrew, Italian and some German.

In 1540, at the age of 25, fear of religious persecution drove the newly Protestant Castellio to leave France for the Holy Roman Empire. In Protestant Strasbourg, he met Calvin, who had been exiled from Geneva for too aggressively pushing his ideas for religious reform on the city. Their relationship was initially cordial, and Castellio even lived for a time in Calvin’s house. In 1541, a new group of leaders in Geneva invited Calvin back. He returned, and Castellio joined him as head of the Geneva school. But feelings hardened between the two men when Calvin criticised as inaccurate a French translation of the New Testament that Castellio had drafted. Their relationship soon devolved into open hostility when Calvin thwarted Castellio’s nomination to become one of the city’s pastors. Calvin refused to admit Castellio to the ranks of the pastors because Castellio deviated from Calvin’s views on the biblical book of the Song of Songs and on the interpretation of Christ’s ‘descent into hell’ as confessed in the Apostles’ Creed. It was Castellio’s first lesson in the dangers inherent in dogmatic orthodoxy, whether Protestant or Catholic, and it undoubtedly played a role in leading him to think differently. Catholic persecution had forced him to leave France, now Protestant intransigence drove him from Geneva.

No longer welcome in Geneva, Castellio moved to Basel, where he found work as a poorly paid corrector for a printing press. Castellio used his position at the press to publish several works, including a new translation of the Bible in 1551, rendering it into elegant Latin, as if it had been written by someone like Cicero. His distinctly non-verbatim approach to the translation revealed that he placed more importance on the Bible’s overall message and meaning than on its individual words. Moreover, in his dedicatory letter to the young King Edward VI of England, Castellio revealed his opposition to religious persecution: ‘If someone disagrees with us on a single point of religion,’ he laments, ‘we condemn him and pursue him to the corners of the earth … We exercise cruelty with the sword, flame and water, and exterminate the destitute and defenceless.’

Castellio portrayed executions for heresy as not only cruel and inhumane but positively unchristian

But it was an event in Geneva in 1553 that catalysed Castellio’s thinking. In October that year, the Spaniard Michael Servetus was burned alive for heresy. Servetus was a medical doctor, who was, incidentally, the first European to describe pulmonary circulation. But he also rejected the orthodox doctrine of the trinity – the belief that God is one deity in three co-eternal persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – held by Catholics and Protestants alike. Although he was rejected by almost everyone, Servetus’s antitrinitarian ideas would later influence early Unitarian churches in Poland and eastern Europe. Servetus first published his views in 1531, and the condemnation of those ideas forced him to spend the next two decades underground, living under the assumed name Michel de Villeneuve. His identity was discovered after the publication of the Christian Restitution (1553), a book that revived his heretical views of the trinity. After slipping out of jail to escape the Catholic Inquisition in France, Servetus found his way to Protestant Geneva, where Calvin prompted the city officials to arrest him. The city council found Servetus guilty of heresy and sent him to the stake, sadistically using green wood to slow the flames and consequently increase his suffering.

Calvin defended the death sentence in print, explaining ‘that heretics are rightly to be coerced by the sword.’ He argued that ‘when someone rips religion from its foundations, utters detestable blasphemies against God, leads souls to destruction with impious and pestilent dogmas, and openly defects from the one God and his pure doctrine, it is necessary to apply the ultimate remedy to prevent the deadly poison from spreading further.’ To support his contention, Calvin cited Deuteronomy 13: ‘If anyone secretly entices you …, saying, “Let us go serve other gods” …, you shall surely kill them.’ Most of Calvin’s fellow pastors and theologians at the time agreed. Philipp Melanchthon, Martin Luther’s successor in Wittenberg, praised Calvin for his role in the execution, telling him that the ‘church owes you and posterity will owe you a debt of gratitude. I completely agree with your judgment, and I affirm that your magistrates acted justly when they executed a blasphemer by a judicial process.’ Many of Calvin’s supporters cited Servetus’s ‘blasphemy’ rather than ‘heresy’, for some thought the term carried an even clearer biblical injunction: ‘Whoever blasphemes the name of the Lord shall surely be put to death.’

Castellio disagreed. Recently named professor of Greek at the University of Basel on the strength of his Bible translation and other works, Castellio, together with some friends, published a pseudonymous book entitled Concerning Heretics: Whether They Are to be Persecuted and How They Are to be Treated (1554). Under various assumed names, Castellio portrayed executions for heresy as not only cruel and inhumane but positively unchristian. The executions are bad enough by themselves, he writes:

But a more capital offence is added when this conduct is justified under the robe of Christ and is defended as being in accord with his will, when Satan could not devise anything more repugnant to the nature and will of Christ! … What do you think Christ will do when he comes? Will he commend such things? Will he approve of them?

Instead, Castellio declares: ‘I do not see how we can retain the name of Christian if we do not imitate His clemency and mercy.’

Here we get an early glimpse of the ‘modern Jesus’, the kind and merciful Prince of Peace. This was not a new notion of Castellio’s, but throughout the Middle Ages and Reformation period the image of a merciful Christ stood side by side with that of a vengeful saviour. Before the Crusades, Pope Urban II insisted that ‘Christ commanded’ the military adventure to destroy the ‘vile race’ of the Muslims. Books published by one of Calvin’s printers in Geneva all bore Jesus’ biblical quotation: ‘I have not come to bring peace but a sword.’ But the sword-wielding, vengeful Christ was foreign to Castellio’s conception.

Instead, he saw the execution of Servetus as a profoundly un-Christ-like act, made worse by the fact that it was instigated by Calvin, who was supposed to be one of the lights of the Church. Castellio wrote a second book on toleration, Against Calvin’s Little Book (Contra Libellum Calvini), in which he countered point by point Calvin’s arguments defending the execution of Servetus. He repeatedly pointed out the brutality of executions for heresy in general and argued that it was bloodlust, cruelty and naked ambition for power that drove Calvin to push for Servetus’s execution. Most offensive to Castellio was Calvin’s argument that Servetus’s death was necessary to defend Christian doctrine. As Castellio put it in the best-known line from the treatise: ‘To kill a man is not to defend a doctrine, but to kill a man.’

The conflict over Servetus’s execution set Calvin and Castellio permanently at odds with one another. Calvin couldn’t stand Castellio’s willingness to overlook the threat to religion and public order posed by those who deviated from the true faith. Castellio couldn’t abide Calvin’s rigid dogmatism. For Castellio believed that, properly understood, Christianity is more about moral behaviour than doctrine. The Reformation itself had made that clear to him. After decades of wrangling over doctrine – both between Protestants and Catholics, and among Protestants themselves – it was clear that no sect was ever going to ‘win’.

Castellio believed that it was far more important, therefore, to focus on moral living. ‘We dispute so much about eternal election, predestination, and the trinity,’ he said, ‘insisting on things we can never see and ignoring the things that are right in front of us. From this are born infinite disputes, which result in the bloodshed of the weak and the poor if they don’t agree with us.’ And what are ‘the things that are right in front of us’? The clear moral precepts of Christianity. ‘The precepts of piety are certain: to love God and your neighbour, to love your enemies, to be patient, merciful, and kind, and carry out other similar duties.’ Anyone of any religious sect can practise these things. The way to assess how well a group of Christians lived up to its duties was to judge them by the ‘fruits of the spirit’ listed by St Paul in Galatians 5, namely, ‘love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.’ ‘By such fruits,’ Castellio declared, ‘it is possible to judge which sects are the best, namely those which believe and obey Christ and imitate his life, whether they’re called Papist, Lutheran, Zwinglian, Anabaptist or anything else.’ Indeed, these denominational designations meant nothing to Castellio, who insisted that good Christians may be found in any of them, for ‘they all believe in the same God, in the same Lord and Saviour Christ.’ For Castellio, these were the core messages of the Bible: believing in God and in Jesus as the Saviour, and loving your neighbour as yourself.

After years of fighting with Calvin over toleration, personal attacks and predestination – he utterly rejected Calvin’s idea that God had predestined both those who would be saved and those who would be condemned to eternity in hell – at the end of his life Castellio returned to focus on the Bible. His thoughts on biblical interpretation mark his most radical departure from tradition and most clearly anticipated later liberal Protestantism. For Castellio rejected the idea that the entire Bible was divinely inspired, and taught that one should use the tools of human reason to understand the human authors who produced it.

Christians should not get hung up on exact words but consider the overall ‘tenor’ of the biblical text

Castellio had seen what unquestioning trust in cherrypicked biblical quotations could lead to. Calvin had used it to defend killing heretics. It lay at the root of the interminable debates on how to interpret what happens to the bread and wine of holy communion. Each sect of the Reformation had its favourite verses to justify its own doctrines. Castellio recognised that flinging competing biblical quotations at each other was getting Christians nowhere. ‘Unless some other rule is discovered,’ he declared, ‘I see no way here of attaining concord.’

In an astonishing book for its time, The Art of Doubting and Believing, of Knowing and Not Knowing, Castellio suggested that Christians should not get hung up on exact words and phrases but should consider the overall message and ‘tenor’ of the biblical text. There are things in the Bible, he said, that seem contradictory or absurd. It’s also clear that the biblical authors sometimes made mistakes, and that ‘something may have escaped their memory or judgment.’ Moreover, St Paul himself tells us that he sometimes wrote things from his own judgment, without a command from the Lord. And so, Castellio argued: ‘I don’t see why we attribute to these authors more than they attributed to themselves.’

Rather than consider the entire Bible the inspired word of God, Castellio believed it could be divided into three kinds of texts: revelation/prophecy, knowledge, and instruction. Only the sections he describes as revelation or prophecy are to be understood as the actual word of God. All the other sections – which constitute a large majority of the Bible – are to be understood as the words of humans, which can be evaluated and interpreted in the same way as other ancient texts. And if most of the Bible is a human product, we may use human reason to understand it. Indeed, reason precedes and is more trustworthy than the actual words of Scripture: ‘Reason is, so to speak, the daughter of God … Reason, I say, is a sort of eternal word of God, much older and surer than letters and ceremonies … Reason is a sort of interior and eternal word of truth always speaking.’

Therefore, in any Christian controversy, the place to start is not with the Bible but with reason: ‘Our method will be the following: we start by treating according to reason alone the debated questions. Then we add the authorities taken from Scripture.’ Here we see the method of medieval scholastic theology turned upside down. Whereas the medieval scholastics were engaged with ‘faith seeking understanding’ – starting with the principles of the faith and then trying to understand them using reason – Castellio starts with reason and then adds biblical authorities in support.

Castellio knew that he would be criticised for his ideas: ‘They will cry out that this is blasphemy. The Holy Scriptures, according to them, were written under the divine breath.’ But he realised someone had to deviate from tradition; the old ways were leading to nothing but division and persecution. ‘We must dare something new if we want to help humanity,’ he wrote. ‘We see that advances in the arts, as in other things, are made not by those content with the status quo, but by those who dare to alter and correct those things that have been found defective.’

There was one other key to moving forward, Castellio believed: keeping an open mind and learning how to doubt – hence the title of his book, The Art of Doubting. Even with his new rational approach to the Bible, some things would never be clear. There were many doctrines – for example, predestination, the trinity, and the nature of the Eucharist – over which Christians would always disagree. But that’s OK. The problem is not disagreement but closed minds. ‘A person whose mind is closed holds tenaciously to his opinion and prefers to give the lie to God himself and all the saints and angels if they are on the other side rather than to alter his opinion. Flee this vice,’ Castellio counsels, ‘as you would death itself.’

Death found Castellio before he finished writing The Art of Doubting. He died at the age of 48 in December 1563, five months before Calvin died. He left behind a wife and eight children, including a one-year-old and three others under 10. Calvin and his allies hounded him to the end; at the time of his death, Castellio was under investigation in Basel for allegations of heresy that originated with Calvin’s friend Theodore Beza. Castellio’s final book was not published in full until 1981, but we know it circulated in manuscript after his death. This long delay in publication is one reason for Castellio’s relative obscurity. Censorship and pressure from his enemies meant that several of his works – often the most interesting and radical ones – were not published until many years after his death.

Even so, in certain circles, Castellio has long been appreciated. Michel de Montaigne called him an ‘outstanding’ scholar. John Locke referred to him as ‘so learned a man’ and owned several of his books. Voltaire assessed that he was ‘more learned’ than Calvin. The Enlightenment era saw the flourishing of several of Castellio’s ideas, most notably the primacy of reason. Enlightenment rationalism and advances in science cast deeply into doubt Moses’ authorship of Genesis, the literal truth of the Bible’s creation account and of early biblical history, and the divine inspiration of the Bible. Thomas Chubb, an English deist writing during the 18th century, found a manuscript of Castellio’s Art of Doubting and noted that the ‘excellent Castellio’ was ‘of the same opinion’ as himself regarding the divine inspiration of the Bible. In addition, Enlightenment thinkers downplayed Christian dogma in favour of the faith’s moral precepts. Unlike controversial doctrines, moral precepts such as those from the Ten Commandments not to kill, steal, commit adultery or bear false witness were agreed upon by all and seen as consonant with human reason. Thomas Jefferson rejected miracles and the Christian doctrines based on them but considered Jesus’ teachings ‘the most sublime and benevolent code of morals which has ever been offered to man.’

Taken literally, the Bible can be used to justify slavery and polygamy, among other horrors

By 1835, on the 300th anniversary of the Reformation in Geneva, Castellio’s vision of Christianity had overtaken that of the city’s own far more famous reformer, John Calvin. As the historians Philip Benedict and Sarah Scholl note: ‘By the turn of the 19th century, a liberal, non-dogmatic faith had come to dominate the national church. The all-Protestant organising committee [for the anniversary] consequently spoke of “promoting the grand principles of tolerance which are those of true Protestantism”.’ A ‘liberal, non-dogmatic faith’ grounded in the ‘grand principles of tolerance’ was exactly what Castellio – but decidedly not Calvin – had preached 300 years before.

We should not push the comparison between Castellio and liberal Protestantism too far, however. Castellio knew of few of the scientific advances available to his 19th-century successors. Like everyone else of his time, he was what we would call today a ‘young-Earth creationist’ and even joined in the popular game of trying to date Earth based on the biblical generations (his answer: 5,529 years, 6 months and 10 days). It is also difficult to trace Castellio’s direct influence on later generations of liberal Protestant theologians. It seems that few of them arrived at their ideas by reading Castellio.

But his ideas had prompted an initial reconsideration of long-held religious truths and lingered just below the surface for centuries. More than any direct influence he had on later generations, Castellio’s enduring significance is that he was one of the first to appreciate some of the profound problems caused by the traditional understandings of Christianity, the Bible and, especially, heresy. Taken literally, the Bible can be used – and, in fact, has been used – to justify the practices of slavery and polygamy, the repression of women, the execution of heretics and witches, and the persecution of Jews, among other horrors. The faith can easily be weaponised for political purposes and the exclusion of those who ‘aren’t like us’ or who ‘don’t think like us’. Castellio’s Christianity, by contrast, was short on doctrine and long on openness and morality. That was the message of the Bible for him. Any reading of the Bible or understanding of the faith that did not produce these, he believed, failed to convey the true message of Christianity.