Listen to this essay

The liberal international order or Pax Americana, the world order built by the United States after the Second World War, is coming to an end. Not surprisingly, this has led to fears of disorder and chaos and, even worse, impending Chinese hegemony or Pax Sinica. Importantly, this mode of thinking that envisages the necessity of a dominant or hegemonic power underwriting global stability was developed by 20th-century US scholars of international relations, and is known as the hegemonic stability theory (HST).

In particular, hegemonic stability theory developed out of the work of the American economist Charles P Kindleberger. In his acclaimed book The World in Depression 1929-1939 (1973), Kindleberger argued that: ‘The world economic system was unstable unless some country stabilised it,’ and that, in 1929, ‘the British couldn’t and the United States wouldn’t.’ While Kindleberger was mainly concerned with economic order, his view was transformed by international relations scholars to associate hegemony with all sorts of things. In particular, a hegemonic power is generally expected to perform one or all of three main roles: first, as the dominant military power that ensures peace and stability; second, as the central economic actor within the global system; and third, as a cultural and ideational leader – either actively disseminating its political ideas across the system or serving as a model that others seek to emulate.

HST extends to all aspects of Pax Americana, and US naval power is seen as a ‘public good’ provided by the hegemon that secures the world’s maritime commons. However, many thinkers now see China’s growing power, especially naval power, as a consequential challenge to the US-led liberal international order, and fear that this assault on US hegemony portends disorder. The return of the US president Donald Trump to the White House has of course accentuated these liberal fears, especially in the US but also among America’s allies, particularly its Western partners. The premise of HST, crafted by Americans at the height of the American century, however, is wrong. History shows us that there are other pathways to international order, and that stability does not require hegemony. Maritime Asia’s long history indicates that, contrary to this American theory about international orders, a hegemon is not required for a functioning world order.

Since international relations theory emerged in the modern world with the rise of European power, it has tended to naturalise and universalise Western historical experiences. Western international relations scholars like to look towards classical Rome as the paradigmatic case of a hegemonic navy. The Roman navy had underwritten the stability of a maritime trading system, the Mediterranean. Anglo-American elites were educated to see the Pax Britannica in the 19th century and the Pax Americana after the mid-20th century as based on, and the rightful successors to, the Pax Romana in the classical Mediterranean.

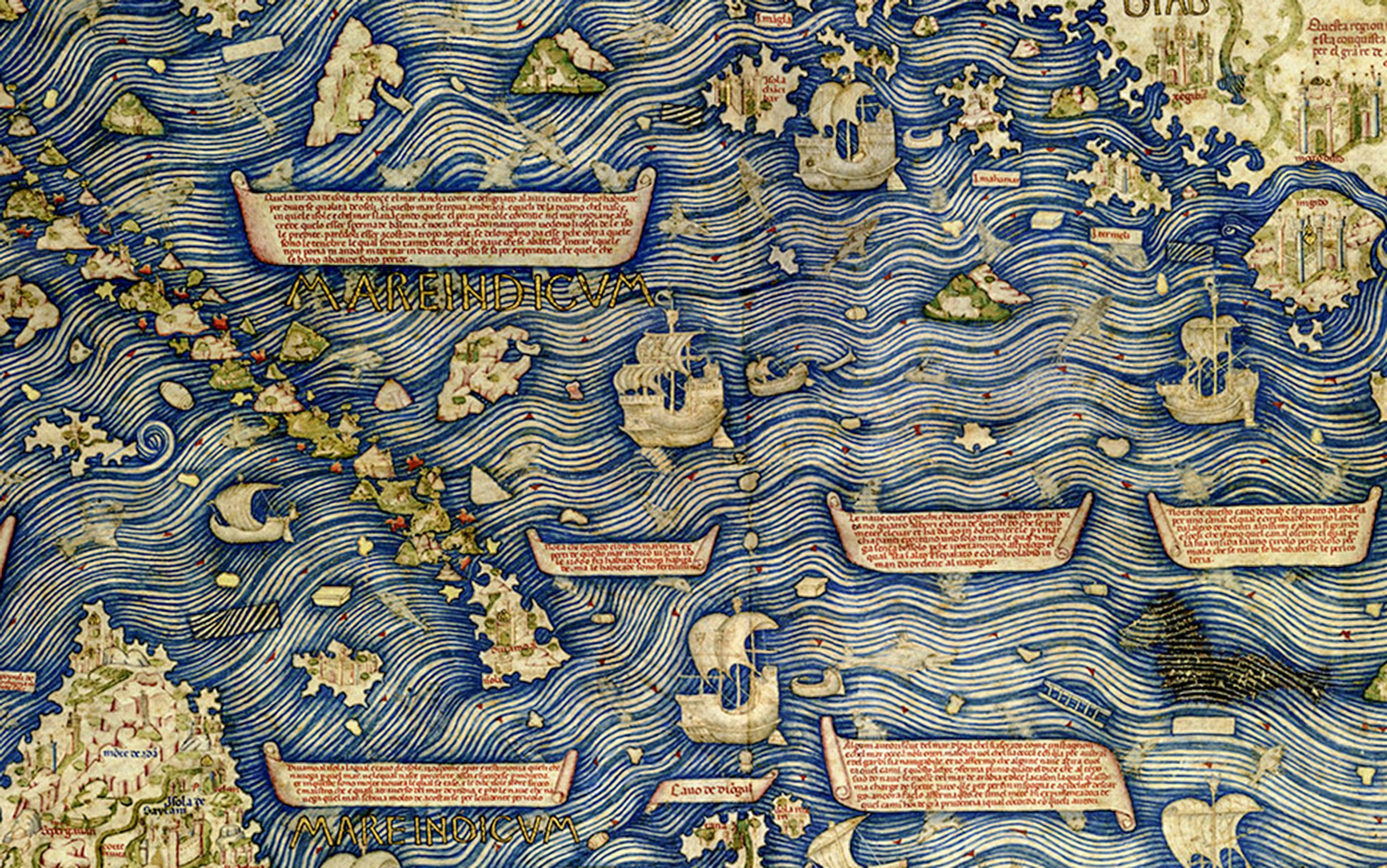

World map by Fra Mauro, c1450. Courtesy Biblioteca Marciana, Venice

But there is no law requiring we use the history of the classical Mediterranean under Roman hegemony as the model for understanding the history or theory of international relations. We recently wrote a book showing how the classical eastern Indian Ocean from around the 1st to the 15th centuries CE, corresponding with modern Southeast Asia, constitutes a coherent world order with appealing features. Of course, because this Asian world order existed before the arrival of the European imperial powers, international relations scholars are only now beginning to appreciate how it provided long-term stability in the absence of hegemonic power, and in particular how it emerged from the crucial role of the regional powers (or non-hegemonic powers) in that system. We think that it provides a powerful model for the world order emerging now, after US hegemony. It’s what we call a multiplex order, with the classical eastern Indian Ocean providing the paradigmatic case. It gave maritime Asia a durable, stable pattern of interactions among a group of states without a hegemon or world power dictating terms.

By the beginning of the Common Era, the oceanic corridor between the manufacturing powers of China and India was the most dynamic part of the world economy. Some leading global historians even claim that Asia enjoyed ‘an economic edge’ over Western Europe until as late as the Industrial Revolution (c1800). According to the British historian Angus Maddison, China and India may have accounted for half of the world’s GDP during these 18 centuries. Southeast Asia – the space between China and India – was central to the maritime world connecting these two economic powerhouses.

Originally, in the second half of the 1st millennium BCE, it was the Southeast Asians, especially those from the Austronesian groups, who pioneered the sea routes to China and India. For centuries, they played a key role in connecting the eastern Indian Ocean world. Since at least the mid-1st millennium BCE, Southeast Asians traded with China and India on ships of their own design that sailed using local Southeast Asian navigational techniques. According to a Chinese source from the 3rd century CE, Southeast Asian ships, probably from what is today Indonesia, were more than 50 metres long, and could carry 600-700 passengers along with 600 tons of cargo. By the 8th century CE, they could carry more than 1,000 people.

Southeast Asian shipping was the key to the maritime links between China and India, especially until the beginning of the 2nd millennium. For example, the Han emperor Wudi’s embassy to Huangzhi (Kanchi) in southern India in the 2nd century BCE travelled there on Austronesian ships. Another Han mission to Huangzhi at the start of the Common Era also ‘did not travel on Chinese ships’, meaning almost certainly Austronesian ships. Similarly, Yijing, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim who visited the Sriwijayan kingdom on Sumatra in the 7th century CE, travelled onwards to Tamralipti in eastern India along the Bay of Bengal on a royal ship of the maharaja (king) of Sriwijaya. Archaeological and literary records confirm that the ‘large ships and trading fleets’ of the Southeast Asian kingdoms sailed between the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea well into the first half of the 2nd millennium. Southeast Asian shipmasters played a central role along these shipping and commercial networks.

Southeast Asian polities vigorously competed for maritime trade. However, unlike the Roman Mediterranean, the eastern Indian Ocean lacked a hegemonic naval power that dominated entire trade routes. While Southeast Asian mandala kingdoms – a decentralised system of government, named after the Hindu and Buddhist designs featuring a circle within a square – engaged in commercial rivalries and warfare, no Southeast Asian polity was able to control the entire maritime route stretching from the South China Sea into the Bay of Bengal. There was no naval hegemon in this maritime world. This was at least partly related to the nature of the mandala political organisation and the associated practices of warfare in Southeast Asia. The ‘mandala polity’, a term theorised by the British historian O W Wolters, refers to the realm of authority of a king whose power radiated from a centre and included other similar rulers lower in the hierarchy. The power of a mandala ruler diminished with distance and/or overlapped with the edges of the authority of other mandala kingdoms.

No one exerted hegemony in these waters after 1025, but maritime trade continued to flourish

Throughout the classical period, Southeast Asia was the realm of hundreds of mandalas, some larger than others. The mandala system not only asserted autonomy from larger regional powers, such as those in China and India, it also created a stable international order until the mid-2nd millennium CE, when it was disrupted by the advent of European colonisation of the region. The mandala kingdoms rose and fell as they competed for maritime trade, but defeated polities were not bureaucratically or territorially incorporated into the realm of the winner. Instead, the losing monarch was materially and ritually subordinated to the victorious monarch as a lower ruler. As a result, Southeast Asian rulers aimed only to control their local waters, as opposed to dominating the entire long-distance maritime trade routes between China and India. In this interactive and interconnected world, if one local mandala disappeared, another assumed its nodal position.

The Sriwijaya mandala that emerged in Sumatra in the 7th century CE may represent an anomaly that nonetheless reinforces the broader pattern. By trying to dominate the Strait of Malacca, Sriwijaya may have attempted to control all trade between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. Substantial resistance to Sriwijayan efforts arose, however, from other polities along that Strait. Furthermore, other mandala kingdoms, the Heling kingdom in Java, and the Champa kingdom in present-day southern Vietnam, for example, had dispatched more tribute missions to China than had Sriwijaya during the Tang Empire. In other words, claims of Sriwijaya’s control of the Strait of Malacca are probably exaggerated, although it certainly exercised some form of mandala-like influence there. Importantly, maritime trade between India and China through Southeast Asia had flourished both before the rise of Sriwijaya in the 7th century and continued even after Sriwijaya’s peak in the 11th century. Therefore, even if Sriwijaya had temporarily exercised some form of hegemony in the Strait of Malacca, it was clearly not necessary to make that trading system work. Notably, the Strait of Malacca was just one segment – albeit an important one – of the trading world of the eastern Indian Ocean between China and India. Other important sea passageways between India and China included the Sunda Strait and the Lombok Strait, and a combination of maritime and overland routes via the Thai-Malay peninsula and across the Bay of Bengal into Myanmar and southern China. No Southeast Asian polity was able to dominate the entire network.

Great power intervention by the Indic and Sinic polities also did not lead to hegemonic domination (or sea control) over the entire eastern Indian Ocean world. The most important Indian military campaigns in Southeast Asia were the attacks carried out by the Chola Empire in the 11th century, in 1017, 1025, and the 1070s. Allegedly, the Cholas were retaliating against Sriwijayan interference in Chola trade with China. One of the most important outcomes of the invasion of 1025 was the Chola control of the Kedah port of Sriwijaya at the northern end of the Strait of Malacca. However, the Chola did not control the southern edges of this Strait, and consequently did not control the Strait of Malacca either. At the same time, they also destroyed the Sriwijayan pretence to hegemony in the Strait. No one exerted hegemony in these waters after 1025, but maritime trade continued to flourish.

Indian traders had sailed the waters of maritime Asia alongside their Southeast Asian counterparts since the beginning of the Common Era. By contrast, Chinese traders largely played a passive role until 1090, in the Song period. Prior to this time, it was these overseas traders whose shipping and commercial networks extended to China rather than Chinese networks extending overseas. The entry of the Chinese traders into this commercial world happened in the absence of coercion, and an oceangoing Chinese navy was created only in 1132. As the 12th-century Chinese built their powerful fleet, they ‘adopted some of the skills of their southern neighbours’, learning greatly from Southeast Asian shipbuilding, writes the French archaeologist Pierre-Yves Manguin. The Song entry into maritime trade at a new scale brought the state much revenue but may have also contributed to its fiscal challenges. The Chinese state’s growing consumption of goods from the eastern Indian Ocean world resulted in a substantial outflow of money from China. Despite their massive navy – the Song navy was probably the largest in the world then – they did not attempt to conquer Southeast Asia. The Song saw their navy primarily as a defensive force against the northern Mongols, to whom they ultimately lost with the Mongol conquest of China.

Unlike Sriwijaya and the Song, the Mongols truly aspired to world conquest. In the 13th century, they sent massive naval expeditions to Champa and Java, and dispatched maritime embassies to southern India, compelling them to submit to Mongol authority. In 1292-93, in an attempt to conquer Java, the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty in China sent 1,000 ships and 20,000 soldiers along with cavalry. Despite their impressive fleet, the Mongol campaigns in maritime Southeast Asia failed. The Yuan naval thrust was driven by political ideology of world conquest, not economics, and they did not attempt to restructure the trade patterns in Southeast Asia. The Mongols were unable to dominate ‘even a sizeable section of the maritime routes, much less the whole’, as the American historian Thomas T Allsen put it.

In the late 14th and the early 15th centuries, the Chinese rulers of the subsequent early Ming dynasty sought to outdo their Mongol-Yuan predecessors by attempting to bring the entire eastern Indian Ocean world under the so-called ‘tribute system’. They even sought to extend Ming influence into the western Indian Ocean. The massive Zheng He naval expeditions (between 1405-33) may also have attempted to control and regulate maritime trade in Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, yet the Ming economy did not depend upon maritime commerce. The early Ming state’s revenue came from land tax (not maritime trade), and the naval expeditions were not launched to support the ethnic Chinese traders in that region. Instead, the Ming expeditions sought to display the power and status of China in maritime Asia and beyond. According to the American historian Edward Dreyer, neither Zheng He nor the early Ming emperors ‘had any theory of sea power’, and the Asia scholar Tansen Sen has noted that the Zheng He ‘encounters’ were an exception as they ‘differed significantly from those of previous periods and were never replicated again by any future court in China.’ So, even as China became active in the eastern Indian Ocean during the Song, Yuan and early Ming, regional trade was not carried out under the aegis of the Chinese state or navy.

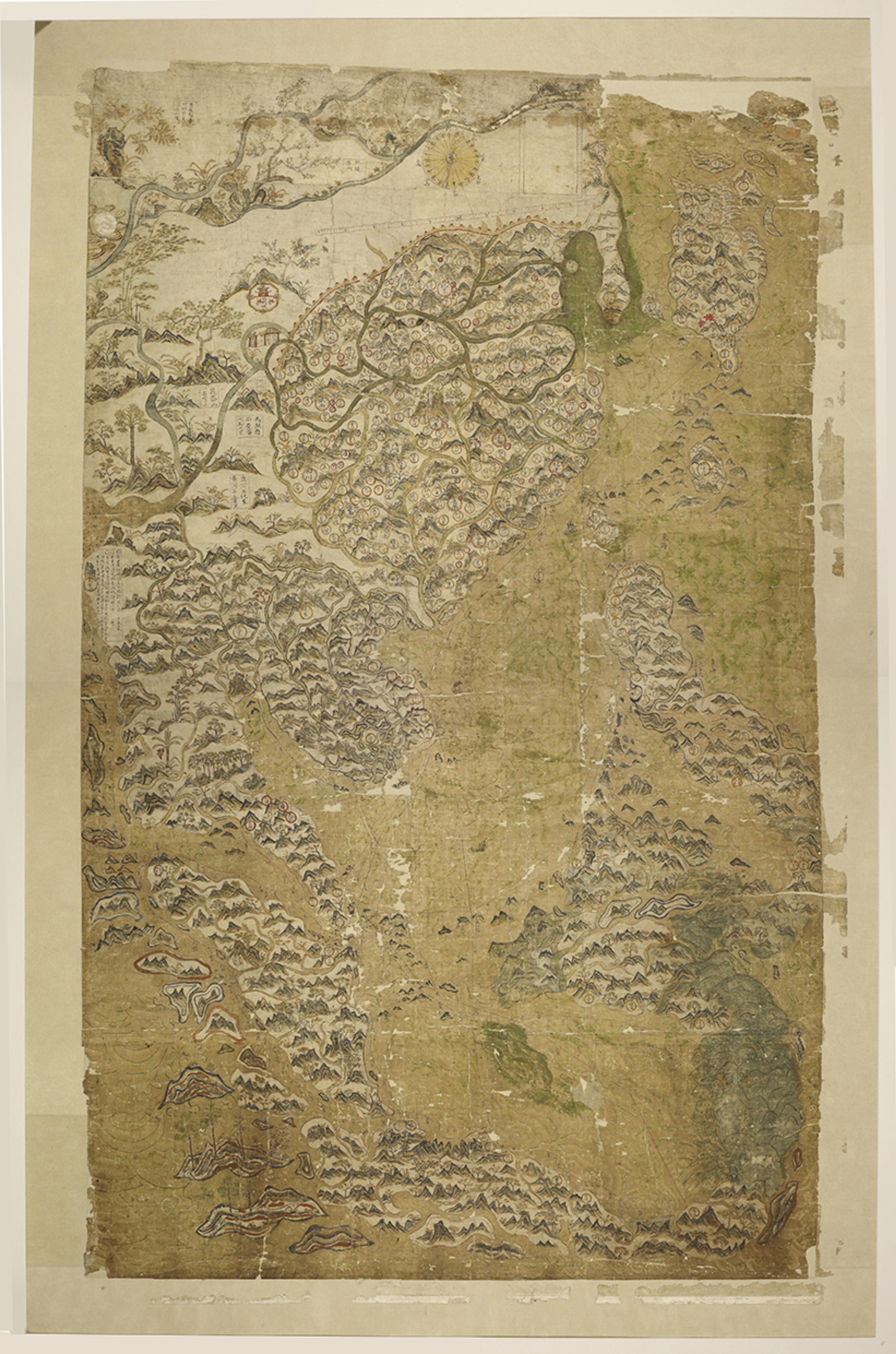

The Selden Map of China (c1620), painted with watercolours and ink on Chinese paper, is a unique example of Chinese merchant cartography depicting a network of shipping routes starting from the port of Quanzhou, Fujian province, and reaching as far as Japan and Indonesia. Courtesy the Bodleian Library, Oxford

The ethnic Chinese had begun settling in Southeast Asia from the Song period onward. But China’s naval activities during the Song, Yuan and early Ming were not undertaken for supporting the commercial interests of these Chinese traders. While their presence certainly boosted commerce in the eastern Indian Ocean, the ethnic Chinese merchants did not dominate this trade. In fact, no single state or ethnic group held exclusive dominance over the maritime commerce of the eastern Indian Ocean.

During these 15 centuries, no polity – not even imperial China – played the role of a hegemonic stabiliser in the eastern Indian Ocean world. Judged by the three main roles of hegemonic stability theory – ie, by their security, economic or cultural/ideational domains – there was no hegemon in the classical eastern Indian Ocean. First, there was no naval hegemon or a Pax Sinica in this maritime world. The mandala polities of Southeast Asia continued to fight and compete for maritime trade linked to state-making. For example, Angkor and Champa were vigorous rivals, and Angkor may even have entered into an entente with the south Indian Cholas prior to their attack on Sriwijaya in the early 11th century. Before the emergence of China as a maritime power under the Song, China sought to manage this commercial world only rhetorically by issuing instructions to its Southeast Asian ‘tributaries’. However, the writ of such Chinese power was largely limited to the Chinese end of this maritime world as it dictated the mode of interaction with China, as opposed to establishing the rules for this system. Meanwhile, conflict between the mandala polities continued. Later, under the Mongol-Yuan and the early Ming, it was imperial China itself that was the source of large-scale coercion and warfare, as opposed to facilitating the establishment of Pax Sinica as posited by the hegemonic stability theory.

The mandala-style polity was not imposed by any Indic polity upon Southeast Asia through coercion

Second, despite some conflict and violence – between the mandala polities of Southeast Asia, and between these mandalas and their Indic and Sinic counterparts – maritime Asia was a commercially dynamic world with no single all-encompassing economic centre. China was not the economic centre of this commercial world. India was just as important, and within India several regions and polities competed for pride of place. China might have been the single largest economy of this system, especially during the periods of the large empires (Han, Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming). India, however, was the chief producer of one of the most important manufactured goods of the premodern world: cotton textiles. The American historian Stephen F Dale has argued that the so-called ‘Silk Road’ was the ‘Cotton Road’ in the reverse direction. Indian cotton cloth was being traded with Southeast Asia since the 1st century CE, and it was also included in the goods exchanged between the Southeast Asian polities and China. Even India, however, was neither ‘the undisputed head’ nor the ‘coordinator of the system’ of cotton textile trade. The Southeast Asian polities were not the peripheries of any Chinese or Indian economic hegemon. Southeast Asian shipping networks played the pivotal role in the process of maritime connectivity across the eastern Indian Ocean, and they also injected their own products into these commercial networks. Furthermore, Southeast Asia’s exports, especially spices and metals, were not the raw materials or inputs for the leading manufacturing industries of the Chinese and Indian centres.

Third and finally, the eastern Indian Ocean did not fall under China’s cultural or ideational domination during these 15 centuries. Hegemonic powers are known to extend, as the international affairs scholar Charles Kupchan put it, ‘the norms that provide order within their own polities’ to ‘their expanding spheres of influence’. However, Southeast Asia’s mandala kingdoms were Indic-influenced polities as opposed to Sinic-style centralised-bureaucratic states. The mandala-style polity was not imposed by any Indic polity upon Southeast Asia through coercion or imperialism. The so-called Indianisation of Southeast Asia was almost entirely pacific. The 11th-century Chola expeditions were launched centuries after the emergence of Funan in the 1st century CE. Funan, in present-day Cambodia and Vietnam, is widely regarded as the first Indianised polity of Southeast Asia. This mandala world thrived for centuries, and the Majapahit kingdom in eastern Java, the last of the major Indianised polities of Southeast Asia, survived until the 1530s.

Southeast Asians themselves had localised Indic ideas of statecraft and diplomacy to meet their own political, economic and social needs. State formation in this Indianised world of Southeast Asia did not depend upon formal recognition from any polity in the Indian subcontinent. An ambitious ruler of a mandala could achieve their goals by meticulously replicating the ideal Indic polity, as outlined in Sanskrit literary and Hindu-Buddhist politico-religious works, within their realm. This approach would not only attract subordinates but also foster a sense of ideological unity and purpose. The creation of these political forms entailed self-legitimising processes in Southeast Asia through deep interconnections with India. Angkor Wat, for example, a Hindu-Buddhist temple complex that is also the world’s largest religious structure, is located in Southeast Asia, in present-day Cambodia, as is Borobudur, the world’s largest Buddhist temple, which is in present-day Indonesia. Even as these monuments were inspired by Indic conceptions of kingship and statecraft, there is no Angkor Wat or Borobudur in India.

The rulers of Sriwijaya styled themselves as Buddhist chakravartins, or universal monarchs. In an embassy that was sent to China in 1017, a Sriwijayan ruler even referred to himself as the ‘King of Ocean Lands’. While China’s elites may have thought of the Southeast Asian polities as ‘vassals’ that were ‘policing the seas’ on behalf of the Chinese tianzi (‘Son of Heaven’ or universal emperor) to keep the trade routes open, this was little more than Sinocentric rhetoric. After all, in practice, the Chinese approached Southeast Asia and India ‘not as bearers of what they regarded as a superior civilisation but as seekers of sacred knowledge.’ For example, the Chinese Buddhist monk Yijing who was mentioned above had gone to Sriwijaya and India in the 7th century to study Sanskrit and learn about Buddhism, as opposed to spreading China’s civilisation in ‘barbarian’ lands. Similarly, while the Chinese may have perceived the Angkor polity as a ‘tributary’, the rulers of Angkor were not China’s political or cultural subordinates. In fact, analogous to China’s universal rulers, they also styled themselves as world conquerors and ‘Lords of the Earth’. Moreover, their accomplishments extended beyond the construction of monumental Hindu-Buddhist architecture, such as Angkor Wat. Their capital, also called Angkor, may have been the world’s largest pre-industrial city, given their advanced engineering and hydraulic capabilities.

It was the shared management of maritime Asia that provided stability

During these 15 centuries, the Chinese did not attempt to Sinicise Southeast Asia beyond Dai Viet (or northern Vietnam), which remained under the influence of various Chinese empires for a millennium until 938-939 CE. Even after that, for several centuries, it continued to be a part of the political aspirations of China’s elites who continued to harbour the ambition to re-conquer Dai Viet. However, beyond Dai Viet, Southeast Asia was an Indianised world. In 1415, when Dai Viet was under Ming occupation and Zheng He was sailing the Indian Ocean, the Cham ruler Virabhadravarman, in what is today southern Vietnam, performed Indic rituals during his consecration ceremony.

Nevertheless, it is also noteworthy that Southeast Asia was not a cultural periphery of India during these 15 centuries. Indic and Southeast Asian polities engaged as peers. For example, Atiśa, the prominent Indian Buddhist monk who propagated Buddhism in Tibet, had earlier studied with Southeast Asian Buddhist masters like Dharmakīrtiśrī in Sriwijaya in the 11th century. In other words, the Indians (and, indirectly, the Tibetans) also acquired knowledge from their Southeast Asian counterparts. Furthermore, as the Scottish historian William Dalrymple has observed, even as the south Indian Chola temples are five times larger than ‘anything that preceded them’, the temples of Angkor ‘dwarf their Indian contemporaries many times over’. Southeast Asian mandala kingdoms, governed by chakravartin rulers, were prominent political, economic and cultural centres in their own right. They were neither culturally inferior to their Indian counterparts nor politically subservient to China. Despite their distinct underpinnings, co-existence and mutually beneficial commercial interactions between the self-proclaimed Chinese Son of Heaven and the universal chakravartin rulers of the mandala polities continued for centuries.

In the absence of a hegemonic navy exercising sea control, it was the shared management of maritime Asia – as opposed to hegemonic management – that provided stability. This shared management emerged from the decentralised decisions of several great and lesser powers that collectively provided the public good of the security of the sea lanes in the eastern Indian Ocean. Sea power does not depend upon naval power alone, because it is also determined by the polity’s ‘maritime outlook and tradition’, as the international relations scholar Hedley Bull has argued. Sea power remained dispersed in the eastern Indian Ocean as explained above. The different actors of this decentred maritime world followed multitudes of practices out of their own self-interest in the pursuit of their distinct functional and social needs.

The Southeast Asians connected the eastern Indian Ocean with their ships and shipmasters while supplying these societies with local commodities. The eastward oriented Indic polities brought cotton textiles and other important manufactured goods, traders and political ideas. Even the so-called Chinese ‘tribute system’ managed the mode of interaction only at the Chinese end of that system. The ‘tribute’ was a ritual façade for commercial interaction with China in China. Through very different practices of statecraft, the Southeast Asian polities also established enduring trade relations with the Indic polities across the Bay of Bengal. And they conducted their relationships with each other based on Indic-influenced ideas of state-making and commerce, given their mandala political formations. So the Chinese ‘tribute system’ was merely one component of a much bigger interconnected eastern Indian Ocean world that flourished for centuries, all in the absence of a hegemonic power. The seas also remained free in the classical eastern Indian Ocean, even as states engaged in competition to control their respective local waters.

The classical eastern Indian Ocean challenges the hegemonic stability paradigm and shows that dense commercial and cultural interactions can hold international systems together. This multiplex order was neither hegemon-centric nor did it revolve around one, two or a few great powers. Multiplex orders are not dependent merely upon the material power of the actors because political ideas also matter. Furthermore, local actors – or the non-great powers – play active and formative roles in the making and shaping of multiplex orders. Thus conceptualised, the classical eastern Indian Ocean embodies a model in contrast to the classical Mediterranean during Roman hegemony. It also provides important insights into the emerging multiplex order in the contemporary Indo-Pacific as the US-led liberal international order passes.

It is possible to extrapolate from the classical eastern Indian Ocean to help us understand real-world transformations in the world today. We don’t need to remain stuck in US thinking about the need for a hegemon. We are not implying that history will repeat itself in this maritime world. However, as observed by Wang Gungwu, a noted historian of Asia, when ‘enough of the historical is knowable, that might go some way in preparing us for what individuals and societies might do in the future.’ History helps show us, in other words, the range of the possible, and in this way opens our minds.

Despite widespread fears, the rise of China as an Indo-Pacific naval power does not imply a Chinese counter-hegemonic bid to displace the ‘liberal’ hegemony of the US. Although the US remains the world’s single-largest economy, China overtook it as the world’s largest trading nation in 2013. By 2020, in terms of fleet size, the Chinese navy had also emerged as the world’s largest navy. China’s economic and military rise has attenuated US dominance, especially in maritime Asia, or the Indo-Pacific. It is however unlikely to lead to Chinese hegemony. There are several reasons for this, including China’s strategic geography, strong neighbours like Japan and India, and the fact that the US remains powerful and engaged in that region, including through its long-standing military alliances.

So decline of US hegemony in the Indo-Pacific does not mean the emergence of Chinese hegemony. More importantly, the absence of a hegemonic power in this region does not imply disorder. China and the US are competing over relative position or rank in the global order, and otherwise aim to secure their access to the regional maritime commons. Their geostrategic competition entails efforts of naval/power projection, not sea control, because hegemony is no longer viable. The US is seeking the capabilities to project power into the waters near China’s shores, while China is keen to project power into the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean to protect its own interests. Moreover, they are not the only major naval powers in that region because others such as India, Japan, Australia, France and the United Kingdom also form a part of the emerging regional dynamics. Importantly, China’s return to power is not ‘a singular event’. Asia is also witnessing of the growth of other power centres, including India.

Ideational pluralism is likely to be a hallmark of the region in the future

But above all, the region is seeing the diffusion of power, agency and legitimacy to regional actors in Southeast Asia and to regional organisations like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Consequently, local (Southeast Asian) initiative matters in this world of multiple great and regional powers. Regional norms embodied in ‘the ASEAN way’ are actively shaping the region’s politico-military and politico-economic interactions. Southeast Asian states are individually and collectively co-engaging and omni-enmeshing all the major powers while rejecting the hegemony of any single actor. The Southeast Asian states are also trying to limit great power rivalry by avoiding partnerships with the great powers based on domestic political ideologies and by giving all of them access to the region. Furthermore, many Southeast Asian states are also collectively contributing to the management of the maritime commons – the crucial local waterways – through local initiatives such as the Malacca Straits Patrols (jointly undertaken by Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand) and the Sulu-Sulawesi Seas Patrols (jointly undertaken by Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines). In other words, a non-hegemonic order is in the making in that region.

It is the accretion of the decentralised choices of these multiple great and regional powers that, collectively, produces the public goods of trade and security in the Indo-Pacific. Stated differently, a multiplex order with echoes of the classical eastern Indian Ocean is in the making in the Indo-Pacific today. This is a geopolitical space where Southeast Asia’s active agency was, and remains, constitutive. As such, the US is likely to be the last naval superpower to command the seas as our future is pointing towards a non-hegemonic world. As in the past when Indic, Southeast Asian (or localised Indic) and Sinic political systems co-existed, ideational pluralism is also likely to be a hallmark of the region in the future given the multiple political and economic systems in the Indo-Pacific.

The passing of the US-led liberal international order is not to be feared, and a multiplex order is already taking shape today. The classical eastern Indian Ocean world has things to teach us about the 21st century. So too do other histories, which can assist us in overcoming the biases that arose in thinking about international relations and world orders from universalising propositions that were developed during the Cold War. The global and historical approach to international relations also avoids the impulse to counter 20th-century US-centric theories with Sinocentrism or Indocentrism. The historical eastern Indian Ocean enables us to think about the present and the future in novel ways that might help us make better decisions and build a stable and prosperous world order.

This essay is based on the authors’ book Divergent Worlds: What the Ancient Mediterranean and Indian Ocean Can Tell Us About the Future of International Order, published by Yale University Press in 2025.