In the late 1980s, my father and his friend got pulled over by an East German police officer. They had inadvertently taken a wrong turn, leaving the international road that connected West Germany to West Berlin. After some frantic back-and-forth with the officer, they were allowed to turn back.

Things get a bit more harrowing when world leaders take a wrong turn.

In 1962, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev supplied Cuba’s Fidel Castro with long-range missiles capable of carrying a nuclear warhead, and almost triggered an all-out war. The presence of weapons this close to Washington, DC violated the spheres-of-influence logic that had emerged after the Second World War. The Soviet Union and the United States each constituted their own pole around which ideological, military and economic influence coalesced.

Since the Cold War touched every aspect of peoples’ lives – from my own father to Castro – academics, journalists and pundits became obsessed with understanding the international system the Cold War had created. A new academic discipline, called international relations theory, rode the enthusiasm surrounding scientific research in the 1950s and met the need for predictability in the face of nuclear Armageddon. Just two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, theorists like Kenneth Waltz said that the Cold War was making the international system safer. With only two poles, a balance of power was naturally bound to occur, he argued, because states integrate weaker states within their sphere of influence and divide the cake, creating fewer opportunities for conflict.

These so-called international relations theorists drew on ancient thinkers and history to predict behaviour that goes with a particular type of international system. Based on Thucydides’ account, the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens (431-404 BCE) came to be known as the first bipolar international system. Key political theorists like Alexis de Tocqueville, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche and Michael Oakeshott had already conceptualised politics as the struggle between two poles, and served as an inspiration for their colleagues who studied international politics. Yet, the precise origins of thinking in terms of bipolarity and world order are murky.

Ancient philosophers like Plato, who talked about political order, were followed by Church fathers like Augustine of Hippo who talked about the City of God, and Enlightenment thinkers like Immanuel Kant who believed two republics would never go to war with each other. Even as Cold War bipolarity became cemented in the minds of policymakers and university professors in the 1960s, there were always dissidents or contrarians from its consensus.

Already in 1944, but also after the Chinese Communist revolution of 1949, when Mao Zedong formally proclaimed the People’s Republic of China, the journalist Walter Lippman argued that China had an autonomous role, separate from the Soviets, and he viewed General Charles de Gaulle’s decision in 1966 to withdraw French troops from the military command structure of the US-dominated NATO as further proof of the end of the superpower dominance.

Boardgame thinking ignores that it’s people who determine what international affairs look like

Talk of a new international order tends to emerge at moments when new metrics for measuring power beyond hard indicators, such as military capacity and the amount of economic output, emerge to help better understand changing realities. In the 1970s, Japan’s economic growth, driven by technological advancements, positioned it as a potential major player in a multipolar world order, an argument further strengthened by the US withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973. The messy world of diplomacy is often reduced to a bloodless boardgame of players reacting to each other’s moves. The political scientist John Mearsheimer of the University of Chicago acquired global fame in February 2022 when a videoclip from 2015 resurfaced in which he predicted Russia invading Ukraine, simply because of geographical position and size difference.

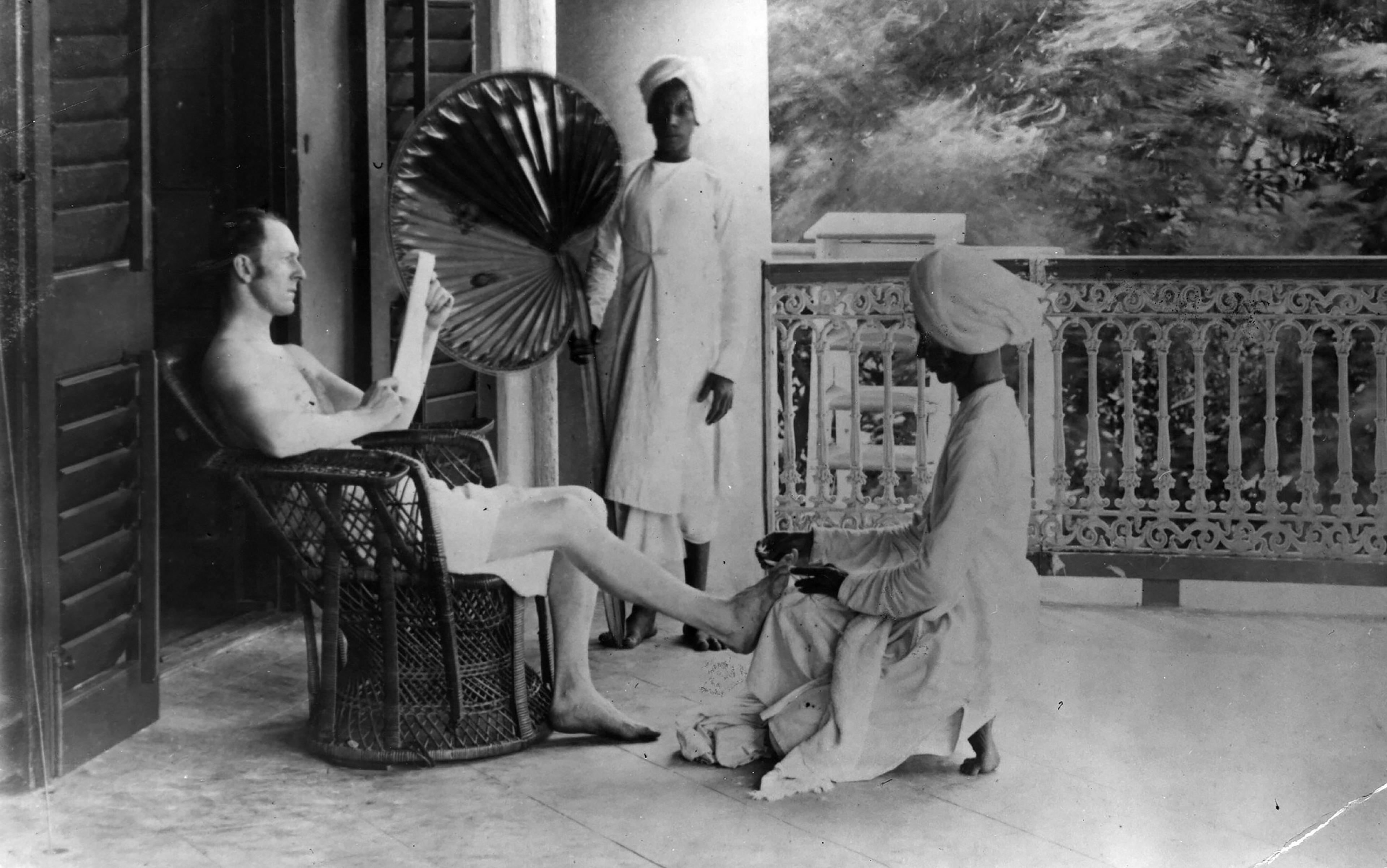

Boardgame thinking, however, ignores that it is people and their ideas that determine what the world and its international affairs look like. Talking about an international system as if it is a game of Stratego clings to the fiction of foreign affairs as armchair negotiations between moustached men who have to take only each others’ concerns into account. It makes light of the rise of mass democracies and the sudden emergence of new countries that expounded their own ideologies after 1945.

Decolonisation and postwar reconstruction led to an explosion of new worldviews, highlighting that power and spheres of influence could come only to those with an ideological project, aimed at convincing a mass audience. In the 1940s, governments became the providers of free education and social security schemes to accelerate reconstruction or postcolonial state-building. The GI Bill in the US, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom, free healthcare in the Soviet Union, or the Department of Social Welfare in the Gold Coast, which was taken over by Ghana after independence, all had to prove the viability of their respective capitalist, socialist, imperial or anticolonial ways of life. After 1945, power could not simply be wielded because it came from God, a monarchical lineage, or was legitimised by bourgeois clientelist structures. Power had to be mobilised in the service of something bigger: the creation of progress. The road to modernity was paved in places like the Soviet collective farm, the US supermarket or in the schools of recently independent countries in Africa and Asia.

This struggle for the soul of mankind made the world multipolar as the Cold War – Cuban Missile Crisis and all – intensified. Decolonisation – of India in 1947, or Indonesia in 1945 – exponentially increased the number of possible modernities that were available. The US and the USSR not only faced each other, but also competed with old European empires and – more importantly – newly independent states that were keen to spread their own social model to other parts of the decolonising world.

Postcolonial leaders did not simply undergo moves made by two players on a chessboard who provided development aid to pull them into a capitalist or a communist sphere of influence. Rather, politicians in Africa and Asia were engaged in a struggle with much higher stakes. They wanted to correct European modernity by destroying the civilising mission, the colonial idea that nonwhites were incapable of self-government, and by embracing precolonial tradition. One such leader, Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, spread pan-African modernity, propagating an ‘African personality’ while seeking to unite the continent. This African personality was coined by the Americo-Liberian educator Edward Wilmot Blyden in 1893 and promoted to make the case that African precolonial traditions were not inferior but had provided the basis for the modern world. Propaganda highlighted how Africans had engaged in science and technological innovations before the arrival of Europeans. Even the Gold Coast’s name, Ghana, derived from the Ghana Empire, which had been an economic powerhouse from the 6th to the 13th century.

Unlike communist, capitalist and imperial modernisation strategies, anticolonial modernity prioritised psychological liberation, responding to a pervasive sense that underdevelopment and imperialism were deeply psychological and cultural challenges. As anticolonial intellectuals like the psychiatrist Frantz Fanon, a key theorist of the Algerian War, argued in 1961: the ‘white man’ had robbed nonwhites of their self-worth and instilled psychological disease. Therefore, genuine progress required the restoration of self-confidence, the creation of a ‘new man’. Nkrumah also called upon freedom-fighters not to ignore the ‘spiritual side of the human personality’, because Africans’ ‘material needs’ made them vulnerable to subjugation.

Ghana did not shy away from projecting its brand of anticolonial modernity to other parts of Africa

In 1968, Julius Nyerere of Tanzania wanted education to liberate body and mind because ‘colonial education’ had ‘induced attitudes of human inequality.’ Whenever Soviet or US technical advisers arrived in a country they’d seen as embracing a precolonial tradition worthy of their aid, factories and dams got built while peasants were targeted because they represented tradition and supposedly slowed down the transformation of societies. In contrast, Nkrumah’s Ghana sent out special missions, like the one that left Accra on 11 November 1960 for Sudan, Kenya and Tanganyika to first study the ‘political consciousness’ and attitudes of different groups. No financial assistance should ever be given, mission delegates wrote, without first having conducted an on-the-spot analysis. Aloysius K Barden, the director of the Bureau of African Affairs in Ghana, and his team offered scholarships to Sudanese students because they possessed ‘the fire kindled by the youth’, while women were useful because of their wish to ‘exercise their political rights’. Africa could modernise on its own terms if a sense of African cultural uniqueness and pride was restored. The St Lucian economist Arthur Lewis was therefore flown into Ghana to devise an economic development strategy in line with Africa’s precolonial culture and history.

Similarly at the All-African Peoples’ Conference of December 1958, Nkrumah urged delegates to ‘develop’ the ‘African personality’ and not be ‘slavish imitators’ of other ‘ways of life’. The stress on psychology and culture in this conception of modernity meant foreign aid could be accepted from every quarter as long as it was complemented by ideological education in the service of psychological liberation: the freeing of Africans from their inferiority complex. As Tom Mboya claimed in 1961, Kenyans were ‘capable of gauging the ulterior motives’ of those who offered assistance. Moreover, Ghana did not shy away from projecting its brand of anticolonial modernity to other parts of Africa. While propping up the Ghanaian economy with British, US and Soviet funds, in September 1959 Nkrumah also set up a centre for psychological and cultural liberation from empire: Ghana’s Bureau of African Affairs. Besides relying on a printing press, library and linguistic secretariat to produce materials that conjured up a rich African past, the Bureau also produced movies that urged African countries to follow Ghana’s example by showing students and their lecturer in a building that was still under construction.

At the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute, foreign students were trained in ‘positive action’, Nkrumah’s brand of political organising, while socialism was struck from the curriculum to highlight the power of Ghana’s example of modernisation that fused African culture and progress.

Anticolonial modernity was not a response to the bipolar world but was rooted in the Haitian Revolution. In 1791, a rebellion of the enslaved, eventually led by the charismatic Black general Toussaint Louverture, demanded the universal application of the French Revolutionary principles of liberty and equality. In so doing, Haitians wanted to not only gain their freedom, but also correct European modernity. The Enlightenment, which had inspired French Revolutionaries, celebrated reason but was tainted by the racist belief that only whites possessed a capacity for it. African leaders came to draw on that ambition for inspiration to define the goal of their own ideological projects. They also attracted intellectuals from the Caribbean like Aimé Césaire, who was influential in Senegal, and George Padmore, who moved to Ghana at the end of his life in 1957. In revolutionary centres in Accra, Cairo and Dar es Salaam, an idealised ‘authentic’ image of the past, found in Pan-Arabism, Pan-Africanism or ‘Ujamaa’, was held up by freedom-fighters as an important corrective to European, Soviet and US modernity, which was exclusionary and racist.

Anticolonial modernity sought to create an international system that looked very different from the bipolar Cold War system. In the worldview of anticolonial leaders, the independence of former colonies was constantly under threat. Attaining a modernity that embraced tradition and liberated people psychologically required the creation of an African Union. This was not an empire, but a federation of liberation where small and fragile independent states could seek protection.

Third World nationalists built different types of federative and cooperative structures beyond their own postcolonial state to marshal the economic, cultural and political capacity required to attain modernity on the Global South’s terms. This is why Nkrumah believed independence was ‘meaningless’ unless it was ‘linked up totally’ with that of the ‘continent’. His finance minister Komla Agbeli Gbedemah agreed, declaring during his visit to India in September 1957 that freedom was ‘indivisible’. In the words of the All-African Peoples’ Conference steering-committee: ‘stable peace’ was ‘impossible in a world that’ was ‘politically half independent and half dependent’. If Ghana’s anticolonialism stopped at its borders, the country would not be able to remain independent.

Pan-Arabists wanted unification to reclaim the grandeur lost during Ottoman and Western occupations

Pan-African modernity had a continental focus, but aspired to remake the colonising world as a whole. In the words of the Trinidadian journalist and pan-African activist Cyril Lionel Robert James, ‘the modernisation necessary in the modern world’ could be attained only ‘in an African way’. The Federation of Liberation became a panacea for the colonial disease wherever it occurred. In 1962, in a letter to all the leaders of the disintegrating West Indian Federation, Nkrumah argued that ‘a united West Indies’ was the only way to deal with ‘problems created by colonialists’.

Instead of a superpower competition for the allegiance of newly independent states, which split the world in two, international relations in the 1950s and ’60s were in fact defined by old and new empires competing with many different federations of liberation. Pan-Africanism was only one of many pan-isms that sought the modernisation of member states, emerged in the 19th century, acquired political meaning after the First World War, and was revived in some way after the Second World War. Besides smaller federations, such as the United Arab Republic, the Ghana-Guinea Union, the Fédération du Mali, the Zanzibar-Tanganyika Union and the Arab-Maghreb Union, larger visions had a global impact. Pan-Arabists wanted unification to reclaim the grandeur lost during Ottoman and Western occupations.

Pan-Asian enthusiasts sought to build a federation of liberation to guard against Chinese or Japanese aggression. Pan-Americanism led to the Pan-American Union in 1890, which aspired to increase cooperation between the US and Latin America, but was adopted by el libertador Simón Bolívar who conceived of it as an anti-US line of defence. As Dane Kennedy writes, decolonisation was not ‘the collapse of colonial empires and the creation of new nation-states’. Rather, the post-1945 wave of independence created a world of federations that sought to bring other countries into their sphere of influence.

In short, in a decolonising world, people had more than communism and capitalism to choose from. Africa did not become the place where the Soviet and the US models competed for supremacy, but a destination for a ‘crowded safari’ as the British journalist Edward Crankshaw quipped in January 1960. The Observer even had to publish a guide to all of the African ‘isms’ to paint a clearer picture of the ‘ferment of ideas’. Anticolonial movements did not define themselves in opposition to or in alignment with US or Soviet ideology, but rather wanted to chart a truly different, inclusive route to progress. They took as a model the future promised by the Haitian Revolution.

The 20th century’s anticolonial revolutionaries resembled other radicals who had also vested their principles within the state institutions their revolutions produced. Marxists in the Soviet Union wanted to achieve the aims of the Bolshevik Revolution, capitalists in the US were eager to export the ideas of the American Revolution, and imperialists within European nation-states sought to spread the benefits of the Industrial Revolution. In ideological terms, therefore, the post-Second World War international order was one in which not only the USSR and the US had a sphere of influence. As French military staff acknowledged in April 1960, Ghana and Egypt had zones of influence on the continent, which Paris needed to take into account when planning operations.

While pan-African modernity might have faded in the background of common historical understanding, mid-20th-century contemporaries identified it as an alternative development model. ‘Africans’ regarded ‘Cold War issues as problems’ from which they remained ‘aloof and unaffected’; ‘[e]ven when the Cold War appears in their midst, they are reluctant to identify it as such,’ according to a US study of African attitudes in 1965. Already in 1960, the US State Department acknowledged that Africa was not primarily a Cold War problem, while the president Dwight D Eisenhower believed ‘nationalism was the most powerful force in the world today, and that the pull of independence was stronger than that of communism’.

Communist activities were seen as ancillary, at best, to the real problem, which was the ‘revolution of rising expectations’, the idea that unfulfilled, increased expectations create unstable political situations. Communism was a disease that could thrive in the development process. The US secretary of state John Foster Dulles therefore wanted to ‘pre-empt’ Africa ‘for the Bloc’. In 1968, Walt Rostow, US national security adviser to the president Lyndon B Johnson, recognised the appeal of pan-Africanism, pan-Asianism or pan-Americanism, and sought to control them. Many of the ‘postwar troubles’, he believed, ‘centred around men who were radical, ambitious revolutionaries, who carried maps in their heads of how they would like the world to look’. In Nkrumah’s map, he became ‘the Emperor Jones of Black Africa’.

In 1968, the incoming national security adviser Henry Kissinger wrote three essays on US foreign policy. He concluded that ‘the age of the superpowers’ was ‘drawing to an end’. ‘Military bipolarity’ had ‘actually encouraged political multipolarity’ because ‘weaker allies’ felt ‘protected by the rivalry of the superpowers’. ‘The new nations weigh little in the physical balance of power,’ he admitted. ‘But the forces unleashed in the emergence of so many new states may well affect the moral balance of the world – the convictions which form the structure for the world of tomorrow,’ which added ‘a new dimension to the problem of multipolarity.’ Kissinger was pessimistic about the ideological alternatives anticolonialism had created: ‘The greatest need of the contemporary international system is an agreed concept of order.’ Instead, ‘power is unrestrained by any consensus as to legitimacy; ideology and nationalism, in their different ways, deepen international schisms.’ He realised that the US had to adjust to the ‘political multipolarity of the late 1960s.’

If the pan-African project failed, modernisation would also be set back

The multipolar system that decolonisation had created also affected how international relations theory professors saw the world. In 1953, the influential international relations scholar Hans J Morgenthau, an arch realist and Jewish refugee to the US, warned against thinking in rigid Cold War terms when it came to African anticolonial struggles. Rather than choosing between ‘communist and non-communist revolution’, the US had to go beyond the bipolar logic and assess if the revolution it observed was in its ‘interests’ or not. Morgenthau maintained that Africa had little real power, but he also understood that not only superpowers mattered.

In 1965, the liberal international relations theorist Joseph Nye wrote about the appeal of pan-Africanism, which he described as a ‘modernising’ ideology ‘of its own’, allowing African countries to ‘take moralistic and critical positions on a wide number of world issues’. Nye understood that nonalignment was not only about not aligning yourself with one of the Cold War blocs, but more importantly allowed ‘pan-Africanists to be unabashedly eclectic in using outside ideas and institutions without suffering from a feeling of loss of independence in the process.’ Marxist theorists also questioned bipolar rigidity. Immanuel Wallerstein wrote in 1961 that the ‘strength of the pan-African drive’ had to be ‘attributed precisely to the fact that it is a weapon of the modernisers’. If the pan-African project failed, modernisation would also be set back.

In short, theorists, policymakers and commentators in the Global North in the 1950s and ’60s came to realise that – in ideological terms – they were living in a multipolar world. Voices in the Global South might have become more visible today as information media have become more accessible and economies have grown but, from inception, from the invention of modernity in the Enlightenment, decolonised territories have been part of an international conversation about the meaning of international systems.

Postscript on sources

Recovering how pan-African modernity affects postwar international order requires historians to take African archives, rather than repositories in the metropole, as a starting point. Caution, however, is required since documents in African archives are not rare gems waiting to be unearthed by adventurous historians. Rather, the documents will make sense only when we think about how postcolonial archives can alter the findings that come from repositories in the metropole. Increased access to postcolonial archives has produced a rush for paper reminiscent of the opening up of Soviet archives in 1991 when historians often used new materials to confirm findings they had already drawn from US and European archives. This confirmation bias is strengthened by the nature of much of the postcolonial archive.

In the first years after independence, record-keeping was chaotic. In 1965, the Office of the President in Kenya ordered ‘all cabinet minutes and memoranda’ to ‘be destroyed.’ The National Archives in Nigeria purchased a dehumidifier in July 1960 which, based on the crumbled documents, is no longer in use today. Furthermore, the postwar archival infrastructure is highly national and reflects the fantasy that decolonisation’s impact could be confined to domestic politics.

This makes the archives of decolonisation difficult to locate and colonial crimes easy to hide. Critics have therefore questioned if it is at all possible to ignore the US preponderance in the post-1945 international system, particularly since easily accessible archives in the Global North remain overrepresented in many analyses of the Global South. The use of African sources, however, enables historians to actually test the extent of that power to shape the international system.