Listen to this essay

22 minute listen

I recently spent an evening trying to convince my father not to go back to Michoacán. I told him it wasn’t a good time. He reminded me that he’s been a naturalised US citizen since the George H W Bush administration. I reported what I’ve seen on the news: people with decades of US residency, with Green Cards and outstanding civic engagement, are being deported, and the rationale seems to have something to do with previous acts of criminality, like shoplifting or parking tickets. I reminded him that, back in the 1990s, he was arrested and charged with assault for an incident at work. ‘I’m afraid,’ I said, that ‘that’s enough to detain you, strip you of your citizenship, and deport you!’ He shrugged. ‘Worse things have happened. Besides, I’m 74 years old. I may die on the way. Nada es seguro.’ Nothing is certain.

I let it be. My sister called me in a panic: ‘Tell him not to go!’

‘It’s no use,’ I said. ‘He’s going. We’ll find out his fate when he tries to come back sometime next year.’ And the waiting game began.

My father’s dismissive attitude used to confuse me. Growing up, I thought he was overly sentimental and melancholic. I was sure that there was something wrong with him. I thought that, maybe, he was depressed. He lived each day like a man who had been betrayed one too many times and was now resigned to a disappointing life.

Now I see how wrong I was. I see now that he was merely reflecting the trials and tribulations of circumstance, that he was a product of a history that had mercilessly exposed him to the truth that a ‘worse thing’ can always happen and that, really and truly, nothing is certain. Now I see that what I thought was dismissiveness was awareness and acceptance of a fundamental fragility and accidentality.

I came to see my father with even more clarity after reading what Mexican philosophers had to say about accidentality and fragility. Mexican philosophers, especially those of the existentialist tradition – what I’ve elsewhere referred to as (M)existentialism – seem to have a person like my father in mind when they talk about what it means to be Mexican. They talk about a type of person who understands or recognises the meaning of the phrase ‘nothing is certain’. This person understands or recognises their nepantla – that they are in between spaces, times, destinations, life and death – and so they recognise their indeterminacy, instability and radical uncertainty, what Mexistentialists call zozobra. In short, they are sure of one thing: that ‘nada es seguro’. That’s my father.

Thinking of my father is one reason why I think it’s important to read Mexistentialism now, or to read it in times of crisis. When we do, not only are we gifted with vocabulary that can help us articulate our current crisis – words like accidentality, zozobra, nepantla and relajo – but it helps us understand how our crises and our philosophies are intimately tied to one another, how historical trauma shapes or informs our perspectives, and why our perspectives matter in the first place. After all, there is a reason why my father thinks that ‘nothing is certain’, and it has nothing to do with something he’s read or something someone’s told him. It has everything to do with the life he’s lived.

Some philosophers get anxious with talk of perspectives or the shaping power of historical events, but in Mexistentialism these are central to understanding ourselves and our world, and especially ourselves in a world in crisis. Undeniably, this is where we find ourselves today: a world in crisis. And by ‘we’, I mean those of us who exist in crisis or under the constant threat of crisis. In this, I follow what the Mexican philosopher Emilio Uranga (1921-88) means when he refers to the ‘we’ that will read and appreciate his philosophical analyses: they are ‘those others that through a thousand accidents of history, of culture or society, have been framed by the catastrophic’. For Uranga, as well as for his contemporaries, those ‘framed by the catastrophic’ are Mexicans and all ‘others’ who, like Mexicans, can identify with a history of oppression, marginalisation and historical violence.

What Uranga couldn’t have foreseen is that the ‘we’ that has been framed by the catastrophic has grown since he wrote those words some 75 years ago. The we whose perspectives are shaped by trauma, violence, persecution and fear has expanded to include many other peoples from across the globe. Closer to home, in the US, it is immigrants or those who look like immigrants who, every day, are framed – shaped, informed, scarred – by betrayal, insecurity and terror, and for whom ‘nothing is certain’ is the only certainty.

For me, reading Mexistentialism in times of crisis has been revealing and empowering. And it can be revealing and empowering for you too. While reminding us that our humanity is fragile and accidental (thus, that nothing is certain), it teaches us that our crises, even if they are framed by the catastrophic, are that only in appearance. Our crises will not destroy us! And we know that our crises will not destroy us because these crises are inscribed in history, and it is history that frames who we are. This is, at least, the lesson of Mexistentialism and its underlying historicism.

Taking a cue from José Ortega y Gasset, Wilhelm Dilthey, Martin Heidegger and others, Mexican philosophers of the mid-20th century come to appropriate ‘historicism’, summarised by the Spanish philosopher Julián Marías in 1967 as the claim that:

the horizon of human life is historical; man is defined by the historical level at which it has been his lot to live; what man has been is an essential component of what he is; he is what he is today precisely because he was other things formerly; the realm of human life includes history.

For Mexistentialists, the truth of historicism is obvious: colonialism, independence, revolution and other historical experiences created the conditions for what they understood, after Ortega, as ‘the horizon of human life’, or as the ‘Mexican circumstance’ – one that, according to Leopoldo Zea’s pioneering work Toward a [Latin] American Philosophy (1942), ‘presents itself always as a problem’. To philosophise is to attempt to solve that problem.

Ultimately, what makes Mexistentialism attractive as a philosophical worldview is that it vindicates or validates the situated, or circumstantial, historical viewpoint or perspective – it empowers it.

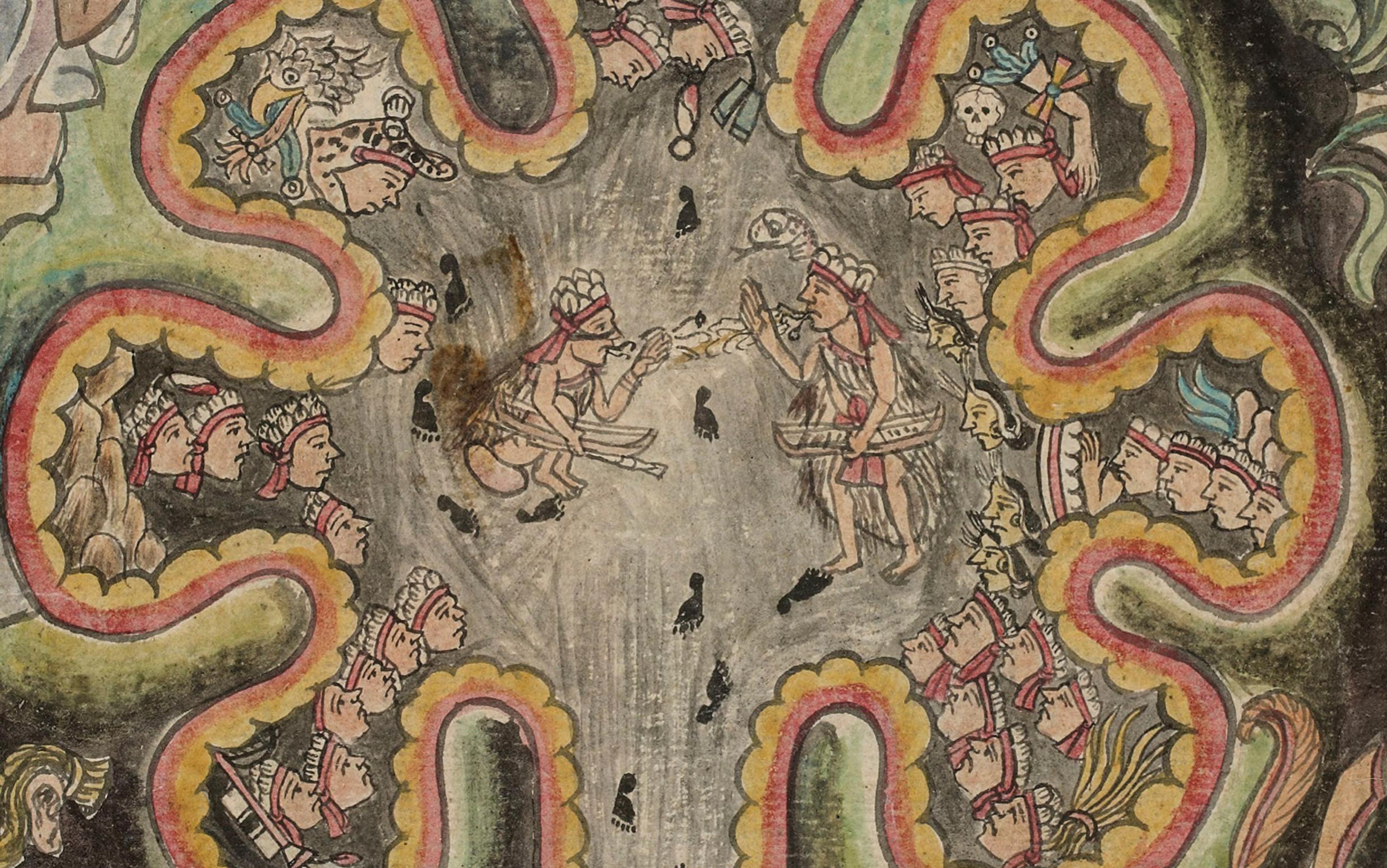

Mexican philosophy, particularly in the mid-20th century, set for itself a difficult task: broadly speaking, its philosophers sought to decipher, for themselves, the meaning of being, existence and freedom within a postcolonial landscape layered with centuries of religious, political and ontological interpretations originally constructed to disempower, oppress and marginalise. For more than 400 years, the West did its best to sediment a certain Eurocentric worldview. This sedimentation manifested in ways of being and doing that were reflections of a non-Mexican being and doing; this became a problem needing a philosophical intervention.

I say this to highlight the idea that Mexican philosophy in general, and Mexistentialism in particular, tends to root itself in history, or culture, or in the ‘circumstance’. Analyses of concepts, ideas or phenomena are often motivated by actual events, by moments in time, by movements and upheavals. The abstract consideration of phenomena or concepts, while not alien to this tradition, is not what defines it. Thus, Mexistentialist philosophers claim to, as it were, ‘take philosophy out to the streets’ and ‘put huaraches on Aristotle’, a dramatic way of saying that their goal is to pull philosophy down to the everyday, to the familiar and concrete, to the lived world and to the lived experience of Mexicans.

A history of immigration, persecution, death and broken promises motivates my father’s pessimistic outlook

Mexistentialist historicism insists that historical events shape how we think and what we think. Mexican history itself – one that is violent, traumatic and catastrophic – demands that philosophers interpret the world in a non-idealistic way, and the effort to put huaraches on Aristotle, or make philosophy intelligible to the common person, is answering that demand. The philosopher Abelardo Villegas attributes such demands to the ‘structure’ of events. The structure of an event is what remains intact after historians exhaust themselves trying to interpret it. This structure is what cannot be interpreted away and the centring of which, ultimately, lends Mexican history its uniqueness and Mexican philosophical insights their value.

Historical forces will inform what is said by philosophy and what is thought as true by folks like my father. A history of violence, conquest, colonialism and revolution motivates Uranga’s philosophy of accidentality, for instance; a history of immigration, persecution, death and broken promises motivates my father’s pessimistic outlook that ‘nothing is certain’. And while these ideas or outlooks are forged in a unique historical experience, they are communicated as valuable lessons for all. Villegas says that the Mexican philosopher will come to ‘offer other peoples … a historical and cultural experience that they may not have.’ This echoes Uranga’s claim in his Analysis of Mexican Being (1952), where he insists that Mexican philosophers ‘have a lesson to teach’, and that this lesson must not be ‘incommunicable’. It will be a lesson translated from the language of experience to the language of philosophy, which means it will be shareable, transferable and potentially empowering. Such empowerment is necessary, especially for those framed by the catastrophic. For them, speaking from their own perspective about their own experience may not be something that has ever been authorised, and, if authorised, deemed of any value.

Yet, if philosophy is informed by history (by the temporal and changeable), then what about objectivity? The most rational among us insist on the supremacy of the objective point of view, defined as the impersonal, detached and ahistorical perspective, because it lends justification to our knowledge, and confidence to our science. A historically informed perspective threatens this supremacy.

For Mexistentialists though, objectivity may not be all that it’s cracked up to be. According to Leopoldo Zea (1912-2004), objectivity is but another remnant of a colonial worldview. Zea referred to the insistence on objectivity as an ‘imperial passion’, that is, an imperialist desire for detachment, depersonalisation and anonymity. On this view, objectivity is an ideological construct useful for those in power (the Imperium), who set it as a metric over what counts as ‘true’ and worth communicating. If a ‘truth’ is not ‘objective’ in this strict sense of the term, then it is discounted as a product of cultural or historical idiosyncrasy – as custom, myth or superstition.

We cannot access the ‘view from nowhere’. We have access only to our own lives, our history and our culture

But discounting truth or knowledge as a cultural and historical idiosyncrasy is a way to invalidate situated, historical perspectives or viewpoints. However, according to philosophers like Zea and Uranga, the situated, historical perspective is the only one available to us, since we are situated and historical ourselves (we can’t be otherwise). We cannot access the ‘view from nowhere’ that Eurocentric views of objectivity (and philosophy) promise. We have access only to our own lives, our history and our culture.

Critics point out that, in the best-case scenario, the historicist approach to philosophy merely reflects those values, beliefs and customs that constitute a culture at a particular time. This view leads the Cuban-born American philosopher Jorge Gracia (1942-2021) to question the possibility of an original, autonomous and genuine Latin American philosophy on the grounds that a cultural foundation to philosophy has no universal applicability and thus lacks philosophical value. Gracia calls this the culturalist approach and argues that it is partly responsible for the delayed arrival of a proper philosophical tradition in Latin America. In Gracia’s estimation, even if culture plays a formative role in the production of knowledge and values, its temporal dimension disqualifies it from being properly philosophical. Historicism is subject to the same indictment.

In his seminal essay ‘Philosophy as Commitment’ (1952), Zea says: ‘Committing ourselves to the universal and the eternal, without making a single concrete commitment, does not commit us to anything.’ While this was written decades before Gracia’s critical remarks on Latin American philosophy, it could serve as a response to that critique. Here, Zea suggests that to seek universality without attending to the concrete (to culture, history, the circumstance and so on) is pointless. Making single concrete commitments is what’s important. And committing oneself to the concrete can take many forms, including trusting in inherited wisdom (‘nothing is certain’) or valuing one’s own perspective.

This brings us to perspectivism. Neither Mexistentialism nor its underlying historicism is to be confused with what we normally call ‘perspectivism’, even if I use words like ‘perspective’ or ‘viewpoint’ to talk about them. Perspectivism itself is rejected by Mexican philosophers on intersubjective grounds. That is, on the grounds that others are always a condition for myself and for what I know. Or that, in paraphrase of Ortega’s famous dictum (‘I am me and my circumstances’), who I am is the product of my engagement with my circumstances, and these are constituted by others in communion and community with myself.

This lack of objectivity is not a shortcoming of Mexican philosophy, but a strength

It wouldn’t be wrong, however, to say that Mexistentialism assures itself on a robust perspectivism, one that becomes robust by linking my perspective (or enfoque) to an array of perspectives that, together, give the appearance of ‘objective’ truth, but that is actually intersubjective truth (truths of multiple subjects). Intersubjective truth reflects or broadcasts a cultural or historical viewpoint; it is not Thomas Nagel’s ‘view from nowhere’ of impartial, or imperial, objectivity.

Again, when Gracia refers to Mexican philosophy as ‘culturalist’, he means it as a critique. A ‘culturalist’ approach to the history of philosophy assumes philosophy to be related in some intimate way to culture and its crises – with how to address these or how to overcome them or deal with them. Gracia calls it this to highlight its lack of objectivity (and distance it from genuine philosophy). But this lack is not a shortcoming of Mexican philosophy, but a strength. It is an affirmation of the subjective point of view. Moreover, if the perspectival array (or the culturalist standpoint) gives us a faithful picture of the reality or the situation in which we find ourselves, or if it truly reflects how the world is for us, then I don’t see why it shouldn’t be that which motivates our philosophies.

A careless reader may conclude that what’s really going on here is that Mexican philosophers simply do not want to bother distancing truth from context, or that they are simply ignorant of the philosophical requirements of objectivity, and thus of genuine philosophy. This, of course, is not the case. Mexican philosophers are neither unbothered by nor ignorant of what the West has deemed ‘genuine philosophy’; they know its history and ideological demands well. Rather, they make the subjective point of view together with culture and history the main ingredients in their philosophising because, in doing so, they validate those elements, themselves, and their philosophy.

And there are lessons here. Mexistentialism has something to teach us. It teaches us that historical experience is necessary for self-understanding and, more importantly, that historical consciousness is essential for framing those questions that should matter to our philosophy. With these lessons we can get on with the task of recognising, articulating and vindicating other philosophical interventions throughout the globe. We can get on with the task of a global philosophy.

I say this because I suspect that an anxiety keeping academic philosophers from embracing global philosophical traditions is the thought that, in doing so, they would be embracing something like cultural relativism in philosophy. When it comes to Mexican philosophy, I’ve come to think that the anxiety that it offers merely a determinate cultural perspective is grounded on confusing historicism for perspectivism as a relativistic, solipsistic doctrine that closes off roads to intercommunication. But for Mexistentialists in particular, cultural perspectives are not closed, relativistic or solipsistic, but historically informed articulations of lived experience that transcend themselves whenever they’re shared.

Mexican philosophers chose to retain their difference by linking their philosophy to their history

What Uranga, Zea and Villegas make clear is that the philosophical point of view (or viewpoint, or perspective) offered by Mexican philosophy is not relativistic, but historical, cultural and circumstantial. And that if a perspective is all these things, then it’s worth communicating and sharing. More importantly, these philosophers assure us that there’s nothing abstract or mysterious about these shareable, or transcendental, truths. They are formed by the pressures of history and experience, and can be recognised by anyone who recognises those pressures. When these perspectives or truths are brought together, they paint an outline of the human condition that is familiar, yet rough and always incomplete. However, only when these cultural, historical or circumstantial truths are linked together in an array of truths can we talk of ‘global philosophy’ – if we can talk about such things at all without saying more than what we are justified in saying.

But why not just do philosophy as the West has taught us to do philosophy, that is, without reference to history or circumstance – sub specie aeternitatis (from an eternal perspective). The answer to this is very straightforward and related to what is known as a philosophical ‘double bind’: Mexican philosophers can either affirm an authentic philosophical identity aligned with the particularity of Mexican difference, and thus firmly within the bounds of Mexican history as a source of meaning and value, or insist on philosophy as an ahistorical expression of a human sameness, something that requires the transcendence of that history and those circumstances and thus a transcendence of difference. It’s a double bind because if it chooses to retain its historical difference, then it risks not being philosophical in the Western sense; if it chooses to be philosophical in the Western sense, then it risks erasing its difference. Mexican philosophers chose to retain their difference by linking their philosophy to their history.

My father’s attitude to certainty is not his alone. It is a worldview forged in the crucible of history and experience, and articulated for us by Mexican existentialists with concepts like accidentality, zozobra, relajo and nepantla – concepts that capture the contingency and vulnerability of human life. In pronouncing that ‘nothing is certain’, my father is merely echoing the teachings of experience, while simultaneously preparing himself for what may come. That he easily channels philosophers in critical life moments does not surprise me. After all, he is a product of a historical circumstance that is not unlike those of the philosophers who came before him: although catastrophic, it is powerful and empowering. And we could say the same about the great majority of us, Mexican or not: we are products of a history that, while it may be traumatic and painful, can also be powerful and empowering.

I myself cannot be an optimist for the same reasons that my father chose to take his chances with immigration enforcement. Recent events have made it abundantly clear that my citizenship offers little certainty and security, even though I was born in the US and have lived here most of my life. If the political winds continue to blow in the direction in which they are currently blowing, I may end up living with my father in Michoacán, exiled from my home, a victim of history and its many catastrophes. But I know only what history has taught me. And history has taught me that my father’s right: nada es seguro. And so we persist.