Tibetan Buddhism, in the pop-cultural psyche of the United States, is the Dalai Lama’s face, grinning from a cover in the self-help section of your nearest bookstore. It’s a monk in a maroon robe sitting calmly in a full-skull electrode cap as researchers probe his mind to learn how meditation plays into his unique serenity. It’s that over-the-top scene from the film Seven Years in Tibet (1997) in which Brad Pitt is trying to build a movie theatre for the young Dalai Lama in Lhasa in the 1940s when he realises that his local crew has such a strong reverence for life and abiding patience that, to a man, none is willing to harm worms while digging ditches.

Which is to say, Tibetan Buddhism in the US pop-cultural psyche is a monolithic and benign spiritual tradition built around simple wisdom, loving calmness and unflinching non-violence. This belief in an uncomplicated, compassionate and progressive Tibetan Buddhism is what allows us to reliably portray Tibetan Buddhists as sympathetic victims in the media. It’s what powers headlines in The Onion such as ‘Buddhist Extremist Cell Vows to Unleash Tranquility on the West’ – and what at one point created an unprecedented market for Tibetan nannies in cities such as New York. However pervasive the stereotype, though, the US vision of Tibetan Buddhism is anaemic, to say the least.

Sure, compassion is central to the faith. But there’s room for violence as well. Medieval Tibetan tales describe religious teachers breaking students’ bones, then healing them magically to bring them insight; they tell of monks assassinating corrupt kings to save Buddhism in Tibet. Modern history brings us the stories, often neglected in the West, of the CIA-backed violent insurgency that Tibetan Buddhists waged against the Chinese occupation from the 1950s to the mid-1970s – and of an all-Tibetan refugee unit formed in India to fight the Chinese in a 1962 war.

Far from being easy to grasp and anodyne, Tibetan Buddhism is rich in tantric practices, the impenetrably esoteric ideas and techniques used to try to slingshot spiritual seekers directly towards the enlightenment they seek to attain within this lifetime to best help others. It is difficult to succinctly sum up the diverse tantric traditions and sub-traditions, each of which contains a trove of doctrines and practices, some of which monks intentionally obscure from lay audiences, for fear that they will be misused or misunderstood by non-initiates.

Perhaps the best-known esoteric tradition in the West is the Kalachakra Initiation, the ceremony in which the Dalai Lama or other high-ranking monks slowly construct beautifully intricate mandalas out of coloured sand, and then wipe them away. Laypeople in the West usually read this ritual as simple religious art married to a lesson on the impermanence of everything. But building the mandala is part of a larger ritual process meant to prepare young acolytes for spiritual transformation. To drastically over-summarise, the mandala becomes a representation of, and portal into, the abode and mind of an enlightened deity, which monks can mentally travel through, psychically mainlining the whole of Buddhist thought from an elevated perspective. The mandala is seen as so magically charged that its dissipation actually spreads spiritual benefit into the wider world. Many tantric practices are similarly opaque and magical to outsiders, yet, because they deal with compassion and meditation, remain somewhat comprehensible to the pop-Western mind.

But other tantric traditions harness toxic emotions such as hatred, pride or desire to fuel the spiritual quest. Take for example karmamudra tantric practices, in which a spiritual practitioner, sometimes a monk and sometimes not, uses sexual intercourse to speed towards enlightenment. The sex is ritualistically controlled, and meant to help one inhabit the mind of enlightened beings. But the details of how that works are incredibly unclear to anyone outside of the tradition, and there is active debate within Tibetan Buddhist circles about how, when or even if it should be practised, much less described to laypeople. It is easy to see how these traditions could be warped, after all – how someone could spin a sex-as-spiritual practice into a form of coercion, dressing up carnal desires in sanctified garb, and foisting them on otherwise unwilling partners.

This diversity of practices and perceptions of them speaks to the fact that, contrary to popular Western perceptions, Tibetan Buddhism is hardly monolithic. The Dalai Lama is not the pope of all Tibetan Buddhism, as many seem to believe, but the head of one of four major schools, the Gelugpa. The current Dalai Lama just happens to be a particularly famous frontman whose charisma has united diverse Tibetan Buddhists into one movement. Today, he preaches cooperation between different forms of Tibetan Buddhism, but until the 1970s he embraced the veneration of an exclusively Gelug protector spirit – one that punished anyone who polluted the school with teachings from other traditions.

It’s understandable that Americans wouldn’t know every nuance of Tibetan religious traditions. After all, it takes most monks a lifetime of rigorous education and practice to grasp even a few corners of it all. But the gap between our rosy, flat picture of Tibetan Buddhism and its reality is vast. It is not inexplicable, though. It is the result of the headspace that Americans were in when they first encountered Tibetan Buddhism, and the way in which, in turn, that Tibetans reacted to the American gaze.

Buddhism found a beachhead in the US during the first half of the 19th century, when Chinese immigrants arrived on the West Coast. These communities remained fairly isolated in a nation that largely saw them as racially inferior; their strange faith of ritualistic offerings and chanting was just one more bizarre, damning thing about them. When Americans and other Westerners did engage with Buddhism around this period, usually as Christian missionaries in Asia, they tended to walk away with a grim picture. They interpreted its doctrines of emptiness and non-attachment as life-denying nihilism. These terms actually refer to the idea that nothing has firm or inherent meaning. Instead, everything is interdependent and in constant flux. So rather than latching on to fixed views of our worlds, and by doing so courting suffering, we ought to embrace the flux. Western observers often warped this into the notion that nothing means anything, and that we should be indifferent to everything. Buddhists still have to push back on this misperception to this day.

That changed in the latter half of the 19th century, as Western scholars studying newly accessible texts from India, where Buddhism was no longer a truly lived tradition, engaged the faith through old philosophical tracts, and cherrypicked parallels between it and their intellectual hobbyhorses.

‘These texts often are not reliable guides to understanding actual living Buddhists,’ said Donald S Lopez Jr, a Buddhism scholar at the University of Michigan, who has written extensively on this history. Just like a random selection of Bible passages would not be a reliable guide to understanding Christianity as it’s lived, interpreted and practised across the world in the modern era.

Western intellectuals nonetheless proceeded to pump out a stream of highly problematic publications on Buddhism. The British orientalist Sir Edwin Arnold wrote The Light of Asia (1879), an original poem telling the life of the Buddha. But in writing the poem, Arnold reportedly drew piecemeal on scattershot sources, mixing up stories from different Buddhist traditions or exercising poetic licence to draw parallels between the Buddha and Jesus Christ, and between Buddhism and his own Christian-based spirituality and interests in rigorous scientific inquiry. The result, a biography filtered through Arnold’s values, still read well; at once familiar and enticingly novel to peers in his homeland, it became one of the first widely read English-language books about Buddhism.

Henry Steel Olcott, an early US theosophist who’d gone to India and Sri Lanka searching for proof of the power of auras, hypnotism and other occultic spiritualism in vogue in the era, found ancient Buddhist texts and wrote The Buddhist Catechism (1881). In it, he painted Buddhism as thoroughly modern, a rationalist endeavour fusing the spiritual with the scientific. He rejected as worthless the ritual, dogma and monastic hierarchy actually intrinsic to living Buddhism. Olcott held that these aspects of the faith were cultural barnacles, born out of generations of misunderstanding and distortion of true, original Buddhism – never acknowledging that he might be the one misunderstanding the faith.

Paul Carus, a German immigrant to the US, cobbled together existing translations of Buddhist texts into The Gospel of Buddha (1894), which he presented as a cohesive and faithful rendering of Buddhist philosophy. However, he too was mostly interested in using Buddhism to advance a vision of scientific spirituality. He had a nasty habit of deleting text that didn’t accord with that vision, while writing entirely new chapters based on his interpretations of one or two lines in Buddhist documents, all while conveniently neglecting to point out his omissions or additions to readers.

Buddhist-based mindfulness practices are used to teach dissatisfied cogs in corporate systems to suck it up

These authors and others like them fundamentally changed the way that their contemporaries viewed Buddhism, pushing back on the idea that it was a bizarre mystic cult or a nihilistic shrug of a faith. They also laid the groundwork for the way most of us think about it today: as a philosophy and way of life, grounded in rationalist enquiry and compassion, spiced with meditation, and open equally to all. Never mind the garnish of karma, nirvana or rebirth, nor any of the complex cosmologies, rituals or monastic orders and hierarchies of power based on official religious attainment found in traditional societies. In stripping away those elements of the faith, early Western Buddhist advocates separated Buddhism from its cultural and historical context, turning it into a spiritual lens for critical thought.

These types of interpretations caught on in historically Buddhist nations as well. Local Buddhist scholars validated these readings of the faith, but mostly (it seems) as a means of elevating Buddhism against colonialists, Christians, modernists and others who claimed, implicitly or explicitly, that it was a primitive tradition of irrational bowing, scraping and chanting that needed to be done away with. The book Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West (2003) by Judith Snodgrass, an Asia scholar at Western Sydney University, contains a fascinating chapter on how Buddhist intellectuals in Meiji-era Japan toured Olcott around the nation as a white Western defence of their faith, while silently scoffing at him as a dumb novice who presumed to tell them about their intellectual tradition.

Despite the disdain of old-school practitioners, some Asian scholars actually took to the Western interpretation of Buddhism. It influenced individuals such as D T Suzuki, a young Japanese intellectual who trained in traditional, hierarchical, ritualistic Zen but fell in love with Carus’s works, and came to the US in the 1890s to work for him. Later, Suzuki returned to Japan and spent much of the early 20th century teaching a stripped-back and psychological Zen, highly influenced by Carus and company. But he maintained contacts in the West, and in the 1950s undertook a US lecture tour, bumping into the Beats and other counterculture types who fell in love with his practical and personally accessible spirituality. This process of dissemination – in which Western views of Buddhism were taken back to Buddhist cultures, and then around to the West again – has repeated multiple times.

Today, most Westerners start out steeped in this stripped-back understanding of Buddhism, originally reconstructed in the West, honed down to a focus on personal mindfulness accessible to all, regardless of their other spiritual beliefs.

Debates rage about how to view this status quo. Some say that it’s fine for the faith to adjust to new contexts. Others argue that this Western flavour of Buddhism has shed vital components, such as a thorough understanding of rebirth or the value of a monastic institution as a place to foster journeys towards enlightenment. Instead, some arguments run, we’ve enabled the use of Buddhist tools to reinforce structures that lead to suffering – for instance, Buddhist-based mindfulness practices are used to teach dissatisfied cogs in corporate or social systems to suck it up and move along.

Whether we buy into such critiques or not, this modern Western Buddhism tends to eclipse from view the traditional Buddhist communities thriving in the US and abroad. Wendy Cadge, a religious sociologist at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, notes that even temples serving both traditional and new American communities often hold parallel but entirely separate services for each, with little interaction between the two. She recalls stories of Thai meditation retreats for Western Buddhists, where traditional Thai Buddhists would occasionally show up and practise their faith as they knew it, prompting the Westerners to complain that their authentic Buddhist experience was being ruined.

Westerners encountering Tibetan Buddhism in the late-19th century painted it as the opposite of the pure faith they had come to know. With its inexplicable use of magic rituals to ‘shape energy’ and change the world, with its monastic hierarchies and broad compendium of living gods, Tibetan Buddhism seemed to them an especially corrupted tradition – so much so that it couldn’t even be called Buddhism. They instead derisively referred to it as Lamaism, a reference to Lamas, elevated Tibetan teachers whom Western observers saw as a hostile and remote priesthood demanding unyielding subservience from others.

Tibet the country, meanwhile, had mystique unto itself. Cut off physically and politically from much of the world, it allowed for fantasies of a mystic utopia untouched by the ailments of modern society, as portrayed in the novel Lost Horizon (1933) by James Hilton and its 1937 movie adaptation. When Tibet fell to Communist China in 1950, many eulogised the loss of this imagined utopia. And when the Dalai Lama and a mass exodus of Tibetan Buddhists fled the nation in 1959, that set off a flurry of interest. ‘The Beatles are talking about him, and there’s this whole 1960s thing around the Dalai Lama before he’s even gone public and come to America,’ said Lopez.

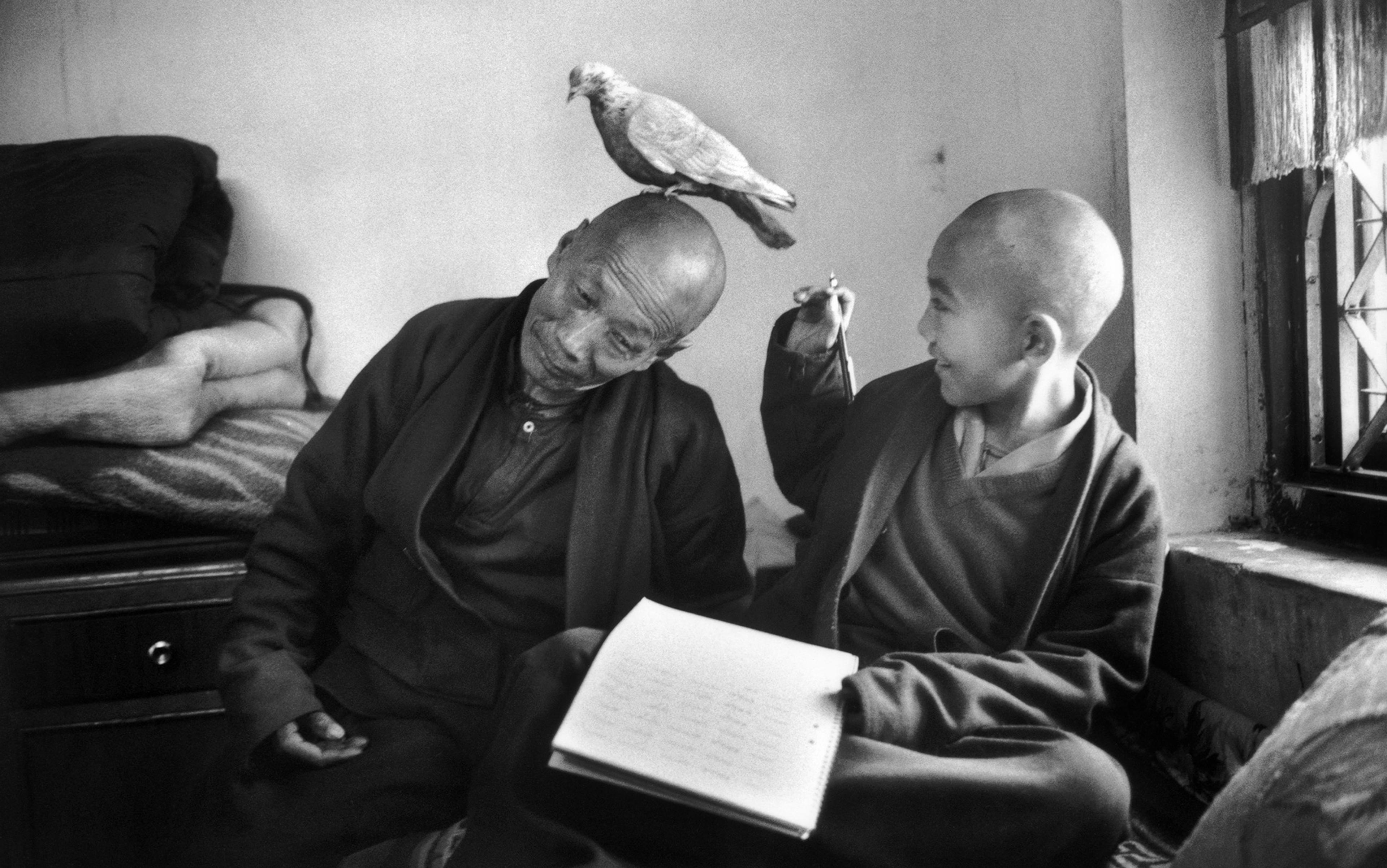

Slowly, Tibetan Buddhists filtered into the West. But they were unlike the Buddhists who had attracted mass public attention before them. Instead of arriving in scattered groups or one by one, they came with their full hierarchy intact; learned teachers and their students left their homeland together, and continued to stress the importance of everyday rituals and esoteric traditions such as tantric rites. The Dalai Lama’s first book was The Opening of the Wisdom-Eye, written in exile in 1963. It was a thoroughly traditional piece of Tibetan Buddhist rhetoric dissecting and discussing the faith’s various schools of thought, with no nods to Western-minded audiences. In the face of an outright war on their faith and culture in Chinese-controlled Tibet, the primary goal of most refugees was maintaining the integrity of their unique Buddhism, not merging with common perceptions of Buddhism in their new host countries.

This idealistic vision allows people to advocate for Tibet, which is what leaders such as the Dalai Lama want

Yet while Tibetan Buddhism in the US retains much that challenges Western conceptions of Buddhism, the Dalai Lama – the key Tibetan Buddhist voice in the West – never tries to explode our preconceptions. The first time he came to the States, in 1979, he gave a few fairly esoteric lectures on the fine-grained details of the faith, and they bombed. The next time he showed up, in 1987, he’d switched gears to focus on political activism for Tibetan autonomy via non-violent resistance based in faith. His goal is demystifying the Tibetan Buddhist civilisation he’s trying to protect, and building sympathy for it. He does so by focusing on its most universalisable and, to us, comprehensible aspects. He speaks of Tibetan Buddhism as one path among many by which to live ethically and reach core truths, encouraging people to stick with their own faith rather than convert.

‘In addresses to Western audiences, he often downplays the ritual, cosmological and metaphysical elements’ – many of the things that make Tibetan Buddhism so unique – noted David McMahan, a leading scholar of Buddhist modernism at Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania. ‘He focuses on kindness, universal responsibility, and, of late, secular ethics.’ This messaging takes a path of least resistance to square his faith with sympathetic preconceptions already ingrained in the West.

Other Tibetan Buddhist leaders, meanwhile, have taught full-blown Tibetan Buddhism with a Western spin. Chögyam Trungpa, who made it to the US a few years before the Dalai Lama, fused his traditional form of Buddhism, including tantric practices, with pop-Western ideas such as the quest for mental wellness. He shifted Buddhist language about desire and suffering into the Western framework of ego and neurosis. Other Tibetan teachers in the West transformed their pantheon of deities, at once symbolic of internal states and real beings to many, into stand-ins for psychological forces such as greed or the Id, a shift McMahan calls the ‘price of admission to the West’.

In short, it’s possible to engage the full complexity of Tibetan Buddhism in the US. Tibetan Buddhists are out there, doing what they’ve always done, and often willing to speak candidly about it. But it’s just as easy to take the Dalai Lama’s broad rhetoric, the teachings of Tibetans who accommodate Western mindsets, and wrap them all into the wider mainstream US view of Buddhism as a harmless, rational way of life. Add to that the utopian myth of Tibet, the sympathetic victimisation of the Chinese invasion, and the widespread belief that rituals are just exotic cultural garnish surrounding a simple core of wisdom, and you get the uncomplicated mainstream understanding of Tibetan Buddhism: a monolithic tradition of smiling, peaceful monks telling us how to live a broadly good life. This idealistic vision allows people to advocate for Tibet, which is what leaders such as the Dalai Lama want. And if Americans want to get involved in Tibetan Buddhism, then they can do so on their own terms – forming another hybrid American Buddhist tradition along the way.

So, where’s the harm? Not everyone wants to be defined by another culture’s needs. ‘You’ve had Tibetan filmmakers and activists who say: “If you prick me, I bleed,”’ said Michael Jerryson, a religious studies expert at Youngstown State University in Ohio, ‘because they realise they are not seen as being people anymore. They’re seen as these shiny, happy, two-dimensional characters.’ Jerryson equates this to the pain of positive yet still reductive stereotypes for other model minorities, such as Chinese Americans.

And it’s never fun to be the person whose practice of their traditional faith runs afoul of an outsider’s idealisation of it. In 2016, Ben Joffe, a cultural anthropology postgrad at the University of Colorado Boulder, told me about a growing number of confrontations between young Tibetans and Western converts to the tradition, with the former often accusing the latter of appropriation, and the latter accusing the former of mangling their own traditions. ‘It gets really, really ugly,’ he said.

Idealised visions of religions can also prevent us from recognising and reacting to the darker sides of their complex realities. Case in point, for about five years Westerners have been struggling with how to conceive of ethnic violence committed or advocated by Buddhists in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and other nations because it doesn’t square with our image of Buddhism. Ignoring, or ignorant of, the history and theological justifications of violence in Buddhism, we insist that the violence we’re witnessing is wholly unrelated to faith. They’re not real Buddhists; they’re not good Buddhists. That, Jerryson argues, prevents us from engaging with a whole set of variables that would make it easier to respond to such violence.

Buddhism’s image in pop culture is woefully deficient, more a reflection of our own history, culture and needs

And there’s going to be a lot we need to recognise and react to in Tibetan Buddhist communities in the coming years. For ages, Tibetan Buddhists inside and outside of Chinese-controlled Tibet have been exemplars of non-violence, in accordance with Western visions of their tradition, largely because the Dalai Lama has asked them to exercise restraint, and respect for him runs deep. But new movements are bubbling up, questioning the validity of the Dalai Lama’s path for Tibet, and exploring other forms of resistance – perhaps violent ones that could throw us into a state of confusion, like other forms of Buddhist-led violence, about how to react.

That could be a problem for Tibet and Buddhism because, as Jerryson notes, two-dimensional caricatures tend not to deepen. Instead, they flip – in this case, from loving and peaceful back to the sinister and violent caricatures that defined Lamaism to early Westerners. We’ve already seen this flip come into play on a small scale, when Westerners with little understanding of the details of Tibetan Buddhism try to enter the practice, become disillusioned with its ritual, hierarchy and esotericism, then take to the web to denounce the faith in anti-Lamaist terms. It is easy for Chinese propaganda to seize upon such disillusioned critiques as proof that they needed to invade in 1950, because the independent Buddhist nation of Tibet was a dark place dominated by a deeply flawed theocracy.

No one can or should expect every American to suddenly bone up on the finer details of the Bardo, the realm that Tibetan Buddhism believes we inhabit between death and reincarnation, or other nuanced aspects of this highly nuanced faith. That understanding takes a lifetime of practice, which few will ever have the luxury or the inclination to explore. But we can and should recognise that the ways we represent Buddhism in pop culture or talk about it casually are woefully deficient and overly simplistic, more reflections of our own history, culture and needs in many ways than of the faith itself. We should start by prefacing our broad statements about an entire faith with a few caveats. By doing so, we lose nothing of the Buddhist culture we have invented here in the West, and gain deeper understanding of the world and a culture beyond our own.