Listen to this essay

25 minute listen

‘I imagine that one of the reasons people cling to their hates so stubbornly is because they sense, once hate is gone, that they will be forced to deal with pain.’

– from Notes of a Native Son (1955) by James Baldwin

Some people seem driven more by what they oppose, reject and hate than by what they promote, affirm and revere. Their political commitments, personal identities and emotional lives appear to be structured more by opposition, resentment and hostility than by a positive set of ideals or aspirations.

Tucker Carlson, a prominent Right-wing television host and former Fox News anchor, has no shortage of enemies. On his shows, he has condemned gender-neutral pronouns, immigrants, the removal of Confederate statues, mainstream media, the FBI and CIA, globalism, paper straws, big tech, foreign aid, school curricula, feminism, gingerbread people, modern art – and the list goes on. Each item is presented as an existential threat or a sign of cultural decay. Even when conservatives controlled the White House and the US Senate, he presented those like him as under siege. Victories never brought relief, only more enemies, more outrage, more reasons to stay aggrieved.

In April 2025, Donald Trump took the stage to mark the 100th day of his second term as US president. You might have expected a moment of triumph. He had reclaimed the presidency, consolidated power within the Republican Party, and issued a vast range of executive orders. But the mood wasn’t celebratory. It was combative. Trump spent most of his time attacking his predecessor Joe Biden, repeating false claims about the 2020 election, denouncing the press, and warning of threats posed by immigrants, ‘radical Left lunatics’ and corrupt elites. The tone was familiar: angry, aggrieved, unrelenting. Even in victory, the focus was on enemies and retribution.

This dynamic isn’t unique to the United States. Leaders like Narendra Modi in India, Viktor Orbán in Hungary and Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil have built movements that thrive on perpetual grievance. Even after consolidating power, they continue to cast their nations as under siege – from immigrants, intellectuals, journalists or cultural elites. The rhetoric remains combative, the mood aggrieved.

Figures like Carlson and Trump don’t pivot from grievance to resolution. Victory doesn’t bring peace, grace or reconciliation. Instead, they remain locked in opposition. Their energy, their meaning, even their identity, seem to depend on having an endless list of enemies to fight.

So there’s an interesting dynamic: certain individuals and movements seem geared toward perpetual opposition. When one grievance is corrected, another is found. When one enemy is defeated, another is sought. What explains this perpetual need for enemies?

Some people adopt this stance tactically: they recognise that opposition and condemnation can attract a large following, so they produce outrage or encourage grievance as a way of generating attention. Perhaps it’s all an act: what they really want, what they really care about, is maximising the number of social media followers, building brands or getting elected. But this can’t be a full explanation. Even if certain people adopt this tactical stance, their followers don’t: they appear genuinely gripped by anger and condemnation. And not all leaders appear to be calculating and strategic: Trump’s outrage is genuine.

This pattern of endless denunciation and grievance has been noticed by many scholars. As a recent study puts it, ‘grievance politics revolves around the fuelling, funnelling, and flaming of negative emotions such as fear or anger.’ But what makes this oppositional stance appealing? If it’s not just strategic posturing, what explains it? We can begin answering that question by distinguishing two ways that movements or orientations can be oppositional.

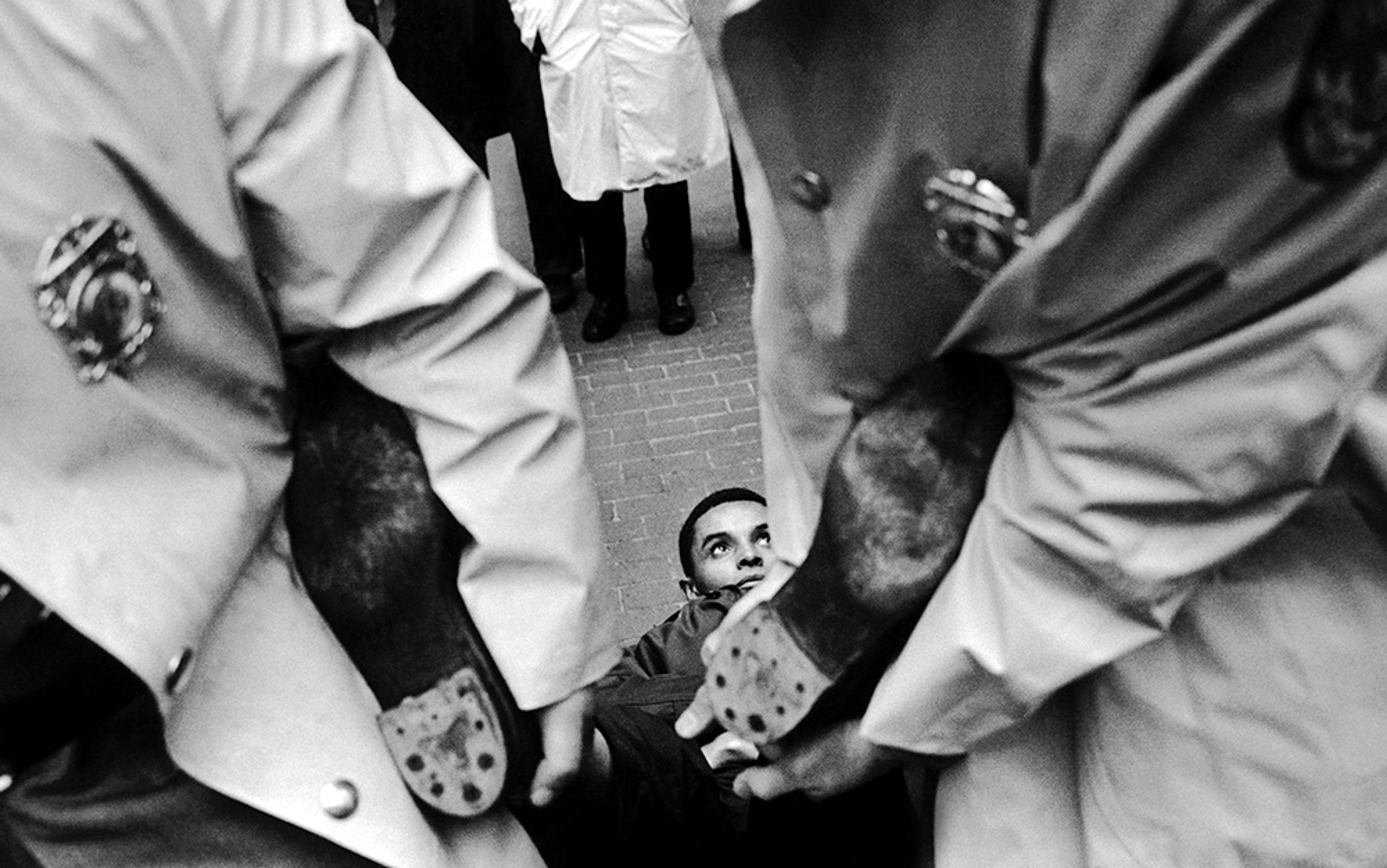

Sometimes, movements face a vast set of obstacles and opponents. Take the protests against the Vietnam War in the 1960s and ’70s. This movement had a clear goal: ending US involvement in Vietnam. It lasted for more than a decade and unfolded across multiple fronts, which ranged from marches to acts of civil disobedience to teach-ins to draft resistance. Participants faced real costs: jail time, government surveillance, public backlash, even violence. The targets of opposition shifted over time – from the Lyndon B Johnson administration, to Richard Nixon, to Gerald Ford. The tactics evolved: from letter-writing campaigns to draft-card burnings, mass marches, lobbying from wounded veterans, and testimony from grieving families. Nonetheless, this was a movement that aimed at a concrete goal. Opposition was necessary, but it was a means to an end. The focus remained on the goal, rather than on sustaining conflict for its own sake.

The anti-apartheid movement offers another example. For decades, activists fought to dismantle a specific political system in South Africa. The struggle demanded great sacrifice and long-term opposition, but these efforts were tethered to a definite goal. Once that goal was achieved, the movement largely dissolved. Its antagonism had a purpose and, when that purpose was fulfilled, the opposition faded.

What’s essential is the continuous expression of hostility, rather than the attainment of any particular goal

The Vietnam War protests and the anti-apartheid movements both involved forms of opposition and grievance, but their antagonism was in the service of positive goals. The movements discussed above – those led by Carlson, Trump, Orbán and so on – are very different. Their energy, coherence and sense of identity seem to depend on opposition itself. Grievance animates their followers; hostility to enemies becomes central to how they think, feel and see themselves. Without enemies, the movement would unravel.

These examples indicate that hostility, anger and opposition don’t necessarily make a movement problematic. On the contrary, they can be signs of moral concern, legitimate reactions to the fact that something precious is being threatened. As Martha Nussbaum has argued, anger can play an essential role in democratic life by expressing moral concern and galvanising collective action. Iris Marion Young has made similar points, showing how opposition can affirm shared values. And in 1968 Martin Luther King Jr claimed that ‘the supreme task is to organise and unite people so that their anger becomes a transforming force.’ But there’s a difference between opposition that aims to realise a shared good, and opposition that is pursued for its own sake. Some movements use opposition as a means to build something they value. Others make opposition itself the point. That’s the distinction I want to highlight: between what I call contingently negative and constitutively negative orientations. Contingently negative movements treat opposition as a means to a positive end, a way of building something better. Constitutively negative movements are different: what’s essential is the continuous expression of hostility, rather than the attainment of any particular goal.

Grievance politics involves a constitutively negative orientation. That’s what sets it apart from liberatory movements, struggles to realise ideals, or efforts to defend cherished values. If you value something, you’ll be disturbed by threats to it. You’ll be sensitive to people who might undermine it, and you may be moved to defend it. That’s normal. That’s part of what it is to value anything at all. But constitutively negative orientations are different. Values are just pretexts for expressing hostility. If one value is secured, we just need a new outlet and a new justification for hostility. The driving need is not to protect or preserve, but to oppose.

But why would anyone be drawn to a constitutively negative orientation? Why are these orientations so gripping? The answer is simple: they deliver powerful psychological and existential rewards. Psychologically, they transform inward pain to outward hostility, offer a feeling of elevated worth, and transform powerlessness into righteousness. Existentially, they provide a sense of identity, community and purpose.

To see how this works, we need to distinguish between emotions and emotional mechanisms. Emotions like anger, hatred, sadness, love and fear are familiar. But emotional mechanisms are subtler and often go unnoticed. They are not individual emotions; they’re psychological processes that transform one emotional state into another. They take one set of emotions as input and produce a different set of emotions as output.

Here’s a familiar example: it’s hard to keep wanting something that you know you can’t have. If you desperately want something and can’t get it, you will experience frustration, unease, perhaps envy; you may even feel like a failure. In light of this, there’s psychological pressure to transform frustration and envy into dismissal and rejection. The teenager who can’t make it onto the soccer team convinces himself that athletes are just dumb jocks. Or, you’re filled with envy when you scroll through photos of exotic vacations and gleaming houses, but you reassure yourself that only superficial people want these things – your humble home is all that you really want.

Friedrich Nietzsche photographed in 1882 by Gustav Adolf Schultze. Courtesy Wikipedia

There’s a similar mechanism that transforms humiliation and low self-worth into a form of spiteful hatred. Philosophers call this ressentiment – a French word for resentment, but with a twist. It names not just a passing feeling, but a deeper emotional mechanism, one that transmutes pain, powerlessness and humiliation into condemnation. In the late 19th century, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that ressentiment is the emotional mechanism behind many of our values. Modern ‘morality begins’, Nietzsche wrote in On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), ‘when ressentiment itself becomes creative and gives birth to values.’ Since then, a range of thinkers have traced the way that ressentiment shapes social and political life. As Wendy Brown describes it, ressentiment is a ‘triple achievement: it produces an affect (rage, righteousness) that overwhelms the hurt, it produces a culprit responsible for the hurt, and it produces a site of revenge to displace the hurt …’ Put simply, ressentiment is an emotional mechanism that transforms feelings of worthlessness or humiliation into vindictive feelings of superiority, rancour and blame.

His sadness transforms into anger. He has enemies to rail against and grievances to voice

We can see how this plays out in individual lives. Imagine someone who grows up in a declining rural town. She dreams of escape, fantasising about the vibrant lives she sees portrayed in cities, lives full of culture, opportunity, wealth and success. As the years go on, the dream seems unattainable. Jobs are scarce, advancement elusive, and nothing in her life resembles what she once imagined. Frustrated and unhappy, she feels like a failure in life. But then she encounters grievance-filled populist rhetoric. The people she once admired and envied – the people she now identifies as the urban elite – are cast as the cause of her suffering. They are selfish, out of touch, morally corrupt, and hostile to her way of life. What once seemed like an image of the good life now appears as injustice. And, rather than focusing on specific policy proposals for correcting structural economic injustices, she becomes energised by condemnation and hostility.

Or picture another person, a lonely man who watches others form friendships, build relationships, and move easily through social spaces, while he remains on the margins. He feels isolated, sad, alone. One day he stumbles into a corner of the internet that offers an explanation: the problem isn’t him, it’s the world. Reading incel websites, he comes to believe that feminism, social norms and cultural hypocrisy have made genuine connection impossible for someone like him. In time, he internalises this story. His disappointment becomes a source of pride, a mark of insight. His sadness transforms into anger. He has enemies to rail against and grievances to voice.

These cases differ in an interesting way: the economic case involves a real form of structural injustice, whereas the incel case involves an ideology that invents a grievance. But notice that beyond this difference, there’s a similar emotional arc. A person starts out with a positive vision of the good. But their life is full of hardship, disappointment and despair. Initially, they might blame themselves. And that’s painful. It’s hard to sit in one’s own pain, feeling responsible for it, feeling like a failure. It’s especially hard when you see other people enjoying the life that you wish you had.

In time, these people encounter a narrative that redirects the blame. Their unhappiness isn’t their own fault, it’s the fault of someone else. They are being treated unfairly, unjustly; they are being attacked, oppressed or undermined. This kind of story is seductive. It offers release from feelings of diminished self-worth. It offers a way to deflect pain, assign blame and recast oneself as a victim. It also offers a community of like-minded peers who reinforce this story. What emerges is a kind of negative solidarity: bound together through animosity, they attack or disparage an outgroup. The individual now belongs to a group of people who share outrage and recognise the same enemies. The chaos and turmoil of life is organised into a clear narrative of righteousness: in opposing the enemy, we become good.

As the 20th-century thinkers René Girard and Mircea Eliade remind us, opposition can do more than divide – it can bind. Girard saw how communities forge unity through a common enemy, channelling their fears and frustrations onto scapegoats. This shared act of condemnation offers not just relief, but belonging. Eliade, approaching these points from a different angle, examined our yearning to fold personal suffering into a larger, morally charged drama. Grievance politics draws on both patterns. It doesn’t just vent rage; it weaves pain into a story. It offers a script in which hardship becomes injustice, and outrage becomes identity.

These patterns aren’t just speculative. Scholars have traced how pain, disappointment and a sense of failure can be transfigured into grievance – how personal frustration becomes political identity. In her work on rural Wisconsin, Katherine Cramer shows how economic stagnation can give rise to resentment toward urban elites. Arlie Russell Hochschild, drawing on interviews in Louisiana, describes a ‘deep story’ in which people feel passed over, displaced, left behind. Kate Manne and Amia Srinivasan examine how narratives in incel communities convert rejection and loneliness into a sense of moral entitlement. And a wide range of research in psychology, sociology and philosophy explores how diminished self-worth can be redirected outward: into anger, blame and opposition.

The most effective narratives are superficially plausible. But they tend to be exaggerated and simplistic

When movements are formed and sustained in this way, they are no longer organised around a shared vision of the good. Instead, they are structured by shared animosity. Opposition isn’t incidental. It becomes the structure through which meaning, coherence and solidarity are generated.

Often, these narratives begin with real problems and legitimate grievances – the economic case certainly does. The most effective narratives are superficially plausible. But they tend to be exaggerated and simplistic. It may be true that economic opportunities are scarce and financial security is precarious. But the ressentiment narrative turns this into a story of blame and hostility, painting a simple picture of who is responsible and what can be done about it. It transforms genuine frustration into wholesale animosity.

And that’s why these movements need enemies. They define themselves through rejection. Unlike contingently negative orientations – which are built around the pursuit of some good, some value worth realising – constitutively negative orientations draw their energy from resistance, antagonism and negation. Their integrity depends on the persistence of something to oppose. The result is a kind of political metabolism that requires enemies to function. If the enemy disappears, the orientation loses its shape.

This is not simply a matter of having enemies, which is common to many political movements. Nor is it a criticism of all forms of opposition; many just causes require resistance and a focus on enemies. The key point is structural: in constitutively negative orientations, opposition is pursued for its own sake. Opposition is no longer a means to an end; it is the end itself. Resolution becomes a threat rather than a goal, for resolution would rob the movement of the very antagonism that gives it purpose.

Viewed in this light, the Carlson monologues and Trump rallies aren’t simply strategic or performative. They’re sustaining a structure of belonging built around the rhetoric of attack. What the movements share is an inability to rest, to consolidate, to affirm. They live through negation.

With all of that in mind, we can now see the structure of grievance politics more clearly. In the traditional picture, grievance begins with ideals. We have definite ideas about what the world should be like. We look around the world and see that it fails to meet these values, that it contains certain injustices. From there, we identify people responsible for these injustices, and blame them.

But grievance politics operates differently. It begins not with ideals, but with unease, with feelings of powerlessness, failure, humiliation or inadequacy. Political and ethical rhetoric is offered that transforms these self-directed negative emotions into hostility, rage and blame. Negative emotions that would otherwise remain internal find a new outlet, latching on to ever-new enemies and grievances. The vision that redirects these emotions will cite particular values and goals, but the content of those values and goals doesn’t matter all that much. What’s most important is that the values and goals justify the hostility. If the world changes, the values and ideals can shift. But the emotional need remains constant: to find someone or something to oppose.

That’s why traditional modes of engagement with grievance politics will backfire. People often ask: why not just give them some of what they want? Why not compromise, appease or meet them halfway? Surely, if you satisfy the grievance, the hostility will subside?

Devotion is capable of bringing deep, serene fulfilment without requiring an enemy

But it doesn’t. The moment one demand is met, another appears. The particular goals and demands are not the point. They are just vehicles for expressing opposition. What’s really being sustained is the emotional orientation: the need for enemies. Understanding grievance politics as a constitutively negative orientation – as a stance that draws its energy and coherence from opposition itself – changes how we respond. It explains why fact-checking, appeasement and policy concessions fail: they treat symptoms, rather than the cause. If opposition itself is the source of emotional resolution and identity, then resolution feels like a loss rather than a gain. It drains the movement’s animating force. That’s why each appeasement is followed by a new complaint, a new enemy, a new cause for outrage. The point is not to win; the point is to keep fighting and condemning.

Seeing the dynamic in this way also clarifies what real resistance would require. The aim isn’t just to rebut false claims, to condemn hostility or to attempt appeasement. The solution is to redirect the energies that grievance politics mobilises. To do so, we need alternative forms of meaning, identity and belonging, which satisfy those needs in a way that doesn’t depend on hostile antagonism. We need an orientation that is grounded not in grievance, but in affirmation. One that draws strength not from hostility, but from commitment to something worth loving, revering or cherishing.

What we need, then, are narratives that can sustain devotion. Devotion is a form of attachment that combines love or reverence with commitment and a willingness to endure. It orients a person toward something they regard as intrinsically worthwhile – something that gives shape to a life, even in the face of difficulty or doubt. Like constitutively negative orientations, devotion can provide identity, purpose and belonging. But it does so without requiring an enemy. Its energy comes not from opposition, but from fidelity to a value that’s seen as worthy of ongoing care.

In my own work, I’ve argued that devotion can supply a stable sense of meaning, identity and purpose, without lapsing into antagonism and dogmatism. This picture resonates with Josiah Royce’s claim that loyalty – which he understands as a form of devotion – provides ‘a personal solution of the hardest of human practical problems, the problem: “For what do I live? Why am I here? For what am I good? Why am I needed?”’ It aligns with Harry Frankfurt’s claim that a person’s life is meaningful only if it is devoted to goods that the person cares about for their own sake, and with Thomas Aquinas’s observation that ‘the direct and principal effect of devotion is the spiritual joy of the mind …’ Devotion, so understood, is a steadfast responsiveness to what we cherish, capable of bringing deep, serene fulfilment without requiring an enemy.

Of course, offering devotion as an alternative to grievance politics does not mean dismissing all grievances. Many forms of suffering and injustice – economic inequality, systemic racism, political exclusion – warrant deep frustration and sustained protest. To feel aggrieved in the face of real harm is not pathological; it is often morally appropriate. Anger, complaint and critique are vital political tools. What makes grievance politics problematic is not the presence of complaint, but the constitutively negative orientation. Grievance politics is not rooted in a desire to repair or transform, but in a need to oppose. The problem isn’t the grievance itself – the problem is when perpetual grievance becomes the whole point, and opposition displaces aspiration.

Grievance politics offers coherence, energy and a sense of belonging. But it does so by centring life around perpetual opposition. Its psychological and existential satisfactions are real, but profoundly damaging. When identity is built through antagonism, it becomes dependent on conflict. And that means it can’t stop; it can’t rest. The deeper challenge, then, isn’t just to rebut its claims or counter its policies. It’s to offer orientations that can sustain identity, meaning and solidarity without requiring an endless sea of enemies. That’s a harder task – but it’s the only hope for combatting the politics of grievance.