Willy hated dirty things. Dusty cans of Coke in small shops, stained tables at noodle diners: they reminded him of the small-town poverty of Anhui, his home province, where he’d started work at 13 and earned his way to university before moving to Beijing. Willy would refuse to eat in a restaurant if he found a mark on a glass.

At 23, he was trying hard to shake off country habits, like his accent. But some stuck like burrs until others dislodged them. ‘Mia!’ he said. ‘You know, when I first saw her, I thought she was a monster. I was scared of her. I didn’t want to go near her because I thought she would curse me.’ His face flushed with embarrassment, then broke into a smile: ‘But now I think she is the most beautiful of all the girls.’

Willy and I had worked together at a summer programme in Beijing in 2004, teaching the winners of a Henanese English competition, including Mia. They were sweet but conventional provincial teenagers, excited to be in the capital. But Mia, though already 20, still lived in the Luoyang Children’s Home, where she had been raised since being abandoned shortly after birth by her parents. Born with scoliosis, she stood around 4ft 6in, her back crooked and walking with the aid of crutches. It was common practice to call nameless girls Dang (‘party’) and boys Guo (‘state’), and so her name was Dang Miaomiao, ‘little darling of the party’.

Mia was smart, dry, and curious. Sometimes mistaken for a child, she wore small, stylish earrings and a sharp haircut to mark herself out as an adult. When we climbed the steep stairs at the Forbidden City together, she refused my arm. She’d won several provincial competitions in both English and art. The children’s home was the only family she knew, but they had good staff and foreign volunteers, including skilled medical personnel; when I saw her again in 2005, we went for dinner with staff from the orphanage, whose love and respect for her was obvious.

Mia could win over anybody who knew her. But to get those chances meant battling past a wall of entrenched prejudice and fear. Willy had been able to get past his initial feelings about her, motivated largely by his desire to ‘not be a peasant’, but others were complacent in their bigotry. Despite her intelligence, she had not received any university offers, and her chances of employment were worryingly slight. Chinese universities routinely reject qualified candidates with the excuse that their ‘physical condition does not meet the needs of study’ – a policy of discrimination written into some schools’ constitutions. Meanwhile, figures published in Chinese state media last year show that only a quarter of disabled people are able to find any form of employment.

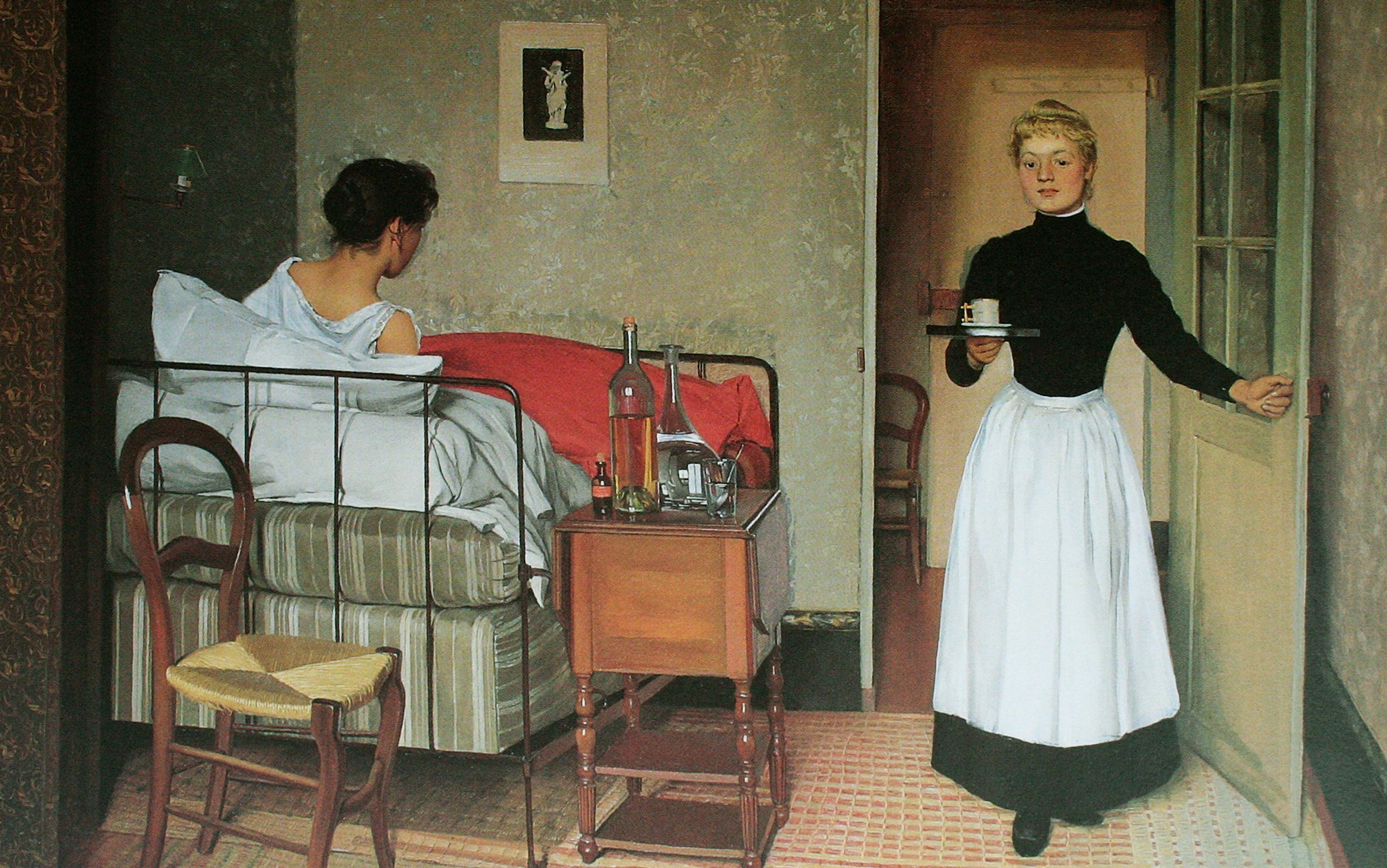

Miaomiao Dang. Photo supplied by the author

If you judged the country by its laws alone, China would be a global leader on disability rights. The ‘Laws on the Protection of Persons with Disabilities’, introduced in 1990, offer strong and wide-ranging protection of the civil rights of the disabled, guaranteeing employment, education, welfare, and access. But despite the high concerns of the law, Chinese cities make little concession to disabled people. As the sociologist Yu Jianrong has documented, raised pathways for the blind often lead into dead ends, bollards, trees or open pits, or else spiral decoratively but misleadingly. Wheelchair access is non-existent, especially outside Beijing or Shanghai, and guide dogs are effectively forbidden from most public spaces, despite the authorities’ repeated promises of full access.

‘We never leave the facility,’ Yang Wenzhi, 55, told me in 2011. We sat in a concrete pavilion just outside the hospital in Tangshan, together with two others left unable to walk by the earthquake of 1976. The heavy wheels of Yang Wenzhi’s chair crunched autumn leaves as he gestured at the grey buildings of the hospital where he had spent decades. ‘Where could we go? Nowhere in town is reachable by wheelchair. And all our welfare money is taken by the doctors anyway.’

The Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games saw a spate of Potemkinisation. ‘We never allow guide dogs on board, except [that we did] during the 2008 Olympic Games,’ a bus driver told the Global Times in 2012. Ramps were hastily installed at hotels and stadiums. A well-intentioned manual reminded volunteers not to stare, and that physically handicapped people were ‘often mentally healthy’. Meanwhile, beggars, including the disabled, were cleared out of the streets for the duration, by police unwilling to let the capital’s face be blemished.

Ambitious government pledges go unfulfilled across the country. The law says that children with special needs are entitled to proper schooling, but there are no provisions for funding. Local authorities regularly turn away children, telling them to go to ‘special facilities’ elsewhere that don’t exist, or that are far out of their parents’ financial or geographical reach. As a result, according to a 2013 report by Human Rights Watch, 43 per cent of disabled Chinese people are illiterate, compared with 5 per cent of the general population. Only a third receive the services they need, according to Handicap International, and only a fifth get assistive devices, such as walkers, prosthetics, or adapted software. And, since welfare funds are often stolen, delivered late, or impossible to access – thanks to the Byzantine turns of the country’s regulation system, which limits aid to the recipient’s province or even village of birth – only around 15 per cent receive any funding.

shut away from sight or sound, trapped in fear, malnutrition and neglect, these children are left moaning like animals

In the countryside, disabled children fare far worse. Often, they are confined within the house and kept away from outside eyes. Employees of NGOs tell horror stories of what they’ve seen: shut away from sight or sound, trapped in fear, malnutrition and neglect, these children are left moaning like animals. Sometimes they are chained to prevent escape, or to ease the pressure on parents or grandparents already struggling under poverty and shame.

As I write this at 3am, I can hear the grind of an earthmover outside laying the foundations of another mall in central Beijing. I think of the utopia that Ursula K Le Guin created in the short story ‘The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas’ (1973): ‘The child, who has not always lived in the tool room, and can remember sunlight and its mother’s voice, sometimes speaks. “I will be good,” it says. “Please let me out. I will be good!”’

Every so often, pictures of children chained up like dogs surface online – such as the photos of the 11-year-old boy He Zili last November – prompting a brief-lived spasm of anger and pity. Most commonly, these children are confined by parents who simply have no choice; without community or government aid, and with child kidnappings and abuse common, parents lock away children simply to protect them. China does have child welfare laws, but they are rarely enforced because there is no professional or financial interest for ‘social workers’ or police to do so: there is no monthly tally of children to rescue, unlike existing quotas of foetuses to abort, prostitutes to arrest, or petitioners to block from reaching the capital. Disabled children fall victim to the country’s faltering orphanage system: John Giszczak, a former China programmes manager for Save the Children says ‘95 per cent of Chinese orphans have special needs’.

Like European child welfare before the 1980s, the Chinese system is riddled with sexual and physical abuse. The British documentary The Dying Rooms (1995) showed horrific mistreatment of disabled children; the Chinese government’s reaction was not to change the system, but to issue a series of crackdowns to keep foreign media out of institutions, and to accuse the reporters of stripping the children naked and tying them up themselves.

Yet it is not only disabled children who are abused. Disabled adults are sometimes kidnapped or enslaved, as in a notorious series of cases in 2008-9 when dozens of people were rescued from forced labour in brick kilns in west China. Some had been taken in by organisations purporting to care for the mentally handicapped, and then sold hundreds of miles away.

In part, the gulf between law and practice stems from the institutional problems that plague every aspect of government in China. Originally, the People’s Republic of China barely took an interest in the disabled, save through a few isolated organisations dealing with specific conditions such as blindness. The China Disabled Persons’ Federation (CDPF) – today a quasi-governmental organisation – started in 1988 as an activist movement driven by disabled people themselves. Many of them had been crippled during the Cultural Revolution, most notably the group’s chairman, Deng Pufang, son of the country’s then leader Deng Xiaoping, and a paraplegic since 1968, when he jumped out of a window to escape torture by the Red Guards.

The CDPF was a fierce and determined group, and one with political muscle; nobody could ignore an organisation led by the child of the ‘paramount leader’. The progressive laws of the 1990s are largely a result of pressure from the CDPF, as was the abandonment of the previously common term canfei (‘handicapped and useless’), in favour of canjiren (‘disabled people’). Yet as the CDPF became institutionalised, it stopped being an activist movement, and became a government bureaucracy that wields massive power in the lives of disabled people but has little sway within the government hierarchy. Today it’s tasked, simultaneously, with advocating for people with disabilities and being a provider of government aid to them.

The percentage of disabled people inside the CDPF dropped sharply after the 1990s, and positions started to be handed out as nepotistic sinecures. For most CDPF officials, their job is a simple posting in a bureaucratic career, not an advocacy role. ‘I am the only person in my office with a disability,’ a deaf official in a Hunan branch of the CDPF told a journalist colleague, asking for anonymity. ‘Most of my colleagues don’t take our work seriously. They just think disabled people are always asking for money.’

But even when the CDPF has been able to act, corruption, prejudice, and poor administration have limited its value. National regulations mandate that 1.5 per cent of employees at larger businesses must be disabled, or else the enterprise faces a fine. Collecting these fines was left up to the CDPF, which seldom had sufficient clout to get the money. In 2008, however, the tax authorities were made responsible for collecting the fine, and revenues jumped significantly. They passed the funds back to the CDPF, which suddenly found itself flush with cash. Yet distressingly little of this money has made its way to people with disabilities. Instead, it was squandered, as John Giszczak outlined for me, on ‘a whole bunch of firms [which had sprung up] selling pseudoscientific “therapeutic” equipment to the CDPF at overinflated prices. Now CDPF centres have warehouses full of it, brought for millions of yuan and entirely useless.’

Beijing’s signature of the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2008 has given disabled advocates leverage to use against recalcitrant local authorities. Empowered by this, disabled people are taking activism back into their own hands, forming advocacy groups away from the CDPF umbrella. But institutional failure is normal in China, especially in social welfare and health care, the two areas with most impact on people with disabilities.

Underneath these institutional factors, and just as important, are layers of cultural prejudice. Take the now strongly enforced requirement to employ disabled people. More than 90 per cent of businesses, according to the CDPF, have preferred to take the substantial financial hit rather than comply with the mandate. (Compliance with similar laws in other East Asian countries runs at about 25 per cent.) A survey by the Beijing Yirenping Center, a local disability rights NGO, found that even government departments have, at the very best, 0.39 per cent disabled employees.

‘People are uncomfortable with the disabled. If they saw we had disabled waitresses, they wouldn’t come’

A range of excuses are offered up for non-compliance, often disguising prejudice as practicality. ‘I don’t have a problem with them, but people are uncomfortable with the disabled. If they saw we had disabled waitresses, they wouldn’t come. Besides, our restaurant has many stairs. It would be too hard for them,’ the manager of a popular eatery in Tangshan told me. Studies of Chinese college students, and Americans from Chinese families, show strong implicit biases against the disabled, especially those with mental disabilities.

Such feelings are not unique to China. Every society has long-standing prejudices against the disabled. Until the rise of sentimentality in the 19th century, mocking imitation of the elderly, the lame, the blind or the mad was common practice in Europe. In Georgian England, leading a blind man into a ditch or kicking the crutch from a cripple was considered an excellent joke. Even in the early 1980s, ‘spastic’ was a casual insult on my English primary school’s playground.

The continuing popular horror of disability today points to the strong grip of Chinese traditions that conflate biology and morality. One of the most powerful of these is the patriarchal Confucian notion of the importance of lineage. Confucianism sees the body, especially if male, as part of a chain of continuity stretching back to an individual’s ancestors and forward to his descendants. In this vision, a crippled or deformed body is a perversion – one often attributed to the moral or spiritual flaws of parents, especially mothers, who are blamed for their failure to follow medical superstitions, such as post-natal confinement or the avoidance of certain foods during pregnancy.

As a result, birth defects occasion far more fear and disgust in China than disability caused by accidents. ‘Sometimes people outside the city think I was born like this,’ commented one travelling businessman, showing me the prosthesis he’s worn since he lost a leg in the Tangshan quake in 1976. ‘And I tell them quickly, “no, no, it was the quake.”’

to have a disabled child was to fail not only your family, but your country and your people

In the early 20th century, the Confucian-influenced attitude took a darker turn. As the Dutch historian Frank Dikötter traces in his book Imperfect Conceptions (1998), with the influence of Western eugenics and fears of failing national strength, the individual body became associated with the national body: to have a disabled child was to fail not only your family, but your country and your people.

Communism had its own obsessive interests in the powerful body and the strong state. The People’s Republic inherited its notions of disability from the Soviet Union, where disability, like all forms of inequality and suffering, was supposed to be washed away by socialism. Questioned in 1980 by a British journalist about whether Moscow would participate in the Paralympics, one Soviet official barked: ‘There are no invalids in the USSR!’ In the Maoist years, disabled people could be held up as model workers if they exceeded their own physical limitations to ‘contribute to the country’, but the examples chosen were almost always those disabled by accident, not birth, such as the writer Zhang Haidi, paraplegic since an operation was botched when she was five.

The concern with national strength is evident in China’s 1995 Maternal and Infant Health Law (originally, and bluntly, called the ‘Eugenics Law’) which instituted checks on the health of potential parents before marriage, encouraged the abortion of ‘defective children’, detected in the womb, and the supposedly voluntary sterilisation of the disabled. While the law promised to respect ‘consent’, in practice, unsurprisingly, it rarely lived up to this.

For parents of disabled children, it was another dose of shame and oppression. But this is one of those areas in which the state’s failure to enforce its own laws has been a blessing; as sinister as the law reads, the medical and family planning authorities responsible for enforcing it always concentrated more on the number of children, following the One-Child Policy, than their supposed quality. Thankfully, the law’s provisions were effectively abolished between 2001-2004, as part of an across-the-board spate of legal housecleaning.

A hearty dose of prejudice also comes from Chinese Buddhist traditions, such as the belief that disability is a punishment for sins in a previous life. Beth-Ann Bloom, a genetic counsellor who works with Asian immigrant communities in Minnesota, described her experiences working with parents from Buddhist backgrounds who ‘often believe that a severely disabled child must have been a rapist, thief or murderer. The first thing I tell them is: “This child will not be violent. This child will never hurt anyone.’’’

‘Don’t give them anything! They’re like this because they were wicked in their last life’

A friend spoke of being taken, in 1997, when she was in middle school, to visit smaller children in an orphanage in Changsha. She and her classmates were moved by the children’s destitution and wanted to give them candy and money, but they were told by the staff: ‘Don’t give them anything! They’re like this because they were wicked in their last life.’

Mainstream Chinese Buddhism also makes an association between physical appearance and moral virtue, particularly manifested in its religious art. There are long lists detailing how a Buddha should be depicted. His ankles are rounded and undented, his feet are of equal length, his knees do not protrude, he is right-footed, his navel is without blemish, his toes well-proportioned, he has lovely teeth, and his penis does not dangle. The physical perfection of a Buddha’s body reflects his equally superb spirit.

The disabled, whether working off their karmic burden, or disturbing the order of things by their presence, bring ill fortune with them. Laughing at his own fears about Mia, Willy told me: ‘In my hometown, we believed that to touch a disabled person brings bad luck, especially if you are pregnant, because your child can be born with the same problem.’ This echoes a long-standing belief that the broken image of the disabled might impress itself onto the foetus in a form of spiritual contagion.

Sometimes, the disability is attributed not to past sin, but to current malevolence. ‘I know one very wealthy family,’ Ting-I Tsai, a Taiwanese journalist, told me, ‘who were having a son, but the sonogram showed severe problems. Most Chinese would abort in that case. But they thought that somebody jealous of their fortune or a business rival must have put a curse on them. If they didn’t draw off the curse by having the baby, it would strike or hurt them elsewhere. So they had the child to act as a supernatural lightning rod.’

China’s prejudices often inspire dreams of salvation among Westerners. It seemed like a kind of miracle to me when Mia was sponsored by an evangelical American couple to live and study in the US in 2006, not least because it resonated with my family’s own experience. My grandparents, a vicarage family, adopted my aunt from a Hong Kong children’s home in 1971, choosing her in part because she had a cleft palate and was unlikely to find a foster family there. They had never seen her, and for a year and a half my grandfather’s only contact with his adopted daughter came through letters; when she landed in the UK, he ran to sweep her up into his arms, booming out John 1:14, ‘And the word was become flesh, and dwelt among us …’

There is a long link between Christianity and disabled care in China. The first modern disability organisations, established in the 1920s and focused around blindness, grew out of medical missionary care. Evangelical Christians are prominent as both clients and staff of adoption agencies, many of which are explicitly religious; and among disability NGOs and care groups, a disproportionate number of the staff and workers, in my experience, are local Christians.

For those with disabilities, a belief system centred around a beaten and broken body can have particular meaning. For Mia, the image of God as Father is both an obstacle and an inspiration. ‘I know all the good characters of the father God,’ she posted reflectively on Facebook, ‘but I struggle with what a father’s love looks like in reality. [Being] without a birth father does not change the way God loves for me. In fact, not having a father allows me to lean on God more closely.’

Disabled people, especially orphans, are marginal enough to be left to the Christians

Christian work with the disabled prompts less nervousness from the Chinese authorities than other religious outreach efforts in the country, which raise fears of cultural colonialism and social instability. Disabled people, especially orphans, are marginal enough to be left to the Christians. But any meaningful cultural shift in Chinese attitudes is unlikely to come from Christianity or the West, which have their own share of historical, theological, and ideological problems with disability.

But there’s another Chinese tradition, as old as Confucianism, that laughs at the idea that productivity is the measure of life, or the body the measure of virtue. For Daoists, everything, and every life, has its own Dao – its own way, not measurable by set notions of usefulness.

Sam Crane, an American professor of Chinese politics and philosophy, has been one of the most compelling writers on Daoism and disability. Daoism was his key to understanding his own son’s profound disability. In his book Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Dao (2013), Crane writes: ‘I found myself drawn back to the [chief Daoist texts] Daodejing and Zhuangzi … and found some comfort there […] I came to see that Aidan’s life, precisely as it was unto itself, was as valuable as any other.’

The happiest person I ever met in China, maybe anywhere, was Little Ma, reading fortunes from her wheelchair in a Tangshan park; joy bubbled out of her like a spring. My assistant and I came away grinning like fools at each other, for no reason other than her infectious delight in the world. She had been a dancer but, after the earthquake crippled her as a teenager, she had wanted nothing more than to die. ‘But I learnt to accept that it was how it was,’ she said. ‘And I had many people who loved me. So now I’m happy, and I use these [Daoist fortune-telling books] to tell other people what will make them happy.’ She giggled conspiratorially. ‘It’s 70 per cent psychology!’

The Daoist approach is not abstractedly philosophical. In the Zhuangzi, disability is riotously celebrated. A parade of grotesques enjoy heroic roles. Old men rejoice in their own gnarly bodies. ‘If my arm is transformed into the shape of a crossbow,’ one reflects happily, ‘I’ll shoot down an owl and roast it for dinner! If my buttocks change into wheels, I’ll never need a chariot again!’

One man is ‘the ugliest you’ve ever seen’ but every man wants to follow him and every woman to be his concubine. In one of the parables, ‘Crippled Shu’ has a body all mixed up, from his chin in his belly button to his thighs jammed up next to his ribs. But he makes enough to feed himself and others, he lives out his days, and when the authorities come to conscript soldiers, or to press people into forced labour, he waves goodbye to his unfortunate able-bodied fellows. ‘How much better than if his virtue was crippled!’

Lame, eccentric, transgendered, ugly: the Eight Immortals are among the most popular of gods

This delight in physical and mental variance extends into religious Daoism. In contrast to the dull sameness of ascended Buddhists, the Daoist pantheon is diverse and messy, like the infinite variety of Catholic saints. Take the Eight Immortals, once ordinary men and women. Their leader, Lu Dongbin, is handsome, but gets drunk and loves the ladies. Next to him is Iron-Crutch Li, old, ugly, and dirty, leaning on his crutch and carrying his medicine gourd. Zhang Guo Lao, half-mad, rides on his donkey backward. Lan Caihe is a man, or a woman, or both; it’s not exactly certain. Lame, eccentric, transgendered, ugly: they are among the most popular of gods.

The eclectic and empowering community of Daoism resonates with the thrust of global disability advocacy today. Alessandra Aresu, communications director at Handicap International in Beijing, explained the direction their work is taking. ‘Chinese approaches to disability have followed the charity model in which people with disabilities are seen as passive recipients of care and support,’ she told me. ‘We emphasise a different approach that focuses on inclusion and equal participation.’

Shifting attitudes won’t magically fix institutional failings; even Mia’s loving, communal home in China couldn’t provide her with a meaningful job, or a way to support herself independently. She found those in the US, where she now lives with room-mates and works in childcare development in Seattle. But breaking down prejudices and building up a vision of inclusive disability rooted in Daoist and other philosophies allows us to see how a Chinese system could work. I find myself turning again to the Zhuangzi, a book simultaneously mystical and practical:

Hence, the blade of grass and the pillar, the leper and the ravishing beauty, the noble, the snivelling, the disingenuous, the strange – in Tao they all move as one and the same. In difference is the whole; in wholeness is the broken. Once they are neither whole nor broken, all things move freely as one and the same again.