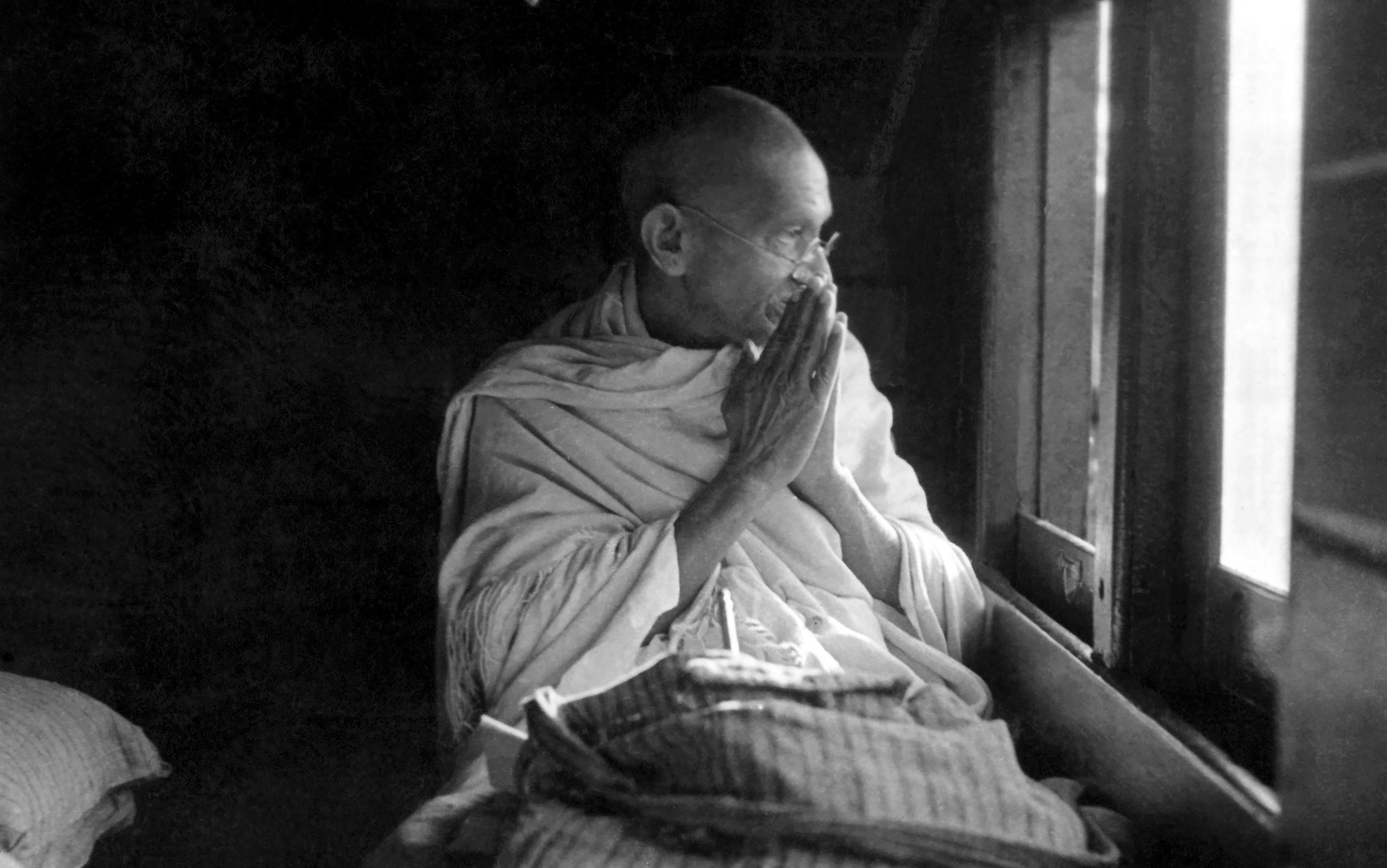

No political action seems to enjoy greater moral authority than the nonviolent methods Mahatma Gandhi inaugurated more than a century ago. Gandhi’s neologism for nonviolent direct action was satyagraha, which roughly translates to ‘holding fast to truth’. While this term itself never caught on, in principle or form, nonviolent models of organising protest did. For decades, pro-democracy movements in Africa, Latin America and Eastern Europe have conspicuously embraced nonviolent politics to express mass dissent and topple authoritarian governments.

Time and again, activists around the world have turned to mass boycotts, strikes and collective vigils, techniques Gandhi pioneered and practised on the world stage with historic results. More recently, protestors in the Occupy movements and the Arab Spring successfully put to use nonviolent tactics of disruption. Similarly, activists for issues including the environment, corruption, refugee and immigrant rights, racial exclusion and violence are taking up and adapting nonviolent protest to meet new challenges. This Is an Uprising (2016) by the political analysts Mark and Paul Engler promises to show how nonviolent politics can force political change on the most intractable issues of the day, from climate change to rising inequality.

Nonviolence’s evident authority, however, belies a more chequered history. Over the course of the last century, the popularity and attraction of nonviolent politics has waxed and waned. Its long-term resilience requires explanation and can provide clues to nonviolence’s purpose and power.

Plenty of activists and observers have doubted the effectiveness of nonviolent politics. Suspicions of naiveté and weakness, in particular, have shadowed the history of nonviolence from its very inception. Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr, the leading figures of nonviolent politics, both faced criticism along these lines. Skeptics viewed nonviolent methods as timid and sluggish, at best, capable of winning only small reforms. Gandhi and King’s moral commitment to nonviolence was seen to hinder the hard choices necessary for radical change.

The moral superiority of nonviolence is often evoked to condemn violent resistance and discredit unruly activists. States regularly conscript the language of nonviolence in this way, adding to worries that nonviolence carries risks of cooption and compromise. The wars and occupations of the past two decades seem unlikely portents of a new era of nonviolence. The enthrallment of force and violence seem as overwhelming as ever. And yet the encircling violence – from state violence and increasingly deadly military technology, to global terrorism and asymmetrical warfare – seems to be self-defeating at best, nihilistic at worst. That is, there is little prospect that all this violence has or will achieve its purported ends. This fact – and reckoning with it – holds out the promise of nonviolence.

For both Gandhi and King, transformative politics was a difficult road – full of disappointments and reversals. Lasting change required patience and determination, and nonviolence was the most potent and reliable means for achieving it. Far from signalling acquiescence, nonviolence was a resolutely active politics. It required the cultivation of disciplined fearlessness and moral courage to face the demands of political action.

Beginning in the late 1960s, doubts about nonviolence peaked as radical politics around the world embraced and celebrated armed struggles for national liberation, especially the anti-colonial movements in Vietnam and Algeria. Admiration for Malcolm X, Che Guevara, Frantz Fanon, Mao Tse-tung and Ho Chi Minh outweighed Gandhi and King’s authority. As the political scientist Sean Scalmer has shown in Gandhi in the West: The Mahatma and the Rise of Radical Protest (2011), protestors in the United States were also moving away from nonviolence. King’s rhetoric of love, reconciliation and interracial understanding came under suspicion, even disrepute. Dave Dellinger, a veteran anti-war activist and member of the so-called Chicago 8, argued that the ‘old’ nonviolence of Gandhi and King focused too much on moral appeals and ‘converting the enemy’. What was needed instead was a ‘new nonviolence’ that attacked systems of racial oppression and economic exploitation.

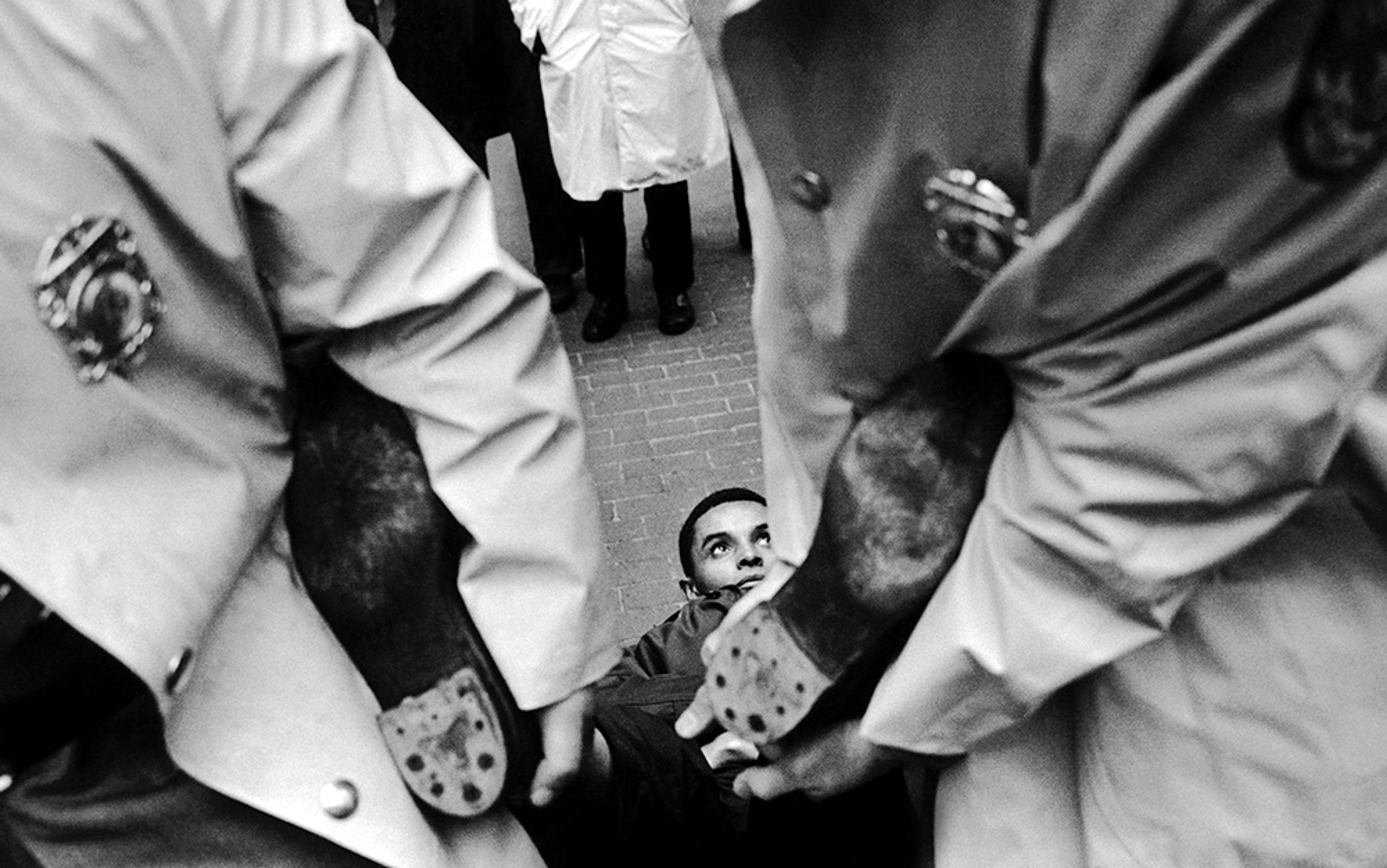

The US Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) turn away from nonviolence was equally dramatic. SNCC pioneered the lunch-counter sit-ins of the early 1960s and later the ‘jail-in’. These were two of the era’s signature techniques of nonviolent protest. The SNCC’s inaugural statement of 1960 proclaimed a commitment to the ‘philosophical or religious ideal of nonviolence’. They described it as the foundation for action that can bring about ‘the redemptive community [which] supersedes systems of gross social immorality’. But soon after, SNCC began to chafe. Under the leadership of Stokely Carmichael, in 1966 SNCC described the commitment to nonviolence as meant for ‘an audience of liberal whites’. This accommodation to a white audience, SNCC argued, came at the cost of ‘black power’. Black Power would not hold out a hand asking white liberals for charity. Black Power would instead provide the ‘community with a position of strength from which to make its voice heard’.

From streaking to the Black Panthers brandishing weapons, disruptive protest mocked authority

The change in the goals of protest, from converting the enemy to attacking the system, also signalled a change in styles of protest. Protestors opted for more openly confrontational and defiant tactics, experimenting with tactics that grabbed media attention and shocked public conscience. They sought dramatic and spectacular confrontations with the police – like the antiwar protests at the 1968 Democratic Convention – as a way to create crises and expose state violence. The Black Panthers embraced the symbolism and tactics of guerrilla war, and the Weather Underground movement followed.

The culture of protest encouraged anarchic expression and a dramatic theatre of opposition and revolt. From tactics of evading arrest and streaking to the brandishing of weapons by the Panthers, disruptive protest mocked authority and rejected prevailing social and political norms. Gone were the stoic discipline, austerity and respectability in dress and manners that characterised Gandhi and King’s protests.

In this moment of reassessment, a distinction between principled and strategic nonviolence took shape. Movements began to see nonviolence as a useful tactic rather than a defining creed. It could be adopted for pragmatic reasons but its use did not require moral conviction in nonviolence. Gene Sharp’s The Politics of Nonviolent Action (1973) exemplified this shift towards strategic nonviolence. The anti-war movement, the Black Power movement, and movements that became associated with the New Left came to see Gandhi and King’s principled nonviolence as outdated. It was, for them, ill-suited for instigating radical social and structural transformation.

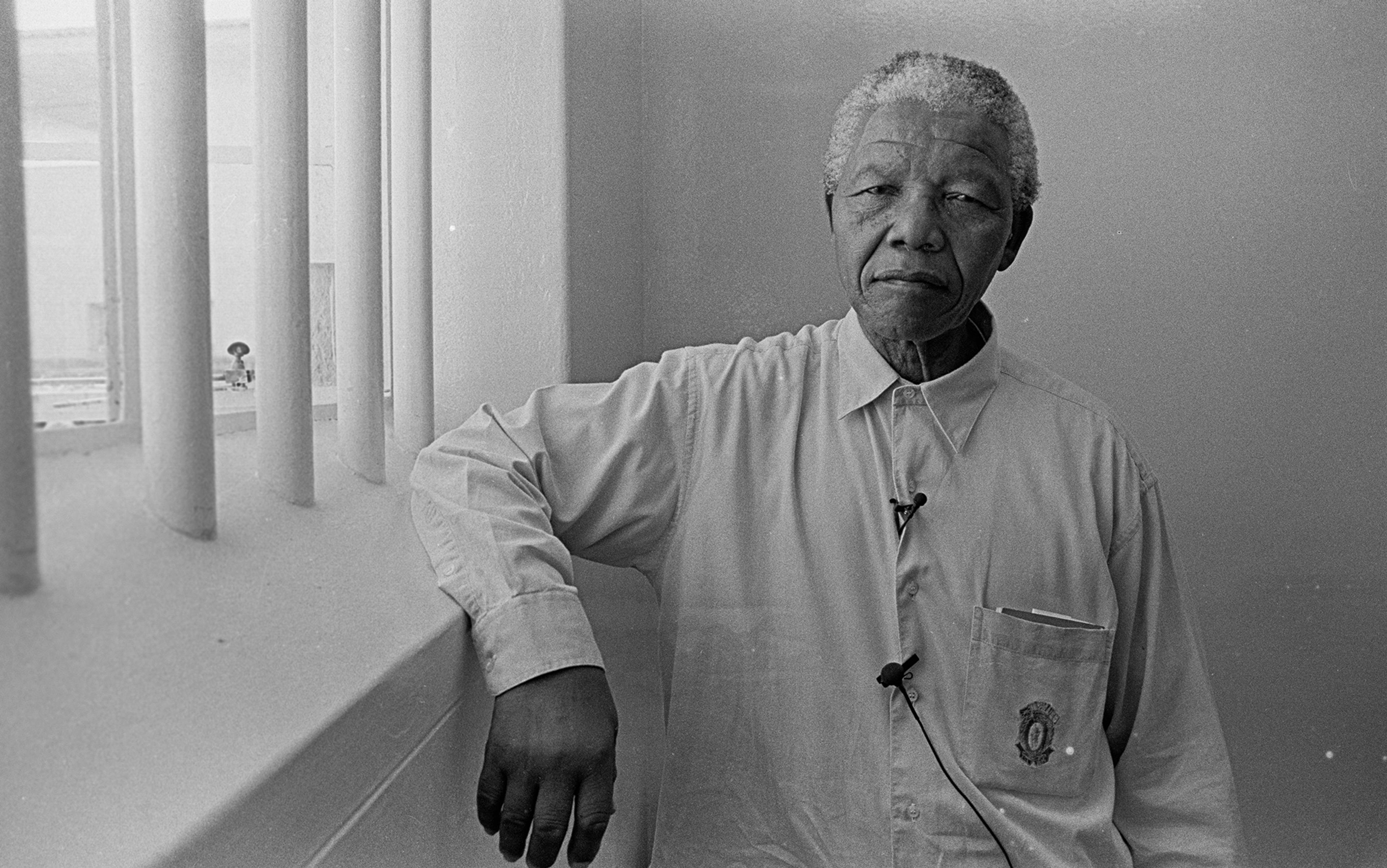

Faced with this dynamic rival, nonviolence seemed as if it might move into long-term decline. But that has not happened. Instead, in the 1980s, nonviolence reemerged in enduring ways. The ‘people power’ movement in the Philippines, the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, and the velvet revolutions of Eastern Europe made nonviolence again a central pivot of global politics. These anti-authoritarian struggles linked nonviolence to processes of democratisation. Their success infused nonviolence with a renewed vitality and legitimacy.

Why did these movements return to nonviolence as a strategy for contesting power? How did nonviolence contribute to their success? Does nonviolence effect political change by demonstrating conscientious dissent, by expressing popular power, or by moral suasion? When it comes to actual protest, what is more effective – acts of heroic self-sacrifice such as the hunger strike, or public protests involving massive crowds?

In short, what is it about nonviolence that gives it its power and accounts for its enduring appeal?

At their core, nonviolent movements eschew armed rebellion. All of these struggles achieved transformative political change without relying on either the threat of military force or any marked coordination with armed movements. Reflecting on this global revival in The Unconquerable World (2003), Jonathan Schell saw the adoption of nonviolence as more than a savvy political choice. The rise of nonviolence was tied to an equally remarkable change in the history of violence: specifically, the long-term decline of the utility of war as a political instrument. The 20th century was the era of both extreme violence and mass democratic mobilisation. Military force became unreliable as an arbiter of political conflict. In the latter half of the century, warfare and force no longer seemed capable of delivering clear-cut political winners. The momentum seemed to be swinging in the opposite direction. Political victory could be wrestled from the jaws of military defeat.

Vietnam and Algeria exemplified this reversal. The overwhelming military might of imperial powers proved futile in the face of determined, popular opposition. The application of greater force did not and could not produce submission. With the advent of nuclear weapons, the irony was complete. Military technology designed for total war had come to outstrip all political utility to the point of absurdity. To win in nuclear terms meant the annihilation of the victors and the defeated alike.

As the use of force became fraught with negative, even perverse, consequences, nonviolence became the only real option for insurgent politics. Nonviolent action is a proven way to organise and display political strength and power. Through bodies and action, it reveals where political power truly lies: namely, in the consent and assent of the people. From its very invention, nonviolence was based upon this fundamental insight – that power resides in the people. ‘In politics,’ Gandhi argued, satyagraha ‘is based on the immutable maxim, that government of the people is possible only so long as they consent either consciously or unconsciously to be governed.’ Gandhi thought that all regimes – even the most authoritarian – were based on the collaboration of the many. Mere force could never, by itself, sustain a government. The implication was clear: any regime could be disrupted by the withdrawal of that consent on a mass scale. This was the logic of non-cooperation. By diluting sources of governmental support and dramatising disaffection, non-cooperation undermines the state’s authority.

In short, nonviolent politics as practised today organises and displays collective power. In so doing, it demonstrates popular will and consent. It is seen to be the natural corollary of democracy. For the past generation, Gene Sharp has been the most well-known and effective disseminator of this view. His pamphlets outline nearly 200 techniques of nonviolent resistance and they have popped up in the hands of activists the world over, from the velvet revolutionaries of Eastern Europe to the protestors of Tahrir Square and Wall Street.

The championing of nonviolence as collective power, however, has a longer history. The Indian writer Krishnalal Shridharani’s book War Without Violence (1939) cast nonviolent action as an insurgent, countervailing form of directed mass power. It was one of the first attempts to translate Gandhian politics for the West. The US chapter of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a major international pacifist organisation, republished an abridged version that became a kind of playbook for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and SNCC. It helped to circulate Gandhian methods in the US and aided the emergence of African-American nonviolence. Shridharani, like Sharp, analogised the logic of nonviolence to that of war, as a kind of social combat.

Organised mass action creates an alternative form of power, one capable of matching forces with, and even defeating, state power. This was especially true for organisations and activists for whom nonviolence was a strategic or pragmatic imperative rather than a moral value. Strategic nonviolence employs an extensive array of tactics that generate and display power as such. Activists accept that, in order to work, these tactics might involve coercion. Nonviolent boycotts and strikes inevitably disrupt, for example, transportation networks and harm a business’s income.

But ostensibly nonviolent actions can also consciously aim to provoke the police or intimidate the opposition, for example, when crowds jeer at or physically prevent consumers from entering boycotted stores or facilities. Here ‘nonviolence’ refers to anything short of coordinated armed struggle or direct physical harm. A collective power model – tied to a theory of democratic power and legitimacy – approximates well contemporary forms of mass nonviolence such as the occupation of public squares, from Tiananmen to Tahrir. Mass gatherings display strength through the force of numbers. The larger the crowds, the better it seems to represent the popular will.

In celebrating nonviolence as a collective and democratic power, some key features of nonviolence as Gandhi and King practised it have fallen away. Gandhi and King both saw the power of suffering or discipline as essential to nonviolence. Suffering not only distinguished nonviolence from armed rebellion, it made nonviolence a unique kind of political action.

If claims to justice won easy acceptance through rational argument, there would be no need for nonviolent direct action

But as activists came to prefer strategic nonviolence, suffering lost its central place in nonviolent politics. Sharp sees suffering as part and parcel of principled nonviolence. It is the spiritual means by which nonviolence ‘converts’ the opposition, freeing both the oppressed and the oppressors from systemic injustice. Gandhi and King both held a spiritual commitment to nonviolence. Gandhi, in particular, worried that collective protest, even ostensibly nonviolent protest, can issue forms of coercion and intimidation. Suffering, however, was important politically. It has positive strategic and tactical effects in politics. It changes the tenor and dynamics of political contestation. And it has power: suffering can sway opponents and potential allies more effectively than brute force or outright confrontation. Moreover, suffering is ingrained in the form that nonviolent protest takes.

Nonviolence as collective power tries to match forces with and overwhelm opponents. Instead of intimidating or directly coercing the opposition, suffering aims to persuade and convert it. Persuasion involves its own strategic logic; it works by surprising, undermining, and outmaneuvering the enemy. Neither Gandhi nor King believed persuasion to be an easy or straightforward task. If claims to justice won easy acceptance through rational argument or explanation, there would be no need to employ nonviolent direct action.

Gandhi recognised very clearly the limits of rational debate in politics. He thought that people grew emotionally and psychologically attached to their beliefs as aspects of identity and ego. Emotional investment generates passions, resentment and indignation for example, that make rational debate and agreement very difficult. Suffering can break through to places that reason and argument cannot reach. Unlike brute force or direct confrontation that can stiffen resistance, Gandhi said that suffering works by:

converting the opponent and opening his ears, which are otherwise shut, to the voice of reason. Nobody has probably drawn up more petitions or espoused more forlorn causes than I, and I have come to this fundamental conclusion that if you want something really important to be done, you must not merely satisfy the reason, you must move the heart also. The appeal of reason is more to the head, but the penetration of the heart comes from suffering. It opens up the inner understanding in man.

Suffering can weaken entrenched positions. It, unusually, can reach the heart of the opponent in ways that might lead to the rethinking of commitments.

Suffering often conjures up images of moving and exceptional feats of self-sacrifice, for example the Gandhian hunger-strike or the US Civil Rights activists enduring beatings. But suffering in Gandhi’s conception of it was less concerned with physical distress per se and something more along the lines of self-discipline in action. Indeed, ‘self-suffering’ was Gandhi’s translation of the Sanskrit term tapas or tapasya, which more readily signals practices of ascetic self-mastery.

Gandhi’s Salt March (or Salt Satyagraha) of 1930 and King’s 1963 Birmingham campaign are two of the most celebrated events in the history of nonviolence. Both campaigns used the power of suffering to dramatic effect. Nonviolent protestors were subjected to brutal police responses. Iconic images and accounts of the violence circulated throughout the world. Suffering exposed the violence of the state and shifted public opinion against it. Though usually unstated, this kind of confrontation, and the sympathy it produces, is often the goal of nonviolent protest politics.

nonviolent protests, like all protests, involve coercion, intimidation and disruption

What mattered most for Gandhi and King was less the suffering inflicted than the discipline protestors displayed in the face of provocation and assault. The ability to dramatise and display tapasya was paramount to the success of nonviolent protest. Discipline mattered both in the organisation of the protest and in the comportment – and constraint – of the protestors.

The need for discipline imposed a strict form and code on nonviolent action. Gandhi and King formulated a plethora of rules for nonviolent activists. They circulated rules for how to dress, how to walk, and how to talk during nonviolent marches, strikes, pickets and boycotts. In both the Salt March and the Birmingham campaign, for example, protestors had to explicitly assent to these rules in the form of a vow or pledge in order to participate. Allegiance to these rules showed that activists were willing to bear the costs and burdens of protest themselves, from the costs of self-organisation to willingly accepting punishment for breaking the law. Most importantly, the rules were meant to help muster and exhibit stoic discipline in the face of threats, intimidation and outright violence.

How does this tapasya work to persuade recalcitrant opponents? How can it, in Gandhi’s words, ‘open an opponent’s ears’ or ‘pierce their hearts’? The theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, another important early interpreter of Gandhi, offered one of the most insightful accounts of the positive political effects of nonviolent suffering. Like Shridharani, Niebuhr also had an influence on the Civil Rights movement. King’s understanding of nonviolence drew upon Niebuhr’s appraisal of Gandhi in his seminal early work, Moral Man and Immoral Society (1932). What made Niebuhr such a canny analyst of nonviolence was that he, like Gandhi, saw politics to be riven by irrational sentiments, drives and passions.

Niebuhr was a political realist, perhaps the most influential realist of the 20th century. As such, he argued that political conflict was rooted in struggles of and over power. At the same time, political contestation generates and is exacerbated by resentments and egoistic sentiments. People take criticism of their political beliefs and position very personally, as insults and unjust accusations. Movements that question privilege will be met by indignation, animosity and resistance. Moreover, insurgent movements, movements that question the status quo, suffer a triple burden. They have to fight a better-resourced and entrenched opposition. They face the impassioned hostility that the contestation of privilege provokes. Protestors are readily branded as criminals, anarchists and inciters of violence.

Disciplined nonviolence can disrupt these natural presumptions and dynamics. Niebuhr saw that nonviolent protests, like all protests, involve coercion, intimidation and disruption. Protest in the form of economic boycott or a nonviolent march or demonstration will understandably be resented by those against whom it is aimed. But more neutral bystanders whom the protest incidentally disturbs and inconveniences might also respond with hostility and misunderstanding. The Occupy movements, for example, generated criticism as public nuisances.

Gandhi and King saw that it would not be morally and politically wise to make resentment the face of political action

Successful movements try to mitigate these negative consequences through the style and structure of nonviolent protest enacted. By ‘enduring more suffering than it causes’ (in Niebuhr’s words) nonviolence demonstrates goodwill towards the opposition. Its discipline displays a moral purpose beyond resentment and selfish ambition. Together, goodwill and the repression of personal resentment temper the passionate resistance of opponents. Ideally, this tempering can help to weaken the opposition’s entrenched commitments. More often, it has a salutary effect on potential allies of the movement, the neutral observers and the public at large. When protestors adopt discipline in their comportment and dress, this negates portrayals of them as criminal elements or enemies of public order. The jeering opposition is now exposed as irrational and uncivil in their response to the civility of the protestors. Disciplined, temperate protestors can divert and reduce hostilities to help the public to see beyond the inflamed situation to the underlying dispute.

Gandhi and King’s nonviolence required the repression of resentment and anger to garner the right political effect. Neither of them denied anger was a justified response to the experience of oppression, but they saw that it would not be, in Niebuhr’s terms, ‘morally and politically wise’ to make resentment the face of political action. Resentment, anger and indignation arouse opponents’ egoism and hostility, and tend to alienate bystanders. This was why, for Niebuhr, ‘the more the egoistic element can be purged from resentment, the purer a vehicle of justice it becomes’.

The history of nonviolent politics has revealed and confirmed the transformative power of coordinated mass action. It has also shown that force alone can neither induce popular consent nor reliably secure political victory. In line with these findings, the political scientists Maria Stephan and Erica Chenoweth in their award-winning book Why Civil Resistance Works (2011) show nonviolent collective action to be especially effective against authoritarian governments, overturning a longstanding assumption that nonviolence can be viable only in and against liberal regimes.

These findings might also point to qualifications of nonviolence as collective power. While such protest can topple governments, it is less clear how it can sustain a new democracy. The superiority of numbers that so potently expressed mass dissent risks turning into majoritarian displays of power. Ironically, nonviolent politics can actually face more hurdles in democracies. Authoritarian legitimacy has proved to be a brittle façade, easily exposed as such by nonviolent tactics of disruption and provocation. Democratic publics, however, are surprisingly hostile to these same kinds of tactics. Democracy by definition provides institutional channels to express dissent and effect political change. When these channels and institutions are seen to be legitimate, insurgent politics are readily branded as extreme and tend to elicit polarising and passionate responses.

Nonviolent discipline might have a constructive role to play in both situations. Disciplined action and its orientation towards persuasion can help to mitigate the coercive effects of, and negative responses to, insurgent collective protest. Democratic politics are driven by the dynamics of passion and power. The open and continual contestation for power fuels resentments, antagonism and polarisation. Nonviolent suffering offers subtle and proven ways to overcome these tendencies and navigate the hard but necessary road of political persuasion. Retrieving this lost element at the core of 20th-century nonviolence is key to sustaining and shaping nonviolent politics for the 21st century.