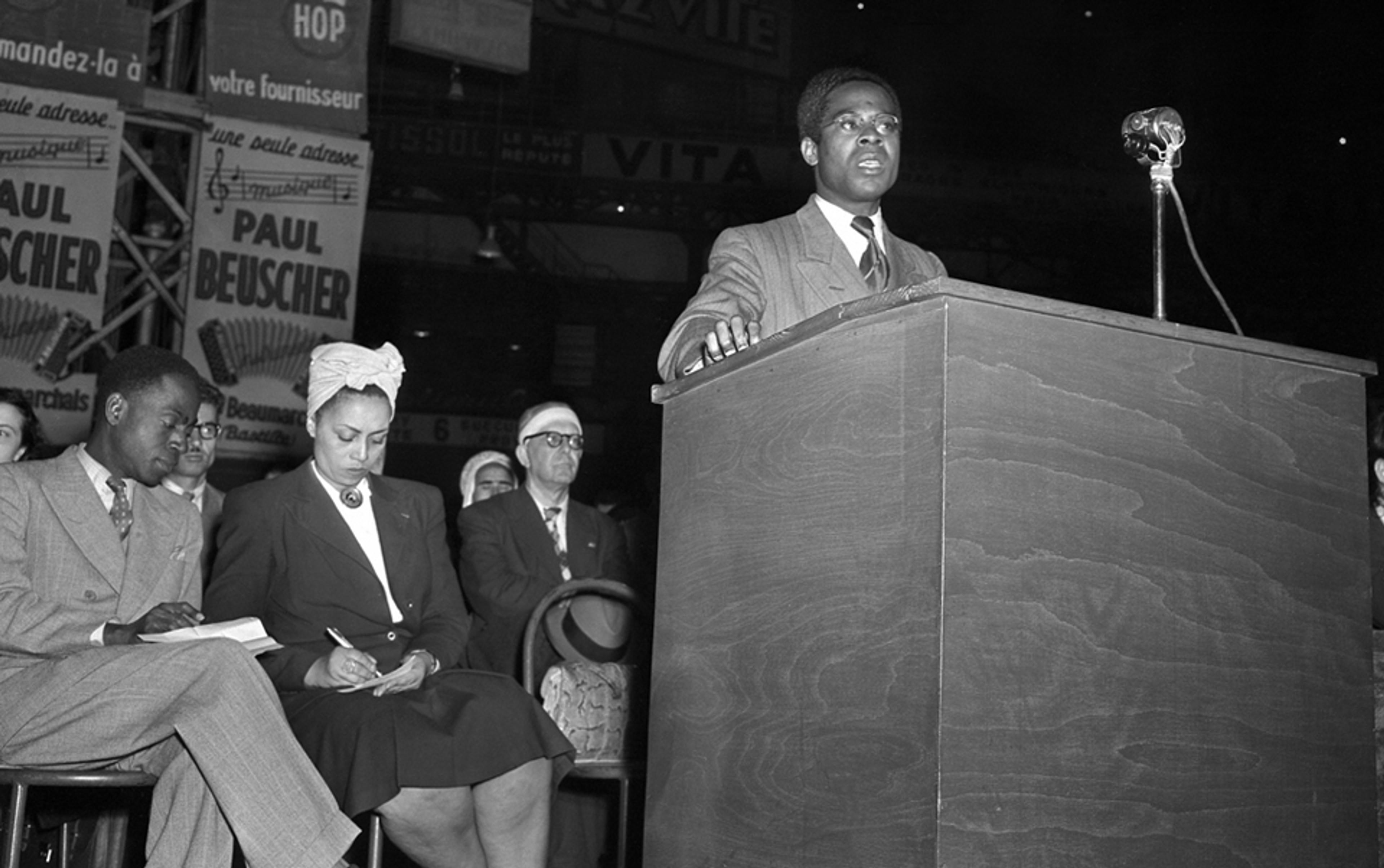

In October 1945, the United Nations began its official existence when the five permanent members of the new Security Council and a majority of other signatories ratified the Charter. That same month, Aimé Césaire, from colonial Martinique, and Léopold Sédar Senghor, from colonial Senegal, were elected as deputies to a new Constitutive Assembly in Paris. This Assembly would draft France’s constitution for a Fourth Republic, following the country’s wartime occupation by Germany and the Vichy state’s collaboration with the Nazi regime.

In January 1946, the first session of the UN General Assembly (GA) convened in London. Its inaugural agenda included a set of global issues: the discovery of atomic energy; the extradition and punishment of war criminals; the problem of refugees and displaced peoples; genocide; the establishment of an International Court of Justice; economic reconstruction projects for member countries devastated by the war; armament regulation; the drafting of an international declaration on fundamental human rights and freedoms; and the creation of a future World Health Organization. In brief, it undertook to outline the shape of the post‑war world.

The first GA also responded to immediate challenges, including a world food shortage; the need for an international children’s emergency fund; the political rights of women; the treatment of Indians in South Africa; the future status of South‑West Africa; and the situation in Palestine. Beneath many of these problems lay the matter of decolonisation. The GA created a Trusteeship Council to oversee the administration of colonised – or ‘non‑self‑governing’ – peoples, whose ‘wellbeing’ and ‘self-government’ the UN charter had pledged to promote. Césaire and Senghor were taking a different approach. These anti-colonial visionaries did not regard nation-states as the best framework through which to pursue justice and equality for Caribbean and African peoples at that time.

In March 1946, Césaire sponsored a historic law that would officially transform France’s so‑called ‘old’ Caribbean and Indian Ocean colonies (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guyane, and Réunion) into full departments of the French nation-state. That same month, Senghor led a vigorous debate in the Paris Assembly on a constitution that would transform the unitary French republic into a post‑imperial and post‑national federation. This new polity would include former colonies and the former metropole as freely associated members, each of which would be self-governing and fully equal federal partners with shared access to the social and economic resources of the whole.

Over the next 10 years, millions of colonised peoples in Asia, Africa and the Middle East won political independence. Overwhelmingly, anti-colonial movements (moderate or revolutionary, liberal or socialist) throughout the world sought to emancipate themselves from colonial rule by creating independent nation-states. European powers shared a preference for seeing their former colonies reinvented as nation-states. When France and Britain recognised that they could no longer retain their colonial empires, they sought to retain imperial influence with former colonies by negotiating bilateral agreements with new, relatively weak nation-states led by political moderates. The United States pursued a similar strategy toward new Third World nations, cultivating non-communist allies, natural resources, and markets among nominally sovereign national states.

The US and Europe thus supported the UN’s view of the world. In this view, the world would be a stable interstate system, organised around the principles of territorial integrity, national independence, and state sovereignty, protected through a directorate of great powers (the Security Council) and administered by a series of international agencies staffed by experts. Human rights violations would merit overriding national sovereignty. But the aim, in such cases, was to protect the inter-state system. Césaire and Senghor wanted something very different. Their vision challenged the very principles of territoriality, nationality and state sovereignty.

During this same period, Césaire and Senghor waged a constitutional struggle to transform the French empire into a transcontinental, democratic and socialist federation. When, in 1956, Césaire concluded that departmentalisation was a mistake, he resigned from the French Communist Party, founded an autonomous party in Martinique, and joined forces with Senghor’s independent socialist party in the National Assembly. Their aim was not only to abolish colonialism but, at the same time, to overcome the traditional notion of sovereign and unified national states. They hoped to invent a new political form for a different world order.

From the perspective of power politics, Césaire and Senghor’s projects might be regarded as utopian schemes with little hope of being realised, out of sync as they were with the nationalist direction in which history seemed to be moving. They were not revolutionary nationalists, and revolutionary nationalism carried the day. Their untimely belief that decolonisation might not require national independence and that self-determination might not require state sovereignty helps to explain why Césaire and Senghor are neglected figures.

But from the present vantage point, their visions seem more pertinent than ever. Since the end of the Cold War, the limits of state sovereignty and the failures of internationalism have become more evident. Private economic actors, unaccountable international agencies, and technocratic experts have superseded state and democratic sovereignties. The failed promises of national self-determination and universal human rights are underscored by Fortress Europe’s handling of the Mediterranean refugee crisis, or the Greek debt crisis. The bankruptcy of international law is revealed by the Israeli occupation of Palestine and Russia’s annexation of Eastern Ukraine, not to mention the new forms of US imperialism that are legitimised through UN‑sanctioned policies regarding human rights, humanitarianism, and the ‘responsibility to protect’. The absence of a vital framework for internationalist solidarity is clear given the left’s inability to effectively challenge Islamic State’s assaults on Syrian Kurds.

Such examples indicate the need for new forms of anti-imperial internationalism whose aim is not to protect a violent and hierarchical interstate order, but to promote social justice on a world-wide scale, without the intercession of instrumental national states and unaccountable international agencies, through new approaches to coexistence, reciprocity, and human flourishing. The task of reconciling local autonomy and human solidarity, of linking democratic self-management to planetary politics, has never been more vexing.

In short, the recent unravelling of the post‑war order has revealed that there is no necessary relation between either state-sovereignty and self-determination, or between being human and possessing human rights. Under such conditions, human freedom has become a global problem for which there is no self-evident institutional solution. This is precisely the insight that motivated Césaire and Senghor’s seemingly untimely and unrealistic programmes for a different type of decolonisation that could form the basis of an alternative global order.

Between 1945 and 1960, Césaire and Senghor pursued their projects as public intellectuals, party leaders in their respective territories, and deputies in the French National Assembly. Their political interventions proceeded from a belief that late imperialism, by establishing deep relations of interdependence between seemingly disparate peoples and places, had created conditions for new types of non-national political association. They believed that imperialism itself had created pathways to a post-national form of democracy.

Césaire and Senghor hoped to end colonialism without falling into what each regarded as the trap of a hollow national independence, a national independence without political agency. Instead, they hoped to build a legal and political framework that would recognise the entangled history that bound metropolitan and overseas peoples to one another. They wanted to protect Caribbean and African peoples’ economic and political claims on a French society whose wealth their resources and labour had helped to create. Rather than allow France and its former colonies to be separated, relating to one another as foreigners, Césaire and Senghor sought to reinvent the long-standing relation of interdependence. Interdependence between metropole and former colony, they rightly saw, was the future as well as the past.

To this end, they pursued a constitutional struggle in the National Assembly to transform the French republican empire into a decentralised federation that would abolish colonialism and revolutionise existing forms of republicanism. Socialist and democratic, transcontinental and multinational, this new type of state would include former colonies as freely associated and self-governing members. Each would possess a local territorial assembly and an autonomous administration through which to manage its own affairs.

They would also send representatives to a federal parliament. Metropolitan France, Senghor explained, would become ‘one state among others, no longer the federator, but the federated’. Overseas peoples would be self-governing and subject to their own civil law even as they also enjoyed full French citizenship, juridical equality within the federation, and socioeconomic solidarity with the rest of France. Former colonial subjects, in Césaire and Senghor’s plan, would also be charter members of the emergent European Community. Césaire and Senghor were not simply demanding that overseas peoples be fully integrated within the existing national state: they were proposing a type of revolutionary integration that would reconstitute France itself, by quietly exploding the nation-state from within.

Rather than demand decolonisation for Martinique or Senegal, they called on Caribbeans and Africans to decolonise France

Césaire and Senghor believed that political independence could never ensure true decolonisation. Martinique and Senegal were simply too intertwined with powerful metropolitan France. True decolonisation would require that the whole empire, metropolitan and overseas, be changed and remade into a different kind of political formation. They thus attempted to seize the historic moment following the post‑war liberation of France and before the beginning of the Cold War, to end colonialism and fashion a new type of self-determination without state sovereignty. In effect, Césaire and Senghor called on the revolutionary ideals of France to recognise and accept responsibility for the world that its own imperial history had created.

This project to transform France from within was at once gradualist and revolutionary, instrumental and ethical, pragmatic and utopian. Rather than simply demand decolonisation for Martinique or Senegal, they called on Caribbeans and Africans to decolonise France. They did not simply want to replace colonial rule with separate national states. They wanted to invent a new type of democracy within which multiple peoples, civilisations and legal orders would coexist. They believed that such a transcontinental polity would ensure autonomous self-government, democratic socialism and cultural integrity, while also creating a different framework for international justice.

Rather than approach the French state as foreigners asking for charity, Caribbeans and Africans would be able to claim development and social welfare resources as citizens of an autonomous region. Rather than depend on the good will of international agencies to redress harms, they could prosecute claims in a federal justice system. This post‑national federation, they hoped, would allow them to hold European imperial powers accountable for past injuries. It would also provide a check against ongoing forms of exploitation and serve to protect them against future forms of imperial domination. Such a transcontinental and multinational state, they believed, could also serve as a model and building block for a new global order that might allow humanity to pursue the dreams of solidarity and reciprocity proclaimed by different currents of post‑war internationalism. In short, they did not regard decolonisation only as the means to secure political autonomy or improve living conditions; they regarded it as an opportunity and responsibility to remake the world.

Of course, Senghor and Césaire’s programme for post‑national democracy was never realised. Even among revolutionary anti-colonials, most believed that self-determination required state sovereignty for independent nations. Even if Césaire and Senghor had convinced the French state to effectively negate itself by joining their post‑national, democratic-socialist federation, it is likely that such an arrangement would have created all manner of problems. Moreover, historical conditions have shifted dramatically since the late 1940s. So why should Senghor and Césaire’s propositions merit attention?

Césaire and Senghor warned against precisely a global politics taking place in an international arena of competing nationalisms, promoted in the post‑war period by Europe, the US, the UN, and most post‑colonial states. Given the interdependent character of 20th-century European imperialism, global capitalism, social mobility and cultural mixing, Césaire and Senghor believed that the coming nationalist internationalism would merely allow powerful, territorial states to continue to dominate. Nominally independent post‑colonial nation-states would find genuine economic development, democratic socialism and international standing elusive, even impossible, goals.

Césaire and Senghor hoped to transform the world order into one of post‑national democracies, organised around intercontinental federations. These new formations would accommodate legal pluralism and cultural coexistence. Self-government would be reconciled with economic solidarity, rights of work and mobility, political citizenship, and mechanisms for justice on supranational scales. Through them, the false choice between, on the one hand, sovereign national states and, on the other, either an unaccountable world state or set of international agencies would be avoided. Their initiatives were based on the conviction that, in the mid-20th century, it would be impossible for colonised peoples to effectively de-link from the larger economic system and geopolitical forces that would continue to bind them to new and former imperial powers. They thus concluded that a decolonisation that did not also seek to transform metropolitan societies, invent political frameworks that could democratise these inevitable linkages, and rethink political relations on a larger scale would fail to achieve advancement and substantive freedom for colonised peoples.

In their attempts as political actors and intellectuals to secure a more novel and thorough decolonisation, Césaire and Senghor developed a pragmatic and experimental relationship to politics. Their point was not simply to champion federalism and reject nationalism; rather, it was to recognise that the prospect of colonial emancipation posed a set of genuine problems for which there was no all-purpose solution.

Césaire and Senghor proceeded as if vital pasts and possible futures all lay before them in a dynamic present

Rather than presume that decolonisation required national sovereignty, they tried to envision a political framework that would enable their people at that historical moment to enjoy the types of substantive autonomy, self-management, un-alienated social relations and human development promised by the concept of self-determination. They wanted people to see that self-determination became tied to state sovereignty through a historical process, but that there is no necessary relation between them. Their efforts serve as reminders that seemingly equivalent terms – freedom, emancipation, liberty, independence, sovereignty, autonomy, self-determination – need to be distinguished from one another.

Césaire and Senghor exhibited an extraordinary ability to think about political and historical possibilities. The fact that their intercontinental federations were a course not taken should not blind us to their possibilities. Césaire and Senghor spent their lives challenging conventional assumptions about possibility and impossibility, realism and utopianism, failure and success, pragmatism and principles. They combined close attention to the best possible prospect in a given situation with acts of political imagination and utopian vision that anticipated worlds to come. Despite their remarkable sensitivity to possible choices in the present moment, they always also took the long view – both backwards and forwards – in matters concerning colonial emancipation, social improvement, and human reconciliation.

Refusing to accept the conventional assumption that self-determination required state sovereignty, their programme for decolonisation proceeded from the belief that African and Caribbean peoples could not presume to know a priori which political arrangements would best allow them to pursue substantive freedom in the post‑war world. Yet this pragmatic orientation was paired with a utopian commitment to anticipatory politics through which they hoped to transform France and the world. Indeed, to do so, they had envisioned a future, in part, by looking into past unrealised and seemingly outmoded emancipatory projects. Césaire and Senghor proceeded as if vital pasts and possible futures all lay before them in a dynamic present.

Given the inability of the existing nationalist internationalism to adequately address pressing global political challenges, Césaire and Senghor seem like visionaries. The toxic fiction of civilisational incommensurability shared by Western xenophobia and political Islam, in addition to the global war on terrorism, and the ways that struggles against Western imperialism became a form of imperialist anti-Westernism all illustrate the enduring iniquity and ongoing impossibility of de-linking between the West and its former colonies.

Consider also the punitive treatment, led by the European Union and the international financial community, of Greece trying to resist the authoritarian dictates of global finance through a popular left government. It seems proof of the EU’s disastrous decision to constitute itself as a technocratic confederation of states rather than as a truly democratic federation led by a continental association of self-governing peoples for whom resources were shared, risk was socialised, and autonomy was meaningful. Senghor and Césaire’s road not taken may still lay before us.