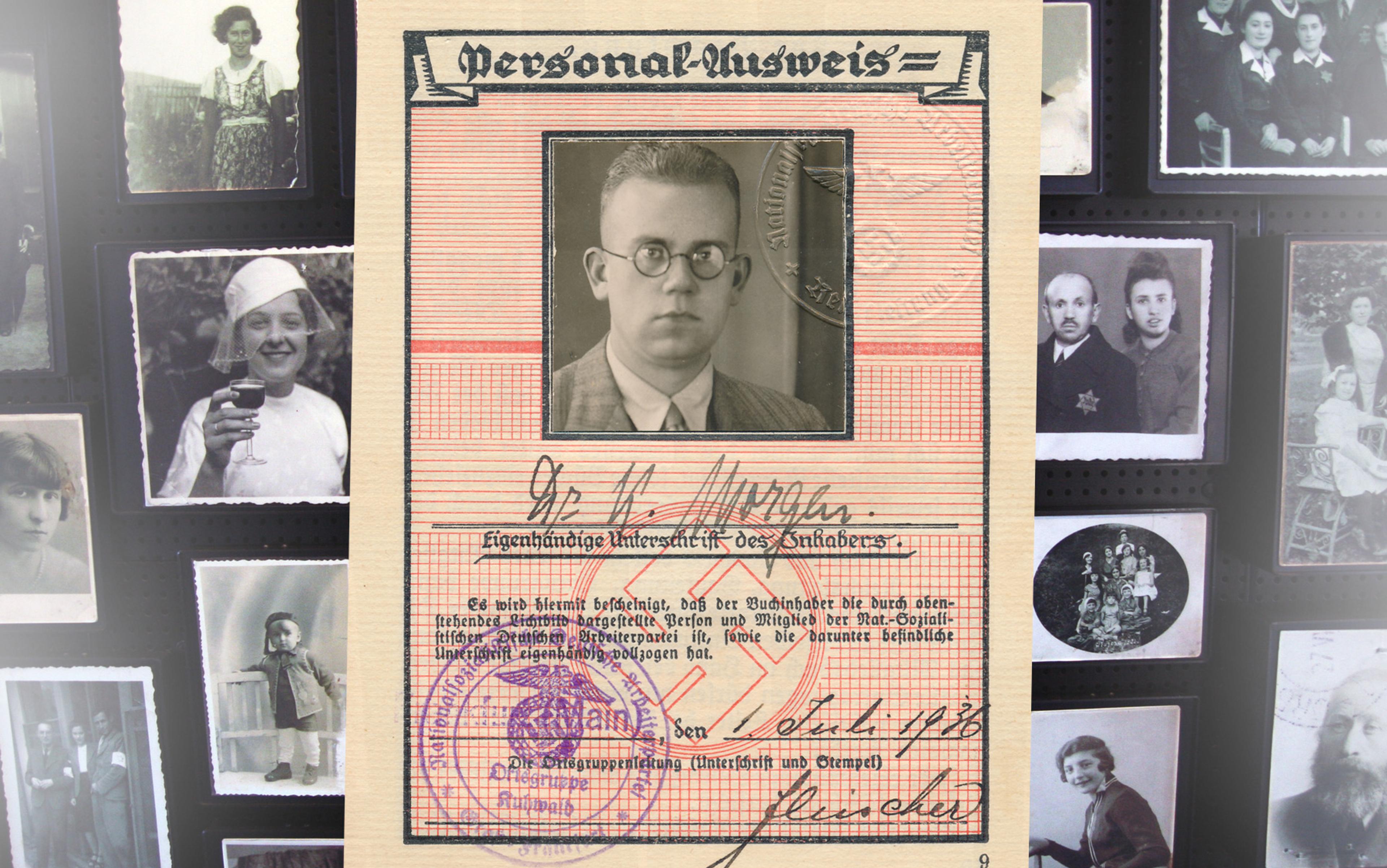

Georg Konrad Morgen was the first man to prosecute commandants of the Nazi concentration camps, but he wasn’t an officer of war-crimes tribunals. He was himself a German SS officer, and he prosecuted his fellow SS officers in SS courts during the Second World War. Morgen charged them not with crimes against humanity but with ordinary crimes of corruption and murder. While investigating those crimes, he came upon the machinery of mass murder at Auschwitz-Birkenau and, recoiling in horror, he asked himself what he could do about it.

But, as he explained after the war, that machinery was set in motion by Hitler, whose will was law in the Führer-State: mass murder had become ‘technically legal’. All he could do, he said, was to forge ahead with prosecuting the perpetrators for ‘illegal’ killings and lesser crimes, in the hope of somehow throwing sand in the works. He even sought an arrest warrant for Adolf Eichmann – but only for embezzling a pouch of diamonds.

Morgen was a judge in the SS Judiciary, a system of courts that tried cases against members of the Nazi Waffen-SS, much as military courts try cases against members of the military. In 1941 and the first half of 1942, he investigated financial corruption by members of the SS in occupied Poland. In July 1943, Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer of the SS, chose Morgen to investigate SS corruption in the concentration camps. The trail of those investigations led him to the threshold of the gas chambers.

Morgen’s first assignment in the SS judiciary in 1941 was in Kraków, the seat of German administration in the portion of occupied Poland not incorporated into the Reich. Shortly after arriving there, Morgen began investigating members of Himmler’s circle, displaying remarkable nerve and perhaps also naivety – qualities that would appear repeatedly throughout his career.

His foremost suspect in Kraków was Hermann Fegelein, who led the mounted regiment of the SS. Fegelein was a favourite of Himmler’s, and later his liaison to Hitler. In 1944, he would marry Gretl Braun, Eva Braun’s sister. A year before coming to Morgen’s attention, Fegelein had been accused of trucking stolen property from Poland to his family’s riding school in Munich. When a search of the school uncovered goods of questionable provenance, Fegelein appealed to Himmler, claiming the property was of legitimate origin and the accusations born of malice. Himmler wrote to the Reich Security Head Office supporting Fegelein’s claims and the investigation was closed.

Morgen suspected Fegelein of looting a Jewish fur company that had been confiscated – ‘aryanised’ in Nazi parlance. Another Nazi cavalryman, Albert Fassbender, had been placed in charge of the company as its liquidator. Both Fegelein and Fassbender took employees of the company as mistresses, who helped them to embezzle its assets. Fassbender’s mistress, Jaroslawa Mirowska, was ideally placed for this exploit, since she had previously been the lover of the firm’s Jewish owner, who had fled the German invasion and left her in charge.

Again, Himmler came to Fegelein’s defence. He wrote that he knew and approved of the suspects’ plan for the firm. The ostensible plan was to turn the company, with its international connections, into a contact point for German agents. Himmler said it was thanks to Fegelein, Fassbender and Mirowska that the value of the firm had been salvaged – meaning, presumably, converted into an intelligence asset.

‘she is intelligent and unscrupulous, expert in languages, known internationally, a leader in society and fashion – an excellent tool for espionage’

With her sweet smile and open face, Mirowska had charmed Himmler. According to Morgen, she was treated as ‘the first lady of the SS’, but Morgen’s interest in her was purely prosecutorial. In September 1941, he summarised the Fegelein case for a new investigator, unmasking Mirowska as a fraud. She was not, as she claimed, the daughter of a Russian father and German mother: she was pure Polish. Nor could Morgen find any evidence to support her claim to be working with the German security service. Taking over the firm to incorporate its international network into the intelligence service was a good idea, Morgen allowed, but, he added: ‘This idea has so much going for it that I can’t imagine the Polish regime had not already made use of the possibility.’

Morgen suspected that Mirowska was a spy for the Polish underground, a suspicion he supported with several pages of circumstantial evidence. His conclusion: ‘[A] woman as beautiful and charming as she is intelligent and unscrupulous, expert in languages, known internationally, a leader in society and fashion – she would be an excellent tool for espionage.’

Nine days later, the new lead investigator sent Himmler a memo marked ‘Urgent’, ‘Secret’, and ‘To the Reichsführer personally’. He wrote that Mirowska, the purported half-Russian, had misrepresented her past and appeared to have ‘dangerous contacts’. Morgen’s suspicions were borne out: ‘One year later,’ he recalled after the war, ‘the whole Polish underground was rolled up and Frau Mirowskaja, the first lady of the SS, was their head agent.’ Mirowska had sold Himmler on the idea of using the firm to gather intelligence, but she was working as a double agent for the Poles.

In the end, Himmler let her go. ‘A call came from the Reichsführer,’ Morgen continued. ‘The message was: Yes, Mirowskaja is a spy.’ When asked where she should be tried, however, ‘Himmler said, “No, no – that isn’t going to happen,” and he snatched her from the jaws of the Gestapo.’ Himmler’s intervention on behalf of a known spy indicates the risk that Morgen had taken in accusing her. As he would later write to his fiancée, it was his ‘fate’ to pursue his investigations into ‘the highest regions’ of power. For his temerity, Morgen was removed from the judiciary and sent as a soldier to the eastern front, where the Soviets had just begun their counterattack at Stalingrad.

However, in early 1943, Himmler himself recalled Morgen to resume his investigations of SS corruption, this time in the concentration camps. Himmler’s growing concern about corruption can be seen in his infamous Posen speech to SS officers on 4 October 1943. Speaking of the victims of the gas chambers, Himmler reminded the officers that their property must ‘be handed over to the Reich without reserve’:

Whoever takes so much as a mark of it, is a dead man. A number of SS men – there are not very many of them – have fallen short, and they will die, without mercy. We had the moral right, we had the duty to our people, to destroy this people which wanted to destroy us. But we have not the right to enrich ourselves with so much as a fur, a watch, a mark, or a cigarette or anything else.

Morgen’s work on corruption in Kraków in 1941-42 had been thwarted by Himmler, but it now recommended him for the job of investigating similar crimes in the concentration camps. So he was reinstated in the SS judiciary.

Morgen then spent the latter half of 1943 on cases of corruption at Buchenwald, Dachau and other camps, including Kraków-Płaszów, the camp made famous by the film Schindler’s List (1993). In one scene from the movie, workers are unloading provisions ordered for 10,000 prisoners – non-existent prisoners invented by the commandant, Amon Göth, so that he could requisition extra provisions to sell on the black market. The narrator remarks that Göth is being audited by the SS. In fact, the investigators were working for Morgen.

Morgen did not confine his investigations to corruption. He found that prisoners in Buchenwald were disappearing – especially those who had witnessed corruption – and he inferred that they had been murdered. Exceeding his brief, he drew up charges of murder against the commandant of Buchenwald, Karl Otto Koch.

But then Morgen discovered killings on a vastly greater scale. He narrated his discovery 20 years later, in 1964, to a courtroom in Frankfurt, where, from 1963 to 1965, perpetrators from Auschwitz stood trial for war crimes. Morgen was a key witness at the trial, having seen all there was to see at Auschwitz and its sister camp of Birkenau – seen it, moreover, with the eye of prosecutor:

My investigations in the concentration camp of Auschwitz were triggered by a small package in the military mail. It was a somewhat small packet, long rather than short, an ordinary box, which had probably come to the attention of the postal service because of its enormous weight, and the customs investigators had confiscated it because of its contents. It contained three lumps of gold. [I]t was high-carat dental gold that had been crudely smelted together. It was a very large lump, perhaps the size of two fists; the second was considerably smaller, the third less significant. But in any case, it was a matter of kilos … I knew that the dental wards of the concentration camps were tasked with collecting the gold that accumulated from the burning of bodies and send it to the Reichsbank. And a gold filling is only a few grammes: 1,000 grammes, or several thousand grammes, thus represented the death of several thousand people. But not everyone had gold fillings in that impoverished time, only a fraction. And depending on whether one estimated that one 20th or 50th or 100th had gold in their mouths, one had to multiply the number, and so this confiscated shipment represented as it were 20- or 50- or a 100,000 bodies. [Pause] A shocking thought.

A natural cause of death wouldn’t have done it: those people must have been murdered.

I could have dealt with the case of this confiscated gold shipment very easily. The pieces of evidence were conclusive. I could have had the perpetrator arrested and accused, and the matter would have been taken care of. But given the reflections that I have briefly delineated for you, I absolutely had to have a look for myself. So I went as quickly as I could to Auschwitz, in order to carry out inquiries on the spot.

I reported to the commandant, Standartenführer Höss, a somewhat stocky, taciturn, monosyllabic man with a stony face. I had already notified him by telegraph of my arrival and let him know that I had inquiries to make. He said something to the effect that they had been handed an enormously hard assignment, and not everyone had the character for it. He then asked curtly how I wanted to begin. I told him that I must first tour the whole camp … He looked quickly at the duty roster, made a phone call, and a Hauptsturmführer came. And he directed this man to drive me around the compound and show me everything I wanted to see. I started with the beginning of the end, namely, the ramp in Birkenau.

The ramp looked like any other ramp at a freight terminal. There was nothing special to discover there, no special precautions being taken. So I asked my guide how it went. He explained to me that the camp was notified by the station of a transport, usually of Jews, shortly before arrival, before it was due in Auschwitz. Then a guard unit was called out and they cordoned off the tracks and the ramp. Then the doors of the cars were opened, and the arrivees had to disembark and put down their luggage.

The ones who were fit for work marched on foot into the camp of Auschwitz, were duly recorded as prisoners, outfitted, divided into groups. The others had to take a seat in a lorry and went, without their names being taken, straight to Birkenau and into the gas chambers. My guide told me, with black humour, that if there was no time, or no doctor was present, or there were too many arrivees, they occasionally shortened the procedure by telling the arrivees in polite terms that the camp was several kilometres away, and whoever felt too sick or too weak or would find it uncomfortable to walk could make use of the transport facilities that the camp had provided. Then there was a stampede for the vehicles. And only those who didn’t join in could march into the camp, while the others had unwittingly opted for death. [Pause]

From the ramp we followed the path of the death cargoes to the camp Birkenau, which lay a few kilometres away. Outwardly there was again nothing remarkable to be seen: a large mesh-wire fence, a bit warped, with a guard. Behind it lay the so-called camp ‘Canada’, where the effects of the victims were searched, put in order, recycled. You could see a pile of burst-open suitcases from the previous transports, items of lingerie, briefcases, but also complete dentist’s equipment, cobbler’s equipment, medicine bags. Obviously the so-called evacuees really had the impression, as they had been told, that they were being resettled in the East and would find a new life there, and had therefore brought all the necessities with them. [Pause]

And in the back were the crematoria. They were one-story, gabled buildings that could just as well have been small workshops or work-sheds … In the back of the courtyard was a big gate that led into the so-called changing rooms, like the changing room of a gym. There were simple wooden benches with clothes racks, and each spot was clearly numbered and had a locker tag. And the victims were instructed to take note of their locker and hold on to their locker tag – all so as not to let them have the slightest suspicion until literally the last second, and to lead the condemned into the trap without a clue.

On the wall was a big arrow pointing to a corridor, and on it the terse words ‘To the showers’ repeated in six or seven languages. They were told: you folks undress and you’ll be showered and disinfected. And on this corridor there were various chambers with no furnishings – cold, bare, a cement floor. What was noticeable and at first inexplicable was that there was a grated duct in the middle, reaching to the ceiling. At first I could think of no explanation for it, until I was told that gas – Zyklon B in crystalline form – was poured into this death chamber through an opening in the ceiling. Until that moment the prisoner was clueless, and then of course it was too late.

Understandably, I couldn’t sleep a wink that night. I had already seen some things in concentration camps, but never anything like that. And I considered what could be done about it.

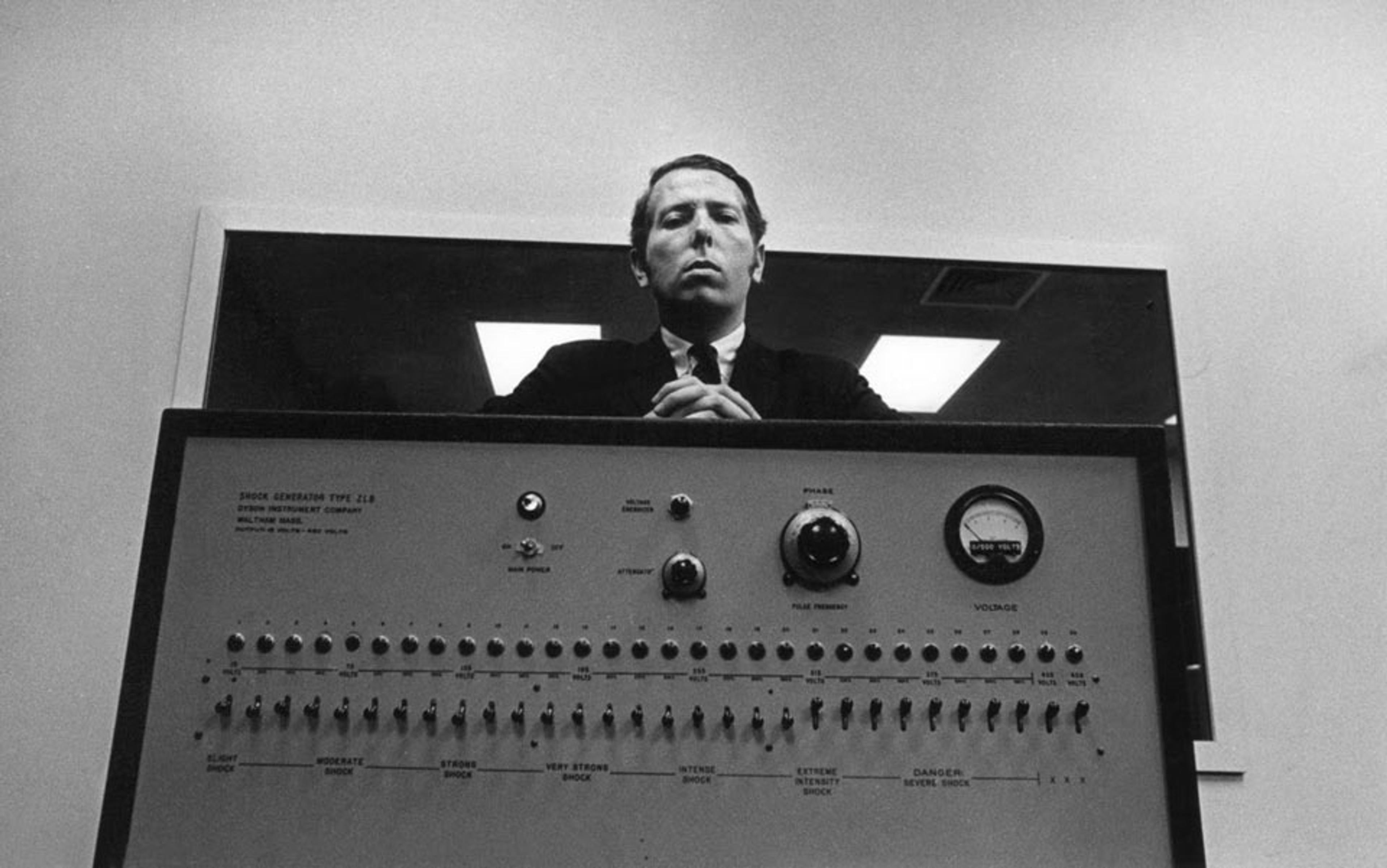

Morgen reported what he had found to several of his superiors, including the chief of the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller: ‘Obergruppenfuehrer Müller was surprised to hear about the illegal executions in the concentration camps, namely about the acts committed in the concentration camps against the law, and he was also surprised at the large extent of crime, but he was not at all surprised that there was an extermination of the Jews, that there were [sic] inhuman treatment which had been ordered, and, he said to me, ironically, “Why don’t you arrest me?”’

Morgen had reached the limits of his judicial powers. So he did the only thing he could think of, by bringing some of the perpetrators to trial on other charges. He found that Maximilian Grabner, chief of the Gestapo at Auschwitz, routinely killed prisoners in the camp jail when it became too crowded. Of course, Morgen realised that these murders paled in comparison with the horrendous crime he had uncovered, but that crime had been ordered by Hilter, and so prosecuting ‘illegal’ killings such as Grabner’s was all he could do to interfere.

The trials of Koch and Grabner took place in the autumn of 1944. Hostile superiors sent several SS officers to observe. They gathered after hours with members of the court and denounced Morgen as a self-promoter, a liar, and an enemy of the SS. Morgen felt himself to be on trial. He was rumored to be ‘a dead man’; a warrant of arrest was said to be waiting for him at the trial’s end. In a dramatic letter to his fiancée, he wrote: ‘Defenseless, I stood alone in the storm as the object of the tribunal. […] It is a sad and thankless business to be the state’s prosecutor of state institutions.’

Buchenwald commandant Koch was convicted, but only on a charge of corruption, though he was indeed executed in 1945, shortly before the end of the war. The trial of Auschwitz Gestapo chief Grabner was recessed until the spring, never to resume. Grabner’s punishment had to wait until 1948, when he was executed by a war-crimes tribunal in Poland.

‘the leadership of the state was destroying its own moral foundations with these monstrous crimes’

After the war, Morgen was taken into custody and extensively interrogated by the US Counterintelligence Corps (CIC). He testified at numerous war-crimes trials – first at the Nuremberg trial of major war criminals held by the Allied forces in 1945-46, then at several lesser trials in the immediate post-war period and, finally, after establishing himself as a lawyer in Frankfurt, at the later wave of trials that began in the 1960s. He gave his last deposition in 1980, two years before his death.

Morgen once described himself as a Gerechtigkeitsfanatiker – a fanatic for justice. This self-description is true in a sense, but that sense is neither as clear nor as favourable as he thought. Morgen was indeed fanatical about justice as he conceived it, but his conception of justice was not always adequate to the systematic inhumanity that surrounded him. As a specialist in crimes of corruption, he tended to focus on the corrupt character of criminals or their corrupting influence on his organisation, the SS. Though shocked by inhumanity, he was also shocked by impropriety, as well as the deleterious effect of both on the state and its servants.

Thus, when Morgen reported the mass extermination to superiors, his ‘most emphatic and most crucial advice’, he says, ‘was that the SS members who participated in the gassing were thereby so corrupted that they would in future prove no longer serviceable as normal soldiers or even as citizens, and furthermore that the leadership of the state was destroying its own moral foundations with these monstrous crimes’. At a post-war trial he boasts: ‘I am positive as a result of my investigations that I was able to [show] with concrete cases that the agents which were used for the bloody practices became absolutely criminals. Absolute putrid.’

Morgen never doubted that the gassings were ‘monstrous crimes’, but he also looked beyond the horrors suffered by the victims to the damage done to the perpetrators. In short, he sometimes did the right thing for the wrong reasons. He was an equivocal figure, and a case study in moral complexity. His moral and legal reasoning drove him to unique and dangerous acts, but his sense of justice was no match for the extraordinary circumstances of the Third Reich.

This essay is adapted from the authors’ new book Konrad Morgen: The Conscience of a Nazi Judge.