Listen to this essay

28 minute listen

When summer arrived along Florida’s coastline in 2023, marine scientists nervously watched and waited as seawater temperatures steadily increased in unexpected ways. The data streaming in from monitoring devices appeared to show a vast marine heatwave stretching from Cape Canaveral to the farthest reaches of Key West. How hot could it get?

Marine heatwaves are getting longer and more intense, but the heat can sometimes be dispersed by wind, which allows layers of warmer and cooler water to mix. However, in 2023, the winds were weak off the coast of Florida. It was a recipe for disaster. ‘We knew it was going to be bad,’ one marine scientist told me at the time. ‘But we didn’t know just how much.’

It would become Florida’s hottest summer on record. The water in Manatee Bay, near Key Largo, reached 38.4 degrees Celsius, which remains the highest ocean temperature ever recorded. The sheer intensity of the event caught marine scientists off guard. As the heatwave settled into bays and lagoons, corals began to die.

The response needed to be swift. Scientists in the region made plans to remove threatened coral species directly from the reef, mobilising volunteers and boats, and securing aquarium tanks to house collected fragments. This kind of operation is not cheap, which meant these teams needed to quickly apply for funding from national institutions. There was another roadblock, too. Removing corals from Florida’s reefs requires permits. The reef is a highly regulated zone bound by rules designed to prevent overfishing, protect endangered species, and stop harvesting for the illegal aquarium trade. Even corals experiencing a thermal emergency are protected by the law.

But funding and permits tend to move more slowly than marine heatwaves. Although some coral fragments were collected from the reef and their genetic diversity was preserved in land-based facilities through the efforts of Florida’s restoration community, most corals were not so lucky. By the time the money arrived and permission had been granted, it was too late.

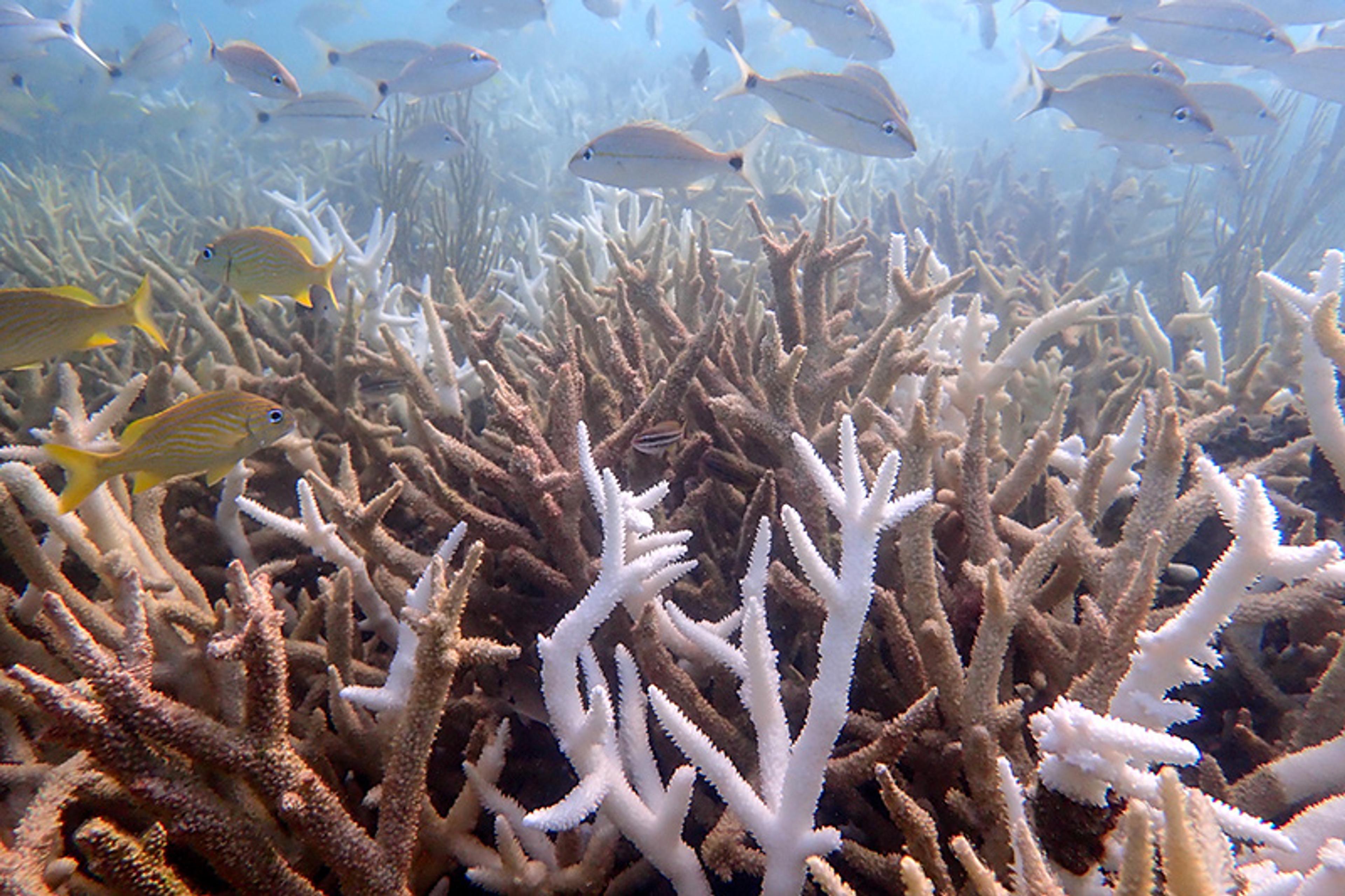

Bleaching has affected 84 per cent of coral reefs in at least 83 countries and territories, and is still unfolding

Liv Liberman was one of the marine scientists who saw the effects of the marine heatwave firsthand. At the time, she was working as a biologist and ecologist at the University of Miami’s Coral Reef Futures Lab, studying the reefs in Florida and testing innovative strategies to increase the survival and fitness of threatened Caribbean corals. When she finally went out to collect fragments, she found that meany of the old colonies that she had worked with and studied for years had died. ‘To see these big, beautiful corals bleach and dissolve before your eyes in the course of a few weeks was incredibly challenging,’ Liberman said. ‘You dedicate your career to this, and then watch it all die despite your best efforts. It makes you question everything.’ In the years that followed, as the heatwaves continued, she would devote herself to coral restoration and conservation work as a director at Revive & Restore, a nonprofit organisation in California spearheading genetics and biotechnology initiatives.

The devastation she witnessed in Florida turned out to be the beginning of the fourth global bleaching event – now the most severe and widespread ever recorded. Already, it has affected 84 per cent of coral reefs in at least 83 countries and territories, and it is still unfolding.

The heat is a problem. But for some scientists hoping to restore coral reefs, the issue is not just the unprecedented temperatures – or even rising emissions. Our blue planet, they say, is being choked by red tape. According to restoration practitioners, some of the greatest threats to the future of corals are the legal frameworks governing how species are handled, relocated, and propagated. This is a view shared by many of those on the frontlines of the climate crisis, who suspect that the law may be hindering the long-term viability of Earth’s ecosystems. Rules and regulations now limit the applications of new genetic technologies and techniques, including the development of hybrid lab-grown species that may be more tolerant of warmer ocean temperatures. As one leading coral scientist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science told me: ‘All the fancy technologies in the world don’t really matter if at the end of the day you are not allowed to apply them.’

Elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata) seen in June 2023 and later in September 2023. Photo courtesy Ross Cunning/Shedd Aquarium

For the past two decades, I’ve been studying the socio-legal and ecological complexities entangled with conservation and restoration projects. During the third global coral bleaching event, which ran from 2014-17, I became interested in the ways that corals were becoming important testing grounds for new approaches to governance. I interviewed dozens of scientists, including Ruth Gates, who was the director of the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology and a pioneer of human-assisted coral evolution. She helped develop the first genetically altered ‘super corals’ that were more tolerant of heat and gave hope that reefs might endure. Through our many conversations, Gates became a key collaborator, who helped me understand the cutting edge of coral science and possible futures for reefs. After she died unexpectedly in 2018, I stepped away from the field.

What drew me back was the Reef Futures conference held in Mexico in December 2024. When I started working with coral restoration experts a decade earlier, their community was tiny and mostly ostracised in the world of established coral conservation, which had been long dominated by older white male scientists from wealthy countries. In those early years, the restorationists were typically younger professionals, many of whom were women emerging from the heatwave trenches. By 2024, this community had grown so much that it was almost unrecognisable: it had become a network of thousands of professionals from around the world, including scientists as well as people from local communities who often turned their lives around to respond to the urgent problems on reefs. The Reef Futures conference was described as ‘the only global symposium focused solely on the interventions and actions necessary to allow coral reefs to thrive into the next century.’ It was here that I first met Liberman, whose presentation caught my attention. When I later sat down and heard her story of the Florida heatwave, I began to grasp how questions of governance were once again entangling with conservation and restoration projects.

International law is poorly suited to the urgency and complexity of the devastation caused by climate change

For many practitioners, the grief of seeing corals die is compounded by the knowledge that some losses could have been prevented if only regulators had acted faster. Permits withheld at critical moments, lengthy review processes, and conflicting jurisdictional requirements have resulted in deep frustrations among coral practitioners toward governments and their regulatory apparatuses. For many coral practitioners, the law appears inadequately prepared to protect reef ecosystems threatened by climate change.

Florida’s reef crisis in the summer of 2023 is a clear example. Various agencies with concurrent authority created layers of review and extensive procedures and so by the time permits were processed, the bleaching had already decimated much of the reef. What should have been an emergency response became a bureaucratic bottleneck.

The problem is especially acute at the international level. Climate change is a global phenomenon, and international law would thus be the most obvious candidate for dealing with it. Tragically, however, international law is poorly suited to handle the urgency and complexity of the devastation caused by climate change. The voluntary nature of international agreements – including the lopsided treaty systems negotiated by unequal member states – have rendered international law woefully ineffective and, at times, even harmful.

As bleaching events continue to unfold and worsen, those who seek to restore reefs are increasingly pointing condemning fingers toward regulators and policymakers for their responses. The scientists I have spoken with have thus been advocating for changes in the law that would remove some of the restrictions, so that they can continue to save corals. From their standpoint, law has become less a tool of protection than a barrier to survival.

But the truth is much more complicated than the practitioners, or the regulators, see it. We are entering a new era, one in which being ‘ready’ – ie, protecting the survival of species – means working across social, institutional, and geographic boundaries in unprecedented ways. If the current laws can’t adequately protect corals, is a new form of governance required?

Ross Cunning, a close colleague of Liberman, has worked on coral conservation for more than a decade. Splitting his time between Caribbean fieldwork and molecular research at Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, Cunning seeks to identify genetic and ecological factors that promote tolerance to increasing temperatures in corals and the symbiotic algae that live inside them (and provide their hosts with energy). For some scientists and conservationists, finding these ‘super corals’ is of primary importance because they may hold the key to reef survival in a warming ocean.

For several weeks in the summer of 2023, water temperatures in the Florida Keys exceeded the historical maximum monthly mean sea-surface temperature by 2.5 degrees – a death sentence for many coral species. So scientists have been seeking corals that can withstand prolonged thermal stress, selectively breeding them, and even using assisted evolution techniques to enhance their resilience.

In 2023, Cunning was looking for potential candidates among the last substantial natural population of staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) in the Dry Tortugas National Park, at the far western end of the Florida reef tract. The Dry Tortugas is mostly open water, with a few small islands, and is known for its extensive coral reefs, which support some of the diverse marine life in the region. To find the most heat-tolerant colonies, Cunning used Shedd’s research vessel as a floating laboratory and performed a range of rapid heat-tolerance tests. He was on the research boat when the heatwave began in June that year.

Members of the Shedd Aquarium dive team monitor corals in 2023. Photo courtesy Gavin Wright/Shedd Aquarium

‘The Dry Tortugas still had a decent-sized natural population of staghorn corals,’ Cunning explained. ‘The idea was to test as many colonies as possible with standardised rapid heat-stress tests to get a metric of how tolerant each colony was relative to the whole population.’ Within a week, his team had tested 200 colonies.

The event set in motion what has been called the ‘functional extinction’ of staghorn corals

At the same time, they sought permission from the National Park Service, the agency that governs access and activities within the Dry Tortugas National Park, to bring back fragments of these corals to nurseries and gene banks as a way of safeguarding their genetic diversity. The need was pressing: very few Dry Tortugas staghorns were represented in existing restoration stocks, making them particularly valuable.

The request from Cunning’s team was denied. According to officials, anything collected in national parks remained government property, requiring formal loan agreements that could not be processed in time.

‘We had applied more than six months in advance,’ Cunning recalled, ‘and, still, it wasn’t enough time.’

He left Florida for Chicago to continue his molecular studies of coral heat tolerance in Shedd’s Microbiome Lab. But by July, as the heatwave intensified, Cunning and his team realised that their project would be meaningless unless they returned to observe how corals were responding to the unfolding heatwave. They scrambled to organise another trip for September, a few weeks after what would become the peak of the heatwave. This time, the Park Service granted permission to take fragments from the reef.

But when the team arrived, the corals were all dead.

‘There were just a few fragments left alive, completely bleached. You could still see a few polyps, a little bit of tissue hanging on for dear life, but we didn’t even attempt to bring them back. We didn’t think they had any chance of surviving. By that time, the genetic diversity of that community was gone.’

The loss was devastating. For Cunning and many other restoration practitioners, the law had not only failed to protect corals but had directly obstructed efforts to save them, condemning massive populations to death by regulatory inaction.

You might be wondering: how serious can it be? Can’t these corals just grow back, like trees in a burned forest?

Scientists who were working in Florida in 2023, including Cunning, now believe that the event set in motion what he and other researchers have called the ‘functional extinction’ of staghorn and other branching Acropora corals. While a few individuals may persist, these species no longer exist in numbers or conditions that allow them to sustain reef ecosystems into the future. They didn’t just die and subsequently begin to recover. Since 2023, they’ve functionally vanished from the Florida Keys, a region they once dominated. Without human intervention, they will likely never regain their important ecological role.

The law can often feel faceless. When it comes to corals in Florida, however, ‘the law’ has a very real representative: Lisa Gregg, the programme and policy coordinator at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC). The agency, authorised by the state constitution, manages wildlife and controls permits for importing and moving corals. Gregg often serves as the public voice of these decisions. Regulators see these decisions as essential safeguards but many scientists find them to be rigid and anachronistic.

A dying thicket of staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) in Dry Tortugas National Park on 11 September 2023, with some branches completely bleached and others having already died. Photo courtesy Shayle Matsuda/Shedd Aquarium

I contacted Gregg in January 2025, asking if she would be willing to discuss her work at the agency with me. She responded immediately and was eager to provide clear explanations – a quality I did not take for granted after working for so long with conservation managers in other contexts. In our conversations, which stretched over many months and included Zoom calls, emails, and group meetings to which she also invited her colleagues at the agency, Gregg emphasised the importance of adhering to established protocols. The FWC, she explained, prohibits corals bred through cross-regional fertilisation (ie, hybrids bred from two colonies growing on entirely different, and sometimes distant, reef systems) from being released into Florida waters. This follows a ‘nearest neighbour’ policy designed to preserve the genetic integrity of local reefs. The rule is intended to avoid what scientists call ‘outbreeding depression’, where crossing genetically distinct populations can reduce the fitness, fertility or survival of an offspring, compared with their parents. Even cross-regional restoration projects that seemed promising have been halted for this reason.

‘We need to address the problems immediately, but we also can’t throw 50 years of genetic theory out the window’

The agency’s geneticist Mike Tringali acknowledged the heavy responsibility of such decisions. ‘To be honest, I don’t always sleep at night,’ he admitted. ‘I was born and raised in Florida and care deeply about the corals. But you can’t panic and do things that are going to have a long-term negative impact. That’s the balance we’re trying to strike: we need to address the problems immediately, but we also can’t throw 50 years of genetic theory out the window just because things are very bad – and there’s no doubt that they are.’

Tringali explained that ‘we need at least a generation of evidence for proof of concept.’ By contrast, he claimed that the restoration scientists ‘sometimes operate on the limited timeline of one grant to the next.’

The stakes behind these permitting decisions are high. A single misstep – such as releasing untested coral strains or moving species across regions – could irreversibly alter reef genetics, spread disease, or collapse entire, already fragile, ecosystems. The law exists to prevent ecological gambles with consequences that could last for generations.

Those attempting to restore corals in Florida have found the logic of the FWC deeply frustrating. Generations of corals can span centuries, they explained, and following such timelines in the face of a rapidly warming ocean did not make any sense. Many have thus argued that strictly adhering to the letter of the law and to precautionary principles, however well-intentioned, has become dangerously restrictive. For scientists promoting, for example, assisted gene flow – a conservation technique that enhances adaptation by moving individuals or genetic material between populations to introduce beneficial traits – these policies often mean missing critical windows for action. In their view, Florida’s cautionary approach risks dooming its reefs to perpetual decline. Still, the Florida regulators insist that rushing could unleash irreversible ecological damage and that the risks of hasty intervention are too great to ignore.

If state laws put brakes on coral restoration actions, international law is often even more restrictive. Its architects are harder to pinpoint, its processes more diffuse and, according to those working in restoration, its frameworks create conditions that are killing corals. One such framework, an international agreement called the Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits, negotiated under the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2010, was designed to ensure fair and equitable sharing of benefits derived from the use of genetic resources, especially between developed and developing countries. In practice, it has produced mixed results.

In 2020, coral research in the Bahamas was abruptly halted when the government, citing the Nagoya Protocol’s requirements, stopped external groups, including scientists, from accessing reefs. For the international coral science community, the shutdown was a severe blow. Its timing was especially painful because the decision came after years of negotiations, just as Florida officials hinted that they might allow the import of Bahama’s corals across the border to strengthen the genetic composition of Florida’s coral populations.

With the Bahamas out of the game, scientists rushed to find alternative reefs. ‘We began trying to find other locations where we could do this from,’ Andrew Baker told me. Baker is a Pew Fellow in Marine Conservation and the director of the Coral Reef Futures Lab at the University of Miami. I met him through Liberman, who was his PhD student. He has spent more than 25 years studying coral reefs and developing strategies to help them survive climate change.

The Tela corals seemed to withstand heat stress far better than their Floridian counterparts

In his search for alternative sites, Baker decided to look upstream to the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef, a 1,000-km coral system that has grown across Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. He was able to establish connections in the Honduran town of Tela, where, among the polluted conditions of the nearby bay, thick stands of elkhorn corals (Acropora palmata) still thrive. The Tela corals seemed to withstand heat stress far better than their Floridian counterparts: they are 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius more thermally tolerant. This is exactly the kind of resilience that might offer hope for Florida’s struggling reefs, but only if the genetics of these tolerant species could find a way to the US.

Securing access to these precious corals was arduous. Baker spent 18 months navigating legal requirements. He hired a local lawyer, drafted applications, and persuaded government agencies that the project would also contribute to Honduran reef resilience.

‘We needed to demonstrate that they could be a source of resilient corals for the region,’ he explained. Eventually, Baker secured Honduran permits, Florida approval, and clearance under CITES, the international convention that regulates exports on certain coral species. Even then, the practical hurdles were daunting.

‘Every country has its own set of rules,’ Baker said. Honduras required veterinary certifications, export licences, and in-country paperwork. Additionally, once the expedition to Tela was mounted, Baker had to work with the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). ‘We needed to file a 3-177 form, which is a Declaration for Importation or Exportation of Fish or Wildlife,’ he told me. ‘Since we have good relations with the USFWS officers at Miami International, this wasn’t too cumbersome.’

Finally, there were the physical challenges of handling an animal that is very sensitive to transportation. Baker described elkhorn species as ‘probably one of the most difficult corals to transport’ – their large, brittle branches break easily and they are extremely sensitive to changes in water conditions, making them prone to stress and disease. For this to work, the team had to minimise transportation time. ‘So we reached out to a Miami-based cargo company to see if they would support it, and they gave us space at no cost on one of their direct flights.’ Baker arranged for the corals to be on the last pallet loaded on the plane and then on the first pallet off the plane. ‘We were up at four in the morning, collected the corals, packed them up, drove for a couple of hours to the airport, then dealt with a whole bunch of paperwork and licences and stuff that had to be dealt with [only] at the airport and [finally] put them on the plane.’

‘It was touch and go the whole time,’ Baker recalled.

The coral juveniles, each just millimetres long, carried the genetic heritage of two reefs more than 1,000 km apart

After an excruciating 16-hour journey, 13 branches of elkhorn coral – each about 40 by 20 centimetres – finally arrived safely in Miami. Baker insisted on splitting them up: six went to the Florida Aquarium, seven to the University of Miami. ‘We didn’t want all our eggs in one basket,’ he said, ‘literally and metaphorically.’ The most difficult step was still ahead: crossbreeding Honduran and Floridian corals to test for heat tolerance.

At the aquarium, staff kept the two populations in separate tanks until spawning. When their timing was right, they carefully crossed eggs and sperm, producing a new generation of hybrid corals. By December 2024, the aquarium housed 570 five-month-old coral juveniles, each just millimetres long but carrying the genetic heritage of two reefs more than 1,000 kilometres apart.

The project was hailed as a breakthrough, but the lesson was sobering. Years of negotiation, stacks of permits, and extraordinary logistical effort had been required to move just 13 fragments across state borders. For Baker, it was a victory of persistence. For many of his colleagues, however, it was proof of how ill-suited existing legal frameworks are to the speed and urgency of ecological collapse.

For every Baker, there are countless scientists whose projects collapse under the weight of bureaucracy.

Baker himself is the first to admit how tenuous his achievement was. He emphasised that importing Honduran corals was possible only because Florida’s FWC had changed their approach in the wake of the losses during the summer of 2023. Since then, Florida has become the only documented legal regime in the world to permit crossbreeding corals from different management zones for the explicit goal of climate resilience. Baker’s ability to bridge science and law – to foster relationships across agencies and to negotiate with regulators – was as critical to the outcome as the science itself.

This raises a difficult question. Who should have the authority to greenlight experimental interventions designed to save corals? Should it be the scientists, who see the urgency firsthand and have the technical expertise? Or the regulators, who are tasked by elected officials with ensuring that desperate actions do not produce unintended ecological consequences?

Neither option is ideal. Self-governance by scientists risks recklessness, public alienation, conflicts of interest, and ethical blind spots. Rigid control by the state risks paralysis, bureaucratic delays, and decisions shaped more by narrow political interest than science.

The clash between scientists and regulators isn’t just a technical dispute – it’s a debate about governance. When decisions about coral survival happen behind closed doors, they concentrate power in two camps: those who want speed, and those who fear risk. But reefs are not abstract ecosystems. They are lifelines for coastal communities that depend on them for food, income and cultural identity. Could including these communities in decision-making ease the deadlock? Local voices might bring practical knowledge and shared accountability, making urgent interventions politically safer and ethically stronger. In short, democratising the science helps bridge the gap between caution and action.

The project of saving these corals cannot be left to either scientists or regulators alone

The way forward is not to sideline one domain in favour of the other, but to build trust and collaboration between them. Law must become more flexible, able to adapt quickly in emergencies. Science must recognise the risks of unchecked intervention. And both must open their processes to local communities and broader publics who also have a stake in the fate of reefs.

Law does not have to be the enemy of corals. It can be their ally, if we allow it to evolve alongside science and the changing climate. Law becomes an ally when it is supported by networks that expand the decision-making process beyond regulators alone and that bring in scientists for expertise and communities for legitimacy. Transdisciplinary networks – of scientists, regulators, community members and the ecosystems themselves – might allow legal frameworks to adapt without sacrificing accountability, thereby bridging that gap between avoiding risk and helping corals.

The project of saving these animals cannot be left to either scientists or regulators alone. It must be democratised, beginning with those who are directly affected, and extending outward to include policymakers, younger generations, and even more-than-human beings. ‘Democratisation’ doesn’t mean abandoning structure or dumping the science. Instead, it means expanding on these forms of management expertise: advisory panels, citizen science programmes, and participatory permitting can bring local knowledge and shared accountability into systems that already exist, making decisions faster, fairer and more resilient.

In the face of extreme and accelerating events, many coral scientists are urging regulators to rethink conservation procedures. The ‘old’ approaches, they argue, are no match for today’s crises. The insistence by regulators on precaution is increasingly viewed as a hindrance – a stance confirmed, in the scientists’ eyes, by the catastrophic fourth global coral bleaching event, which started in 2023 and is still underway.

Some experts who once favoured restraint now find themselves advocating ideas they would have dismissed a decade ago. ‘You know what? Maybe it’s not so crazy to import Pacific corals into the Caribbean,’ one researcher told me. The very notion underscores how drastically the ground has shifted. Interventions once considered reckless are increasingly appearing as necessary strategies for coral survival.

But survival depends on more than just embracing once-feared interventions. It will involve forging transdisciplinary networks that can identify issues before emergencies hit, creating protocols for rapid response, and cultivating resilient collaborations across disciplines and institutions. Only by weaving these worlds together can we hope to respond to climate crises with the speed and coordination that coral survival now requires.

The question is whether we – and by ‘we’ I mean scientists, regulators, communities and all of us who depend on a healthy ocean – can build these relationships in time.