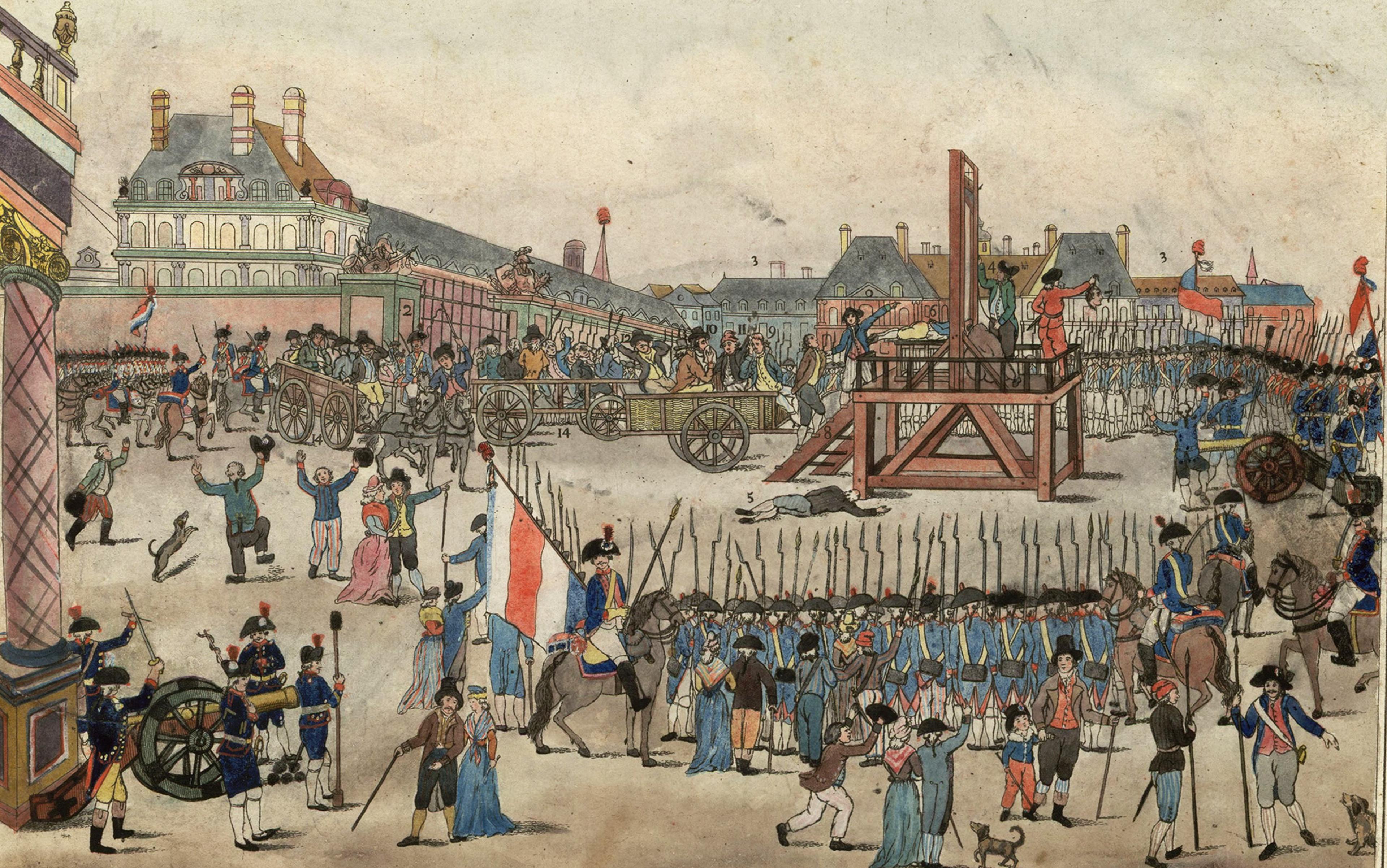

After declaring independence from France on 1 January 1804, Haiti became the first state anywhere to permanently outlaw slavery and ban imperial rule. By establishing a land of freedom in a world of slavery, Haiti’s founders – the generals Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Henry Christophe and Alexandre Pétion – challenged the contradictions of the western European Enlightenment, whose proponents had pronounced liberty and equality to be only for white men. ‘I have avenged America,’ proclaimed Dessalines, independent Haiti’s first leader.

To this day, Haitian independence remains the most significant development in the history of modern democracy. The theories undergirding it – that no human beings could ever be enslaved – continue to define contemporary political ideas about what it means to be free.

Despite the Haitian Revolution, much of the credit for the eventual destruction of the transatlantic slave trade and the elimination of Atlantic slavery has gone to French and British abolitionists. The Trinidadian historian Eric Williams complained about this in his groundbreaking book Capitalism and Slavery (1944) when he wrote of the abolitionists: ‘their importance has been seriously misunderstood and grossly exaggerated by men who have sacrificed scholarship to sentimentality and, like the scholastics of old, placed faith before reason and evidence’. Many historians have likewise chosen to forget that Haiti’s fight to end slavery in the Americas didn’t cease when the Haitian revolutionaries declared victory over France.

The 19th-century French anti-slavery humanitarian and historian Victor Schoelcher diminished the importance of the Haitian Revolution when he suggested that the Haitian people didn’t use their newfound freedom to help end slavery elsewhere in the Americas. ‘Is it not a shame,’ he admonished, ‘that you have not taken any part in the efforts of Europe for emancipation, that you have not even sent any statement of solidarity or sympathy to the friends of emancipation, and that in this republic of emancipated slaves, there is not even a society of abolition?’ But Haitians did directly interfere with the inner workings of slavery: both discursively, by circulating anti-slavery pamphlets, and materially, by disrupting a key node in the international slave trade – the Middle Passage.

After Dessalines was assassinated in October 1806, Haiti was split into two, with Pétion ruling in the south and Christophe ruling in the north. Even though both states of Haiti had laws declaring that they wouldn’t interfere in the ‘business of other countries’, Pétion provided amnesty, weapons and ammunition to the Venezuelan freedom-fighter Simón Bolívar, who subsequently defeated Spanish rule to create the independent state of Gran Colombia; and both Haitian governments, but especially Christophe’s – who would crown himself king of northern Haiti in 1811 – contributed to anti-slavery struggles by seizing slaving vessels and liberating their captives.

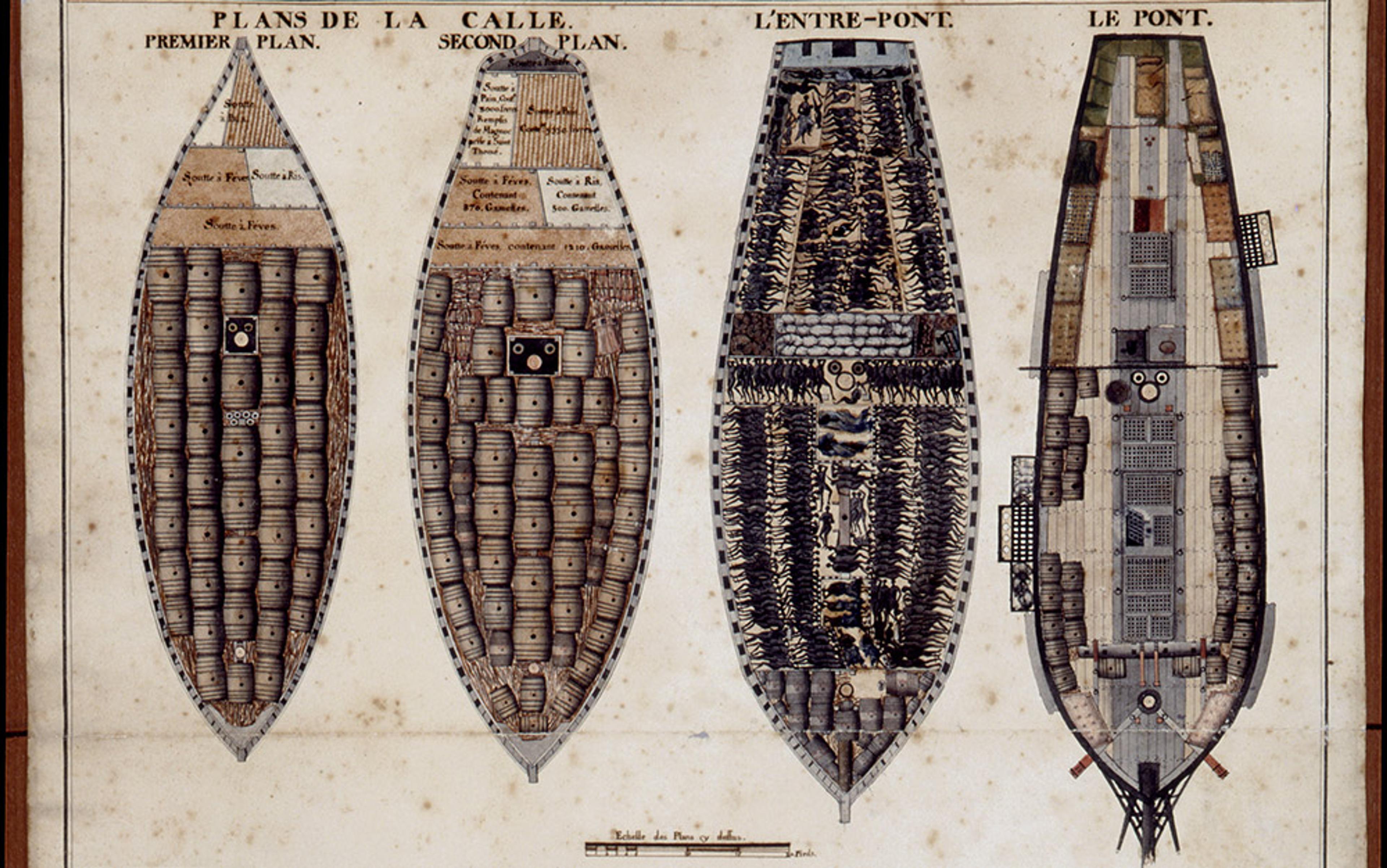

The most renowned of these liberation operations occurred in October 1817. The Royal Gazette of Hayti reported that Haitian authorities had captured a Portuguese frigate near the northern city of Cap-Henry. The ship was on its way from Cape Verde, off west Africa, to Havana when officials from the Kingdom of Hayti took control of it and set free 145 Africans, ‘victims of … the odious traffic in human flesh’. The captives were in ‘an awful state’: many had already perished, and the survivors ‘looked like ghosts ready to die of misery and starvation’. Once ashore in Haiti, they were greeted by a crowd who assured them that ‘they were free and among brothers and compatriots’.

Seven years earlier, the northern Haitian military had captured a different Portuguese slaver carrying two Hausa-speaking children. These so-called ‘nouveaux haytiens’ were as stunned to hear their native language as they were surprised to find some of their ‘former countrymen’ already living in Haiti: ‘It was as if they were meeting once again the parents from whom they had been ripped away.’ Such operations had by that time become common. The northern military intervened to stop the slave trade again on 2 February 1811 when they captured a Spanish ship, the Santa Ana, and liberated 205 Africans shackled in the hold.

Out of revenge, Spanish and Portuguese slavers began to attack Haitian merchant ships and engage in raids on Haitian beaches, seizing men, women and children to sell into slavery. In 1812, a Spanish schooner captured the Haitian brig Poule d’Or, and sold its captain, Azor Michel, and two children on board in Cuba. Azor and the children were returned only after Christophe intervened to request ‘the return of all Haitian subjects who are or may still be detained in Cuba’.

The existence of freedom and independence on the island of Haiti terrified planters and heads of slavery throughout the Atlantic World, including the US president Thomas Jefferson who subsequently punished both states of Haiti by issuing trade embargoes. But Christophe’s success in forcing the return of captive Haitian citizens shows that, despite the precarious position of his Kingdom of Hayti, this monarch was not a powerless figurehead who could simply be pushed around by the colonial powers.

After two centuries of bad press, confronting these accusations against Haitian leaders is important

King Henry, however, wasn’t always recognised as having used his powers for good. Although he was something of a hero during his lifetime to British abolitionists such as Thomas Clarkson and William Wilberforce, soon after his death in 1820, it would be Christophe himself who would be accused of effectively re-enslaving the Haitian people.

Henry Christophe, King of Haiti (1816) by Richard Evans. Public domain

In The Present State of Hayti (1828), James Franklin, a British traveller who had lived under King Henry, wrote that Christophe forced his people ‘to perform that labour which ought to have been performed by brutes’. In 1842, the British Quaker John Candler accused Christophe of having ‘compelled’ ‘bands of men and women … to labour under insufficient rations of food’, causing ‘vast numbers’ of them to die. These were grave charges to heave at the late king.

After two centuries of such bad press – whereby Haitian leaders have been charged with ‘national incompetence’, and the populace has been described as at once ‘progress-resistant’ and of having ‘deep in [their] psyche … a violence that goes beyond all violence’ – confronting these accusations is an important challenge.

As a Haitian American, I feel a responsibility to treat this history right, especially when such damning recitations of Christophe’s rule have been repeated across the Americas. In The Kingdom of This World (1949), the Cuban novelist Alejo Carpentier, combining elements of marvellous realism with apocryphal legend, paints Christophe as ‘a monarch of incredible exploits’ who everyday ordered ‘several bulls’ to have ‘their throats cut so that their blood could be added to the mortar to make [his] fortress impregnable’.

Christophe’s story, recorded in histories and plays, poetry and novels, and in journalistic accounts, by his friends and his foes, is filled with enough legends and fables, ambiguities and silences, triumphs and failures to preclude anyone from claiming to set down a definitive version. In fact, the Citadelle erected in 1813 to protect the kingdom from foreign invasion – today a UNESCO World Heritage site – unwittingly symbolises the numerous interpretations available to those who seek to probe Christophe’s life. In the words of the St Lucian poet Derek Walcott, King Henry’s fortress marks ‘the slave’s emergence from bondage’ at the same time as it suggests that ‘the slave had surrendered one Egyptian darkness for another’.

Citadelle Laferrière in Haiti. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

Yet France’s aggression against its lost colony proves that its leaders were far more pharaoh-like than Christophe. In the early 19th century, Napoleon was overthrown twice and, both times, Louis XVIII – who was restored as French king in 1814 and 1815, respectively – following the urges of the former colonists, attempted to ‘reconquer Saint-Domingue’ (as the French called Haiti) and bring back slavery. Indeed, throughout the 19th century, Haiti faced consistent existential threats to its sovereignty from the US too. What almost all previous attempts to write about the vexing reign of Christophe have lacked is recognition that the Haitian king was attempting to create a free and prosperous country in a world hostile to the very existence of people who looked like him.

Historians disagree about Christophe’s origins. Three men who had been, at various times, in his inner circle – Hugh Cathcart, a British agent at Port-Républicain; Colonel Vincent, a French military officer; and Baron de Vastey, secretary to the king – report that Christophe was born on 6 October 1767 on the British island of Grenada. Vastey’s Essay on the Causes of the Revolution and Civil Wars of Hayti (1819) is the most significant account: the only one we know Christophe read and sanctioned.

According to Vastey, Christophe, aged 12, fought in the Battle of Savannah during the American revolutionary war with the French Chasseurs Volontaires, a regiment of French troops of colour from the colonies. By the time widescale slave rebellion broke out in Saint-Domingue in August 1791, Christophe was back in the colony, employed at the Hôtel de la Couronne on rue Espagnole in Cap-Français.

The Jacobins abolished slavery in the French empire in 1794. However, by 1799, Napoleon was determined to restore it as he assumed control over France. When he sent his brother-in-law Charles Leclerc to Saint-Domingue with 20-40,000 French troops in late January 1802, he found brigadier-general Christophe, commander over the city of Le Cap, stern, stoic and inflexible. Christophe eventually had the city burned to the ground in order to prevent French occupation. But in April 1802, convinced by Leclerc that the French had no intention of reinstating slavery, Christophe defected to their side, which would lead to the demise of the great revolutionary general Toussaint Louverture. Soon after, Louverture was arrested and deported to France where he would die in prison.

The Kingdom of Hayti had a beautiful palace that rivalled the most opulent structures in old Europe

After news reached Saint-Domingue that Napoleon had reinstated slavery in Guadeloupe, Christophe became a key member of the indigenous army that would eventually free Haiti. Wary of the fact that Christophe had previously joined the French side, rival general Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci refused to accept Christophe’s re-integration. In retaliation, Christophe had him executed. This execution has clouded Christophe’s legacy – even if, relatively speaking, it was hardly discussed in a world already suppressing the significance of enslaved people overthrowing their masters.

Despite such disastrous internecine struggles, under the leadership of Dessalines, on 18 November 1803, the indigenous Haitian army defeated French troops at the Battle of Vertières and declared Haiti independent. Given command over the entire military by Dessalines, who had made himself emperor, Christophe later found himself accused by Pétion of contributing to the plot by which Dessalines was killed. Christophe, in turn, charged Pétion with orchestrating the assassination. These conflicts led to the 13-year civil war in Haiti that would be extinguished only once both Christophe and Pétion were dead.

By 1813, the Kingdom of Hayti under Christophe had an entire system of nobility, with hundreds of dukes, counts, barons and chevaliers, as well as a beautiful palace, richly adorned with complex architectural details that rivalled the most opulent structures in old Europe. The construction of this palace, called Sans-Souci – some say in lugubrious recognition of the man Christophe had killed, others say after Frederick the Great’s summer chateau in Germany – led to the charges that, although he proudly proclaimed himself to be the ‘first monarch crowned in the New World’, the Haitian king had merely brought to it old-world despotism.

Coloured print of Sans-Souci Palace in 1822. From: Henry Christophe, King of Haiti. Courtesy the FCO Historical Collection FOL. F1924/Kings College, London

By 1820, after Christophe’s suicide, the Kingdom of Hayti was no more. In 1833, the US traveller Jonathan Brown visited Haiti, and criticised the late monarch in The History and Present Condition of St Domingo (1837): ‘With the despotic power and a portion of the prospective ambition of the ancient Egyptian kings, Christophe employed vast multitudes of his subjects, gathered from every district of his kingdom, to accomplish the stupendous undertaking which he had planned.’ Claiming to have based his claims on firsthand testimonies, Brown continued: ‘When measures of public necessity or public embellishment required it, the whole labouring population of a district was called out en masse, and made to continue their toil until the work was finished.’

Writing in the 1840s, the Haitian historian Thomas Madiou also described Christophe as having mandated ‘forced labour’ when he ordered that farm workers be ‘attached to the glebe’, meaning that they couldn’t leave the habitations where they were employed. Furthermore, Madiou wrote: ‘The proceeds of this forced labour were used largely to cover the expenses of his government. Property owners were no longer the masters of their income; tax officials seized [their revenues] to fill government coffers.’

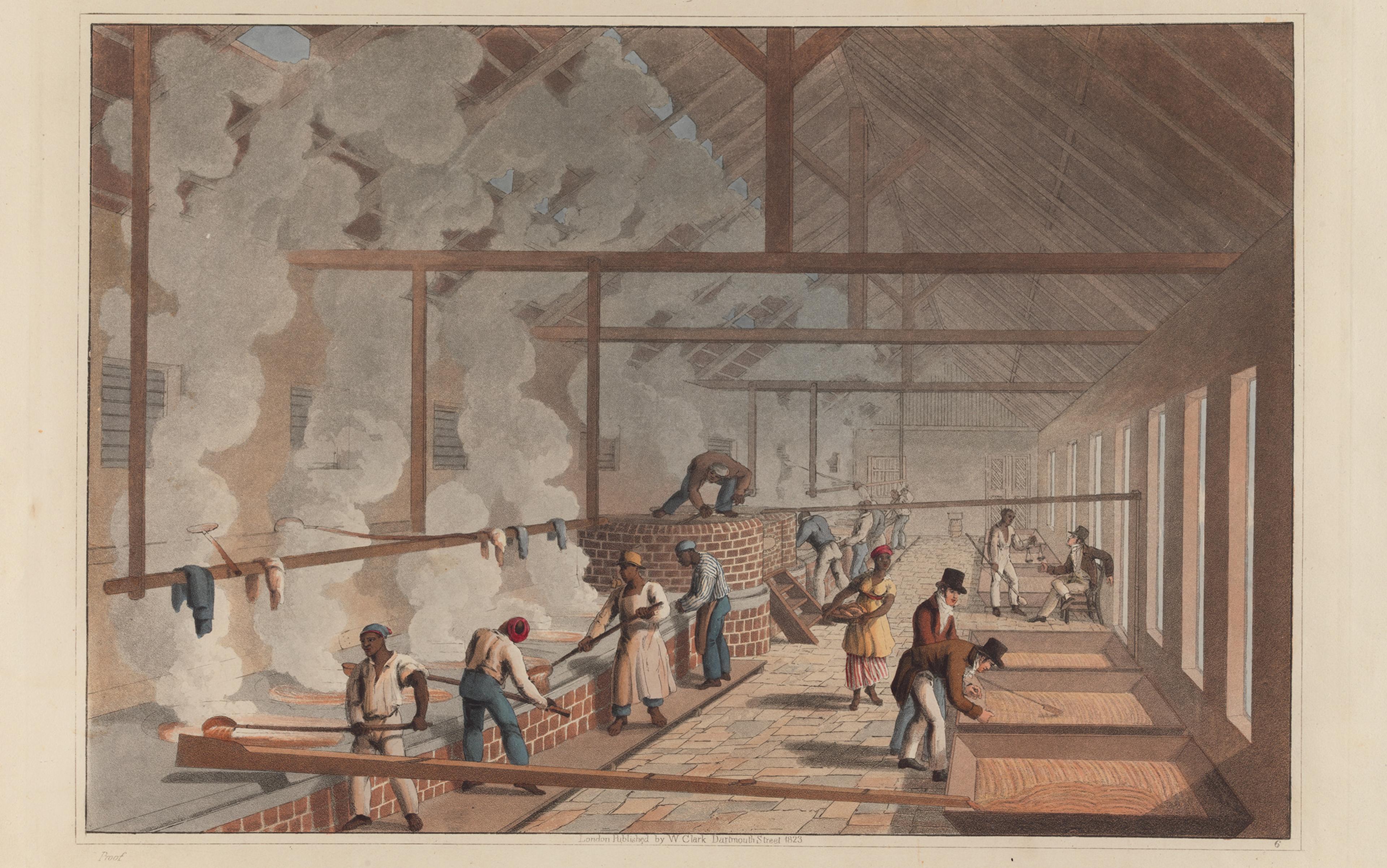

In 1812, Christophe had issued a complex series of labour laws called the Code Henry. Yet even with its titular echo of both Louis XIV and Napoleon’s draconian Code Noir and Code Napoléon, respectively, foreigners recognised Christophe’s Code not as a blueprint for a form of forced labour that was simply slavery by another name, but as the greatest work of legislation governing the rights and duties of workers that the world had ever seen: ‘In lieu of wages,’ the third article states, ‘the labourers in plantations shall be allowed a full fourth of the gross product, free from all duties.’ The Code thus described an elaborate system of compensation that much more closely resembled a paternalistic cross between share-cropping and feudalism than chattel slavery.

The British naturalist Joseph Banks wrote: ‘It is without doubt in its theory … the most moral association of men in existence; nothing that white men have been able to arrange is equal to it.’ Banks explained that these codes could prevent worker alienation:

To give the labouring poor of the country a vested interest in the crops they raise, instead of leaving their reward to be calculated by the caprice of the interested proprietor, is a law worthy to be written in letters of gold, as it secures comfort and a proper portion of happiness to those whose lot in the hands of white men endures by far the largest portion of misery.

Banks hoped that Christophe’s Code could help ‘conquer all difficulties, and bring together the black and white varieties of mankind under the ties of mutual and reciprocal equality and brotherhood’.

The French anti-slavery historian Antoine Métral echoed the admiration. He referred to Henry’s laws as ‘original beauties’, and the Black American abolitionist Prince Saunders was so enamoured that he had portions of the Code printed in English translation in his Haytian Papers (1816), before relocating to northern Haiti to start a school in Port-de-Paix. Saunders became acquainted with Christophe through Wilberforce, who sent him to Haiti to distribute the smallpox vaccine.

The aim was ‘for every Haytian … to have the ability to become the owner of the lands of our former oppressors’

Christophe was in regular contact with Thomas Clarkson, too. On 5 February 1816, Christophe explained to the renowned abolitionist his plan to institute a public school system:

For a long while, my intention, my dearest ambition, has been to secure for the nation which has confided to me its destiny the benefit of public instruction … I am completely devoted to this project. The edifices necessary for the institutions of public instruction in the cities and in the country are under construction.

To facilitate national education, Christophe created a programme to sponsor foreign artists, scientists, musicians and mathematicians, as well as English teachers, to come to instruct Haitian students, both boys and girls. He set up a Royal Chamber of Public Instruction, appointed a minister of education, and issued an edict mandating that schools would be developed throughout northern Haiti.

While exports – indigo, cotton, sugar and tobacco – of the kingdom’s staples were strong, Christophe also urged Haitians to cultivate wheat and other grains. The goal was to make his country less dependent upon foreign imports. He also created a programme whereby any Haitian could apply to acquire the erstwhile farms of the French planters. The aim was ‘for every Haytian, indiscriminately, the poor as well as the rich, to have the ability to become the owner of the lands of our former oppressors’.

Some of the world’s most storied anti-slavery advocates admired the Kingdom of Hayti, but many of northern Haiti’s foreign inhabitants questioned whether the king’s codes benefited the average Haitian citizen. William Wilson, a British teacher who worked in Cap-Henry, wrote to Clarkson shortly after Christophe’s death: ‘They owed him all that they had. As the founder of their most beneficial institutions, he had done everything for them.’ Yet, ‘If he made good laws, he was the first to violate them,’ Wilson explained. ‘In a word, he was a philosopher.’ A rival journalist from the southern republic, Hérard Dumesle, also claimed that, though the Code described the plan for a remarkably novel society, it was one that ‘only existed on paper’.

In March 1818, the Gazette announced that: ‘All the idle people in the towns and villages have been rounded up and sent to the countryside to engage in the work of farming.’ The Haitian people were assured that preventing ‘idleness’ was merely proof that ‘our august and beloved Sovereign is taking every care to ensure the prosperity of agriculture and commerce’. Some of Christophe’s foreign supporters claimed this harsh hand of ‘kingly power’, as the US journalist Caleb Cushing wrote, had been needed to preserve Haiti’s freedom from slavery and independence from colonial rule in a world determined to see the descendants of Africans fail.

Madiou disputed the claim that instituting feudalism could secure Black freedom. According to him, workers on northern farms received almost no compensation and the farmers themselves, because they had to pay such high taxes to the state, could keep only a quarter of their revenue. For Madiou, this was not the kind of liberty and equality promised by the Caribbean’s first and only modern king, one who had sworn at his coronation ‘to never allow, under any pretext, the return of Slavery nor of any feudal system contrary to liberty and the exercise of the civil and political rights of the people of Haiti’.

In the early 19th century, Haiti was the only example in the Americas of a nation populated primarily by former enslaved Africans who had become free and independent. Other nations, including Haiti’s trading partners, were determined to prevent abolition and their colonies from becoming free, so they refused to recognise Haitian sovereignty. When France finally agreed to do so in 1825, it extracted the astounding price of 150 million francs from Haiti for the act. To preserve slavery in its territories, England didn’t officially recognise Haitian independence until 1838, five years after it abolished slavery. The US refused recognition until after the start of the American Civil War, when most of the southern states had seceded from the Union. Even in the so-called Age of Revolutions, Black freedom in the Americas was not only feared, but reviled.

Understanding the kind of state Christophe tried to create means understanding that the world he lived in was one where the liberty of Black people was everywhere under threat. To deny that diplomatic nonrecognition, the return of slavery and the threat of foreign occupation made governing Haiti complicated is to contest the very force and power of slavery and colonialism. The spectre of Black freedom and self-government in the Americas was so frightening that its realisation brought punishment to Haiti again and again. At the same time, the insidiousness of Atlantic World slave economies was so great that, even though he never did reinstate slavery, the king of Hayti still profited from the institution. Indeed, by trading with the colonial powers, the break with the capitalist order sparked by the initial slave rebellion in Saint-Domingue dissipated into the air.

Still, even though his rule was full of the kinds of contradictions facing every modern state, paradoxically, the end of the Christophean era would lead to a Haiti that was far less free than the one King Henry left behind. No one knows how things might have turned out had Christophe lived, but we do know how things turned out without him. Christophe was adamantly against paying any reparations to the French. And his death opened the door for France to extort Haiti for millions as the price of the very liberty that the Haitian people had already spilled so much of their blood to secure.