The only people who hate escapism are jailers, said the essayist and Narnia author C S Lewis. A generation later, the fantasy writer Michael Moorcock revised the quip: jailers love escapism — it’s escape they can’t stand. Today, in the early years of the 21st century, escapism — the act of withdrawing from the pressures of the real world into fantasy worlds — has taken on a scale and scope quite beyond anything Lewis might have envisioned.

I am a writer and critic of fantasy, and for most of my life I have been an escapist. Born in 1977, the year in which Star Wars brought cinematic escapism to new heights, I have seen TV screens grow from blurry analogue boxes to high-definition wide-screens the size of walls. I played my first video game on a rubber-keyed Sinclair ZX Spectrum and have followed the upgrade path through Mega Drive, PlayStation, Xbox and high-powered gaming PCs that lodged supercomputers inside households across the developed world. I have watched the symbolic language of fantasy — of dragons, androids, magic rings, warp drives, haunted houses, robot uprisings, zombie armageddons and the rest — shift from the guilty pleasure of geeks and outcasts to become the diet of mainstream culture.

And I am not alone. I’m emblematic of an entire generation who might, when our history is written, be remembered first and foremost for our exodus into digital fantasy. Is this great escape anything more than idle entertainment — designed to keep us happy in Moorcock’s jail? Or is there, as Lewis believed, a higher purpose to our fantastical flights?

Fans of J R R Tolkien line up squarely behind Lewis. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (1954) took the fantasy novel — previously occupied with moralising children’s stories — and created an entire world in its place. Middle Earth was no metaphor or allegory: it was its own reality, complete with maps, languages, history and politics — a secondary world of fantasy in which readers became fully immersed, escaping primary reality for as long as they continued reading. Immersion has since become the mantra of modern escapist fantasy, and the creation of seamless secondary worlds its mission. We hunger for an escape so complete it borders on oblivion: the total eradication of self and reality beneath a superimposed fantasy.

Language is a powerful technology for escape, but it is only as powerful as the literacy of the reader. Not so with cinema. Star Wars marked the arrival of a new kind of blockbuster film, one that leveraged the cutting edge of computer technology to make on-screen fantasy ever more immersive. Then, in 1991, with James Cameron’s Terminator 2: Judgment Day, computer-generated imagery (CGI) came into its own, and ‘morphing’ established a new standard in fantasy on screen. CGI allowed filmmakers to create fantasy worlds limited only by their imaginations. The hyperreal dinosaurs of Jurassic Park (1993) together with Toy Story (1995), the first full-length CGI feature, unleashed a tidal wave of CGI blockbusters from The Matrix (1999) to Avatar (2009). The seamless melding of reality and fantasy that CGI delivers has transformed our expectations of cinema, and fuelled a ravenous appetite for escape.

The world is not made of atoms. It is made of the stories we tell about atoms

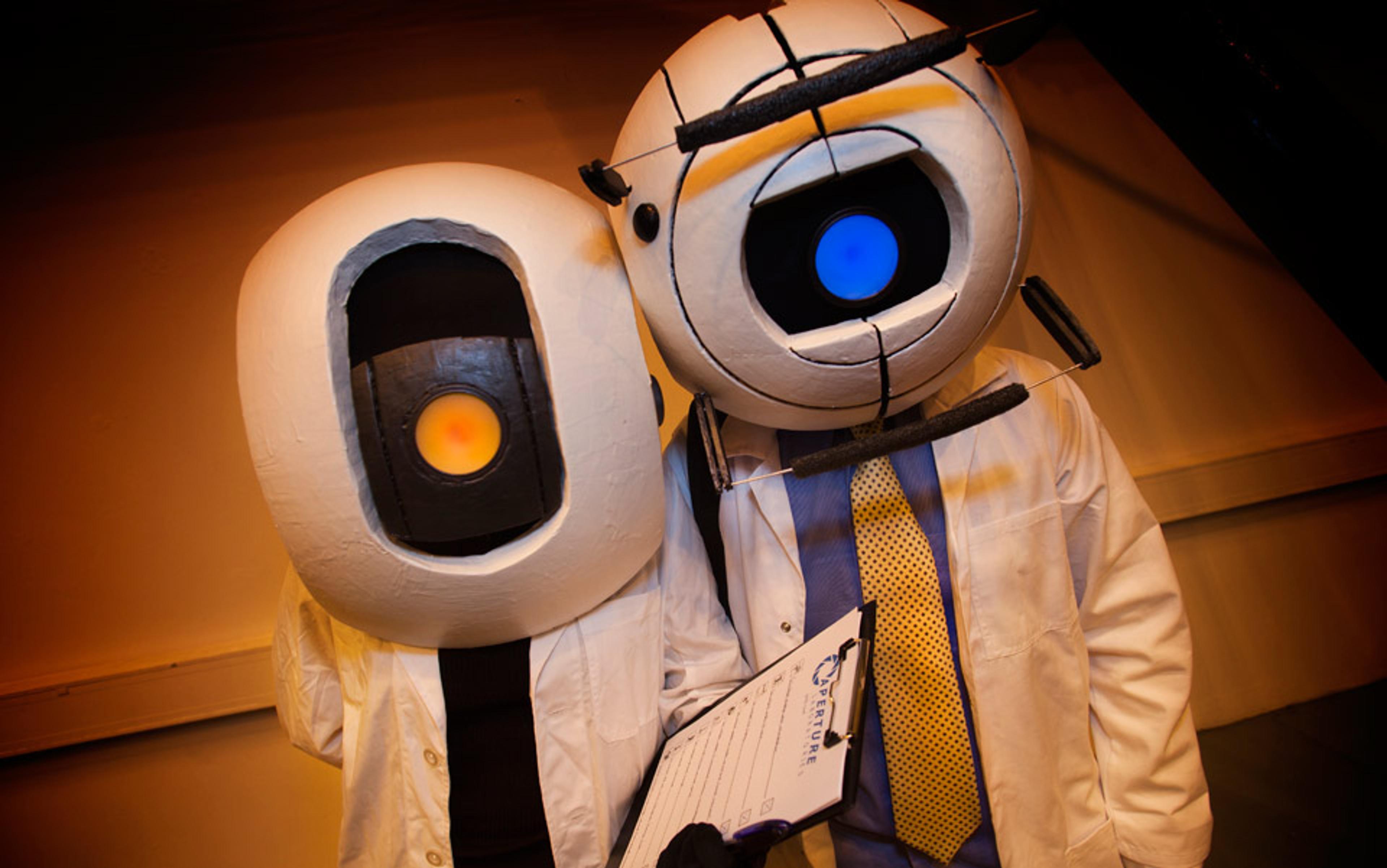

Video games might have seemed an unlikely escapist technology in the early days of Pong and Pac-Man. It takes a mighty effort of will to see the collection of pixels hovering at the bottom of the screen in Space Invaders as the last star-fighter of mankind. But the working of Moore’s Law — which holds that computing power doubles every two years — meant that, by the early 1990s, video games were jockeying with film to lead the escapism industry. That decade also saw the first waves of cyber-utopianism, although the early promise of virtual reality headsets and internet multi-user domains failed to materialise. Instead, it was our thumbs that did the talking through the control pads of home games consoles with high-definition screens. Super Mario Bros, Sonic the Hedgehog and Lara Croft as Tomb Raider helped to transform video games from childish obsession to mainstream cultural phenomenon.

Today, video-game franchises such as Halo, Grand Theft Auto and Call of Duty power an industry worth an estimated $65 billion globally in 2011. But money is only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to measuring the impact of gaming on contemporary culture and society at large. The American video-game designer and researcher Jane McGonigal estimates that there are 500 million ‘virtuoso gamers’ (people who have spent more than 10,000 hours in game worlds) active today. She argues that this number will increase threefold over the next decade: around a fifth of the world’s population will spend as much time in digitally generated worlds as they do in full-time education. We’re embarking on a daring social experiment: the immersion of an entire generation into digitally generated escapist fantasies of unprecedented depth and complexity. And the most remarkable aspect of this potential revolution is how little consideration we are giving it.

As the technology of escape continues to accelerate, we’ve begun to see an eruption of fantasy into reality. The augmented reality of Google Glass, and the virtual reality of the games headset Oculus Rift (resurrected by the power of crowd-funding) present the very real possibility that our digital fantasy worlds might soon be blended with our physical world, enhancing but also distorting our sense of reality. When we can replace our own reflection in the mirror with an image of digitally perfected beauty, how will we tolerate any return to the real? Perhaps, in the end, we will find ourselves, not desperate to escape into fantasy, but desperate to escape from fantasy. Or simply unable to tell which is which.

Some might argue we are already there. In the sci-fi visions of the American futurist Ray Kurzweil and other prophets of post-humanism, we will upload our minds to silicon substrates, there to be accelerated into super-intelligence and the looming technological singularity. It’s a vision of religious communion now widely parodied as ‘The Rapture of the Nerds’.

And yet the digital technologies of today are just the latest in a long progression of tools for the expression of the imagination. We are escaping, not into other worlds, but into imagination. The question is, what are we escaping from? Is it reality? (Whatever that is.)

Philosophers have argued for millennia about the nature of reality, an argument that can be broadly classified within two schools of thought: materialism and idealism. Materialist philosophies contend that reality is composed of matter and energy, and that all observable phenomena, including mind and consciousness, arise from material interactions. For many of us, materialism is the only theory of reality that can or should be given any credence: it underlies all of the scientific and rationalist perspectives prevalent in the world today. What is reality made of, if not atoms, or their constituent particles?

Idealists, meanwhile, take their cues elsewhere. ‘The world is made of stories, not of atoms,’ said the American poet Muriel Rukeyser in 1968. Her words are a powerful expression of a world-view that materialism cannot accommodate. Idealism argues that reality is constructed by the mind. Consciousness does not arise from material interactions, it is universal; and from consciousness arise all of the material phenomena in the universe, including atoms. The world is not made of atoms. It is made of the stories we tell about atoms.

In material philosophy, the act of escaping into our imagination is at best a temporary retreat from reality into fantasy. But in the idealist view, the same act of imagination can reshape our reality.

In the modern world, the argument between materialism and idealism has manifested most powerfully in the opposition between science and religion. Science currently has the upper hand, less because of abstract philosophical arguments than because the huge material benefits of science and technology — tangible products of the Age of Reason — have established a materialist world-view as the de facto belief of almost all citizens of the technologically developed world. Moreover, the Western culture of materialist consumer capitalism is subsuming, through globalisation, all the diverse cultures of our world. The dominant global monoculture is a culture of materialism.

We see in the New Atheist arguments of Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett a triumph of materialist philosophy so complete that even its opponents argue on its terms. God has no place in materialism. There is no higher being of matter and energy responsible for creating matter and energy. The religious fundamentalists who attempt to answer the sceptical claims of New Atheism are themselves rooted in a materialist world-view, leaving a rearguard of idealists to argue, weakly, that God is just a very old word for consciousness and imagination.

Idealism has fared better in the arts, where existentialism and postmodernism have attempted to reinstate imagination at the centre of reality. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s system of deconstruction, for example, returns us to the idea of reality as a construct that must be broken down to its basic building blocks in language before it can be understood. But while such ideas have dominated academic studies of the arts and humanities, they hold little sway beyond those strongholds.

The materialist society of 1980s Britain had a hierarchy, and we were the bottom-rung

It is in the popular culture of escapist fantasy that idealism has been reborn, and imagination re-established its footing. When the American comic book writer Stan Lee was looking for ideas for Marvel stories that would ignite the imagination of kids in 1960s America, the gods of ancient myth and legend became a natural source of inspiration. Beside resurrected Norse gods such as Thor and Loki, Lee created a new pantheon of super-powered heroes to entertain his audience. Decades later, the modern gods Spider-Man, Iron Man, Wolverine and Captain America dominate the silver screen, attracting audiences in their millions to worship in the darkened temples of cinemas. And when the director George Lucas set out to make Star Wars, he built it around the American mythographer Joseph Campbell’s ‘monomyth’ — a distillation of the essential values of thousands of religious stories from around the world.

There is a long tradition of British writers for whom the resurrection of spiritual myths forms the heart of their own ‘mythopoeic’ work. C S Lewis’s mythology was rooted in Christian allegory, while Tolkien delved back further into the mythic history of the British Isles to a landscape of magic and witchery that has since inspired J K Rowling. Thanks to Harry Potter, there is a generation of children and young adults for whom the ancient rituals of magic are as much a part of life as video games. One of this summer’s most anticipated novels was Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane, billed as a fairy tale for grown-ups. From his The Sandman comic-book series to his novel American Gods (2001), Gaiman has made something of a specialism of refitting the world’s mythologies to contemporary culture.

There’s a deep irony in the fact that our rational, secular society, driven by science and technology, is emptying out its churches only to reconstruct them as cinemas. Replacing the ‘good book’ with films about Harry Potter and hunger games; reconstructing the inner worlds of our imagination — once the realm of prayer and ascetic meditation — inside the digital domain of computers: it seems that no matter how hard we try to convince ourselves that reality is only material, we continue to reach for the ideal forms that lie beyond. Are we simply recasting age-old delusions for the modern era?

The reality I was escaping from as a child was a housing estate in the London commuter belt. A cluster of low-rise tower blocks and prefab houses thrown up, like hundreds of other sink estates around the country, for the swelling population of post-war Britain. By the 1980s, estates had become home to the nation’s burgeoning underclass. Work was disappearing to other countries, in a process of globalisation that is still accelerating today. The social policies of the welfare state, public housing, education and health, which had helped to make Britain more equal, were being unwound by a Thatcherite government whose only interest in the poor was as a flexible workforce.

None of which was easily knowable to the youth of Britain’s housing estates. But we could see a simpler truth. On our TV screens and in the shopping centres was the abundant material wealth of consumer capitalism: but it wasn’t for us. Just a few streets away were the suburban homes of middle-class workers. Those weren’t for us either. And the gated communities of the truly wealthy, their country clubs and luxury hotels, were as good as invisible. The hints of them that we did manage to see made it abundantly clear that these weren’t for us either. The materialist society of 1980s Britain had a hierarchy, and we were the bottom-rung.

From the perspective of the underclass, material reality is bleak. You’re a survivor of blind evolution, stranded on a muddy rock under the harsh glare of a nuclear sun. Beyond that is an infinite universe of inert matter, dust and devastating radiation that is neither for nor against you, but simply unaware of your existence. There is no God. There is no heaven, or eternal reward. There is only another shift in the factory, or the call centre, or McDonald’s — if you’re lucky. At its determinist extreme, materialist philosophy enforces a strikingly rigid and oppressive social hierarchy.

Faced with your own inferiority in this hierarchy, why wouldn’t you plunge into fantasy? Invest your hopes in the teleporter caprices of reality TV, where faux victory in The X Factor or The Apprentice can raise you to the neon-lit stratosphere of celebrity. Light up a spliff and switch on your Xbox. Lose yourself in the colourful pages of comic books. Fulfil your dreams of being beautiful, wealthy, heroic — the centre of a universe built just for you! — and ignore the world beyond your bedsit, in which you are underpaid, unloved and anonymous. But all the while these escapist fantasies are fed by an industry that seeks merely to commodify our dreams and then sell them back to us, stripped of meaning, emptied of the true potential of human imagination. We remain in jail, only dreaming of freedom.

The real lesson that poverty teaches is that our society is shaped for those with power. Yet in this, paradoxically, there might still be some hope for our great escape, because all escapism takes us to worlds created through an act of imagination. Hour after hour, we practise what it means to be creators of our own worlds: through the empowered actions of heroes such as Luke Skywalker, or The Terminator’s Sarah Connor; through the creation of our own heroes in games such as World of Warcraft; or even by exploring our own God-like creativity in SimCity or Minecraft.

Do our fantasy worlds, then, help us to escape, not from reality, but from our own limitations? Is it possible that we might bring back from our escapist adventures a renewed sense of our own power and creative potential as human beings? In a world that demands ever more of both, this could the highest function of escapism, and the calling that we should demand of it.