Much has changed in the fantasy genre in recent decades, but the word ‘fantasy’ still conjures images of dragons, castles, sword-wielding heroes and premodern wildernesses brimming with magic. Major media phenomena such as Harry Potter and Game of Thrones have helped to make medievalist fantasy mainstream, and if you look in the kids’ section of nearly any kind of store today you’ll see sanitised versions of the magical Middle Ages packaged for youth of every age. How did fantasy set in pseudo-medieval, roughly British worlds achieve such a cultural status? Ironically, the modern form of this wildly popular genre, so often associated with escapism and childishness, took root in one of the most elite spaces in the academic world.

The heart of fantasy literature grows out of the fiction and scholarly legacy of two University of Oxford medievalists: J R R Tolkien and C S Lewis. It is well known that Tolkien and Lewis were friends and colleagues who belonged to a writing group called the Inklings where they shared drafts of their poetry and fiction at Oxford. There they workshopped what would become Tolkien’s Middle-earth books, beginning with the children’s novel The Hobbit (1937), and followed in the 1950s with The Lord of the Rings and Lewis’s Chronicles of Narnia series, which was explicitly aimed at children. Tolkien’s influence on fantasy is so important that in the 1990s the American scholar Brian Attebery defined the genre ‘not by boundaries but by a centre’: Tolkien’s Middle-earth. ‘Tolkien’s form of fantasy, for readers in English, is our mental template’ for all fantasy, he suggests in Strategies of Fantasy (1992). Lewis’s books, meanwhile, are iconic as both children’s literature and fantasy. Their recurring plot structure of modern-day children slipping out of this world to save a magical, medieval otherworld has become one of the most common approaches to the genre, identified in Farah Mendlesohn’s taxonomy of fantasy as the ‘portal-quest’.

What is less known is that Tolkien and Lewis also designed and established the curriculum for Oxford’s developing English School, and through it educated a second generation of important children’s fantasy authors in their own intellectual image. Put in place in 1931, this curriculum focused on the medieval period to the near-exclusion of other eras; it guided students’ reading and examinations until 1970, and some aspects of it remain today. Though there has been relatively little attention paid to the connection until now, these activities – fantasy-writing, often for children, and curricular design in England’s oldest and most prestigious university – were intimately related. Tolkien and Lewis’s fiction regularly alludes to works in the syllabus that they created, and their Oxford-educated successors likewise draw upon these medieval sources when they set out to write their own children’s fantasy in later decades. In this way, Tolkien and Lewis were able to make a two-pronged attack, both within and outside the academy, on the disenchantment, relativism, ambiguity and progressivism that they saw and detested in 20th-century modernity.

Tolkien articulated his anxieties about the cultural changes sweeping across Britain in terms of ‘American sanitation, morale-pep, feminism, and mass-production’, calling ‘this Americo-cosmopolitanism very terrifying’ and suggesting in a 1943 letter to his son Christopher that, if this was to be the outcome of an Allied Second World War win, he wasn’t sure that victory would be better for the ‘mind and spirit’ – and for England – than a loss to Nazi forces.

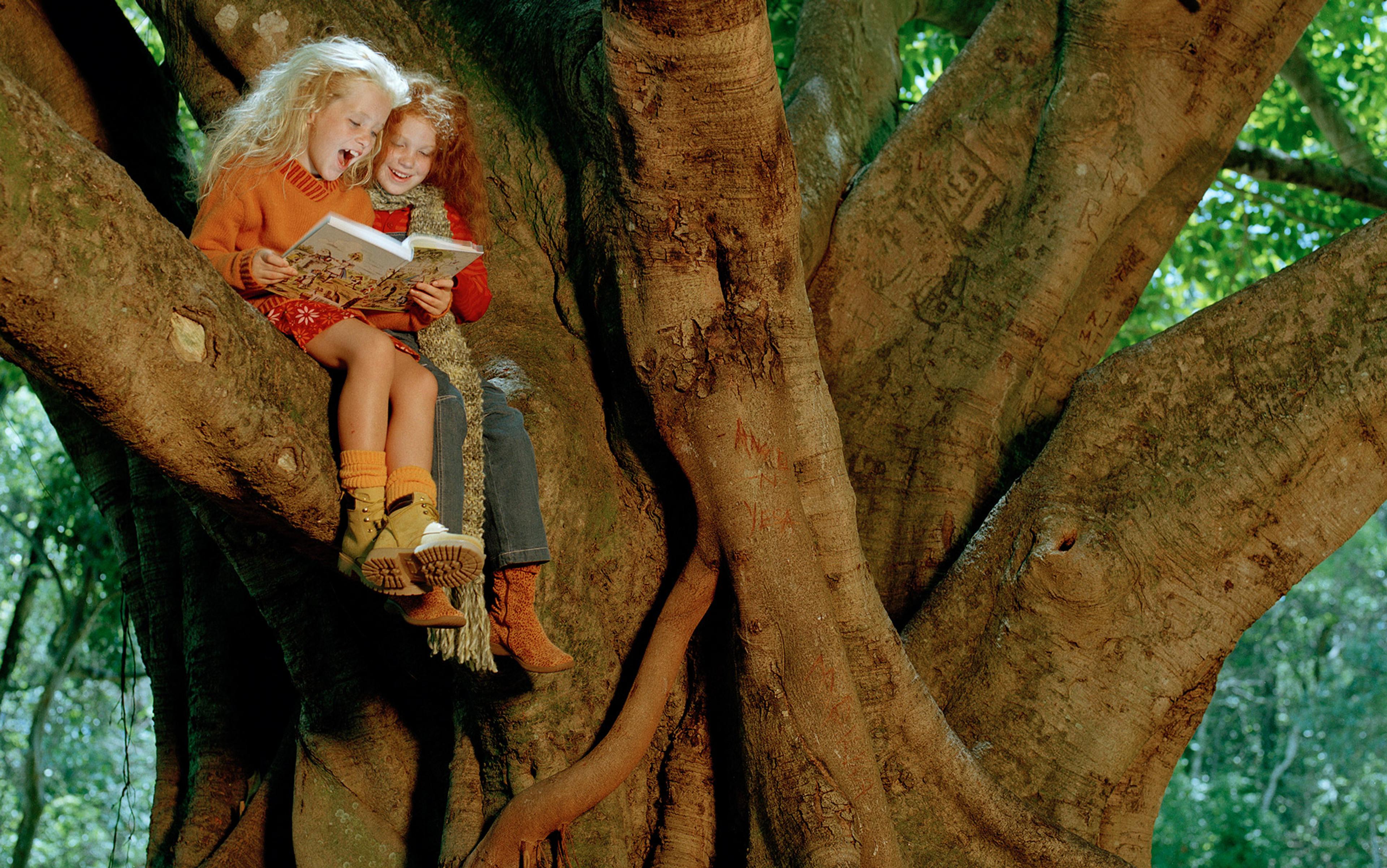

Lewis shared this abhorrence for ‘modern’ technologisation, secularisation and the swiftly dismantling hierarchies of race, gender and class. He and Tolkien saw such broader shifts reflected in changing (and in their estimation dangerously faddish) literary norms. Writing in the 1930s, Tolkien skewered ‘the critics’ for disregarding the fantastical dragon and ogres in Beowulf as ‘unfashionable creatures’ in a widely read essay about that Old English poem. Lewis disparaged modernist literati in his Experiment in Criticism (1961), mocking devotees of contemporary darlings such as T S Eliot and claiming that ‘while this goes on downstairs, the only real literary experience in such a family may be occurring in a back bedroom where a small boy is reading Treasure Island under the bed-clothes by the light of an electric torch.’ If the new literary culture was accelerating the slide to moral decay, Tolkien and Lewis identified salvation in the authentic, childlike enjoyment of adventure and fairy stories, especially ones set in medieval lands. And so, armed with the unlikely weapons of medievalism and childhood, they waged a campaign that hinged on spreading the fantastic in both popular and scholarly spheres. Improbably, they were extraordinarily successful in leaving far-reaching marks on the global imagination by launching an alternative strand of writing that first circulated amongst child readers.

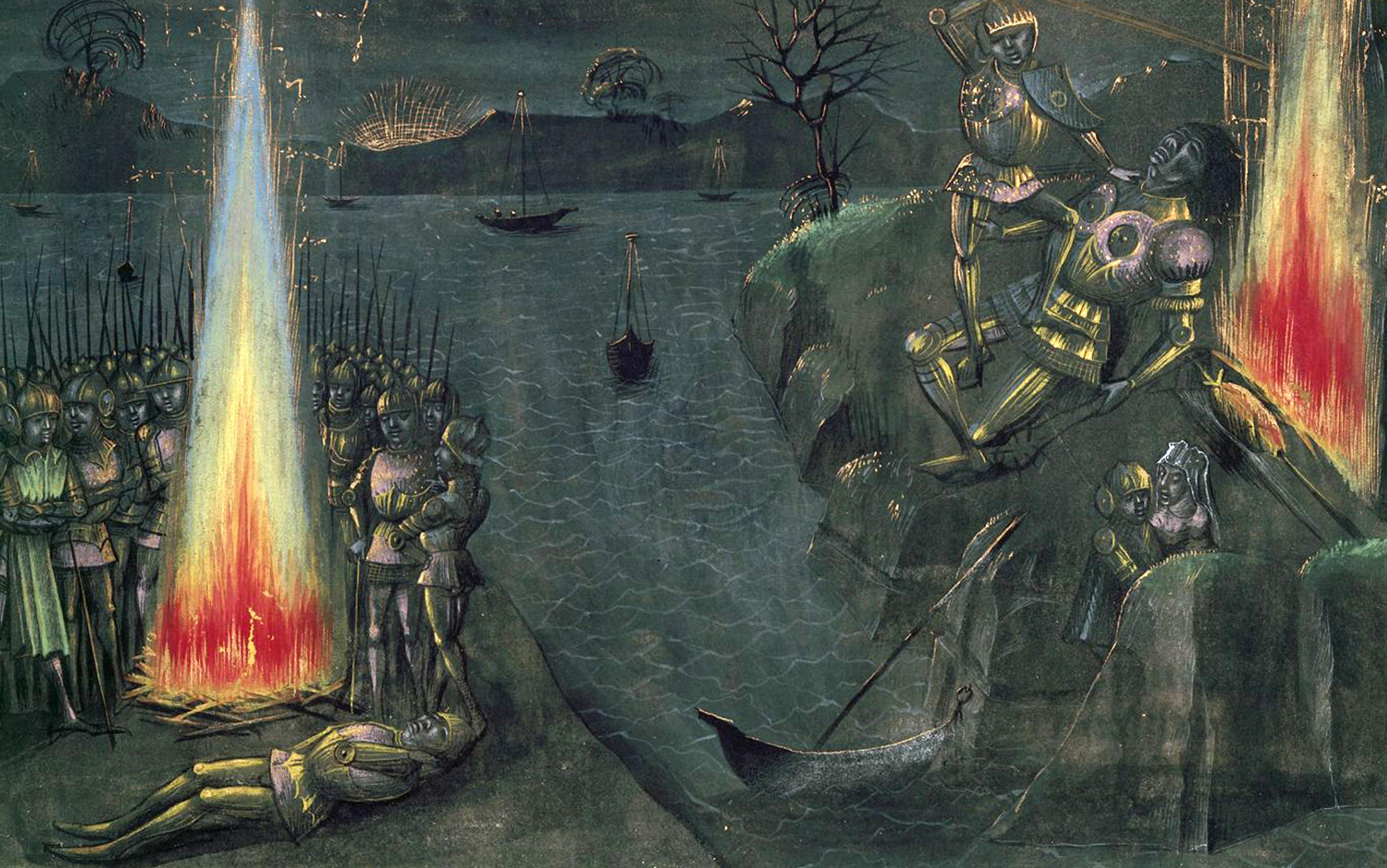

These readers devoured The Hobbit and, later, The Lord of the Rings, as well as The Chronicles of Narnia series. But they also read fantasy by later authors who began to write in this vein – including several major British children’s writers who studied the English curriculum that Tolkien and Lewis established at Oxford as undergraduates. This curriculum flew in the face of the directions that other universities were taking in the early years of the field. As modernism became canon and critical theory was on the rise, Oxford instead required undergraduates to read and comment on fantastical early English works such as Beowulf, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Orfeo, Le Morte d’Arthur and John Mandeville’s Travels in their original medieval languages.

Oxford for nearly 40 years officially sanctioned magic-filled medieval works as exemplars of English literature

Students had to analyse these texts as literature rather than only as linguistic extracts, a notable difference from the more common approach to medieval literature at the time. Tolkien and Lewis identified concrete moral lessons and ‘patriotic’ insights into the national character in these magical tales of long ago. The past they depicted was not, of course, England as it actually was in the Middle Ages, but England as poets had imagined it to be: the enchanted realm of heroism, righteousness and romance where 19th-century nationalists had identified the moral and racial heart of the nation. (The Oxford curriculum was, in this sense, a throwback to English studies’ roots in colonial education, which – as the literary scholar Gauri Viswanathan has shown in Masks of Conquest (2014) – often looked to prove English right to rule through the glory of its national literature.

The unique educational programme that dominated English at Oxford for nearly 40 years officially sanctioned magic-filled medieval works as exemplars of English literature for generations of students that passed through the university’s power-filled halls. And a number of these students went on to write their own popular children’s fantasy, some to great acclaim. Diana Wynne Jones, Susan Cooper, Kevin Crossley-Holland and Philip Pullman in particular, who each received their English degrees between 1956 and 1968, draw on medieval and early modern literary sources, many directly taken from the Oxford syllabus, to create new, self-reflectively serious fantasy for young readers. Together with Tolkien and Lewis, this group forms the Oxford School of children’s fantasy literature. Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising quintet (1965-77) and Crossley-Holland’s Arthur trilogy (2000-03) give King Arthur’s story fresh context and resonance for understanding contemporary Britain in their times; meanwhile, the works of Jones and Pullman delight in subverting fantasy expectations while introducing early English literature to new generations of readers. They all celebrate the purported wisdom of old stories, and follow the central tenet that Tolkien set out for fairy-stories: ‘one thing must not be made fun of, the magic itself. That must in the story be taken seriously, neither laughed at nor explained away.’

The Oxford School’s reimagining of medieval tales for modern audiences injected these fantastical narratives into the public consciousness, largely eluding elite and scholarly notice because their works were branded as children’s literature. At the same time, taking ancient, canonical texts as the foundations for new stories helped to give their fantasy the historical depth and cultural weight to resist derisive laughter and make claims about the present. For instance, the dragon episode at the end of The Hobbit is full of parallels to the one in Beowulf, from the cup-theft that wakes the worm to its destructive expressions of rage. But The Hobbit uses this narrative to pit a traditionalist and noble-born hero (Bard, whose name means ‘poet’, ‘storyteller’) against an untrustworthy elected official, hammering home the significance of conservative traditions over the whims of easily swayed masses. Tolkien’s novel ends with the protagonist Bilbo’s delighted discovery of this barely veiled moral: ‘the prophecies of the old songs have turned out to be true, after a fashion!’

The Oxford School’s medievalist approach radiated outward, influencing many more children’s fantasy authors and readers, and helping to turn Anglophilic fascination with early Britain and its medieval legends into a globally recognisable setting for children’s adventures, world-saving deeds and magical possibility. While Tolkien resisted being categorised as a children’s author, he and Lewis’s turn towards children’s literature as a vehicle for cultural change came at the ideal moment for such a project. As Seth Lerer notes in his history of children’s literature, the child is now ‘a metaphor for much that later periods considered “medieval” in itself’.

Following the spread of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytical theories of development in the early 20th century, childhood took on new significance as the formative seed of adult identity. This concept – combined with the ‘discovery’ by 19th-century thinkers of distinct national roots in early, ambiguously medieval folklore and myth across Northern Europe – had formidable effects. In his essay collection Faith in Fakes (1986), the Italian novelist Umberto Eco claimed that ‘looking at the Middle Ages means looking at our infancy’, an assessment that explains why medieval worlds imbued with the magic associated with Romantic childhood came to be seen as especially appropriate for young people in Western Europe and former colonies.

Children’s literature and the modern conception of childhood, both of which date only to the mid-18th century, have also always been implicitly bourgeois and raced white – making children’s culture particularly fertile ground for nostalgic returns to an enchanted, whitewashed past that celebrates long-held social hierarchies. Meanwhile, Lerer points out, ‘the forms of children’s literature are distinctively pre-modern’; he cites ‘allegory, moral fable, romance, and symbolism’ as narrative devices that dominated medieval literature but gave way to the ‘realism, history, social critique, and psychological depth’ associated with literature for adults following the rise of modernism. However, these forms didn’t disappear; Tolkien argued that they were ‘relegated to the “nursery”’ when they became unfashionable, but remained as valuable as ever for audiences of both children and adults.

White youth in magical realms became the global bread-and-butter of 20th-century children’s culture

The widespread popularity of Tolkien, Lewis and their successors’ medievalist fantasy demonstrated just how receptive 20th-century children’s and pop culture was to writing in this mode. Tolkien and Lewis were in this way able to preserve a dedicated literary space for the magical medievalisms that they valued so highly, even if it didn’t catch on in the ivory tower or adult literary fiction as they’d hoped it would. The Oxford English curriculum seems to have worked most effectively, in that respect, as a training ground for future children’s fantasy writers who carried Tolkien and Lewis’s mission forward in a variety of ways. Indeed, all four of the second-generation Oxford School authors have addressed the role that their fairy-touched undergraduate educations had on their careers: in a talk given in 1997, Jones called the medieval literature she read at Oxford what ‘inspired’ her writing, especially ‘the way writers from the Middle Ages handled narratives. They were all so different, that was the amazing thing, and all so good at it.’

Jones’s numerous novels, which include the Chrestomanci series (1977-2006), the Dalemark quartet (1975-93) and the Derkholm series (1998-2000), show how she also played with old stories, putting them into new contexts to unearth their wisdom for the modern day. Her Howl’s Moving Castle (1986), for example, draws on the ‘loathly lady’ tradition of magical transformation – most famously expressed in ‘The Wife of Bath’s Tale’ by Geoffrey Chaucer – to consider how beauty and age affect women’s freedom and capacity for heroic action. Jones found children’s literature to be the natural outlet for such a project, suggesting that ‘children do, by nature, status, and instinct, live more in the heroic mode than the rest of humanity. They naturally have the right naive, straightforward approach.’ Adult fiction, especially literary fiction following the rise of modernism, seemed to have no such space for such writing.

Pullman has agreed with Jones’s position, claiming in 1996 that in adult literary fiction ‘stories are there on sufferance’, secondary to ‘technique, style, literary knowingness’. He argued that readers ‘still need joy and delight, the promise of connection with something beyond ourselves’, and it might be that ‘children’s literature is the last forum left for such a project.’ Pullman’s conviction echoes Lewis’s Treasure Island claim, even though His Dark Materials – the trilogy that made him famous – counters many of the values that Tolkien and Lewis held dear.

Part of the break with Pullman’s forerunners can be seen in the way that His Dark Materials (1995-2000) and its companion, The Book of Dust trilogy (2017-19), take early modern, not medieval, literature as their primary sources of inspiration – John Milton’s Paradise Lost, on which the original trilogy builds, and Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, which hovers behind the first Book of Dust instalment. Pullman has positioned himself as a Miltonian ‘Satan’ figure in relation to mainstream fantasy in general and Lewis’s Narnia books in particular, out to overturn norms, from the reliance on medieval settings and the privileging of boy characters to the reverence for Christian sentiments that underlie so much of the genre. But while not medieval, Paradise Lost and The Faerie Queene appeared centrally in the Oxford English syllabus. And though Pullman uses them in fantasy that contests Tolkien and Lewis’s conservatism, the Oxford School seriousness about magic and faith in the evergreen wisdom of early English literature remain in his books. So, too, does the Anglocentrism that helped to make the adventures of white youth in magical realms into the globally recognisable bread-and-butter of 20th-century children’s culture.

The legacy of the Oxford School continues into the 21st century with real force. It was on display at the London 2012 Olympic Games’ opening ceremony, which began with a medievalist origin story and dedicated a central section of the multipart show to the magic of British children’s literature. That segment, which featured the author J K Rowling reading from J M Barrie’s Peter Pan, culminates in a battle between a 100ft-tall inflatable Voldemort from her Harry Potter series and a fleet of flying Mary Poppinses from P L Travers’s novels: a magical war over the safety and wellbeing of the pyjama-clad children clustered below. The show repeatedly used magic, medievalism and childhood – the same elements that Tolkien and Lewis brought together to combat encroaching modernity – to claim the enchanted timelessness, international significance and exciting futurity of Britain.

Notably, that opening ceremony leaves empire out of its abridged history of Great Britain, replacing that violent legacy with more benign exports such as children’s fantasy, British pop music and the world wide web. But the stench of empire lingers around much medievalist fantasy; and its gaping absence could still be discerned in the Olympic show’s vision of the nation’s story. It is no coincidence that Oxford School-style fantasy – shaped by two men born in colonial settings (Tolkien in South Africa, Lewis in Ireland) who chose to live in England as adults – took root just as the British empire was coming to an end and Britain confronted a newly reduced role on the global stage. Such works unfold in a magical Middle Ages of youthful English power, bursting with globe-conquering potential. This earlier, fantastical setting allows most fantasy to avoid mentioning histories associated with settler colonisation and transatlantic slavery. But the genre regularly reinforces ideas of racial and moral white supremacy: we see this in Tolkien’s obsession with magical races and dismissal of the dark-skinned, southern-born human Haradrim as evil ‘half-trolls’ in The Lord of the Rings, as well as in Lewis’s orientalist characterisations of the Calormene people in The Chronicles of Narnia. And even in less obviously racist contexts, fantasy often celebrates colonial and xenophobic activities as heroic, with ‘exploring’ and claiming foreign lands abroad and expelling or exterminating unwanted races at home figured as natural parts of innocent, even righteous adventuring.

Knowledge can be found in popular writing that uses magic to explore the outer reaches of the imagination

The spread of fantasy during the 20th century contributed to new ‘empires of the mind’, to repurpose Winston Churchill’s term, a reassertion of British significance displaced into the unthreatening but profoundly influential space of children’s culture. The 2012 Olympics opening ceremony suggests the lasting effects of this move; while colonialism remained an unmentionable chapter, the show could count on global television audiences to join in celebrating the defeat of an undead wizard based on their own investment in a universe of British castles, premodern landscapes, elite boarding-school students, magical creatures and idealised childhood.

The Anglocentrism and whiteness of fantasy literature has gained popular attention in recent years, partially due to the commercial success of the genre and thanks to essential critical works such as Ebony Elizabeth Thomas’s The Dark Fantastic (2019) and Helen Young’s Race and Popular Fantasy Literature (2016). While the popularity of The Lord of the Rings and other medievalist fantasy on white supremacist websites went largely ignored for years, the use of medieval symbols in alt-Right protests has pushed modern-day uses of medievalism into headlines and made the critiques raised by fans, authors and scholars seem more urgent. Publishers, meanwhile, have begun to promote more fantasy inspired by histories and cultures beyond northern Europe – pushed by such conversations and lured by the promise of increased market share as ‘diverse’ fantasy proves lucrative after all. Today, studies of fantasy seem increasingly incomplete unless they address the groundbreaking work of Afrofuturism, Indigenous futurism and their predecessors, as well as other interventions into speculative fiction that break away from European norms and hierarchies in the genre.

Such shifts in attention are long overdue. And yet, at the same time as they are making enormous departures from the foundations of the genre, a great deal of 21st-century fantasy revives and buoys some of the key tenets of the Oxford School. Authors such as Saladin Ahmed, Cherie Dimaline, Zetta Elliott, N K Jemisin, Nnedi Okorafor, Daniel José Older, Sofia Samatar and others rightfully critique the long exclusion of nonwhite voices and diverse ethnic heritages in fantasy, refuse to structure their own works according to medieval English narratives, and decline to set their works in lands that look like Britain. Yet their writing agrees with the Oxford School’s message that how we depict the past for young people is crucially important to present experience, and that profound, world-changing knowledge can be found in popular writing that uses magic to explore the outer reaches of the imagination. In this sense, Tolkien and Lewis’s quest to transform the world by reintroducing old tales has been startlingly successful – and is now being revised, with an equally stunning measure of success, into alternative visions of fantasy that continue to spread, evolve and re-enchant everyday life around the globe.

This essay has been adapted from material published in Re-Enchanted: The Rise of Children’s Fantasy Literature in the Twentieth Century (2019) by Maria Sachiko Cecire.