Listen to this essay

35 minute listen

On the western slope of Mount Carmel, in Israel, lies the cave of Es-Skhul. About 140,000 years ago, during the Ice Age, nomadic hunter-gatherers made camp here. The sea to the west had receded, exposing a broad plain covered with groves of live oak, almond and olive, meadows filled with asphodel and anemone. Herds of fallow deer, rhinoceros and aurochs roamed the plains. People hunted animals with stone-tipped spears, and foraged wild mustard and olives. And when they died, they buried their dead by the mouth of the cave. The skeletons found here represent some of the earliest known members of our species, Homo sapiens. But these Homo sapiens were very different from us.

3D scan of Skhul V, recovered from Skhul cave. Courtesy the Smithsonian Institution

Their skulls retained anatomical features seen in primitive humans like Neanderthals – huge brow ridges, massive jaws, thick skulls. But, despite their primitive appearance, they weren’t our ancestors; they appear too late in time. They’re a side branch of our evolutionary tree, one that went extinct, leaving no descendants. Why did we survive, while they didn’t?

The answer may lie in their skulls. They lacked the peculiar anatomical traits that modern humans share – small brow ridges, bubble-shaped skulls, reduced jaws, thin cranial bones – which are typical of juveniles of other hominins and apes. Compared with other hominins, we’re literally baby-faced. Selection for juvenile traits – low aggression, openness to novelty and new people – likely made us more social, and produced our immature-looking skulls as a side-effect. Ironically, it may have been this sociability and low aggression that made modern humans so incredibly dangerous to these primitive Homo sapiens.

Skhul Cave was first excavated in 1929, and parts of 10 skeletons were eventually found. Soon after, the remains of at least 28 people, dating to 90,000 years ago, were discovered near Nazareth at nearby Qafzeh Cave. When they were first found, the Skhul and Qafzeh remains were among the oldest known Homo sapiens. Today, a century later, they still are, and their meaning is still debated.

Qafzeh skull. Courtesy Wikipedia

In a lot of ways, these people resemble us. They had high foreheads and domed heads, more like us than like Neanderthals, who had sloped foreheads and long braincases. Their brains were similar in size to ours. Their jawbones had strong chins; Neanderthals and other species had weak chins. But in other ways, the Skhul and Qafzeh fossils are strikingly primitive.

Their skulls have massive brow ridges, like Neanderthals and Homo erectus, and incredibly thick skull bones. Their jaws were broad and massive, with huge molars. We don’t know exactly what they would have looked like, but they probably didn’t look like anyone you’d see walking down the street today.

At Qafzeh, they punched holes in seashells, to string them on cords for necklaces

Artefacts found with the Skhul and Qafzeh fossils also reflect this mix of sophisticated and primitive. Their tools were part of a tool tradition known as the Mousterian. Mousterian tech was advanced compared with the primitive Acheulian tools like hand-axes used by early Neanderthals, but more primitive than the tools made by modern Homo sapiens. The Skhul and Qafzeh people had abandoned Acheulian hand-axes for smaller stone tools, striking flakes and blades of disc-shaped stone cores. They made big, triangular spearpoints called Mousterian points. To do this, they used a flintknapping style called the Levallois technique, where a stone core was prepared and a large blade was struck off in a single motion. Levallois points were attached to throwing spears to hunt big game – and probably other people. Curiously, Mousterian tools are also associated with the last Neanderthals. Did these Homo sapiens get their tools from Neanderthals – or did Neanderthals get their technology from them?

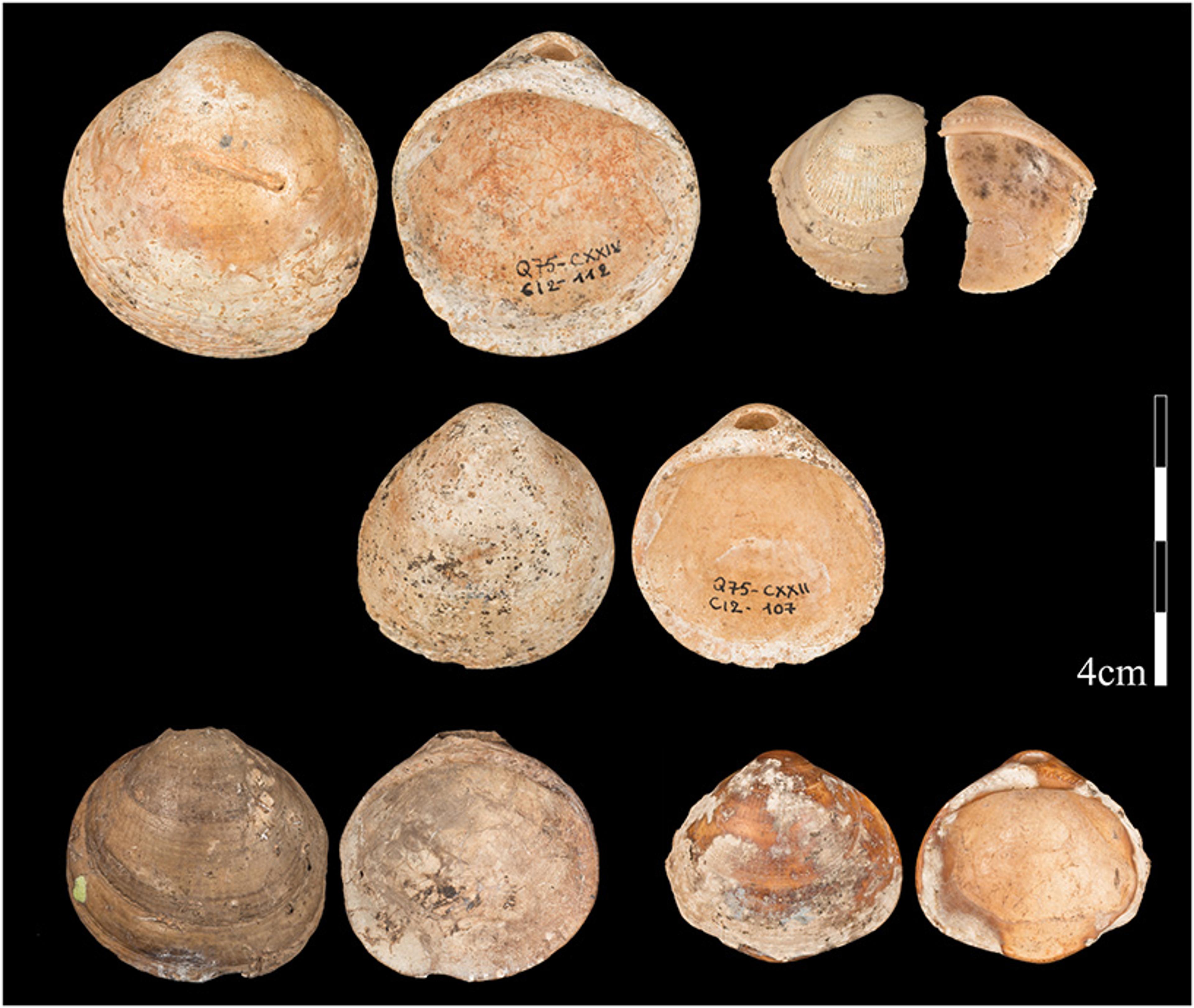

The artefacts and behaviours of the Skhul and Qafzeh people were in some ways surprisingly advanced, surprisingly human. At Qafzeh, they punched holes in seashells, to string them on cords for necklaces. Then, the sea would have been about 30 miles away. It’s possible their wanderings took them that far, but it’s also possible they traded for shells – a behaviour not known in Neanderthals. Ochre pigment, typically used for painting, makeup and decoration, was also found covering some skeletons.]

Remains of a teenage boy clutching antlers, discovered at Qafzeh cave. Courtesy the Israel Museum, Jerusalem/Wikipedia

And remarkably, several skeletons were found buried with grave goods, a practice unknown in Neanderthals. A man buried at Skhul had a boar’s jaw on his chest. A teenage boy at Qafzeh was buried curled up clutching the antlers of an elk. The meaning of this practice is unclear – maybe these artefacts were trophies, charms or offerings. Maybe they provided protection or help to the spirits of the dead. And then the burials themselves hint at the idea of an afterlife, and the mere fact that so many bodies are found in a small area suggests they attached some spiritual significance to these sites. Maybe loved ones brought the dead to the caves to join the ghosts of their ancestors.

For a century, archaeologists have tried to make sense of the Skhul and Qafzeh bones, but we’re far from a consensus. Even assigning the skeletons to a species has been contentious. For a time, the skeletons were given their own species; later, they were interpreted as transitional between Neanderthals and modern humans, or even as Neanderthal-human hybrids. The current thought is that they are part of Homo sapiens, more closely related to us than to Neanderthals. But if so, how do they relate to us?

The Skhul and Qafzeh remains are often called anatomically modern Homo sapiens, but the words ‘anatomically modern’ are doing a lot of work here. What archaeologists choose to emphasise is somewhat subjective – is the glass half-modern, or half-archaic? If you’re interested in the origins of modern humans, you might want to emphasise the modern aspects of their skeleton, but I find the primitive features more interesting. I like the term ‘archaic Homo sapiens’. This acknowledges both their link to modern people, and the gap between them and living humans. Alternatively, we might just call them the Other Sapiens.

Since the discovery of Skhul, archaic Homo sapiens have been discovered elsewhere in the Middle East and Africa. As often happens in science, more data has deepened the mystery. We’ve now found archaic sapiens in Florisbad, in South Africa. They’ve been found in East Africa, along the edge of Lake Eyasi in Tanzania, and in the Herto and Omo Kibish localities in Ethiopia. Archaic sapiens have been found in Jebel Irhoud and Dar Es Soltan in Morocco, and at Iwo Ileru Cave in Nigeria.

Archaic sapiens were the most widespread, abundant and successful humans of their time

Surprisingly, a few have even been found in Europe. An archaic sapiens skull was found at Apidima Cave in Greece, and teeth have been found in the cave of Grotte Mandrin, in France. They’re apparently part of an initial sapiens migration out of Africa, taking place tens of thousands of years before modern sapiens left that continent.

Archaic sapiens weren’t just common – they were the most widespread, abundant and successful humans of their time. Since archaic sapiens inhabited most of Africa where they had access to plenty of game and plants to forage, they would have outnumbered Neanderthals, who were restricted to the more hostile environments of Ice Age Europe and Asia. Modern sapiens, meanwhile, are thought to have existed in a small area of southern Africa, with a total population of no more than 30,000 people.

Archaic sapiens were also a long-lived people. The Moroccan remains, dating to 315,000 years ago, are currently the oldest known sapiens. A jaw from Misliya in Israel dates to 177,000 years ago, and the skull from Apidema in Greece dates to 200,000 years ago, making these the oldest sapiens outside of Africa. They were around for a long time. But they also survived until relatively recently. Until about 50,000 years ago, they were the dominant Homo sapiens. Before then, it’s difficult to find so much as a tooth or a jaw that doesn’t have archaic features like theirs.

All this raises questions. Where exactly do these primitive Homo sapiens fit into our evolution – were they our ancestors, or more likely, competing side-branches in the human evolutionary tree?

How modern – how human, for lack of a better word – were they in terms of their behaviour, and their minds?

Lastly, where did they go? Did they evolve into, or become absorbed into, modern populations – or simply go extinct?

And if they did go extinct, why – and why are modern humans still here?

It’s tempting to see archaic sapiens as our direct ancestors, because it would solve a big question – where we come from. In this scenario, the odd mix of primitive and modern traits seen in Skhul people and other archaic sapiens is because they’re transitional forms – ‘missing links’ between more primitive, Neanderthal-like hominins and fully modern humans. It’s a simple, obvious explanation, but as often happens, the simple, obvious explanation seems to be wrong. Archaic sapiens just appear too late in the fossil record to be ancestral to us.

Remains from the first modern humans have yet to be discovered

Exactly when modern Homo sapiens appear is still unclear. The hominin fossil record is frustratingly incomplete. The oldest fossils of fully modern humans appear in the form of a few teeth from Mumba Rock Shelter, on the edge of Lake Eyasi in Tanzania. They date to around 100,000 years ago, and lack archaic features – they’re indistinguishable from people living in Africa today.

Human genomes suggest that modern humans may have evolved much earlier – and that remains from the first modern humans have yet to be discovered. To estimate when our species emerged, scientists often use DNA divergence dating, a method that compares genetic differences between populations to calculate how long ago they split. These molecular clock techniques rely on the principle that mutations accumulate over time. The longer two populations have been separated, the more their DNA differs.

If we can estimate how fast DNA evolves, we can in theory calculate the time when two lineages diverged. It’s not an exact science – it’s almost a dark art – but molecular clocks offer one big advantage over fossils: they can peer back into time, even where the fossil record is missing. And in human evolution, most of the record is missing.

Applying a molecular clock model to modern humans suggests that our direct ancestors lived around 250,000-350,000 years ago. This population probably lived in southern Africa, somewhere between the Congo and the Okavango, where human genetic diversity is highest (and fossils are frustratingly rare).

These first modern humans probably looked a lot like us. Given that the descendants of these people – the San, Pygmies, Hadzabe, Bantu, and the diaspora giving rise to Eurasian and Amerindian peoples – have small brow ridges, delicate jaws and thin skulls, they probably did too. It’s likely they resembled modern African hunter-gatherers – short, wiry people, with copper or brown skin, and black, curly hair.

Archaics just keep on being archaic to the end. Then they disappear, and we appear

This implies that essentially modern humans had already evolved tens of thousands of years before primitive-looking people like Skhul and Qafzeh showed up in the Levant. If so, archaic sapiens can’t be our ancestors – the dates don’t work. Skhul and Qafzeh people date to around 80,000-120,000 years ago. The Herto remains date to around 160,000 years ago, and the Omo Kibish 1 skull to around 230,000 years ago. Remains from Grotte Mandrin in France date to about 54,000 years ago, and stone tools suggest that the last archaics in North Africa disappeared around 20,000 years ago. Finally, archaic sapiens in Iwo Ileru in Nigeria survived until around 12,000-16,000 years ago, just before the end of the last Ice Age. The archaics survived until very recently – long after modern humans had colonised Australia, after we spread out into Europe and Asia, and after we crossed the Bering Land Bridge into Alaska.

A few archaic sapiens appeared at about the same time that our ancestors would have lived. The Jebel Irhoud skull from Morocco dates to 330,000 years ago, and the Florisbad skull in South Africa dates to 250,000 years ago. But if they were truly ancestral, they should be either significantly older than modern sapiens, or far more modern in their anatomy. So the timing suggests that archaics aren’t our ancestors. Instead, they’re our cousins.

Another problem with the archaics-as-ancestors hypothesis is that the fossils don’t show an evolutionary trend towards modernity. If these archaic sapiens evolved into modern humans, we’d see the Skhul and Qafzeh people become increasingly modern, evolving smaller brow ridges and jaws in younger populations. But they don’t. Archaics just keep on being archaic to the end. Then they disappear, and we appear. This discontinuity suggests replacement, not evolution. Likewise, the transition in stone tools is abrupt, not gradual as we’d expect if they slowly evolved into modern humans.

Skhul people and other archaics weren’t on the evolutionary main line any more than Neanderthals were. They were competing lineages – like the Neanderthals, Denisovans and Homo erectus – that we beat out. These archaic side-branches must have split off the sapiens main line sometime after sapiens split from Neanderthals, around 750,000 years ago, but before modern humans evolved, around 300,000 years ago.

So how do these archaic lineages relate to modern humans? It’s possible that archaics represent a subspecies of Homo sapiens. More likely, given their wide geographic spread and anatomical variation, they represented multiple subspecies. Within modern humans, we see distinct groups in different regions – the San in southern Africa have been evolving more or less in isolation for 300,000 years, and the Pygmies in Central Africa split off from the remaining humans around 200,000 years ago, and so on. In the same way, early Homo sapiens probably saw lineages split off and migrate into different parts of Africa, the Middle East and Europe over hundreds of thousands of years. Some lineages were probably closer to modern humans than others. The Jebel Irhoud sapiens, from Morocco, look even more primitive than the others – theirs is an elongate braincase, almost like a Neanderthal. This is an archaic archaic human. The Skhul and Qafzeh hominins are among the most modern in their anatomy, and may have been closer to us.

But what does it even mean to call them ‘side-branches’? What we call the ‘main line’ and what’s a ‘side-branch’ is clear only looking back. We can call ourselves the main line because we’re here, and they’re not. Winners write the history books, and the anthropology textbooks. But, at the time, we weren’t obviously the main line, and they weren’t obviously side-branches. Modern Homo sapiens was one, not particularly successful, side-branch, with a total population of perhaps 30,000 individuals among many competing sapiens lineages. If an alien exobiologist had come to Earth to study Homo sapiens, could they have predicted our bubble-headed subspecies would replace all the others?

Just how human were archaic sapiens, anyway? We know their brains were big, within the range of variation seen in modern humans, although a bit below average. They were also anatomically similar to us, so it’s reasonable to think they resembled us in terms of behaviour. They likely had complex languages, complex tribal structures, and other features shared by all human cultures. They may have believed in gods, ghosts and magic. These conclusions are speculative, but not entirely without evidence. That archaic sapiens buried the dead implies some sort of supernatural belief. The Hadzabe hunter-gatherers of Tanzania place their dead in rock-shelters to join their ancestor-spirits; it’s possible the people who lived at Skhul and Qafzeh buried their dead in caves for the same reason, and they too believed in ghosts and ancestors. Moreover, the fact that certain features of modern humans are highly complex – language, dance, song, music, spirituality – implies that these features had a long history before we evolved. Language in particular is an incredibly complex adaptation – it’s extremely unlikely it emerged in the few hundred thousand years of evolution separating us from other humans. Instead, it probably emerged gradually, just as our modern skeletal structure did. So it’s reasonable to guess they had some form of language.

Archaic sapiens never invented the sort of advanced technology modern sapiens did

We also see the Skhul and Qafzeh people making extensive use of shell beads and red ochre pigments, like modern humans; they may have had a sense of beauty and vanity, like we do. A striking feature of the archaics is that they sourced materials over long distances, something we don’t see in Neanderthals. Qafzeh Cave would have lain around 30 miles from the sea, yet somehow these people got marine snails to make shell beads. There are two ways to acquire resources over such long distances. One is to walk there through friendly territory. This implies a relatively large area controlled by a single, large tribe, as we see in the Sand and Hadzabe hunter-gatherers, where a tribe of 1,000 can control an area more than 4,000 square km (1,500 sq miles). The other is to trade with neighbouring tribes. Either scenario implies large, geographically extensive social networks.

Shells from Qafzeh cave. Photo courtesy Oz Rittner/CC by 4.0

But what’s also striking are the advanced behaviours we don’t see. Archaic sapiens never invented the sort of advanced technology modern sapiens did. They had no bows, no spear throwers. They didn’t carve ivory Venus figurines, or make cave paintings of horses. Neither do they show rapid technological evolution. For 100,000 years, the Skhul and Qafzeh people seem to have used the same tools as the Neanderthals. Technological innovation takes off only once modern humans become widespread in Eurasia, around 50,000 years ago.

Another remarkable feature of the archaics is that they struggled to hold off the Neanderthals. The archaics gained a foothold in the Middle East, eventually spreading as far as western Europe. Yet this incursion into Neanderthal territory ultimately failed. They were gone by 150,000 years ago in Greece, 70,000 years ago in Israel, and 55,000 years ago in France, replaced by Neanderthals. That’s very different from the pattern we see in modern sapiens.

After initially spreading out of Africa into the Arabian Peninsula around 100,000 years ago, modern Homo sapiens would stage a rapid breakout into the Middle East, Europe and Asia around 50,000 years ago, wiping out all Neanderthals by 35,000 years ago. In no case were Neanderthals ever able to push back against modern sapiens and retake lost ground. Modern humans had an edge over the Neanderthals. We don’t know what that edge was, but the archaics apparently lacked it.

And whatever it was that gave us an evolutionary edge over the Neanderthals, it must have given us an advantage over archaic Homo sapiens.

So why did the archaics disappear? Likely for the same reason that Neanderthals, Denisovans, Homo erectus, Homo rhodesiensis, and all other primitive human lineages vanished. Modern humans spread and took their place. We either killed them outright, or drove them away and took their land. Left with less and less territory to hunt and gather to feed themselves, they became fewer and fewer in numbers. In time, they disappeared entirely.

We see this pattern again and again in human history – when one human population replaces another, it’s almost always through violence, or threat of violence. When American settlers and military took Native lands, they did so by force. Before that, Native American tribes fought and took land from other Indigenous peoples. The British forcibly seized lands from Aboriginal peoples in Australia and Māori in New Zealand. In South Africa, the Bantu farmers and Khoikhoi herders took the lands of the San people.

This happened gradually. Studies of human genetic diversity suggest that modern sapiens originally existed at low numbers – perhaps 25,000 to 30,000 people. Assuming population densities like those of African hunter-gatherers, the entire population would have comfortably fit into an area the size of England or Iowa. Meanwhile the rest of Africa – Ethiopia, Tanzania, South Africa, Kenya, North Africa, along with parts of the Middle East and Europe – was home to archaic sapiens. But, slowly, modern humans spread out.

As we expanded throughout sub-Saharan Africa, we increased our numbers. We replaced archaic Homo sapiens in South Africa and East Africa. Then we expanded out of Africa. We first took a coastal route into Southeast Asia where we wiped out Homo erectus. Then modern humans saw a rapid expansion around 50,000 years ago – perhaps driven by the acquisition of the bow and arrow – with modern humans rapidly replacing Neanderthals in Europe and the Middle East, and the Denisovans in East Asia. Finally, we migrated into North Africa, displacing the archaic sapiens there around 24,000 years ago. The last known archaic sapiens disappeared in West Africa around 13,000 years ago. The archaics survived remarkably late – long after Neanderthals, after Denisovans. Even after modern humans reached Australia, Europe and the New World.

The extinction of archaic humans was therefore part of a broader wave of extinction that saw modern humans replace all other human lineages. When we first appeared, there were perhaps 10 different hominin species, of which we are the only one to survive. But even our own species was once far more diverse; the surviving Homo sapiens is just one of many different branches of our tree.

The extinction of archaic sapiens may not have been total. It’s possible that modern humans intermarried with these people, as we did with Neanderthals, Denisovans and perhaps Homo rhodesiensis – humans seem to have a thing for cross-species mating. If so, some archaic DNA might survive in modern human populations. At least some skulls do show hints of hybridisation. A modern Homo sapiens skeleton from Nazlet Khater in Egypt dates to 33,000 years ago, making it among the oldest modern humans in North Africa. While the remains are mostly modern, the jaws retain some primitive features; it’s possible the Nazlet Khater skeleton is a hybrid. So archaic genes may have entered modern populations in North Africa, maybe elsewhere too. Such interbreeding might be hard to recognise – interbreeding of sapiens with sapiens would be far less obvious than interbreeding with Neanderthals, either in terms of skeletal anatomy, or in terms of DNA.

Modern Homo sapiens always took ground against other hominins, and we never gave it up

Archaic DNA may also have entered our genes in a more roundabout way. Modern non-African people inherited about 1-2 per cent of their DNA directly from Neanderthals. But, curiously, studies of Neanderthal genomes suggest that around 6 per cent of their DNA was inherited from Homo sapiens in a hybridisation event that took place about 250,000 years ago. That’s long before modern humans left Africa, and about the time archaic sapiens moved into the Levant, suggesting archaic Homo sapiens was the source. If so, then, statistically speaking, it’s likely that some of the genes modern humans acquired from Neanderthals might originally come from archaic sapiens, in a sort of genetic back-and-forth.

A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests about 0.1 per cent of the DNA in non-African populations could come from archaic sapiens this way. That doesn’t sound like much, but it adds up to around 3 million base pairs out of the 3.2 billion base pairs making up the human genome. And any genes that persisted first in Neanderthals, and later in ourselves, were likely kept due to natural selection – there’s a good chance they’re doing something useful to our bodies, our physiology – or our brains.

So was our survival, and their extinction, a foregone conclusion, or just dumb luck?

The striking pattern we see in the archaeological record is that modern Homo sapiens always took ground against other hominins, and we never gave it up. Everywhere modern humans went, we displaced archaic sapiens, never the reverse – as with Neanderthals and Denisovans. They held us off for a time, sometimes for millennia, but other humans could never push back and retake the land they lost. In civilised history, the rise and fall of civilisations often came down to a few big battles, so luck must play a large role in, say, the rise of Greek civilisation versus Persian.

But prehistoric wars were settled by small raids and ambushes, wars of attrition waged over millennia – the success of modern humans must be the result of countless thousands of conflicts. We won consistently, more often than we lost. Our success wasn’t a fluke; we weren’t just lucky, we were better than the other humans. Modern humans had an edge – so what was it?

One possibility is that we were better with tools and technology. Modern humans invented weapons like bows, spear-throwers and stone-headed axes; archaic sapiens and Neanderthals neither invented them, nor did they even adopt these technologies from us. Technological superiority wasn’t just about weapons, either. Modern Homo sapiens migrated into the high arctic of Siberia around 40,000 years ago, during the middle of the Ice Age – something Neanderthals never did. That’s strong evidence that we mastered innovations like cold-weather clothing, shoes, and the needles and thread needed to sew them. Modern humans colonised Australia by boat around 65,000 years ago; no other lineage crossed long distances over water.

Another possibility is that we were better with language. Language wasn’t unique to modern humans; Neanderthals probably had a form of speech. The hyoid bone that supports the soft tissues of the throat is highly modern in Neanderthals; they also had modern ear anatomy, suggesting they could hear the sounds of language. But it’s possible we were more refined linguistically, better able to communicate with one another to socialise, and also to wage wars, compared with other humans.

We might also have had other more subtle advantages. One of the most extraordinary features of modern Homo sapiens is how we form large social groups. African hunter-gatherers typically live in bands of several dozen people, which ally to form tribes of many hundreds or even 1,000 people. Meanwhile, studies of Neanderthal DNA show low genetic diversity, suggesting more inbreeding – they lived in smaller, more isolated social groups. Our big social groups must have given us more brains to solve problems and to devise techniques for making tools. But maybe more important is the fact that large tribes are better able to defend land – or take it. If archaic Homo sapiens resembled Neanderthals in having small social groups, this must have put them at a disadvantage against modern humans.

It’s obviously hard to reconstruct social structures for people who lived tens of thousands of years ago. Still, could the anatomical differences between us and the archaics tell us something – could a clue to our superiority lie in modern humans’ weird skull shapes, where juvenile features are retained into adulthood?

A similar pattern is seen in domestic dogs – dog skulls are shaped like those of wolf puppies, and they have thinner skull bones too. The process of domesticating dogs for lower aggression produced something that looks like a young wolf. This may be a side-effect of selecting dogs for characters found in wolf puppies – less aggression, more playfulness, more friendliness.

So it’s possible that a sort of process of domestication gave modern Homo sapiens our weird, immature skulls, including big, domed heads, loss of brow ridges, small jaws, and thin skull bones. If the bones look immature, maybe the brain inside was too. Perhaps youthful creativity, imagination, faculty for languages, playfulness, why’s-the-sky-blue curiosity, willingness to make new friends were all retained late in life in us, compared with other humans – with selection for child-like behaviours creating our child-like faces.

The expansion of modern humans was a long, gruelling war of attrition, not a blitzkrieg

Paradoxically, low aggression may have been a massive advantage in intertribal warfare. Low aggression could have helped us to form big social groups – tribes of hundreds and thousands. And modern humans don’t just form huge groups, we’re unique among animals in being able to form peace treaties between different groups, and alliances between groups to defend or attack territory. What made modern Homo sapiens so uniquely dangerous might not have been a tendency towards violence and aggression, but friendliness, and the ability to forge alliances. The ability to create groups and social networks, and hold off fighting – at least, until we’re in a position to win – could have given us a decisive edge.

I alone am survived to tell thee. Today, all human diversity derives from a small population that lived a few hundred thousand years ago. The picture was very different when we first evolved. Then, there were 10 or more different human species. All of them have since disappeared.

Within Homo sapiens, we see this pattern repeated, with lineages others than our own stripped away, a diversity of peoples whittled down until only one remains. We were just one of many different lineages, but now we’re alone. All that remains of the others are stone tools, a few skeletons, perhaps a few of their genes mixed with ours.

We don’t know how this replacement played out. In some cases, the large size of modern human social groups probably allowed our ancestors to move in and seize territory without a fight, forcing archaic humans onto more marginal land. But in many cases, the conflict between modern humans and archaic sapiens was likely violent. The remarkably slow spread of modern humans – it took perhaps 300,000 years for us to completely displace archaic sapiens in Africa – implies that archaic humans resisted fiercely and effectively. It took hundreds of thousands of years of intertribal warfare for modern humans to spread from our homeland in southern Africa to the far edges of the continent. Even the final, rapid push from Egypt to the northwest tip of Africa took more than 10,000 years – just half a mile per year. The expansion of modern humans was a long, gruelling war of attrition, not a blitzkrieg. This also tells us something about just how human they were – the edge we had was decisive, but not overwhelming – they must have been very like us to fight us off for so long.

The evolution of the human species, much like art, would have been both an additive and a subtractive process. Shakespeare put words on the page, then deleted lines and whole scenes. Evolution is the same. It adds new genes to a population through mutation. It subtracts genes by eliminating individuals, populations, entire species. When Michelangelo sculpted the statue of David, he chiselled away every piece of stone that didn’t look like the ideal human form. In the same way, evolution worked on the raw material of Homo sapiens, carving away everything that wasn’t a modern human. To be more precise, we ourselves did the carving, slowly stripping away other species and other lineages, until modern humans remained.

This process didn’t begin with us. Over millions of years, increasingly advanced hominin species appeared, with bigger brains and more advanced tools and language. They tended to displace the more primitive species. The acquisition of spear-throwing and hunting by Homo erectus probably saw the primitive Australopithecus species killed off – even hunted and eaten – by their advanced rivals. And in the Levant, we see a series of species move through, as new and more advanced hominins evolved in Africa and then migrated out – the ancestors of Homo erectus, Homo antecessor, Neanderthals, archaic humans and, finally, modern humans, each wave replacing the one that came before.

This process did, however, end with us. After thousands and millions of years, one lineage emerged to replace all the others. This probably explains something about our history, and our tendency towards war and conflict. We may live in civilisation today, but the genes within us are those that made us the sole survivors of hundreds of thousands of years of intertribal conflicts and bloody, genocidal wars. We replaced all the other humans because we were more dangerous than all the others.