We should expunge, forever, the epithet ‘precolonial’ or any of its cognates from all aspects of the study of Africa and its phenomena. We should banish title phrases, names and characterisations of reality and ideas containing the word.

To those who might be put off by the severity of the proposal, or its ideological-police ring, I hear you and ask only that, with just a little patience, you hear me out. It will not take much to jolt us out of the present unthinking in assuming that ‘precolonial’ or ‘traditional’, and ‘indigenous’, has any worthwhile role to play in our attempt to track, describe, explain and make sense of African life and history.

When ‘precolonial’ is used for describing African ideas, processes, institutions and practices, through time, it misrepresents them. When deployed to explain African experience and institutions, and characterise the logic of their evolution through history, it is worthless and theoretically vacuous. The concept of ‘precolonial’ anything hides, it never discloses; it obscures, it never illuminates; it does not aid understanding in any manner, shape or form.

Let us begin with the fact that the ubiquitous phrase is almost exclusive in its application to Africa: ‘precolonial Africa’. How often do we encounter this designation in discourses about other continents? If not, what explains the peculiar representation – treating the continent as if it were a single unit of analysis – when it comes to Africa? I am afraid it comes from a not-so-kind genealogy that always takes Africa to be a simple place, homogenises its peoples and their history, and treats their politics and thought as if they were uncomplicated, each substitutable for the other across time and space. Once you are thinking of ‘Africa’ as a simple whole, it becomes easier to grossly misrepresent an entire continent in the temporal frame of ‘precolonial’.

In reality, ‘precolonial’ Africa never existed. It is a figment of the imagination of scholars, analysts, political types, for whom Africa is a homogeneous place that they need not think too hard about, much less explain to audiences. It was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, a racist philosopher, who argued in the 1820s that Africa was a land ‘outside of Time’ and not a part of the movement of ‘History’. Our intellectual forebears in the 19th century fought against this false characterisation. They were the first to remind people of the fact that Africa had always been a part of the movement of history and the global circuit of ideas. They knew what was behind Hegel’s effort to divide Africa into ‘Africa proper’, or ‘Black Africa’, and ‘European Africa’ – it was his need to reconcile his idea that Africa stood outside of history with the undeniable reality of the attainments of ancient Egypt. His ‘solution’ was to identify the achievements of Egyptian Africans as coming from exogenous sources and to remove it from ‘Africa proper’.

All who talk glibly about ‘precolonial’ Africa, insofar as the designation bespeaks a temporal horizon, award an undeserved victory to the racist philosopher. Of course, the ‘pre’ in ‘precolonial’ supposedly designates ‘a time before’ colonialism appeared on the continent. But how do we deign to describe a period from the beginning of time to the moment when the European, modernity-inflected colonial phenomenon showed up? It accords more of a mythological than a historical status to the arrival of modern European colonialism in Africa and its long and deep history. The ‘precolonial’ designation, in practice, even excludes two earlier European-inspired colonialisms in Africa. After all, for those of us who know our history, Roman and Byzantine/Ottoman colonial presences on the African continent were not without legacies on the continent, too.

Was ancient Egypt part of some precolonial formation? That strains credulity

For one thing, the role of African thinkers in the evolution of Christianity becomes elided by a periodisation that does not see a continuity between African events and events elsewhere, from Europe to Asia to the Americas. It also makes it difficult to track demographic continuities when it comes to cultural hybridities, including citizenship, in different parts of the Mediterranean continuum. And, as long as Roman colonialism lasted in North Africa, the region was not hermetically sealed from the rest of the continent, both across the Sahara, and east to the northern reaches of present-day Kenya.

As used, the term ‘precolonial’ Africa and the distortions it represents cannot illuminate our understanding of Africa and its history.

More importantly, it is wrong to think of colonialism as a non-African phenomenon that was only brought in from elsewhere and imposed on the continent. Africa has given rise to a rich tapestry of diverse colonialisms originating in different parts of the continent. How are we to understand them? For example, if ‘precolonial Morocco’ refers to the time before France colonised Morocco, it must deny that the 800-year Moorish colonisation of the Iberian Peninsula, much of present-day France and much of North Africa was a colonialism. For, if it were, then ‘colonial Morocco’ must predate ‘precolonial Morocco’. I do not know how any of this helps us understand the history of Morocco. Similarly, a ‘precolonial’ Egypt that refers to Egypt before modern European imperialism would also deny Mohammed Ali’s colonial adventures at the head of Egypt in southern Europe and Asia Minor. Was ancient Egypt part of some precolonial formation? That strains credulity. To conceive of the history of Africa and Africans in terms only, or primarily, of their relation to modern European empires disappears the history of Africans as colonisers of realms beyond the continent’s land borders, especially in Europe and Asia.

It is bad enough that the term distorts the history of African states’ involvement in overseas provinces. It is worse that it misdescribes the evolution of different African polities over time. The deployment of ‘precolonial Africa’ is undergirded by a few implausible assumptions. We assume either that there were no previous forms of colonialism in the continent, or that they do not matter. We talk as if colonialism was brought to Africa by Europe, after the 1884-85 Berlin West Africa Conference. But it takes only a pause to discover that this is false.

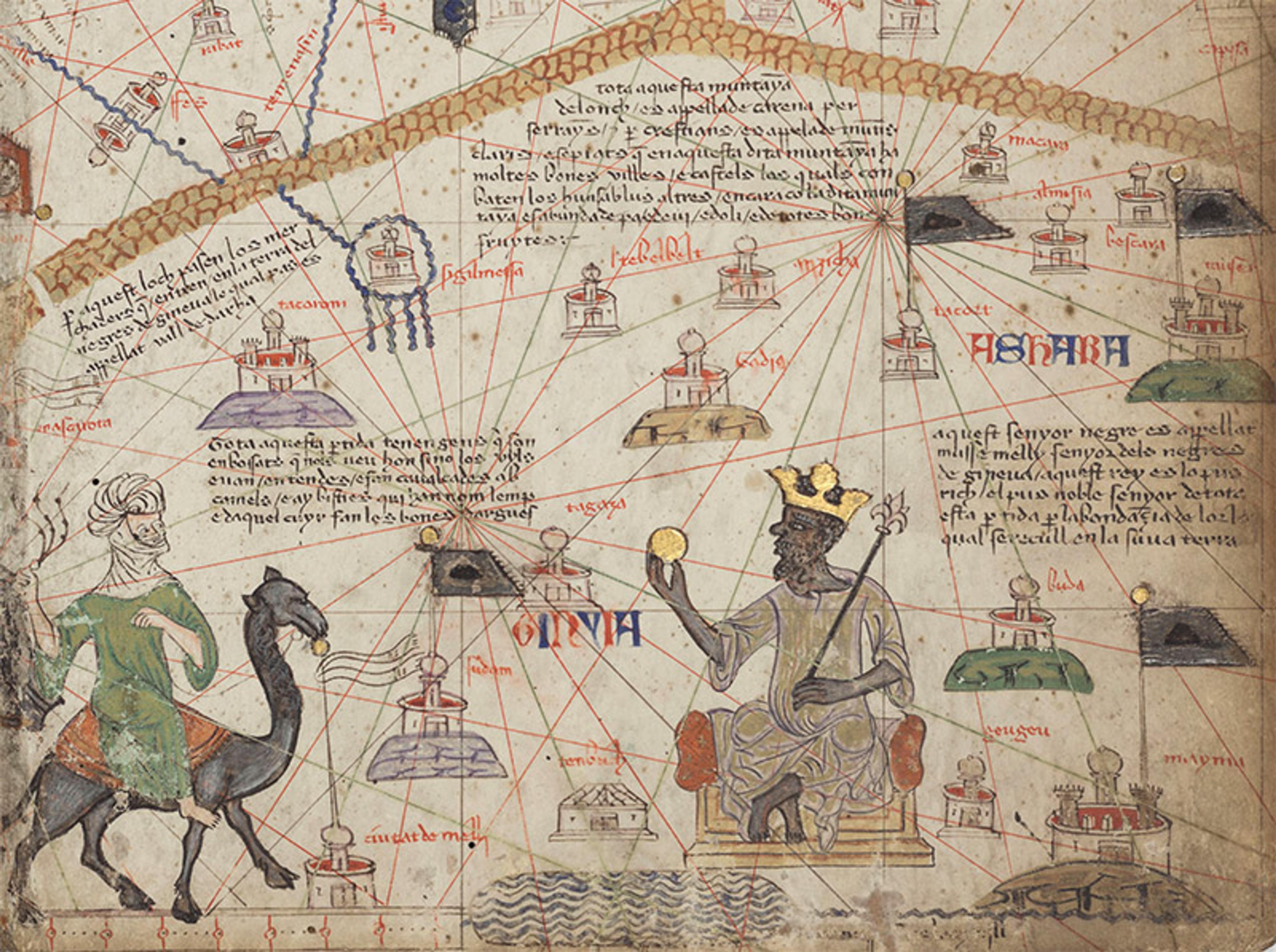

Mansa Musa, the ninth king of the Mali Empire, holding a golden orb or coin: from Sheet 6 of a Catalan Atlas (1375) detailing the Western Sahara. Courtesy the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

African history is replete with accounts of empires and kingdoms. By their nature, empires incorporate elements of colonisation in them. If this be granted, Africa must have had its fair share of colonisers and colonialists in its history. When, according to the mythohistory (the founding myth of the empire) of Mali, Sundiata gathered different nations, cultures, political leaders and others to form the empire in the mid-13th century, he did not first seek the consent of his subjects. It was in the aftermath of their being subdued by his superior force that he did what Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century insisted all rulers should do if their rule is to escape repeated challenges and last for an appreciable length of time: turn might into right. Ethiopia, another veritable empire, is a multinational, multilingual, multicultural state whose members were not willing parties to their original incorporation into the polity. Whether you think of the Oromo or the Somali, many of their successor states within Ethiopia are, as I write this, still conducting anticolonial struggles against the Ethiopian state.

Ọ̀yọ́ was an empire whose reaches, at its peak in the 17th and 18th centuries, extended from its capital in present-day Nigeria’s southwest as far west as present-day Togo, with complex systems of governance for the capital and for outlying areas. As an imperial formation, Ọ̀yọ́ was also a significant colonising power in West Africa. The Nigerian archaeologist Akinwumi Ogundiran maintains that Ẹdẹ-Ilé, another city in southwest Nigeria, was founded by Ọ̀yọ́ denizens as a frontier colony to secure the border of the empire against competing potentates who, significantly, were their non-Yorùbá neighbours. Additionally, there are other areas within Nigeria and in other parts of Africa where various forms of colonisation took place.

So it seems as if Africa is no different from other parts of the world where varieties of colonisation and imperialism flourished before the arrival of the modern version. The modern colonialism that came to Africa in the 19th century has since so dominated our imaginations that it has distorted how we see many aspects of history, including that of colonialism and empire themselves.

Let’s continue with how the idea of ‘precolonial Africa’ cannot but misdescribe the history of the continent. For instance, the Fanti banded together in the third quarter of the 19th century to give themselves a constitutional monarchy in a confederacy founded on a written charter. They did so not to counter British colonialism but to protect themselves from their old nemesis, Asante imperialism. Scholars continue to ignore the Fanti’s world-historical constitution, but that does not diminish its importance. The Fanti constitution attempted to improve governance with modern innovations; it placed science in the service of development and progress of their societies, including to advance urbanism and economics; and it created schools for girls. Their constitution shows Fanti societies were far from their description in much scholarship as simple, inward-directed, almost outside the movement of ideas and peoples in the world as it was then.

By the 19th century, coastal Ghana had been the location for several quite cosmopolitan communities. If you think there is some pristine ‘precolonial Africa’ before modern European imperialism, you are very unlikely to see this complex Ghanaian society for what it was: peopled by indigenous groups, Asians, North and South Americans, and Europeans speaking and interacting in numerous languages from which some Pidgin had emerged for purposes of commerce. These are elements that are unlikely to register with people for whom ‘precolonial Fanti society and identity’, to be genuine, must be static and uncontaminated in the aforementioned ways. This is yet another way the epithet limits thinking.

Similarly, 18th-century Fulani empire-builders adopted the language of the Hausa peoples whom they conquered; but, into the 21st century, the Fulani continue to hold sway in parts of northern Nigeria, and many who live there continue to view themselves as victims of Fulani colonisation. It was cooperation between Fulani and British arms and subterfuges in the early parts of the 20th century that helped to preserve their empire.

The ‘precolonial Africa’ epithet implies that we don’t take the history of Africa seriously

When we look past the ahistorical conceit of ‘precolonial Africa’ what we find is that, within the continent, clearly colonial hierarchies characterised relations between and among different African polities and peoples. So, the object that the term ‘precolonial Africa’ is used to describe – ie, ‘Africa before European colonisation’ – is full of colonisation that remains illegible to its proponents. This misdescription perpetuates the racist claim that Africa is the land that Time forgot. Regardless of how often we invoke the caveat ‘I am not trying to say that African phenomena are homogeneous or that things are the same everywhere, but we have enough likenesses among them to enable us to speak of them as being more convergent than divergent,’ the truth is that ‘precolonial Africa’ is nothing if not homogenising.

It renders invisible significant bodies of ideas that the world would do well to mind, if only we would deign to acquaint ourselves with them and rid ourselves of our colonial cathexes. For example, the long history of multination states such as Ọ̀yọ́ must be differentiated from small kingdoms like Ondo or even Ilé-Ifè. Ilé-Ifè enjoys the reputation as the spiritual homeland of Yorùbá peoples, and these polities contain many variations in modes of governance that have evolved over time. Should we speak of ‘precolonial Yorùbáland’? It’s self-evidently unhelpful. Given what we know of the change of the Ọ̀yọ́ state, over history, from its origins in prehistory through its shifting capital cities and ebbs and flows in its expanse, the reach of its authority, the changes in its types of governance, its diplomatic history, the civilisation it embodied and more, describing all of this as ‘precolonial’ will capture a mere sliver – the time it shared with modern, European colonialism – of its history beginning, effectively, in 1893.

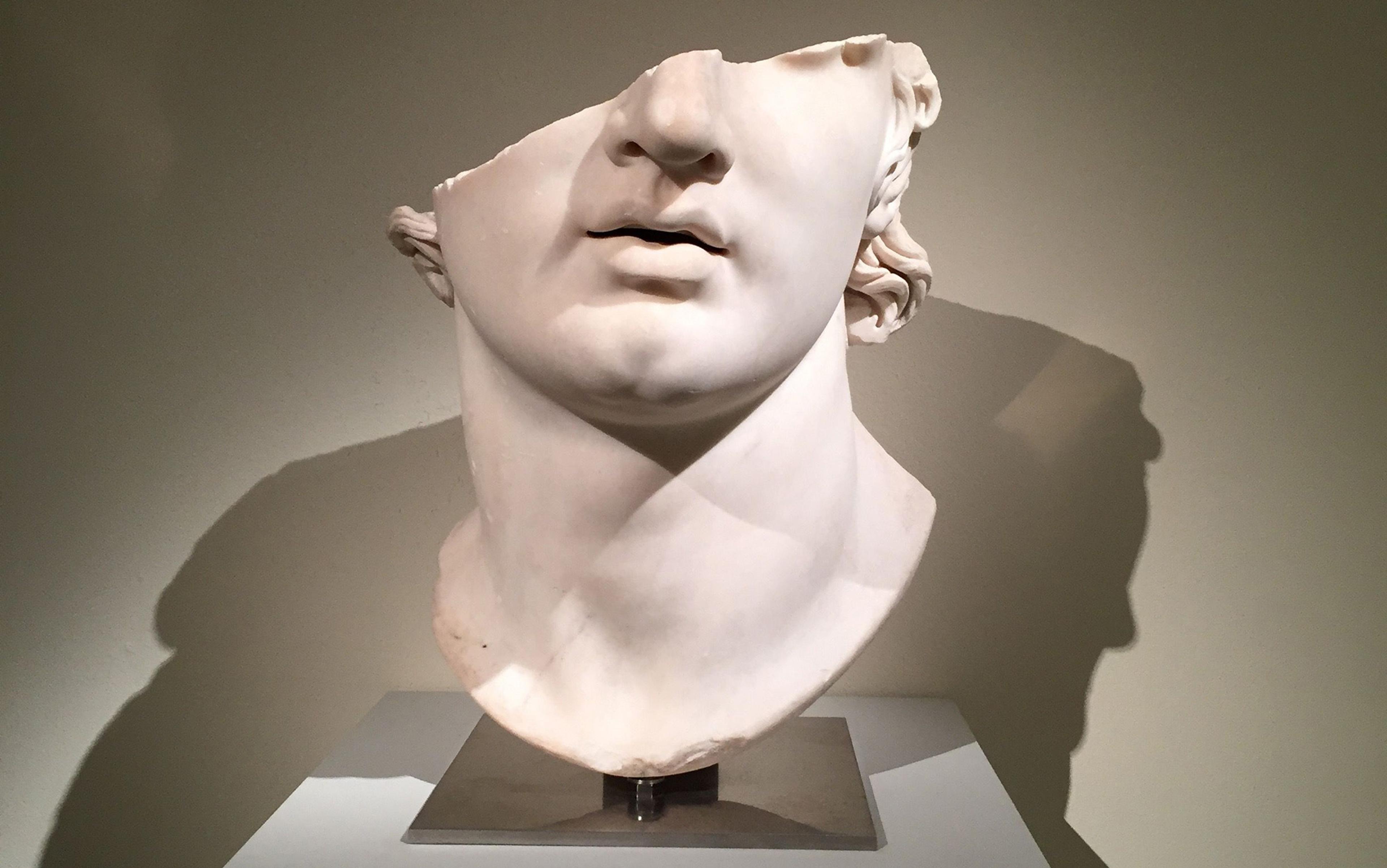

Yoruba shrine head (12th to 14th century), terracotta, Nigeria. Courtesy the Minneapolis Institute of Art

It is even more complicated. Ìbàdàn, a new city-state that came into being in its present state in the early 19th century, was – because its leading lights at the beginning were predominantly of Ọ̀yọ́ ethnicity within the Yorùbá nation – tenuously under the sway of the Ọ̀yọ́ Empire, itself in decline. To talk of ‘precolonial Ìbàdàn’, dating its history thereby by British colonial interference beginning in 1893, is to miss out the many ways in which it was a new kind of polity under a new mode of governance. Yes, Ìbàdàn’s chiefs were beholden to Ọ̀yọ́ and they appeared as if they were continuous with the monarchical system that dominated Ọ̀yọ́. Yet it was neither a monarchy nor did it mimic the grounds of political legitimacy that undergirded the Ọ̀yọ́ dynastic ruling class. Ignoring these novel emergences is part of what I mean by the poor quality of knowledge produced under the inspiration of the three-period analytical framework of history. There are no dynasties or ruling families in Ìbàdàn. This is just one example of the kind of complexity and change in political forms obscured by locutions such as ‘precolonial Yorùbáland’ or ‘precolonial Ìbàdàn’.

Perhaps the most damning aspect of the deployment of the ‘precolonial Africa’ epithet is its implication that we don’t take the history of Africa seriously. It tells the world that African history has only three periods – precolonial Africa, Africa under European colonial rule, and postcolonial Africa – that is, assuming we wish to entertain the idea of ‘postcolonial history’ given the debate in historiography and the philosophy of history regarding the legitimacy of the idea of ‘contemporary history’. As I have argued elsewhere, we African scholars must be the only ones whose people’s history has just three periods: one long precolonial period, which could be anywhere from the beginning of time to when colonialism, however construed, started; a short colonial period, which would leave Ethiopia, Egypt and Liberia out of its orbit; and the present postcolonial period. In the case of Liberia, for instance, it would mean only two periods, colonial and postcolonial, because its history is nowhere continuous with the histories of the autochthonous peoples who were displaced to establish it.

That this schema cannot be productive of serious history-writing, especially when it comes to our long past, seems to escape us. Because we do not invest in disciplines that will allow us serious access to knowledge of the past, expansively conceived – archaeology, geology, botany, palaeoanthropology, language and linguistics, religion and so on – we end up unwittingly presenting myths and legends as the stuff of our past, as if, as is the case elsewhere, we cannot derive deeper understanding from our material artefacts. We are unwittingly cooperating in our exclusion from history enacted by our enslavers and colonisers.

So the idea of ‘precolonial Africa’ is theoretically vacuous, limiting and, ultimately, obscures more than it illuminates. People are apt to forget a simple idea when they deal with African phenomena: theories do not follow geographical or cultural lines, and theories are never event- or culture-specific; they are better when they explain more phenomena with the fewest concepts, and, also, as long as they are applied to, in the present case, human-inflected actions, practices, processes and events. If they are good for such in Ọ̀yọ́, they must be good for similar ones in Siam. What theoretical framework is it that offers no clear boundaries for its referents, applies indiscriminately to empires as to non-state societies, to primitive social formations and sophisticated civilisations alike, without qualification? Only if we fail to pay attention to these substantial differences or think that, as is often the case, ‘it is Africa, after all’, can we evince no qualms about continuing to rely on this framework of understanding.

The rise and reign of the ‘precolonial Africa’ paradigm requires ignoring African intellectuals. We pay little attention to the works of African intellectuals before our time, especially those who fought the colonisers, who pioneered the tradition of writing history, offering analysis and criticism and explanatory models, and generally, telling African stories and history beyond oral traditions. Our stellar African intellectual forebears engaged in making sense of their respective societies’ place in the world. How did they do it? How, for instance, did they account for the evolution of their institutions, practices and processes through time, when they essayed to describe or explain such to themselves or to outsiders desirous of such knowledge, or even as preparatory to moving their societies along to better places? How did they accommodate Africa’s place in the global exchange of ideas and the movement of goods and peoples across the world’s boundaries from time immemorial?

Here is a good illustration. Ladipo Solanke (1886-1958) was a frontline anticolonialist intellectual and legal practitioner. He was a leader of the West African Students’ Union and was an ardent advocate of a self-governing West African federation, following the fashion of Australia and Canada, as a unit within the British Empire. As part of his efforts to educate the world, especially the anti-Black racists of his time who denied the humanity of Africans and insisted that Africa had not contributed anything to the march of civilisation, Solanke wrote the pamphlet United West Africa (or Africa) at the Bar of the Family of Nations (1927). Solanke presumed that West Africa was or could be a nation. This was an attitude shared by many West African intellectuals who insisted that, despite the traditions of particularism that marked the land, nations are not natural but historical creations. They thought that they, like Europeans or Americans, could forge a nation out of the plurality of ethnic groups to be found in their region. They had no quarter for the later substitution, brought to us by colonial anthropology, of the idea of ‘tribe’ and the associated idea of ‘tribalism’ as the natural unit of African peoples and societies.

Solanke’s periodisation for African history is especially relevant. It covers the four chapters of his pamphlet, viz:

Chapter 1 – West Africa in Ancient Times

Chapter 2 – West Africa in Medieval Times

Chapter 3 – West Africa in Modern Times

Chapter 4 – West Africa’s three ‘Rs’, namely Restoration, Regeneration and Rise; alias West Africa in Future

In contrast with the distortions wrought by the ‘precolonial Africa’ epithet, including its silencing of the history of Africa, Solanke was well aware that Africa had a long history. He knew that Egypt as well as Carthage were part of the history of Africa, and that they were colonial powers. Solanke was able to think more clearly about African history than many of our contemporary intellectuals. In the beginning of Chapter 1, on ‘government’, taking a comparative approach to his subject matter, he reminded his readers that ‘there is yet very little to say about West Africa’ during ancient times ‘by way of written evidence’. He quickly added that the region was no different from ‘all other nations past and present’ that ‘also have very little to say about themselves at this same period’. He went on to claim that ancient Egyptian civilisation had global influence in the then world and ‘ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, the Abyssinians, and the Carthaginians’ all had ‘close contact with West Africa through trade several centuries before Christ’. But this did not mean that attainments by West Africans in ‘governments, education, trade, industry and religion’ could be attributed to foreigners, or that there is any discontinuity between what obtains in the region in the modern era and their antecedents from antiquity.

Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Sirte predate European colonialism by centuries

In the preceding section, Solanke places Africa in the general course of world history. He conveys his interest in the specific place of West Africa and in particular states and societies therein, both in terms of their individual histories and their connections with other parts of the world. Notably, Solanke does not use colonialism as the axis of periodisation. For that reason, there is no need to turn the centuries or aeons into some nebulous ‘precolonial period’, homogenising distinctive historical periods and societies as whatever they were relative to colonialism. The term represents an embarrassingly shallow privileging of modern European colonialism in the sweep of African history.

We would benefit from remembering the Nigerian historian J F Ade Ajayi’s corrective that colonialism is an episode in African history, not its principal, much less sole, shaper. Take any of Africa’s native civilisations. We have evidence for Yorùbá civilisation going back 1,000 years at least. Benin history also goes back at least 1,000 years. Then, in 1897, the Bini lost a war to the British and came, as war booty, under British control, and not even as a colony or a protectorate. All of a sudden, Benin’s whole history – with its dynastic calendar, its imperial records and reaches, including control of Europeans within its borders for centuries till that fateful incident – was subsumed under ‘precolonial Benin’. Thenceforth, Benin was to be understood primarily, if not solely, in terms of its relation to one European conqueror. All that came before 1897 is now ‘precolonial Benin’.

Ironically, this dominant organising principle of African history hinders our understanding even of European colonialism in Africa. It encourages us to ignore the many important continuities in African phenomena. It asks us to neglect why and how some African groups welcomed European intervention and embraced modern forms of rule, in part, as their escape from local colonial overlords or from certain ways of ordering life and thought in their original cultures. We paper over many long-standing hierarchies among groups and the dynamics of intergroup relations that had previously structured ideas of citizenship, political legitimacy, succession systems, even geopolitical boundaries, and we wonder why the limited toolkit bequeathed by scholarship that takes colonialism as its singular pole for periodisation does not avail in our contemporary situation. We saw previously that, in coming together to give themselves a new constitution, the Fanti were trying to ally with the British and against the Dutch as well as their local threat, the much bigger and stronger Asante kingdom. Many women utilised the new private laws birthed by colonialism to breach local regulations respecting marriage, child custody, and inheritance rules.

Organising the history of Africa in relation to European colonialism also conceals local versions of colonial state relations and the different models of citizenship in Africa’s long history of states, nations and constitutions. Many of these models need a more sophisticated calendar and dating system to lead us to their relevance and complexities. Ethiopia, for example, has always been an agglomeration of once-independent states under Amharic hegemony. But to speak of ‘precolonial Ethiopia’ would be to commit to something that never happened. Unlike Ethiopia’s colonisation of Eritrea and Somalia, which lasted far longer, Italy’s so-called colonisation of Ethiopia barely lasted five years! How then do we conceive of Ethiopian history such that we grasp its evolution as a multination state, some of whose internal strains and stresses owe to the dynamics of local colonisation when it comes to ‘Western Somalia’ (previously Ogaden), Eritrea (now independent), or Oromia? After all, two of these and other components are constituent units of present-day Ethiopia.

Or to take another example, how do we make sense of the fact that the repeated threat to the corporate integrity of the Libyan state cannot be understood or named in terms of Italian colonialism? It can be traced, instead, to happenings as far back as biblical times and the continuing concatenations of peoples and regions in the country. Tripolitania, Cyrenaica and Sirte predate European colonialism by centuries. Competition among them represents continuities that our current fixation on European shenanigans cannot begin to unravel.

Egypt from the 16th to the 18th centuries was a satrapy of the Ottoman Empire before the genius of Mohammed Ali in the 19th century turned it into a local coloniser, if not imperial power, dominating regions to the north, in the Mediterranean and southern Europe, and to the south, especially Sudan. All of the Iberian Peninsula and huge portions of southern Europe including huge swaths of France and Italy were, at some points in the past, colonies of African potentates. Do we speak of precolonial Spain? Would anyone organise all of Spanish history in terms of its colonisation by the Moors, or of Malta and portions of Italy earlier by Carthage and later by Syria and Arabia by Egypt under Ali? Spain does not deign to deny its Moor-inflected past – it has monetised it in the tourism industry – even as there are ongoing debates about its place in its history. Meanwhile, Moorish rule lasted longer there than British rule lasted in any part of Africa.

Perhaps the most pernicious effect of deploying the various iterations of ‘precolonial’ is the way it marginalises ideas, especially philosophy, in Africa. Because ‘precolonial’ takes colonialism as the dividing line for organising ideas within its temporality and forces us to conceive of spaces relative to how they stand in the arrival and dispersal of colonialism in the continent, we, unwittingly for the most part, end up talking as if ideas, practices, processes and institutions can be understood within frameworks delineated by the precolonial, colonial and postcolonial schema. So, when we are looking at philosophy or modes of governance – to take two arbitrary examples – given our justifiable hostility to things colonial, we construe ‘precolonial’ as necessarily having nothing to do with the colonial, the latter understood as having ‘European’, ‘Western’ or ‘modern’ provenance while, simultaneously, interpreting it as ‘traditional’, ‘indigenous’ and the like.

The misdescription we identified above induces misinterpretation as well as a misrecognition of the genealogy and exchange of ideas, the evolution of institutions, and the identity of thinkers in the area. The problem is profound. Because of the primacy accorded to identity in the business of finding ideas and institutions that could be separated from anything European, Western or modern, African scholars for a long time contorted themselves into finding ‘African philosophy’ that was authentically ‘African’, were even willing to give up on the very term ‘philosophy’ and called their ideational production ‘African Traditional Thought’. The driving question was a matter of whether or not such ideas had been ‘contaminated’ by colonialism and its appurtenant practices, ideas, processes and institutions. When a scholar announces an interest in studying ‘Traditional African Political Thought’, in light of our analysis so far, the first question to ask is whether ‘traditional’ in this formulation has any room for evolution such that we can periodise ‘traditional thought’. Of course, I am assuming what should be obvious: is the thought involved the same throughout history, or were there changes induced by both exogenous and endogenous causes to it, and how are those changes to be understood? The other problem takes us to the next section of this discussion: the problem of facilely deploying an entire continent as a unit of analysis.

Let us recall the temporal framework adopted by Solanke above. Anyone reading his account is immediately enabled to situate his ideas about what transpired in medieval West Africa in relation to what was happening at other places in Africa, nay, the world, within the same temporal boundaries. This enables us to see how similar ideas found in different parts of our world do not have to be explained in terms of influences or common origins. That way, we would have no difficulty identifying African contributions to the global circuit of ideas in ancient times, in medieval times and right to the present. And such contributions would not be limited to so-called ‘authentic’, ‘indigenous’ or ‘traditional’ African fare. The tendency to treat Africa as a unit of analysis motivated by a wrong-headed approach, which took challenging Europe’s ignorant elucidations of African phenomena as the primary object, has issued in genealogies and narratives of intellectual history that bear no resemblance to how things really happened in history, or how African thinkers actually conducted themselves in the global circuit of ideas. This is why Africa hardly ever features in the annals of philosophy, and chronologies in philosophy anthologies do not carry African entries in frameworks demarcated by the Gregorian calendar.

We offer more to the world and ourselves than exotica and garnishes for their discourses

Historically, from Egypt to the rest of the Mediterranean continuum and beyond, to areas of southern Europe and what used to be called Asia Minor, Africa, Africans and their ideas and intellectual work were neither a mute nor a subordinate presence in philosophy and the history of ideas. From ancient times till the 19th century when modern European colonialism began to hold sway, Africans have without interruption been philosophers. The history of philosophy must be made to take account of African participation in medieval philosophy – Christian, Islamic or secular, it does not matter – as well as theology, mathematics, astronomy, etc. African-derived Roman senators or poet laureates are no less African for having become Roman notables, just as Alexander the Great does not become any less Mediterranean for having had his legacy domesticated in medieval Mali. The origins of the monastic tradition in the Catholic Church did not owe only their physical location to the deserts of present-day Algeria. Maimonides was no less an African presence for his Jewishness. And we certainly do not wish to obscure the role that African minds – for example, Saint Augustine and Saint Anthony – have played in the development of Catholic philosophy and theology.

It is fair to ask: what about ideas and practices that could not be immediately traced to the literate cultures that I have so far referenced? I do not see any problem here, either. Again, the key is in distancing ourselves from references like ‘precolonial’ or ‘traditional’ in identifying African phenomena. We should take seriously the fact that every political arrangement with a modicum of complexity and sophistication is a response to one of the central questions of political philosophy – who ought to rule when not all can rule? With this foundational question in mind, it becomes easier to look at African modes of governance for the answers they offer. The fact that their founding principles were not written does not make them any less complex or without a discernible history. The challenge for scholars is to begin to address African life and history and ideas in relation to those principles. When we have identified those principles, we should, as is done for other philosophical traditions, explore them for coherence, cogency and normativity. For example, the problem of the obligation to obey political authorities is no less present in the Ọ̀yọ́ monarchical state while it was supreme than in the United Kingdom of the 17th century to which Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan was one response. What was the basis of the legitimacy of the rulers back then? Once we settle on this way of studying our philosophical heritage, the road is open to tracking how our institutions, practices and processes have evolved over time, by what or whom they have been influenced, and so on.

Ọ̀yọ́ is one of the longest-lasting states in West Africa. It enjoyed at least 1,000 years of recorded history, from 1000 CE till now. Ọ̀yọ́ governance was monarchical with a hierarchy of lower chiefs and other functionaries. It did not start out as an empire, a polity that conquers and rules others, we know that for a fact. We then need to know on what principles the legitimacy of the king’s rule was based. Yes, heredity was central, but we also know that, while it lasted as an imperial power, the Crown Prince was mandated to die with his father whenever the latter passed on as king.

Here is an unusual constitutional arrangement redolent with possibilities for different kinds of philosophical analysis. When was this rule regarding the Crown Prince introduced? We know it ended around 1859. We might obtain some insights into the place of heterodoxies among Ọ̀yọ́ thinkers and other intellectual types by exploring why and whether there were external influences, for instance, from immediate neighbours and Islam when it was introduced into the capital of the realm, in the very constitution of the system originally, and in its variation, over time. We can do the same for so-called stateless communities. After all, many such communities evolved modes of governance that enabled them to allocate public goods, keep social conflicts in check, ensure the safety of life and limbs and possessions, if not property, and so on. Lumping them all in some precolonial mist is not analysis; it is anti-intellectual abdication. Dispensing with this organising device will make for a vast expansion of the fields of enquiry, and for new research in African history under frameworks from archaeology to palaeoanthropology, art history to musicology, history to religion. We offer more to the world and ourselves than exotica and garnishes for their discourses.

To date, the works of individual thinkers, their respective places in the annals of thought across the globe and their contributions to the perennial questions of philosophy in their own domains have not been part of Africa’s intellectual history and philosophy. Because we are working within the Gregorian calendar that most of the world now follows, we are able to zero in, as a matter of historical specificity, on particular thinkers in particular periods, working on their own or being parts of discursive communities not limited to their own vicinities. Thus, we end up with more robust and more adequate renderings of the historicity of African ideas and thinkers in Africa and their place in the world. Eighteenth-century philosophy can open up beyond Königsberg to Timbuktu. Nineteenth-century philosophy can take seriously the exertions of James Africanus Beale Horton, Rif’ā’ah al-Ṭahṭāwī and Fukuzawa Yukichi – in Sierra Leone, Egypt and Japan, respectively – in their engagement with modernity and what it meant for their respective societies. Horton wanted Africans to embrace modernity, and both al-Ṭahṭāwī and Yukichi are regarded as the principal proponents of modernity in their respective locations in the 19th century.

All this would be invisible to the trinity of precolonial, colonial and postcolonial division of African history for organising states and ideas, practices and institutions, processes and thinkers and intellectual movements through time. Tossing the retrograde ‘precolonial’ epithet in the dustbin can bring only gains in expanding our knowledge, enriching our conceptual repertoires, and telling stories that are closer to the truth than the alternative.

It is time to say bye-bye to the idea of a ‘precolonial’ anything in our intellectual discourses respecting Africa.