If you’ve tried to open Pornhub in the United States recently (and no judgment if you have), there’s a reasonable chance that, instead of a cornucopia of explicit sex, your browser showed a paragraph of white text against a black background, informing you that the site was unavailable. That’s because, as of this January, 19 states – Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Utah and Virginia – have laws requiring age verification for adult online content. Pornhub put up a firewall rather than comply. If nothing else, the move increased traffic to VPN (virtual private network) services, which provide users with unfettered access to Pornhub regardless of their location by securely connecting to a remote server. The given reason for requiring age verification – that pornography harms the minors who view it – is the latest salvo in a centuries-old American debate over erotica.

These state-level conflicts in the US emerged amid an international push for age verification on adult sites. In 2014, Mexico enacted an age verification law. The European Union’s Digital Services Act (DSA), passed late in 2022, imposed several restrictions on Pornhub and other large pornography sites, including age-verification requirements. A similar measure in Britain, the 2023 Online Safety Act, took effect in January 2025. France, which already required age verification in an earlier law, recently blocked four pornographic sites (Pornhub was not among them) from operating within its borders after finding that the sites failed to check users’ ages adequately. Members of the Canadian House of Commons continue to debate the Protecting Young Persons from Exposure to Pornography Act, which would require age verification. There, as elsewhere, civil libertarians warn that these laws fail to define ‘sexually explicit material’, and raise serious privacy concerns. Pornhub is challenging the laws on multiple fronts.

Efforts to curb minors’ access to sexually explicit online content tend to skip over the precise contours of who or what is at risk in a world without such measures. Supporters generally justify these laws as attempts to protect children from inappropriate content. Some of the laws (such as the DSA in Europe) contain provisions to protect minors from nonconsensual and exploitative participation in adult content. It is not always clear, however, if the ‘harms’ they refer to are those inflicted on sexually abused children whose trauma is recorded and uploaded to pornography sites, or those of the minor who views online consensual sex between adults. By adding age-verification requirements to laws that seek to end child pornography, governments suggest that to look at explicit sex is to suffer abuse.

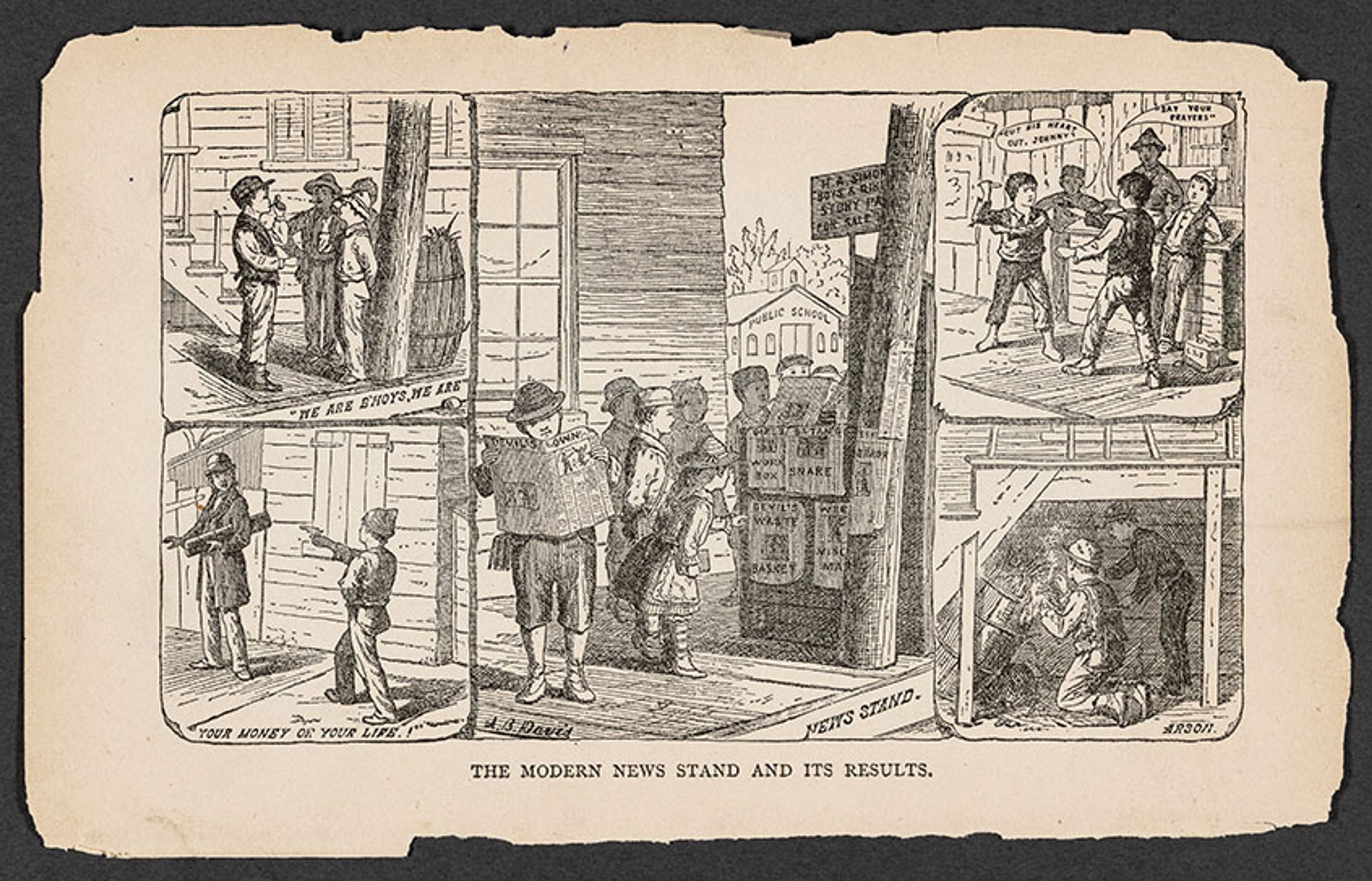

Page from Traps for the Young (1883) by Anthony Comstock. Courtesy NYPL digital

Americans have been especially prone to arguing that looking at pornography is as harmful as being forced to participate in it or subjected to sexual violence. More than a century ago, the anti-vice crusader Anthony Comstock alleged in his book Traps for the Young (1883) that ‘evil reading’ was like a contagious disease, infecting young people (especially, he feared, boys). ‘Our youth are in danger,’ he warned, ‘mentally and morally.’ Comstock lamented the prurient plots of crime novels, but he really got going when he described ‘death-traps by mail’ – his overheated euphemism for mail-order erotica. Young men, he warned, would read smut, then rape and murder young women:

There are in a neighbouring city, at this writing, three youths on trial for murder. It is charged that after a most monstrous conspiracy, a young and beautiful maiden was ruined and then murdered to hide their shame. Lust has but to whistle, and red-handed murder quickly responds, obedient to his master.

Parents should worry that even exposure to a ‘foul-minded nurse’ could infect their daughters with the ‘curse and blight’ of obscenity – these daughters would likely end up in a brothel, he warned. In Comstock’s breathless prose, erotica became not simply an enticement to sin but a threat to life itself.

Comstock was a buffoon, and many of his contemporaries found him repellent. But he was also enormously influential. He convinced Congress to pass a vast anti-obscenity measure in 1873 that empowered him to seize all items he personally found vile, including anything related to contraception or abortion. And, as I write in my recent book Fierce Desires: A New History of Sex and Sexuality in America (2024), he reshaped how Americans understood pornography’s harms. His contention that pornography could turn horny boys into murderers and good girls into prostitutes endured long after legal challenges overturned most of the 1873 law. Since the 1870s, the idea of whom porn harms has varied – boys, young men, all women, or society at large. But this association between erotica and injury continued to inspire generations of policymakers and activists.

Proposals to limit porn access in the name of protecting the innocent are as misguided today as they were in 1873. I say this despite my ethical concerns about Pornhub and its corporate parent MindGeek (now rebranded as Aylo). These entities seldom removed videos depicting child abuse, rape or sex trafficking until an investigation by The New York Times in December 2020, alleging years of exploitative content, led Mastercard and Visa to block use of their cards to process payments on the site. In August 2022, Visa and Mastercard also suspended payments for advertisements on MindGeek after a woman sued Visa for helping monetise depictions of child pornography. Notably, the credit card companies acted in response to harms inflicted on the individuals involved in the creation of adult content. What Comstock argued – and what is resurfacing in conservative age-requirement legislation – is the idea that pornography injures those who see it. This understanding of explicit sexual content as assaultive has very little to do with actual physical or emotional damage. It instead reveals attempts to regulate sexuality, always with a heterosexual (and, often, marital) norm in mind.

Jonathan Edwards by Henry Augustus Loop, after Joseph Badger, 1860. Courtesy Wikipedia

The idea that erotica injures those who consume it has competed with an older criticism of pornography as simply unseemly. In 1744, the esteemed Massachusetts minister Jonathan Edwards investigated rumours of ‘lascivious and obscene discourse among the young people’. Adolescent boys and young men in his congregation had read two popular medical texts, from which they learned about female sexual anatomy, orgasm and the danger of ‘greensickness’, an illness one book described as the consequence of abstinence. The youths then teased girls in the community about ‘what nasty creatures they was’. When Edwards attempted to rid his congregation of ‘bad books’, many members of his community sided with the boys: what they did in private, it was argued, was of no concern to the minister. For Edwards and many Christians, sexually explicit material was a problem because it violated social norms and might tempt those who encountered it to commit the sin of masturbation. But, importantly, Edwards and his contemporaries understood these sins as self-inflicted, the failures of people of faith to maintain their sexual purity. Erotica was not the assailant; it was the catnip that led the sinner to debase him- or herself. This assessment of pornography as prurient smut endured and influenced later Supreme Court decisions that found certain sexual material violated ‘community standards’ and was ‘without redeeming social value’.

Americans in search of a visual thrill soon did not have to rely only on midwifery texts. The most popular erotic text in the Anglo-American world for a century, Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, was published in England in 1748, translated into French and Italian, and printed stateside as early as the 1780s. Fanny Hill told the improbable story of a sexual naïf who found herself, at 15, living in a brothel and thoroughly enjoying the erotic adventures it offered, each male ‘member’ she encountered more delightful and thrilling than the last. Fanny Hill was one of a few books of its kind in the 1700s, but, by the early 19th century, it circulated within an expansive world of commercial sex in cities from Boston and New York to Baltimore and New Orleans. Affordable prints and texts traversed the nation’s canals and nascent railroad lines, packed into the bags of men heading to Texas and California in the hope of claiming land, fighting Indians, or discovering gold. In 1852, when a traveller named Richard Hickman came upon piles of personal possessions abandoned by men who had travelled the Platte River before him, he found ‘books of every sort and size from Fanny Hill to the Bible’. These images and texts were one part of an expansive sex-based consumer culture in the US. Bookstores sold drawings of female nudes and stories of explicit sexual acts, some grocers allowed sex workers to solicit clients for assignations in adjacent rooms, and boarding houses often doubled as brothels.

Much of the cultural uproar over ‘juvenile delinquency’ barely concealed the era’s tense homophobia

By the time a young Anthony Comstock joined the Union Army in 1863, pornography was everywhere in American print culture. Comstock, raised as a devout Protestant, was outraged to discover its ubiquity. He spent the ensuing months idly stationed in a Florida encampment with hundreds of young men who passed the time in part by poring over pornographic images and texts. Nudes on baseball-card-sized cartes de visite, stereoscopes with three-dimensional images of sex acts, and raunchy storytelling around the campfire all disgusted Comstock. When he moved to New York City after the war, he discovered that the nation’s capital of capitalism was the centre for sexual commerce, too. After attempting to raid the stockrooms of booksellers and druggists as a solo agent of his own moral crusade, he enlisted support from the men who led the city’s YMCA. They funded his campaign to convince Congress to legislate his religiously based view of sexual morality.

Over the next 50 years, Comstock reigned supreme as America’s anti-vice evangelist and investigator-in-chief. His commitment to purging American life of the devil’s handmaidens never wavered. He considered anyone who sold erotica, taught about contraception, or circulated anatomically precise sex-education materials equally complicit in the moral impairment of generations of youth.

A booth of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in Temescal Canyon, California in 1922. Courtesy Santa Monica Public Library

His argument that sexually explicit materials harmed youth took hold. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, members of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union opened ‘purity libraries’ free of any books that might tempt young people to sin. Yet this push for censorship competed with popular demand for erotic content. American popular culture grew increasingly sexualised in the 1920s, from the bathing beauties of the new Miss America pageant in Atlantic City to raunchy pre-Hays Code cinema. By the 1940s, coy body cream advertisements promised romantic rewards for tender skin.

This growing acceptance of intentionally suggestive images of women’s bodies coincided with a fixation on two variations of male sexual deviance: sadism and homosexuality. The psychiatrist Fredric Wertham gave voice to these concerns in his bestselling exposé, Seduction of the Innocent (1954), about the danger comic books posed to youth and the related need to keep violent material out of children’s hands. Much of the cultural uproar over ‘juvenile delinquency’ barely concealed the era’s tense homophobia. Congress held hearings about the possibility of coded inducements to male homosexuality within comic books, while public health campaigns warned boys as well as girls to be suspicious of male strangers who wanted to make their acquaintance. Conservative organisations such as Citizens for Decent Literature (CDL), a Cincinnati-based anti-pornography organisation led by Charles Keating (a Catholic inheritor of Comstock’s Protestant mission) created an anti-porn roadshow, the incongruous centrepiece of which was a detailed presentation of contemporary porn, ostensibly for the sake of illuminating the filth that youth might access. The CDL linked exposure to pornography with violent crime, juvenile delinquency and ‘perversions’, especially homosexuality. The CDL also amplified warnings that men who consumed erotica became sexually abusive. False conflations between pornography (of any kind) and violent or ‘deviant’ behaviour persisted. The president Lyndon B Johnson appointed a Presidential Commission on Obscenity and Pornography in 1967 to study the association between pornography exposure and violent behaviour. The social scientists who dominated the commission instead wrote, in their final report in 1970, that the real danger was men’s exposure to violence, not to sex.

American interest in regulating pornography was anything but clear by the mid-20th century. The Supreme Court case Roth v United States (1957) defined obscenity as whether ‘to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appeals to prurient interest’. The Roth test created a First Amendment protection for speech that could be interpreted as expressing ‘even the slightest redeeming social importance’, but it also offered censors a basis for restricting sexually explicit films, magazines and books as violations of community standards. Even as American culture and US law grew significantly more tolerant of explicit sexual material, the legal system continued to single out ‘perverse’ forms of sexual expression, particularly anything relating to homosexuality, for harsher restrictions. Citizen groups and municipal zoning commissions did what law enforcement could not to impose limits on pornography in their communities. Communities limited where adult theatres and bookstores could operate, stifling businesses. Gay erotica remained more likely to be censored than straight material. The Los Angeles Police Department, for example, continued to raid gay bookstores and theatres into the mid-1970s, seemingly content to harass business owners and customers even as the chances for convictions dwindled.

A profusion of nudity and sex (implied or explicit) in books, advertisements, magazines, films and plays brought a vocal minority of Americans to a fever pitch of outrage, but it failed to alarm the masses. Even when the Supreme Court ruled in Miller v California (1973) and Paris Adult Theatre I v Slaton (1973) that the government could restrict sexual speech and performance for the sake of maintaining ‘a decent society’, the result was not a return to Comstockian censorship. ‘Community standards’ were changing rapidly. Most local and state governments saw little point in committing law enforcement resources to prosecuting pornographers.

The American conversation about pornography and harm took a significant turn in the 1970s as new voices warned that it endangered the lives of women. Anti-porn activists addressed the dangers facing not only the women who performed in adult films but women generally, as a disadvantaged class. Jonathan Edwards had scolded his congregation in the 1750s that pornography insulted women; a new anti-porn movement asserted that images of abuse in pornography and in advertising provoked men to acts of physical violence. (Even when Wertham warned about the violent tendencies of porn-addled juvenile delinquents, he worried far more about how comics corrupted the minds of boys than about the victims of their alleged aggressions.) This shift occurred because new feminist groups emerged to protest what they considered damaging and dangerous images of abuse in pornography and in advertising. The 1976 film Snuff, which purported to capture a woman’s rape, murder and dismemberment, mobilised feminists in Los Angeles to form a new organisation, Women Against Violence Against Women. The group successfully campaigned for the removal of a billboard for the Rolling Stones’ new album, Black and Blue (1976), which showed a woman in torn clothing, her hands bound above her head, legs parted, and her neck and limbs seemingly covered in bruises. The text on the billboard read: ‘I’m “Black and Blue” from The Rolling Stones and I love it!’ West Coast feminists launched boycotts of record companies to demand that they remove images of violence against women from their album covers.

Debates over the links between pornography and harm became referenda on sexual freedom. In the early 1980s, the feminists who founded Women Against Pornography (WAP) teamed up with religious conservatives to support local bans on pornography. Sex-positive feminists, adult-film actors, and gay/queer liberationists countered that anti-gay government censorship and police aggression against sex workers were the greater dangers. In 1985, the attorney general Edwin Meese announced a new Commission on Pornography. Deeply socially conservative, Meese filled the commission with evangelical Protestants and others already convinced that pornography turned porn-obsessed men into violent abusers. WAP provided the commission with a list of potential witnesses, many of whom were women who testified at federal hearings that they had endured sexual, emotional and physical abuse from husbands ‘addicted’ to pornography.

The commission’s 1,960-page final report, published in 1986, concluded unequivocally that pornography caused violence against women. In Chicago, an ex-Playboy bunny named Brenda MacKillop synthesised the conservative religious argument against pornography:

I emplore [sic] the … commission to see the connection between sexual promiscuity, venereal disease, abortion, divorce, homosexuality, sexual abuse of children, suicide, drug abuse, rape and prostitution and pornography and its philosophy that permeates our society.

Efforts to outlaw pornography created strange bedfellows among religious conservatives and anti-porn feminists. In the 1980s, the liberal attorney Catharine MacKinnon pursued her (unsuccessful) efforts to have cities ban explicit content because ‘exposure to pornography increases normal men’s willingness to aggress against women’. Importantly, WAP and its supporters in government did not distinguish between violent and non-violent pornography; regardless of the sex portrayed on screen, it was, by definition, incitement to harm.

These critiques gloss over the distinctions between consent and coercion, or between abuse and pleasure

This view persisted on the political Right for decades, although the Republican Party seemed to forget its concerns about women’s safety. With the expansion of the internet in the 1990s, the Republicans’ attention shifted to the harm that online pornography inflicted on children, either through the exploitation of child pornography or, more amorphously, through their exposure to adult content. Legislation passed under the president George W Bush in the early 2000s linked the problem to international human trafficking. The PROTECT Act of 2003 created the AMBER alert system and authorised federal law enforcement agents to target human traffickers and sex tourists. The 2016 Republican platform made the connection in clear terms:

Pornography, with its harmful effects, especially on children, has become a public health crisis that is destroying the lives of millions. We encourage states to continue to fight this public menace and pledge our commitment to children’s safety and wellbeing.

(The Republican Party did not adopt a new platform in 2020, and its 2024 platform does not mention pornography.) The Democratic Party has not addressed adult content in its party platforms.

Sex educators and public-health advocates have lately returned to the topic of pornography’s injurious effects on women. In the 2010s, media outlets and a few social scientists reported that young women were increasingly at risk of nonconsensual choking and anal penetration during heterosexual sex. Porn, they contended, was to blame. The reporter Kate Julian made this association in a 2018 cover article from The Atlantic, citing studies that demonstrate correlation, not causation:

Studies show that, in the absence of high-quality sex education, teen boys look to porn for help understanding sex – anal sex and other acts women can find painful are ubiquitous in mainstream porn.

Christine Emba, a conservative columnist, wrote in her treatise on premarital chastity, Rethinking Sex (2022), as if the link was a forgone conclusion. She explained that men’s pornographic obsessions drove violent behaviour, and that it has prompted some of her female friends (the main source material for her book) to become lesbians. These arguments rest on weak evidence, but a growing data set indicates that boys and young men treat erotic asphyxiation as normal behaviour with female partners. Choking can cause brain damage and even death. Its popularity in online pornography does seem to have inspired a new trend: a mimicry of the violence normalised on screen. On-screen violence, not sex per se, appears to be the culprit.

The arguments of anti-porn feminists from the 1970s and ’80s now feature prominently in socially conservative efforts to restrict adult content. An organisation called Fight the New Drug is dedicated to educating the public about ‘the harmful effects of porn’. Even non-violent pornography, they argue (as WAP did), can instigate abuse: ‘Study after study has found that even consuming “regular”, non-violent porn is connected with the consumer being more likely to use verbal coercion, drugs, and alcohol to push women into sex.’ They cite peer-reviewed research indicating that ‘porn consumption is a significant predictor of sexual aggression’ with partners. This research also describes the mental health effects of porn consumption, of being partnered with someone who consumes it, and of ‘revenge porn’, when a former partner shares intimate content online.

Fight the New Drug claims to have indisputable proof that pornography causes violence, but that is hardly the case. Much of the research it references is focused on individuals who are addicted to pornography and consume it compulsively; their brains reveal changes similar to those of people with alcohol and drug addiction. Fight the New Drug also falsely asserts that ‘an analysis of 33 different studies found that exposure to non-violent porn measurably increased aggressive behaviour, and consuming violent porn increased even further,’ but the study they cite discusses just 22 prior studies and reached a far more ambiguous conclusion. Nor did the study draw any conclusions about violent behaviour. Rather, the analysis found some correlation between the amount of pornography men consumed and their acceptance of the ‘rape myth’ (the definition for which includes the belief that women who wear tight skirts are ‘asking for it’, and that many women subconsciously want to be raped). That finding is hardly conclusive. The authors conceded that, given ‘the inability of the analysis to isolate a causal relationship among variables’, their results do not ‘inherently mandate or specify any action’.

Younger Americans today seem to turn to pornography not only for erotic stimulation but to learn about sex. A report on pornography consumption published in 2023 revealed not only that 73 per cent of the study’s respondents, aged 13 to 17, had viewed online pornography, but that nearly half considered it a ‘helpful’ source of information about sex. The importance of pornography within LGBTQ+ communities further complicates this picture. Some LGBTQ+ consumers of adult content defend pornography as educational, particularly given the decline of comprehensive sex education in public schools. Queer people are especially likely to describe pornography as a key source of sexual knowledge, particularly given the disproportionate representation of straight sex in film and television.

Over and again, American campaigns against pornography stir up moral panic by asserting that explicit sexual content harms the people who view it – children especially. And they make this argument by insisting that there is something about visualising sex that incites violence. It’s an unnuanced and often factually tenuous case that confuses erotica with cruelty. And it diminishes the importance of efforts to protect people from actual sexual harms. Many feminists in the 1970s and ’80s believed that a popular culture saturated with banal representations of the abuse of women created a permission structure for real violence. Too often, these activists argued, Americans made violence against women look sexy. The conservative anti-pornography movement, however, aligned with feminists who took the more extreme position that pornography itself was inherently violent, however consensual the acts portrayed. These critiques gloss over the distinctions between consent and coercion, or between abuse and pleasure. They have led to crackdowns on queer and nonmarital sexuality.

In June 2024, free speech activists and adult content producers in Indiana sued the attorney general Todd Rokita for enacting ‘state censorship’. Like many supporters of age-verification laws, Rokita insists that these laws empower the state to defend young people against injury. ‘Children shouldn’t be able to easily access explicit material that can cause them harm,’ Rokita wrote on X. ‘We need to protect and shield them from the psychological and emotional consequences associated with viewing porn.’ Yet the idea that viewing pornography causes ‘psychological and emotional’ harm is a controversial claim – one far more often stated than proved. A similar suit out of Texas, Free Speech Coalition, Inc. v. Paxton, reached the Supreme Court in January of this year. During oral arguments in which Justice Samuel Alito asked if anyone perused Pornhub ‘for the articles,’ the justices indicated their likelihood to rule against free speech for the sake of child protection, a reversal of established precedent.

Americans need comprehensive information about their sexual health. PornHub is not the ideal place to go for that information (the site has a section dedicated to sex education), but legislation is a crude tool for controlling speech. As legal scholar Mark Joseph Stern notes about the court’s likely support for age verification laws, ‘if the court takes this step, there’s no reason why states’ battles against explicit material must stop at PornHub,’ with online bookstores and streaming services potentially at risk. As in the past, legal permission to restrict sites like PornHub will enable censorship of information about queer sexuality, whether explicit or not. (Indeed, in the mid-1990s, HIV/AIDS activists fought against provisions of the Communications Decency Act that would have forced them to take down HIV-prevention information directed at teens.) Pornography addictions and the consumption of violent media do seem to inspire aggressive and dangerous sexual behaviors. Perhaps we should focus our public health campaigns on those issues. Instead, in a culture saturated with guns, gory video games, and shows depicting gratuitous cruelty, Americans remain far more concerned about sexual content than explicit violence. History shows that any attempt to censor pornography will inevitably also curtail access to the sort of sexual speech that we need today more than ever.