If you are interested in the themes of this Essay, please join us at Sophia Club New York on 13 February for our live event ‘How to live well in a slippery world’, where we’ll delve into the world of Aztec philosophy.

I gripped the steering wheel as the car started to slide. Slowly, slowly I manoeuvred the tyres back into the sandy tracks of what they called the road. I had set out from the tiny desert town of Cuba in northwestern New Mexico and had left the highway behind me where the sign pointed toward Chaco Canyon. The owner of the ranch where I was staying had told me that she had heard the road to Chaco was open today and I had nodded cheerfully. I realised now that I should have wondered why it might not be.

The loose sandy track was from another century. If it had been raining, it would certainly have sent me spinning off the edge. As it was, the car managed to hold on. Just barely. Hours later, I lurched through the entrance of the Chaco Culture National Historical Park. It was 104 degrees Fahrenheit outside of the car, and almost blindingly bright. I tried to let my eyes adjust, determined to manage without the sunglasses or hats that hadn’t existed when ancient Puebloan peoples built this place 1,000 years ago. I lasted 10 minutes, then put on the shades.

Soon, armed with food and water and a map, I set out. I was excited. I was entering a world I had not known existed. No book, no map and no website had been able to prepare me for this hidden land. The segment of the San Juan River that had once cut into rock and forged the canyon where I stood still existed as a trickle. About a quarter of a mile on either side of the wash rose the dramatic cliff walls of the canyon, and scattered along the base of those walls were about 20 ancient structures. It was hard to tell what they were without going closer.

I walked along the path to Pueblo Bonito. Heat-seared grasses swayed in the breeze. Part of the rock-built structure rose several stories. I entered a sort of alley between the great wall of the building and the wall of the cliff. Looking down, I saw a shard of black-and-white pottery: I was standing, I supposed, on top of an ancient garbage dump. In the silence, insects whirred, making the same sound heard by the person who had left the pot here, something like 40 generations ago.

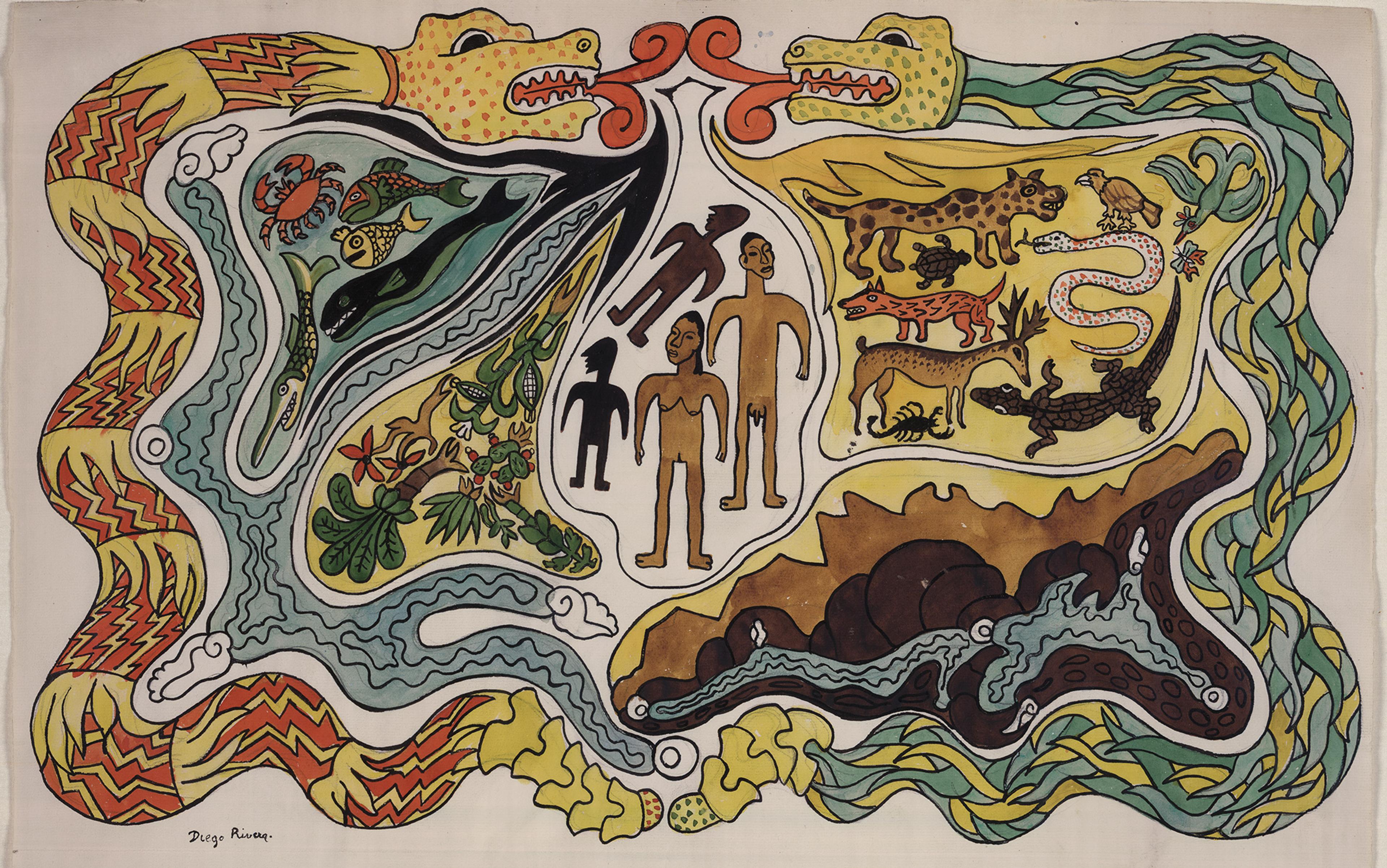

I entered the building and wandered from room to room. The chambers were smallest of all towards the very back – the part they had built first, in about the year 850, and retained as sacred space when they built in later centuries, peaking in about 1050. The oldest part was where archaeologists had found the people’s greatest treasures, carefully transported from far-off Mexico. The bits of polished jade and stunning quetzal feathers had come from Central America, via a vast trade network dominated by cities in Mexico such as the fabled Teotihuacan. There, far to the south, the corn-and-beans agricultural complex was much older than it was here, and it had engendered a wealthy civilisation, home to pyramids, hot chocolate and pictographic writing.

Between the 900s and the 1200s, hearing rumours of wealth south of here, some of the denizens of the desert that surrounded me had chosen to migrate to the central valley of Mexico and join the farmers famous for their successes. The culture that the two groups created between them would later be called ‘Aztec’ (though that was not a word they themselves ever used).

As a scholar and teacher of Mesoamerican history and culture, I had been reading Aztec writings for years. But I had never visited any archaeological site that felt like it was truly theirs. Mexico City was built directly on top of their capital Tenochtitlan, and there remain a few relevant places to visit. Beneath the city’s cathedral, for instance, archaeologists have found remnants of the Aztecs’ Great Temple and have placed bits of it behind glass for museumgoers to see. Outside the city, the impressive pyramids of such truly ancient sites as Teotihuacan still stand. But as hard as I had tried to experience a moment in which I felt ‘An Aztec person was here!’, nothing had ever worked. So I decided to try looking sidelong at the Aztecs, to go to the American Southwest, where their ancestors had come from. In Chaco Canyon, I thought, I might catch sight of one of their ghosts out of the corner of my eye.

It was people called Nahuas (NAH-was), speakers of the Nahuatl (NAH-wat) language and other closely related tongues, who travelled south in waves in the 10th through the 13th centuries. They forced their way through the rough, desert terrain, as dangerous to travellers then as it is now. It was mostly men who set out from home but, in their travels, they acquired women. They were adept warriors, and among the earliest to bring the bow and arrow with them down into Mexico. If your goal was to conquer a village, the stealth and speed offered by the bow and arrow gave a strong advantage over the more traditional spears. So the Nahuas often won their battles.

‘Perhaps we have done wrong. Perhaps because of it something may happen to our children’

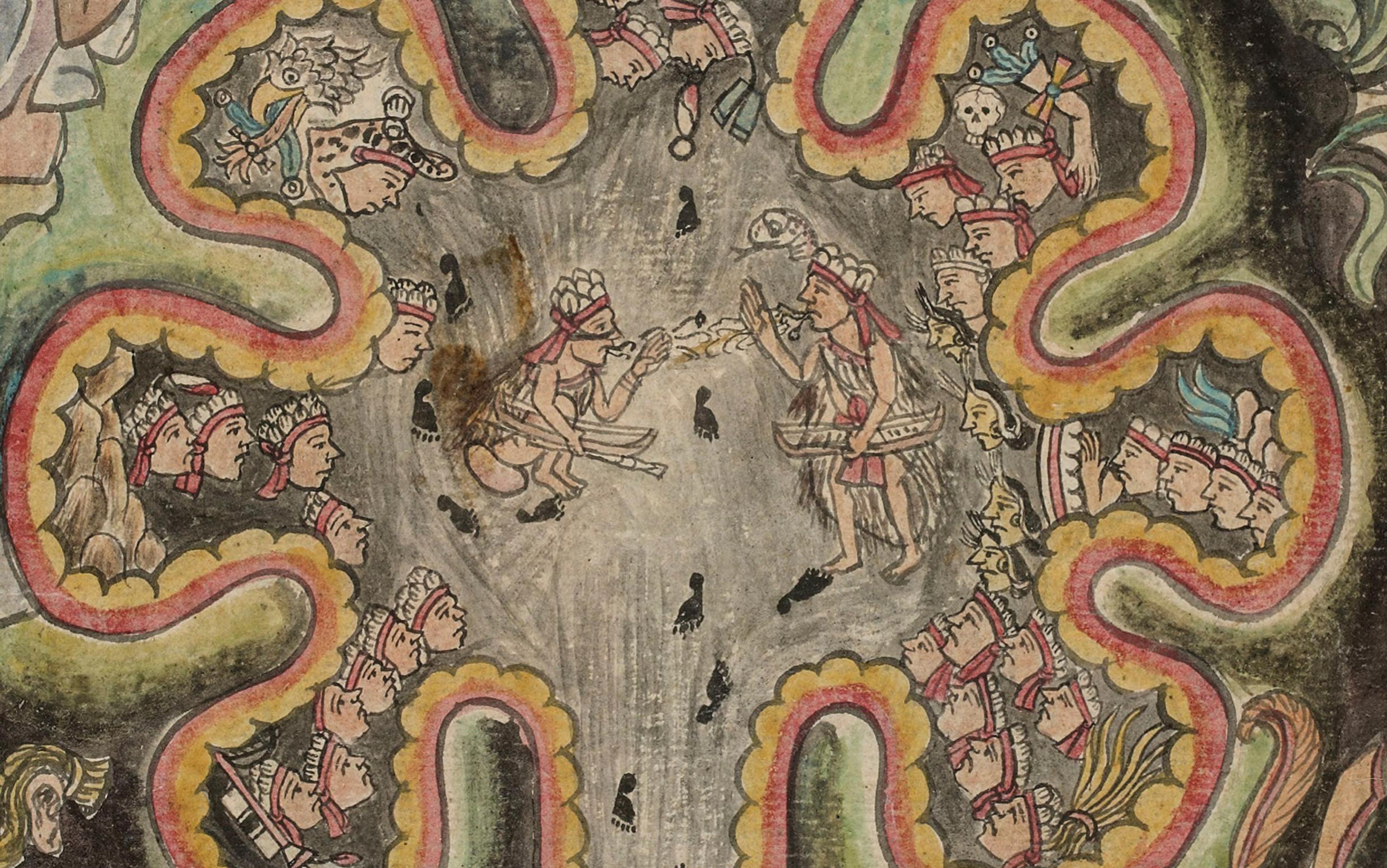

But they didn’t always want to fight; the texts they left us tell us that much. In the pictographic histories the Aztecs later painted, after they had arrived in the central valley of Mexico, their ancestors wended their way southward along paths marked by stylised footprints. (Later, after the Spaniards came, they sometimes illustrated the path of a group of migrants by marking hoof prints but, in these earlier times, they had never seen a horse.) Along the winding trails, they remembered, they sometimes stopped for a week, a year, or a century (which for them meant a bundle of 52 years), sometimes fighting, sometimes settling down. The histories give us hints about why battles erupted, even in the context of diplomacy and intermarriage. Life with other people was a minefield. They spent a great percentage of their time deciding to join up with another group, learning to live with them, or deciding to break apart.

Once a troublemaking chief of theirs had demanded a gift of four women from the Nonoualca (No-no-WAL-ca), another group with whom they had temporarily settled. The Nonoualca agreed, but when they later found that he had tied up the girls for sacrifice, their rage knew no bounds. They attacked their one-time friends and killed a great many. Fortunately, both sides came to their senses and realised they should blame the evil chief, not each other. But in a sense, it was too late. ‘When they got back [home],’ the history-tellers explained, ‘the Nonoualca gathered together and talked. … “What kind of people are we? Perhaps we have done wrong. Perhaps because of it something may happen to our children and grandchildren.”’ At length they decided they needed to break apart from those they had been allied with, to prevent bitterness and recriminations from visiting the next generation. They separated, though some Nonoualca spouses went with the Nahuas who had to move on. This was far from the end of the story. As they continued their wanderings, over and over they found themselves attempting to bond with other groups to become stronger and survive.

At every fork in the path, each group of Nahuas prayed to the god who had helped them most. Much like the ancient Greeks, they believed in all the gods they had ever heard of but understood that only one god was their special protector. The last group to embark on the great southward migration was called the Mexica (Me-SHEE-ka). It was they who were destined to become the strongest of all the Aztecs, the ones who would be in power when the Spaniards arrived. But the Mexica didn’t know their fate as yet. They simply trusted their god, Huitzilopochtli, Hummingbird-on-the-Left, as they moved south in line with real hummingbirds’ migration pattern.

By the 1200s, the Mexica had reached the central valley of Mexico. There they continued their practice of allying with others – often, in fact, working as mercenaries for other city states. Amid tough competition, they frequently came to grief and found themselves fleeing, or fighting for some territory they could call home. The people of the central valley – whom the Nahuas called the Toltecs, meaning ‘skilled craftsmen’ – had been practising agriculture for centuries and so the population was dense and land was at a premium. Eventually, the Mexica found an island at the centre of a huge lake. It was a reedy, swampy site that no one else seemed to want. When an eagle landed on a cactus, they decided that their God meant that they should stay. They built a little temple in the town they called Tenochtitlan, and desperately tried to manage the powerful groups who lived around them.

By the early 1400s, the situation had grown intolerable. In a bold move, a warrior named Itzcoatl, Obsidian Snake, a prior chief’s son by a commoner woman, someone who normally would never have become king, allied with other disempowered chiefs’ sons from two other nearby ethnic groups: together, in a moment of chaos caused by the death of a leading chief in the region, they took power – with each other’s help – in their three hometowns. Obsidian Snake soon came to dominate the Triple Alliance and he used the tight (forged-in-fire) connection with his allies to convince others to join them, and then to take territory from those who were recalcitrant; he had launched what has come to be called ‘the Aztec Empire’.

Obsidian Snake faced a difficulty common to many rulers: how to talk about history in such a way as to leave everybody (or at least most people) content with the status quo. He burned many of the pictographic histories, and commanded history-tellers to paint new ones. Propaganda, however, is of limited value in a face-to-face society in which almost everybody was there during a crisis and remembers what happened. The history-tellers needed to craft a careful story that fostered unity not division. They found a way to do this in keeping with the customs they had developed wandering south from the lands near Chaco Canyon. When the wandering travellers left the Nonoualca behind, many Nonoualca wives went with them. A story of the war that simply vilified the Nonoualca wasn’t going to work. So they told the story twice, once from the Nonoualca’s point of view, and then from the vantage point of those who had to depart.

The Aztec historians, creators of a genre called the xiuhpohualli (SHOO-po-WA-lee), developed a highly effective way of keeping satisfying memories alive. The pictographic texts that Itzcoatl burned were only a part of the Aztec way of keeping history. The glyphs served as mnemonic devices designed to elicit volumes of speech. The image of smoke billowing from a burning temple reminded the speaker to describe a certain group’s defeat. A winding sheet over a chief’s head sparked the story of his death. Certain memorable moments were always told exactly the same way. When a chief who ruled during the Aztecs’ early years in the central valley was captured in war, for instance, and he pleaded that his naked daughter be given a bit of clothing, the enemy always sneered and said the same few words: ‘No, she will stay as she is.’ Everyone waited eagerly for the memorable line they had been hearing all of their lives. But most of the time, the speakers enjoyed licence to improvise or simply change, as they liked. And in the details of the stories they told, a pattern emerges of a rotating vantage point.

It was a way of keeping history that literally depended on multiple speakers standing up at different moments

How can we know the details of exactly what they said? We have pictographic texts, but how can we possibly hear the words the history-keepers chose to speak aloud? Their narrations, counterintuitively in some ways, have been preserved because of the Spanish conquest. The Spaniards aimed to produce a local elite who would help them rule, and so they educated many of the boys and young men in the Roman alphabet. It was the priests who taught them, so they would be able to study the Bible. The Indigenous studied scripture with the friars and, inevitably, they took the sound transcription system home with them. There they asked elders to tell them the old histories, as they used to speak them aloud. And then the young scholars wrote down their elders’ stories, listening to the sounds of the words in Nahuatl, their own language, and transcribing them onto the paper in their best handwriting, in the alphabet taught them by the friars. ‘Zan iuh yaz,’ they wrote (‘She will stay as she is’) when the elders got to that part of the old story about the captive chief’s naked daughter. Dozens of these transcribed histories have survived in libraries, some in Mexico, some in Europe, and anyone who is willing to study Nahuatl (still a living language) can learn to read them.

For many years, however, scholars read them with scepticism. The histories weren’t like the books such as ‘the Florentine Codex’ that the Aztecs wrote working side by side with the friars, answering the Spaniards’ questions, drawing pictures of a specific plant or god. These were wide-ranging, confusing histories about mysterious, pre-conquest political dramas, often without any apparent narrative or context. They didn’t even proceed in chronological order. In fact, they frequently covered the same ground multiple times. One German scholar grew so frustrated that he simply rewrote the longest Aztec history, reorganising it as he thought it should have been done, putting all the material from one year together, rather than returning to the same year various times.

Recently, it has become clear to those who study these Aztec annals that repetition is a feature, not a quirk or bug. The reason is that whenever they came to a period of contention, or a place where things could have turned out quite differently, the history-teller turned into a sort of director, bringing a series of speakers to the fore in order to speak. So it was that the stories as a whole, when they were written down, seemed somewhat repetitive, and even contradictory. One group might remember a certain political marriage, a battle or a war one way; another might recall it differently. The advantage was that if each side had an opportunity to stand and speak its piece, the composite performance might stand unchallenged.

For the Aztecs, history didn’t require textbook-like consensus. In their understanding, truth wasn’t singular and could accommodate different perspectives. This pattern had almost certainly been part of their social practice for many generations, as they sat around campfires, talking and telling stories, trying to build common cause with the friends they’d made along their route. Now they turned it into an art form, a formalised way of keeping history that literally depended on multiple speakers standing up at different moments.

Yet this relativism didn’t mean that the Aztecs believed that there was no truth. Their historians never gave up on the idea that there is a truth that transcends differences in perspective. Their histories reminded listeners that, together, they had trekked a long way, over rough terrain and through painful events, to come to the present moment. They weren’t now about to give up everything with a shrug of the shoulders and an implicit conclusion that no one could ever know what happened or why.

In fact, the truth was that the past was still with them, the efforts of their multiple sets of ancestors still a part of who they were – and everybody present in the community needed to continue to give all they could in order to make the future come into being. They had survived their journey from the desert far to the north; they had survived bitter warfare in the central valley. By the mid-1500s, when they were transcribing the old performances, they had survived the arrival of the Europeans. This was no time to give up. Rather, it was a time to add another perspective, that of the Christians. Truth, they said again, was composite. History, they believed, was long – the trail of meandering footprints wound on for years – and it was constructed of such constituent truths. Writing in the colonial era, they wrote their own history interspersed with references to what they now knew had been happening in Europe at the same time and, when they arrived at the period after the conquest, they wrote about the efforts of both sets of people to manage their lives together. The new, they were convinced, didn’t necessarily have to obliterate the old.